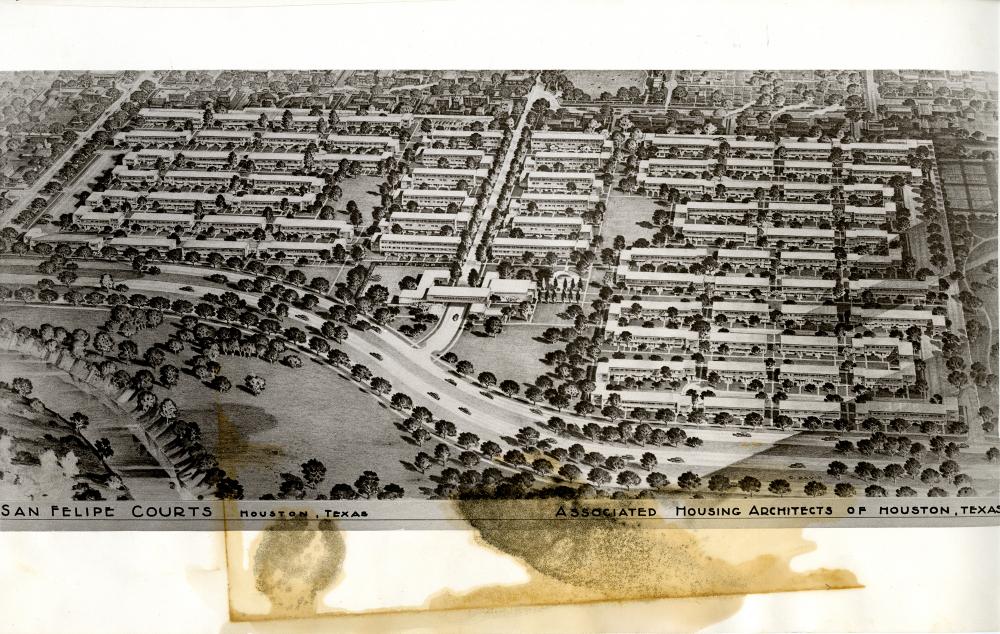

One of the few original drawings of the San Felipe Courts housing development (1939–1942; 1943–1944) depicts a dynamic vision of urban life (Figure 1). The image is kinetic, from the smooth, subtle arc of the Buffalo Bayou Parkway to the repetitious, rhythmic superblocks of San Felipe Courts. The formal features of San Felipe Courts, combined with the stylistic aspects of its rendering, communicate a sense of motion, efficiency, and modernity. The drawing describes not only its architectural subject, but also reveals something of the larger aspirations Houston’s elite held towards modernizing their city. Writing two decades later, architectural critic and historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock tellingly described Houston as “a city that looks to the future, not to the past.” [1]

Yet since its conception San Felipe Courts, later renamed Allen Parkway Village, has been a contentious site between city leaders and residents of the surrounding Fourth Ward. Built between 1939 and 1942 as low-income housing for white residents, the 37-acre project briefly served as defense housing for local workers for the war effort before being opened to a more general population. Since it was integrated, Allen Parkway Village was subsumed into the adjacent Black community, not only providing low-income housing, but eventually becoming a historical and institutional landmark within Houston’s historic Freedman’s Town; by the late 1980s, preservationists and African American residents alike to joined forces to protect the property against demolition and the encroachment of developers. Though the original land parcel still hosts 500 public housing units today, the majority of the original structures were demolished in favor of newer town-home construction.

San Felipe Courts was lauded from the moment of its creation as a modernistic paradigm for the urban neighborhood. [2] Produced by the Associated Housing Architects of Houston under the direction of Karl Kamrath, the project was a thousand-unit complex modeled on reformist design fashions. Like its European predecessors, Kamrath’s design offered a communitarian urban vision, an aesthetic continuation of earlier New Deal efforts at public housing reform. [3] In its later history, the development was the first public housing project in Texas to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. [4]

Yet the apparent merits of San Felipe’s formal and ideological program, especially as seen through the lens of architectural history, fails to account for the project’s controversial role within its historically Black Fourth Ward community. It now seems clear that local officials promoted a foreign architectural style and a blocky massing in an effort to separate the site from the preexisting Fourth Ward community. San Felipe Courts exemplifies what George Lipsitz has called the “spatialization of race,” or what Lawrence Vale has deemed the “design politics” of American public housing. [5] Given its role as a tool for managing Houston’s built, visual, and social worlds, San Felipe Courts also speaks to the phenomenon of “Southern progressivism” and the manner by which a public housing project were co-opted by the city’s larger planning schemes to realize large-scale urban projects meant to improve the city, with only incidental benefits to Houston’s Black and Latino communities.

Although the design of San Felipe Courts has received scholarly mention for its architectural merits, its location in Houston is typically not addressed. [6] The vast majority of literature on American public housing focuses on Northern cities—and not the regional context of a segregated Southern city like Houston. Despite this, the case of San Felipe Courts helps to underscore Lawrence Vale’s argument that the siting of publicly-funded facilities reveals a socially-charged landscape of displacement and difference. [7] American public housing, since its genesis under the New Deal, manifests a protean landscape of rationales—from economic development to social safety net. [8] The placement of San Felipe Courts, paired with its formal design characteristics, speaks to Vale’s notion of “design politics”—the attempt to “reimagine” places through tightly-controlled visual and political messaging. [9] From this perspective, the development was an egregious example of what Jan Lin has observed as Houston’s pervasive history of “ethnic place demolition.” Couched in the language of “slums” and “blight,” the Fourth Ward became the epicenter of “civic improvement” through the aesthetic vocabulary of modernism, an effort that slowly destroyed the historic home of the city’s African American community. [10]

