Use the slideshow to view Furmansky's photographs. If viewing on a computer, clicking the image will open the slideshow in a shadow box gallery.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau argues that place comes before space. In the chapter titled “Spatial Stories,” he establishes that place is the order with which things are distributed. Two things can’t be in the same place at the same time: “A place is thus an instantaneous configuration of positions. It implies an indication of stability.” Space, on the other hand, “exists when one takes into consideration vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables.” It occurs as an “effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function.” In a rare moment of clarity, de Certeau offers this equation: “In short, space is a practiced place.”

While the definitions are right, the order feel backwards for Houston. Here, space reigns supreme. The flat coastal plain extends for miles, originally only interrupted by the dips of meandering bayous. On this expanse, Houston appeared as a transactional node. As a center of the oil and gas industry, it has historically made its money through the movement of distant materials. This is seen in the port that dominates southeastern Houston, the logistical hubs that ring the city, and the spread of residential developments that make more sense in a spreadsheet than they do in person. The mobile idea of Houston was sold at a profit long before there was any notable Houston on the ground to speak of. Place is much harder to come by here. There are lots of good places now, but we’re at work on making more and better ones, as Cite 101 explored.

It’s fitting, somehow, that Pennzoil Place has place in its name. Place arrives with a whiff of exclusive urbanity—think Courtlandt Place. It suggests a property for purchase on a Monopoly board. But it’s also the more durable word: While Pennzoil products are still available, Pennzoil itself was acquired in 1999 and is now part of the Royal Dutch Shell conglomerate. Pennzoil Place was developed by Hines, led by Gerald D. Hines, who recently passed away (read Cite’s tribute here), and is now owned by Metropolis Investment Holdings Inc. I hadn’t seen the inside of the building until I began Googling for this text, but it seems to be straightforward Class A space. It’s also about 35% unleased, in case you’re looking for a new office.

The most distinctive part of the building, designed by Johnson/Burgee, is its shape—or, rather, its shapes: Two towers with tapered tops and a connecting atrium. This reading bears out if you’ve been in the lobby and noted how the glass works on either side of the trussed sloping enclosure or how the towers meet the interior “ground.” The story of its design is well-known, with Hines and Philip Johnson scheming it up in close collaboration and, later, Johnson slicing the tops of the towers at opposing angles to satisfy a client’s need for distinctiveness, a hint of starchitectural practice to come. More background information is available in Mark Lamster’s The Man in Glass House.