Progressive Styling: The Design of San Felipe Courts

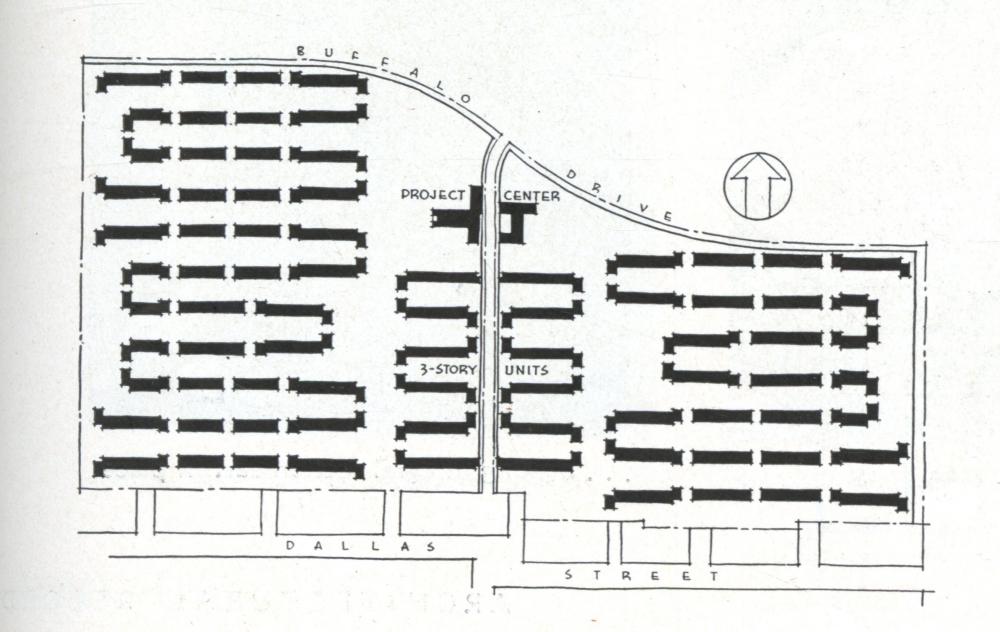

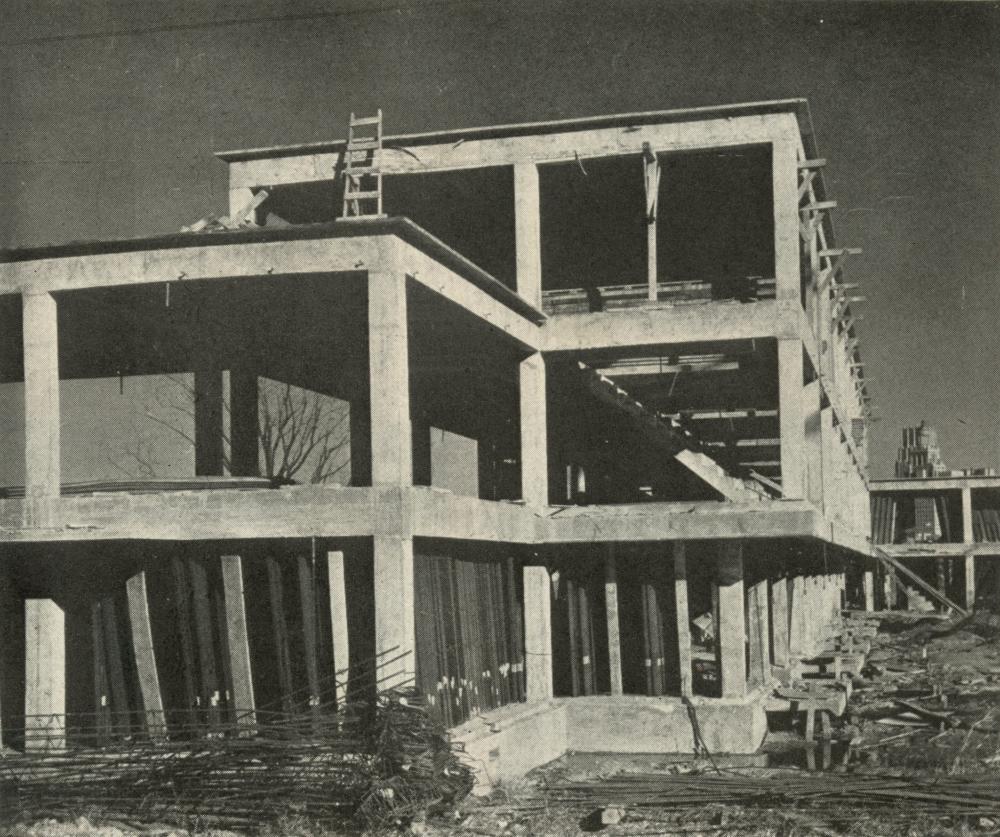

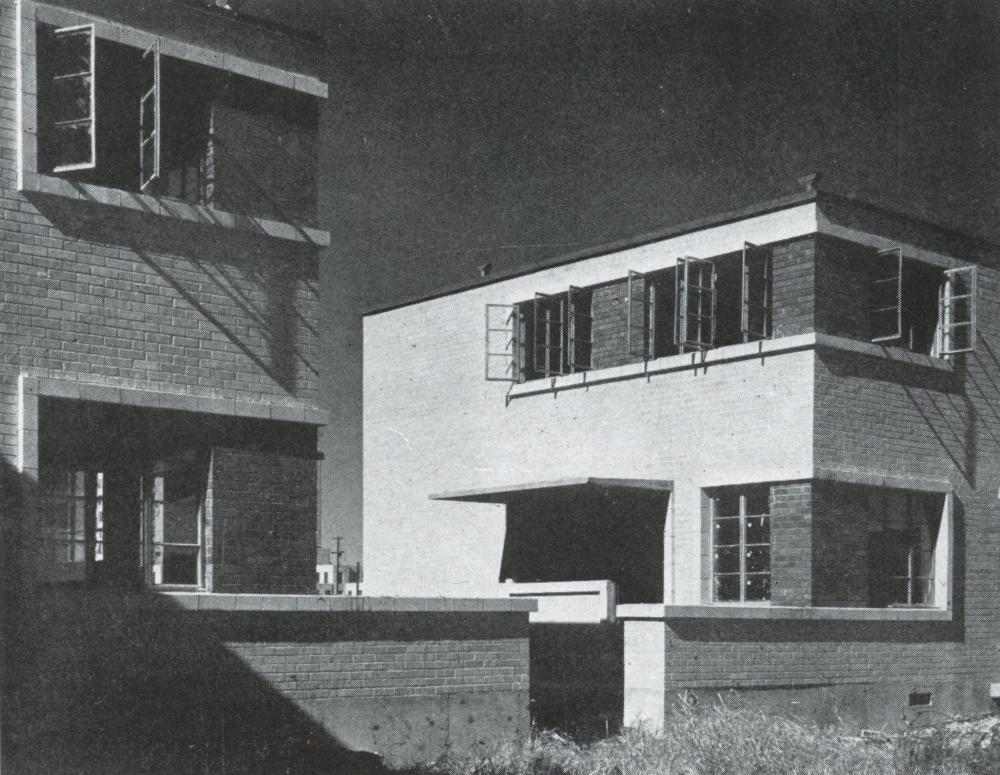

With its rhythmic geometries and its internal disposition of parts, San Felipe Courts is an exemplar of modernist design and a study in community planning. The building complex, which despite its deeply compromised state today, is still operated by the Houston Housing Authority (HHA), originally comprised 1,000 living units, 440 of which occupied a single story, and the remainder of which consisted of two-story apartments. [11] These were spread across eighty individual brick structures arranged within a superblock formation, twelve of which were three stories tall (Figure 2). [12] The three-story units surround Valentine Street, the only vehicular thoroughfare to bisect the development internally, and which features a grand oak tree allée. In a 1942 article about defense housing, the Architectural Record lauded the varying massing heights as they offered “a welcome visual contrast to the monotony of so large an area of buildings of similar height.” [13] Most of the units featured front and back doorways, allowing for cross-ventilation. The superblock structures consisted of flat roofs and a uniform aesthetic palette throughout, while the unit sizes were diverse, ranging from one-bedroom flats to four-bedroom duplexes, thereby accommodating families of various sizes. [14] The rectangular superblocks were built with a reinforced concrete frame and masonry cavity wall infill (Figure 3).

Karl Kamrath (1911–1988), with the assistance of the Associated Housing Architects of Houston (AHAH), was the creative force behind San Felipe Courts. Often compartmentalized as a regional modernist, Kamrath was a noted disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright and one of the designers who most actively disseminated Wright’s vision throughout Texas. Though working within the constrictions of wartime housing, Kamrath succeeded in generating a visually compelling project. San Felipe Courts expresses a minimal interplay of form and color, permeated throughout by a network of pedestrianized interstitial spaces. The buildings are composed of simple forms and lines, giving the project a strong horizontal quality; exteriors feature a kinetic interaction of parallel planes and volumes, all activated in shared motion. The entire development combines a unified vocabulary of forms, materials, and colors. San Felipe’s buildings were faced in blond brick, while the steel casement windows were framed in a creamy white stone. The upper story windows, also banded in white, were interpenetrated along the horizontal axis with deep red brick infills. This same red brick served as a door surround and framing device along first floor entryways. Concrete canopies created a stringcourse between upper and lower stories, providing both shelter and an ornamental device to further underscore the horizontality of the superblocks. In some locations the canopy was brought down to join the floor slab, suggesting a pliable, elastic form. In other places, the canopy extended beyond the building like a fin that visually continues the building’s dynamic motion.

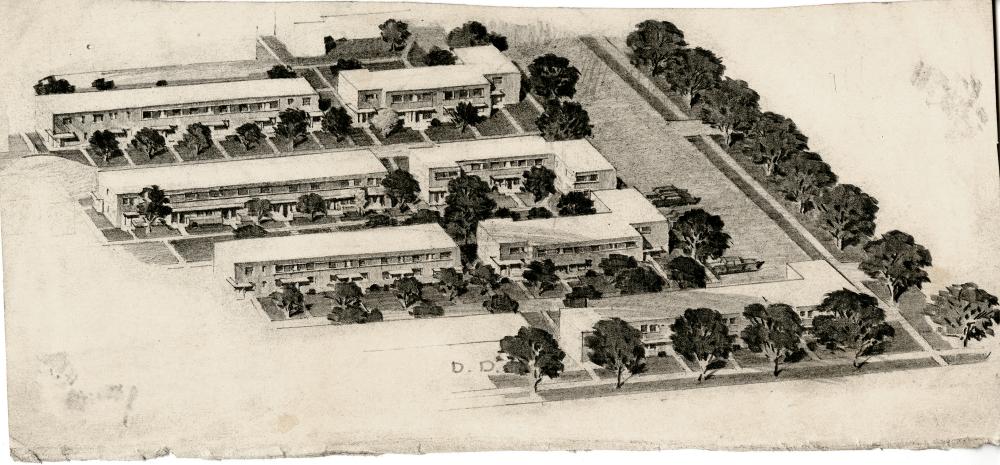

These external, sweeping lines are most evident when viewed from a distance. They are likewise manifest in the few perspective drawings that remain of the project. One image shows the ways that Kamrath fully developed the spatial and form-based properties of San Felipe Courts (Figure 4). In contrast to the project’s brown, red, and cream coloration, this image depicts the superblock structures in monochromatic white. It is unclear if at this moment Kamrath toyed with another type of material. As represented in the drawing, however, San Felipe Courts strongly resembles the white box modernism of the International Style. For pedestrians, however, San Felipe Courts communicates less about movement and more about enclosure and stasis. This is felt most acutely in the interpenetrating courtyard spaces that Kamrath threads throughout the superblocks. These courtyards, which now feature monumental oak trees, have the intimacy and scale of an outdoor room.