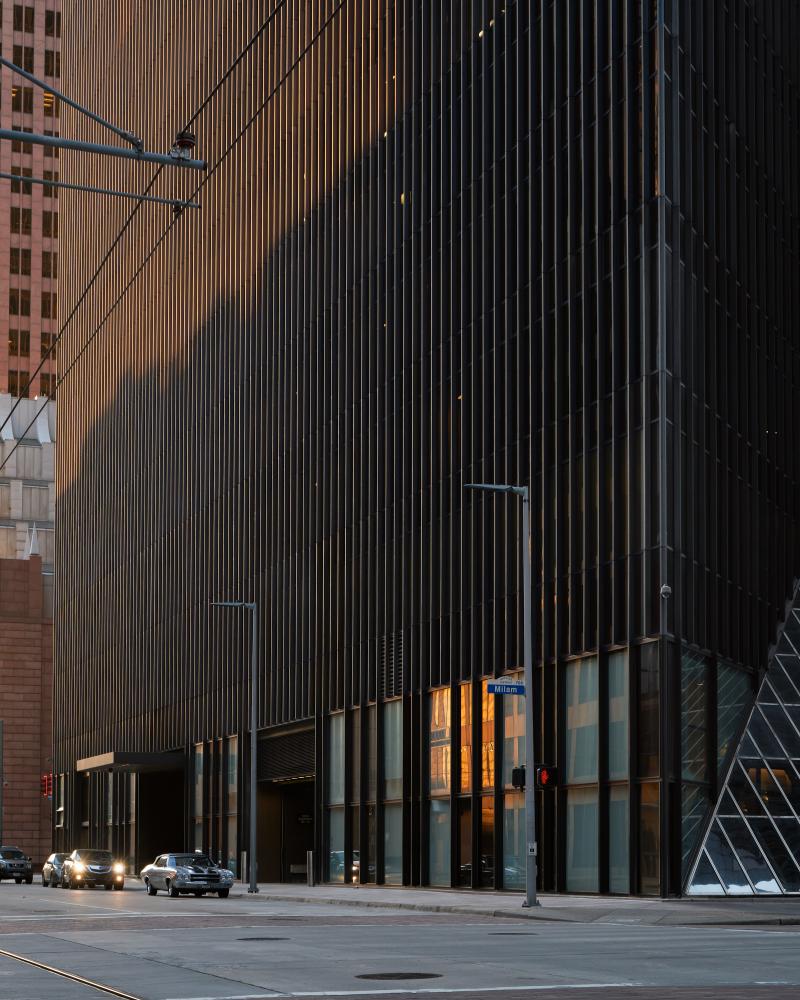

Because of the geometry and its doubling, our twin towers, finished in 1975, appear differently in different places: At times they are a close duo separated by a slit of daylight, but from other vantages they mass together as a single monolith (it’s worth noting that Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was released in 1968 and that Minoru Yamasaki’s World Trade Center was completed in 1973). Pennzoil Place borrows and flattens a dark bronze Miesian façade into something trickier. It even seems to make good on the images that Mies made for a sharp glass skyscraper on Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse in 1921, half a century earlier. Perhaps more than One Shell Plaza and the Galleria (all three developed by Hines), the building “put Houston on the map” in terms of architectural awareness: Ada Louise Huxtable raved about it. Pennzoil Place remains a brooding, iconic cast member in the ensemble of Houston’s downtown skyline.

In a tabloid twist, the twins have a secret third sibling: the Austin National Bank Tower in Austin, also completed in 1975. Hines achieved success through masterful control of construction budgets, to the extent that they operate a Conceptual Construction department that ensures “institutional-quality buildings through a risk-managed process that consistently delivers high-quality development on time and on budget and creates a finished product distinctive in its respective market.” When constructing Pennzoil Place, Hines ordered exterior wall panels in bulk and ended up with enough to clad a new twenty-six-story building that it was developing at 6th and Congress. Its design was carried out by Houston architect S.I. Morris, who also worked on Pennzoil Place. Though handsome, it doesn’t possess the aura of its Houston relative. The tower is currently being renovated by Gensler, but even so its fate will likely remain that of a Late Modern background building—which isn’t that bad, all things considered. When I lived in Austin, the most notable aspect of this building was the P. Terry’s burger stand tucked into one corner of the ground floor, the cheapest downtown lunch available without resorting to non-local fast food chains.

It’s reassuring that buildings, once complete, develop a life of their own, one that's distinct from the conceptualizations of the architect(s) who conceived them. Thankfully, they become places for people. Today, Philip Johnson’s legacy is riddled with serious problems—his active participation in Nazism during the 1930s first and foremost, but also his thirst for fame and his extensive power brokering—but the structures created by his office remain in place across the country. The architecture, separate from the problematic architect, becomes a part of the city and participates in the rhythmic churn of daily life.

But this routine can be interrupted. These evocative photographs by Leonid Furmansky, a Texas-based architectural photographer, offer a portrait of Pennzoil Place as it exists today. They were taken earlier this year during the pandemic. In examining this familiar block anew, we see the streets and sidewalks emptied out save for the lone biker, bus rider, or pair of citizens. The traffic is minimal at best. The glass façade of the building is alternately transparent and glowing from within, or reflective and opaque—or, at dusk, both. We see that Houston is not exactly flat—the ground slopes, as registered in the granite “base” of the building that is tapered into long wedges of stone.

In these images, everything feels deserted. Their stillness reminds us of the troubling, indefinite freeze that the pandemic has placed upon us, but also that not all of us are privileged enough to be working from home. Furmansky’s photographs are a sharp, sober look at place we’ve seen before but now we see it differently. The images are realistic, but they’ve been tweaked into deeper architectural appreciation by the correction of the verticals to be parallel. With this the building appears to process upwards towards the sky, unaffected by perspective.

Furmansky’s work is influenced by contemporary photographers like Bas Princen, whose "Ringroad" image changed architectural photography when it was first seen fifteen years ago (small world: Princen was invited to Houston, where he made "Ringroad," by Lars Lerup, former Dean of Rice Architecture). While the building portrayed in "Ringroad" is an alluring fiction—its scene altered afterwards and, in reality, its mirrored gold glass later replaced with clear blue glazing—Pennzoil Place turned forty-five this year and lives on, largely unchanged. With its anonymous office park nowhereness and highway beyond, "Ringroad" images space in its flows of material, capital, and energy—the things that made Houston famous. But downtown, Furmansky’s images show us Pennzoil Place’s place, albeit in a suspended state. In one image, a table with a white tablecloth is set in a darkened ground floor dining hall, waiting. Come what may, for the foreseeable future this building sits quietly, anticipating the crush of occupants who will, no doubt, return. —Jack Murphy, Cite editor

Leonid Furmansky is a Texas-based architectural photographer. He is driven to document structures that represent the way we live. Leonid's work has been published in the New York Times, Divisare, Texas Architect, Dwell, and ArchDaily. Leonid spends his free time documenting rural and overcrowded cities all while experimenting with film photography.