The superblocks consist of a string of long, shallow block units, aligned in a series of parallel rows around Valentine Street. The communal spaces—an interwoven network of pedestrianized green cul-de-sacs—and their purposeful separation from the vehicular traffic suggest a new vision for the urban neighborhood (Figure 5). The superblocks are arranged so that the parallel buildings’ longer sides face north and south. This orientation was intended to allow for maximum ventilation and access to light, a “climate responsive” design strategy that was often deployed throughout earlier European social housing experiments. [15]

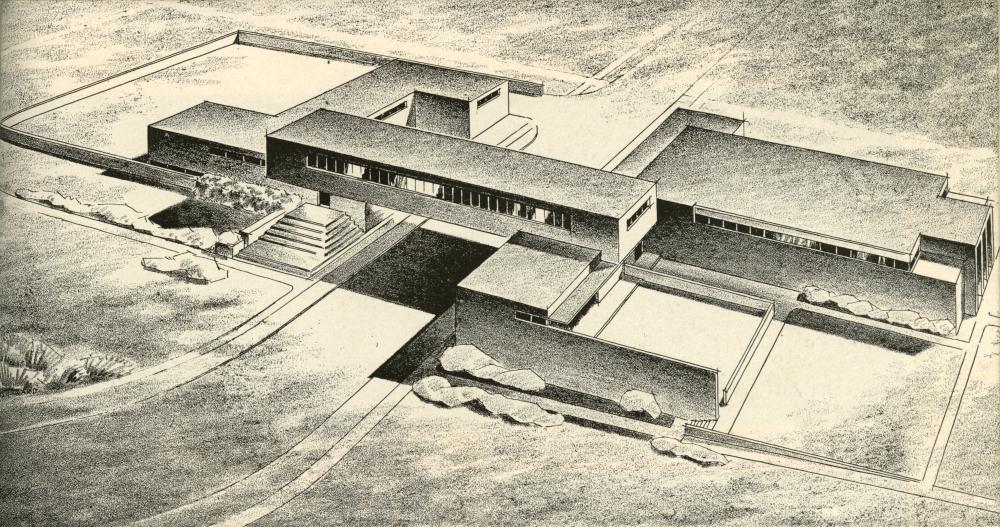

Another significant aspect of Kamrath’s design was the proposed community and administrative facility (Figure 6). Unfortunately this project center, which the Architectural Record described as “remarkable,” was never fully achieved since construction was “suspended in order to conserve essential materials” in light of wartime shortages. [16] The multipurpose building, a series of interlocking rectangular spaces, would have bridged Valentine Street, acting as a gateway into San Felipe Courts from the Buffalo Drive greenbelt (Figure 1). In his survey of Texas architecture, architectural historian Jay C. Henry observed that the “dynamic asymmetry of the plan and massing” would have made the project center “one of the most advanced modern buildings in Texas.” [17]

Although some of the communal buildings were ultimately created, the connector structure was eliminated from the final design. In addition to office and administrative space for the Houston Housing Authority, the center was to feature a communal facility equipped with a clinic, preschool, library, auditorium, and shop space. This facility suggests a democratic and communitarian vision for the urban neighborhood: a self-contained unit that synthesized innovative design strategy with access to green space and collective resources.

In designing San Felipe Courts, Kamrath mined a rich history of modernist community planning, including European social housing prototypes and earlier public housing developments in the United States. Its pedestrianized superblock buildings—interlaced with semi-enclosed “outdoor rooms”—is resonant of earlier Garden City models. Exemplars such as Sunnyside Gardens (Queens, New York, 1924–1929) and Radburn (Bergen County, New Jersey, 1929) emphasized decentralized green urban spaces. Similarly, homes were oriented away from the road and onto contiguous park space, thus limiting traffic flow and in turn emphasizing “community equipment” such as gardens, neighborhood centers, and recreational space in an attempt to promote communal living. [18]

The architectural merits of San Felipe Courts have been lionized since its inception. In his introductory remarks at a 1993 field hearing before the subcommittee on Housing and Community Development, chairman Henry B. Gonzalez stated that the project, which had been later renamed Allen Parkway Village, was “probably the best designed, fundamentally, and from an aesthetic as well as functional standpoint, public housing project in the country. It won an award in 1943 when it was built. We think it is indispensable.” [19] It is for this reason that San Felipe Courts was the first public housing complex in Texas to be listed on the National Register. As architectural historian Stephen Fox has argued, San Felipe Courts warrants such a designation because its design and planning exemplify the distinct—albeit short-lived—New Deal effort to provide quality housing for low-income families. [20] At an architectural scale, it is this lineage that San Felipe Courts draws on; the project’s aesthetics alone communicate a compelling statement about what Houston owed its poor in the form of shelter. Yet in creating an isolated “total” environment, how did a project like San Felipe Courts impact those beyond its boundaries? From the local perspective, San Felipe had a very different narrative.

Mapping Houston’s Fourth Ward

Though many Black residents would eventually relocate to the Third and Fifth Wards, the Fourth Ward—or Freedmen’s Town (as it was known eponymously)—retains, even to this day, historical memories of a flourishing African American community of the early twentieth century. A confluence of Black-owned businesses, eateries, churches, and music halls were concentrated within the neighborhood, generating Houston’s own “Harlem-like environment.” Development initiatives during the 1920s, however, changed the neighborhood irrevocably and altered its presence as a center of Black life. This process began with the Jefferson Davis Hospital complex, built in 1937, and was followed swiftly thereafter by San Felipe Courts, which required the demolition of thirty-seven acres of existing housing stock. [21]

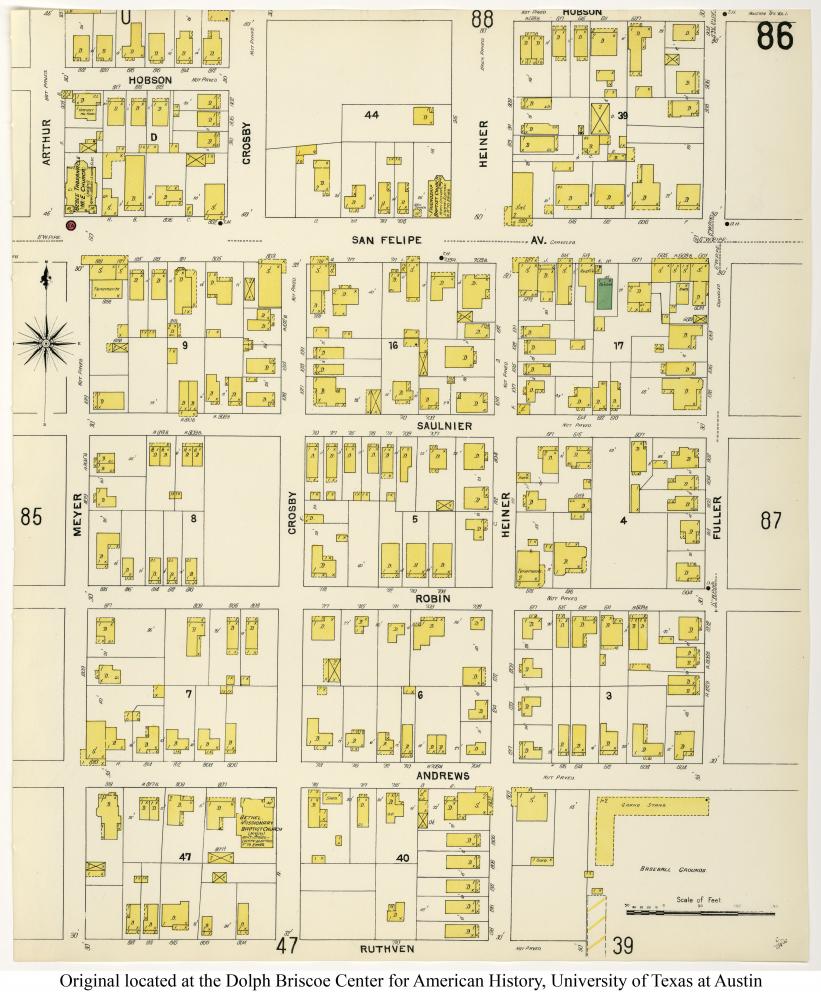

Maps of the neighborhood provide some idea of the larger Fourth Ward’s built landscape before it was redeveloped. Although Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for the city of Houston are incomplete, the 1907 survey illuminates the neighborhood’s spatial, domestic, and institutional environment. In 1907, the community is comprised almost exclusively of timber frame, detached houses located on tightly-spaced lots (Figure 7). The rectangular, repetitious footprints of the dwellings suggest that these structures were simple shotgun cottages. Interspersed in the sprawling area were African American churches. On the corner of San Felipe Avenue and Heiner Street was the Friendship Baptist Church; at the corner of Arthur Street and San Felipe Avenue was the Bebee Tabernacle Church; and several blocks south, at the corner of Andrews and Crosby Streets, was the Bethel Missionary Baptist Church. All of the main streets circulating throughout this small snapshot of the Fourth Ward are marked as either “graveled” or “not paved.”

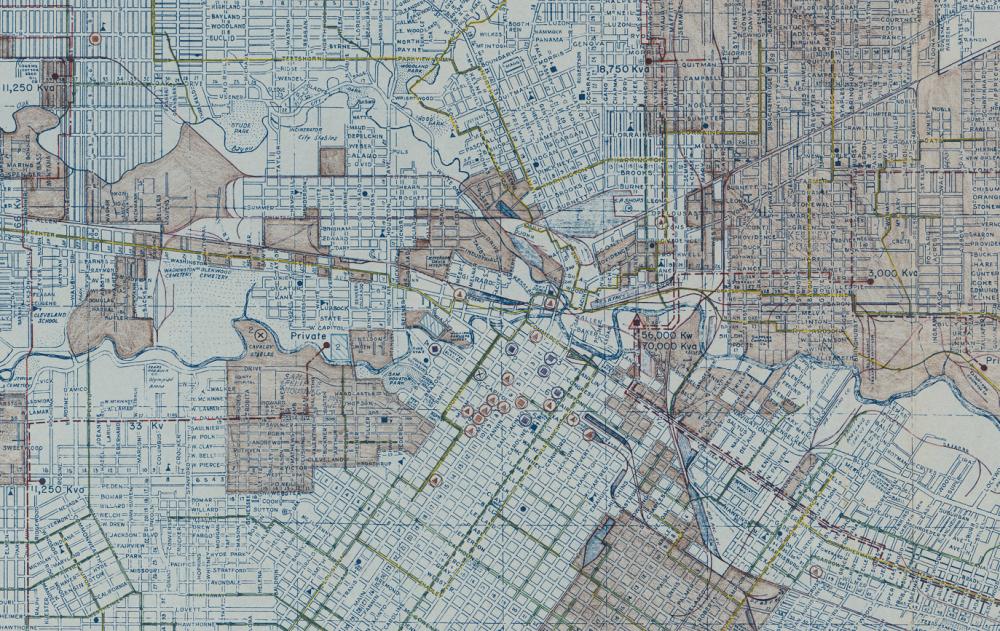

A 1937 Wellborn Map of Houston, labeled “Town Plan with Superimposed Information,” presents a more generalized view of street layouts immediately before the construction of San Felipe Courts (Figure 8). Several sections of the city—including the entirety of Freedmen’s Town—are labeled in red. This color blocking suggests racial redlining, or at least an attempt to identify the less desirable land tracts within the neighborhood. This is further affirmed by the fact that the Third and Fifth Wards, also home to large Black communities, are labeled in red while the white enclaves, such as the River Oaks suburb, are not.

GrangerFIG8_Preferred CROP.jpg

Prior to the construction of San Felipe Courts, the neighborhood consisted predominantly of modest shotgun cottages. The shotgun, a prevalent housing type throughout cities of the American South, is a simple, timber frame structure. Rectangular in form, the house type appears in linear rows along the streetscape. In spite of their simple form, shotguns often presented notable moments of architectural embellishment, including pedimented rooflines with decorative gable tracery. [22] John Michael Vlach has traced the origin of the shotgun cottage to free Black communities in New Orleans and within the larger Gulf region. [23] As Fox notes, the shotgun house was equally pervasive in Houston, and served as a prevailing housing type in African American working class communities. [24] This fact is corroborated by a 1937 aerial photograph of the Fourth Ward that depicts the recently constructed Jefferson Davis Hospital complex, surrounded by the rhythmic, linear layout of simple shotgun homes (Figure 9). In many ways, the shotgun house became a racially- and economically-coded form. “From a white perspective,” writes Fox, “the shotgun cottage was socially constructed as ‘Negro’; from a white and Black middle-class perspective, it was socially constructed as ‘working class.’” [25]

Kamrath’s modernistic brick design for San Felipe Courts was a reactionary response to the built environment of the Fourth Ward. It challenged the pervasive urbanism that, through the example of the shotgun cottage, was “deeply enmeshed in larger cultural debates on race and authority in the city.” [26] The gradual collapse of the Fourth Ward exemplifies the potentially violent nature of architecture, by which city leaders and developers activated the built environment as a tool to uproot the Black community.

San Felipe Courts—and other contemporaneous, if more modest, housing developments throughout the city—were the products of the converging forces of slum redevelopment and city modernization. In 1939 the Houston Chronicle described the city’s population boom of the previous decade, and the subsequent lag in the building industry to keep up with housing demand. Between 1931 and 1936, new home building only accounted for 88 percent of the city’s population gain. [27] Population growth coincided with slum clearance initiatives enacted at both the local and the national scale. Newspaper reporting from the 1930s gives us a sense of how Houstonians perceived slum spaces within their city. One article from 1937 describes, “40 and 50 dilapidated frame ‘shotgun’ shacks crowded together on one block,” “jammed” side by side and littered with “narrow alleys.” [28] Here the shotgun model is literally equated with slum living. E. M. Biggers, the chairman of the newly created Houston Housing Authority, described slum housing as a personal threat to his own health:

I would not want the servant who comes to my house to care for my children or cook my meals to live in such a place. I would not want an employee of a laundry who lives in one of those disease breeding slums to handle the clothing that I will wear. It is for the good of our health and welfare that these areas be cleaned up and the entire housing authority committee is determined to do this. [29]

With the help of federal funding, the HHA dispatched fifty surveyors in 1939 to assess homes for slum clearance. Several articles written at this time outline the procedure of how enumerators approached the dwellings, the kinds of questions they were to ask, and how the HHA defined a “substandard dwelling.” Though there was “no specific definition,” candidates included properties without running water, modern plumbing, electricity, or gas, and with overcrowded units. [30] From the findings of this citywide slum assessment, the federal government issued $11,118,000 to the local housing authority to erect low-income units. The first of these was the Cuney Homes, built for African American residents in the Dowling section of the city. [31] By late 1939 and into early 1940, San Felipe Courts and at least five other projects were either in early conception or construction phases. A Houston Post article from January 3, 1941, mentions the approval of a bid for $2,517,353 in construction costs for San Felipe Courts, a project consisting of eighty buildings to house one thousand white families. [32]

As soon as the project hit the news, it was greeted with protests from Black residents. On March 30, 1940, the Informer, a prominent African American newspaper, ran the headline “Home Owners Protest Small Value Placed on Property by Government in Fourth Ward.” [33] By the next month local residents had hired lawyers from Washington D.C. to protest the decision to buy land with, according to another headline, a “Fear [that] Ouster Would Be Prelude to Exodus of 4th Ward Negroes.” [34] Another article from that same month entitled “Lawyer Takes Slum Clearance Fight to Capital” outlines the conflict. Frank Spata, an attorney representing neighborhood residents, argued that “the property owners do not protest a housing project, nor do they disapprove of a slum clearance project, but feel that the Houston Housing Authority has made an unwise choice of locations.” He noted that the community’s main objection was “that Negroes have occupied the section for about 50 years and the project would be given over to white families.” L. S. White, a local Black minister and community leader, asked the pointed question, “Why not clean it up and let Negro people live there since the area is already 95 per cent Negroes?” [35] The actual protest petition created and signed by 1,000 residents from the neighborhood offered insight into community opposition. It stated that residents had “endured the inconveniences and offensive odors from the dump, garbage, rubbish, creeks and mud-ponds until made habitable.” The Fourth Ward was, moreover, “in walking distance of the down-town bargain counters which the janitors, maids, butlers and cooks must seek in order to make their meager weekly wages run until the next pay-day,” while the neighborhood was situated near the “charitable hospital where Negroes must go for treatment because low wages will not permit them to enter other hospitals.” Incoming white residents to San Felipe Courts lacked “white churches, schools, nor social centers in this area.” The petition concluded that “we do not protest slum-clearance projects, they may be fine things, but we do think it unfair to set a white project in the center of a Negro occupied or Negro owned section.” [36] Throughout the spring of 1940 Fourth Ward residents returned weekly to testify publicly. The Informer’s headlines are revelatory: “Homeowners Mass To Fight Property Sale,” “Citizens To Fight Ejection From Homes To Finish,” “Colored And White Citizens Join In Fight To Retain Property.” [37] On April 27, the newspaper printed an editorial entitled “The Housing Authority Threatens,” which argued that “stripped of technicalities and fine dressing, the attempt to put white projects in the Fourth Ward is nothing but a deliberate grab of the land.” It referred to contemporary events to equate the actions of the local housing authority to those of Adolf Hitler:

When Germany wants to grab off another country, she manufactures a case of aggression by the country, goes in grabbing and threatening, and comes out with another hunk of land dripping with the blood, the sweat and the tears of a ravished people. The local Housing Authority is trying to prove that Hitler does not have any monopoly on the technique. [38]

Living under the reality of a segregated Houston, Fourth Ward African Americans derived communal support, resources, jobs, and a shared identity from their extant neighborhood and fought hard to prevent the imposition of a white residential community in their midst by city leaders who had launched a strategic move to push Black enclaves outside the center of the city.

Preserving San Felipe Courts: Renegotiating Identity

The more recent history of Houston’s Fourth Ward and San Felipe Courts shows how the project’s enduring spatial and architectural legacy has been renegotiated by community members. Since the project’s desegregation in the 1960s and subsequent life as public housing, San Felipe Courts has, to a great degree, been reclaimed by the Fourth Ward community. As Curtis Lang explored in this very publication, the project’s afterlife throughout the 1980s and 90s echoes its early narrative of spatial disenfranchisement at the hands of city officials and the ambitions of urban real estate. For in order to maintain the land parcel as public housing for the Fourth Ward, despite its purposeful neglect and mismanagement, African American residents and neighbors allied themselves with preservationists in a decades-long battle against the local Housing Authority’s efforts to demolish and sell San Felipe Courts in search of cash. [39] In testimony before a 1993 hearing regarding the potential demolition of the development, Lenwood E. Johnson, President of the Resident Council at Allen Parkway Village, stated: “Choice, like I have said, is a basic democratic principle. People should have the right to choose where they want to live. And this neighborhood, Allen Parkway Village, including Freedmen’s Town, has said again and again that they like their neighborhood.” Attesting to the resilience of Kamrath’s design, Johnson concluded simply that, “The apartments are pretty, they are beautiful apartments.” [40] In her testimony, Gladys M. House, president of the Freedmen’s Town Association, equated the demolition of Allen Parkway Village with yet another attack on Black Houstonians. “This neighborhood,” to quote House, “was founded by freed slaves, some of my relatives, of course. And the original Freedmen’s Town was based right here on Allen Parkway Village.” [41] Architectural historian Stephen Fox followed this testimony by stating, “It is recognition of the fundamental worth of Allen Parkway Village as an exemplary planned residential community that has encouraged residents to advocate its preservation and rehabilitation.” [42] Despite such public outcries, many of the original Kamrath buildings were demolished, replaced by an outer ring of townhouse units that are still in use by the Houston Housing Authority (Figure 10). Though the property was never sold to a private developer, the rest of the Fourth Ward—ideally situated adjacent to the downtown—has not fared as well against the forces of gentrification, where new, market-rate multi-family units for young professionals now sit alongside the historic shotgun cottages. [43]

When contextualized within the larger body of writing about public housing in the United States, the history of San Felipe Courts parallels other projects throughout the country, but it likewise demonstrates how design politics became localized in distinct and at times unjust ways. The 1937 Housing Act, unlike its Public Works Administration predecessor, granted municipal housing authorities a great degree of freedom in both constructing and managing subsidized housing developments. This reality intersected with the valences of urban life in Houston: the machinations of Southern progressivism; the vernacular of Gulf Coast shotgun housing; and the struggle of Freedmen’s Town to retain social, material, and economic autonomy in light of a city that increasingly envisioned itself as a wholesale landscape open for “development.” It likewise explains the tension between the “progressive” formal narrative of San Felipe Courts—one of egalitarianism—and the curated spatialization of the project—one of selectivity. Much research has yet to be done in exploring further how public housing policy filtered down into various locales throughout the United States. As this case study in Houston demonstrates, the design politics at the core of San Felipe Courts—which were immediately perceptible to Fourth Ward residents—radiated out from the building at multiple levels, manifesting not simply in built form but also in the manner in which the development transformed its surrounding neighborhood and the larger cityscape, launching a legacy that still reverberates today.

Willa Granger is a doctoral candidate in Architectural History at the University of Texas at Austin. With a methodological interest in cultural landscape and vernacular fieldwork, her research works to situate people, buildings, and place under the critical imperatives of spatial justice and social history. She is currently completing her dissertation, an architectural and cultural history of the American "home for the aged."

An extended version of this essay, which was awarded the Southeastern Society of Architectural Historians’ 2020 publication award for Best Journal Article, was previously published in the Spring 2019 issue of Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum.

Notes

[1] Henry-Russell Hitchcock, “Introduction,” in Ten Years of Houston Architecture (Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum, 1959), 11.

[2] Architectural Record dedicated several pages in its April and May 1942 volumes to documenting San Felipe Courts, a “low-rent housing project [that] merits special study.” See “War Needs—Housing,” Architectural Record 91 (April 1942): 47–50; “War Needs—Community Facilities: Project Center Building,” Architectural Record 91 (May 1942): 52–53.

[3] The Zeilenbau typology was popularized throughout Germany and other European countries during the 1920s and 1930s by practitioners of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). It typically featured a series of parallel building slabs several stories high, arranged in rows and often oriented to capture sunlight and cross-ventilation. See, for example, Mart Stam’s 1930 design for the Hellerhof-Siedlung, part of the larger Das Neue Frankfurt development.

[4] Stephen Fox, “San Felipe Courts Historic District,” Houston AIA Newsletter 6 (June 1988): 2.

[5] George Lipsitz, “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape,” Landscape Journal 26, no. 1 (January 2007): 10–23; Lawrence Vale, Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

[6] The work of architectural historian Stephen Fox and historian Robert B. Fairbanks, respectively, is foundational for this study of San Felipe Courts. Fox has played a crucial role not only in documenting the project but also in advocating for its preservation during the 1980s and 1990s; this includes his work as the project historian on the project’s National Register of Historic Places nomination form. Robert Fairbanks has written about the larger dynamics of the “War on Slums” in southwestern cities such as Houston. His research is useful in understanding the chronology of the Houston Housing Authority (HHA), including the organization’s early public housing initiatives. Though Fairbanks only dedicates a brief section to San Felipe Courts (and neglects an architectural analysis), his synopsis of the racial tensions that underlay the project is crucial to this research. See Robert Fairbanks, The War on Slums in the Southwest: Public Housing and Slum Clearance in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, 1935–1965 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014), and Stephen Fox, “Allen Parkway Village,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form, Texas Historical Commission, Austin, February 16, 1988.

[7] Lawrence Vale, From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000), 4–5.

[8] Both the HHA and the Boston Housing Authority selected slum redevelopment sites along a “protective edge”—i.e., a highway—as a mechanism to build monolithically and, in turn, erase the “economic liability” of preexisting slums. Vale, From the Puritans to the Projects, 191.

[9] Vale, Purging the Poorest, 31–32.

[10] Jan Lin, “Ethnic Places, Postmodernism, and Urban Change in Houston,” Sociological Quarterly 36, no. 4 (Autumn 1995): 629–47.

[11] “War Needs—Housing,” 48.

[12] “War Needs—Housing,” 47.

[13] “War Needs—Housing,” 50.

[14] Stephen Fox, “Allen Parkway Village,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form, Texas Historical Commission, Austin, February 16, 1988, 1.

[15] See, for example, Das Neue Frankfurt (1925–1930), which was intended as a salubrious “remedy” to the ills of the city. Gabriella Gutierrez and Deborah Morris, “The Architect’s Role in Reshaping Public Housing Policy,” in Defining the Urban Condition: Accelerating Change in the Geography of Power (Lisbon: ACSA European Conference, 1995), 431.

[16] “War Needs—Community Facilities,” 52.

[17] Jay C. Henry, Architecture in Texas: 1895–1945 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993), 288.

[18] Kermit C. Parsons, “Clarence Stein’s Variations on the Garden City Theme by Ebenezer Howard,” Journal of the American Planning Association 64, no. 2 (1998): 130.

[19] United States Congress, House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, Subcommittee on Housing and Community Development, Rehabilitation of Allen Parkway Village, Houston, TX: Field Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Housing and Community Development of the Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, First Session, Houston, Texas, Tuesday, December 14, 1993 (Washington: USGPO, 1994), 2.

[20] United States Congress, Rehabilitation of Allen Parkway Village, 30.

[21] Steven R. Strom, Houston Lost and Unbuilt (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 18–19.

[22] Jay D. Edwards, “Shotgun: The Most Contested House in America,” Buildings & Landscapes 16, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 74.

[23] John Michael Vlach, “The Shotgun House: An African Architectural Legacy, Part I,” Pioneer America 8, no. 1 (January 1976): 49.

[24] Stephen Fox, “The Shotgun Cottage in Houston: A Brief Overview,” in Row: Trajectories Through the Shotgun House, ed. David Brown and William Williams (Houston: Rice University School of Architecture, 2004), 33.

[25] Fox, “The Shotgun Cottage in Houston,” 35.

[26] Edwards, “Shotgun: The Most Contested House in America,” 62.

[27] “Housing Officials and Newsmen Visit Shacks to Be Demolished Here,” Houston Chronicle, January 28, 1939, 7.

[28] Gordon Turrentine, “Houston’s Slum Clearance Plan: Federal Housing Program Making Rapid Progress,” Houston Press, February 1, 1939, 2.

[29] “Biggers Hits Slum Tenant Exploitation,” Houston Chronicle, February 16, 1940, 22.

[30] “Fifty U.S. Enumerators Start Ringing Door Bells, Asking Houstonians About Their Living Conditions,” Houston Chronicle, May 4, 1939, 1.

[31] Turrentine, “Houston’s Slum Clearance Plan,” 2.

[32] “Housing Project Bids Approved,” Houston Post, January 3, 1941, section 1, 9.

[33] “Home Owners Protest Small Value Placed on Property by Government in Fourth Ward,” Informer, March 30, 1940, 1.

[34] “Homeowners Mass to Fight Property Sale: Fear Ouster Would Be Prelude to Exodus of 4th Ward Negroes,” Informer, April 20, 1940, 1.

[35] “Lawyer Takes Slum Clearance Fight to Capital,” Houston Post, April 21, 1940, section 1, 11.

[36] “Protest Petition of Residents of Proposed Housing Project No. 5–4 Known as the San Felipe Area in Houston, Texas,” Law Offices of Gordon and Spata, Houston Metropolitan Research Center, MSS 210, Box 3, File 11, “4th Ward Re-Development Opposition, 1940 (Photographs and Documents).”

[37] “Homeowners Mass to Fight Property Sale: Fear Ouster Would Be Prelude to Exodus of 4th Ward Negroes,”; “Citizens To Fight Ejection From Homes To Finish,” Informer April 27, 1940, 1; “Colored And White Citizens Join In Fight To Retain Property,” Informer, May 4, 1940, 1.

[38] “The Housing Authority Threatens,” Informer, April 27, 1940, section 2, 2.

[39] Curtis Lang, “A Depleted Legacy: Public Housing in Houston,” in Cite 33 (1995): 10-15.

[40] United States House of Representatives, Rehabilitation of Allen Parkway Village, 20.

[41] United States House of Representatives, 22.

[42] United States House of Representatives, 30.

[43] The “ethnic place demolition” of Houston’s African American neighborhoods endures today, notably in the Third Ward, where a group of small grassroots organizations such as Project Row Homes work to protect the neighborhood against the encroachment of developers.