This article is the second of a two-part series by artist Carrie Schneider coinciding with the reopening of Emancipation Park. Click this link to read the first part: Emancipation Park Emancipatory Art: Flipping the Gentrification Playbook.

It’s Tuesday and you walk in the two story on Holman where Project Row Houses offices, or their boardroom on Elgin housed beneath the El Dorado Ballroom, or the SEARCH House of Tiny Treasures on Francis, or Houston Praise and Worship Center on Live Oak. Leaders from all of these entities and more have come together to make an anti-gentrification coalition called the Emancipation Economic Development Council (EEDC) that is redeveloping a historic African-American neighborhood without displacing the existing communities.

Assata Richards, director of Sankofa Research Institute, is speaking, or Ryan Dennis, the public art director of Project Row Houses, or Ola Tucker, resident organizer of an upcoming Mother’s Peace Walk. One of them is Eureka Gilkey, Project Row House’s Executive Director, who previously worked with President Obama from campaign to inauguration and as the White House Liason for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. And there are more. An urban planner and environmentalist. A retired minister. A Vice President of the University of Houston. A new charter school CEO. The principal of Blackshear Elementary.

You know who everyone there is because everyone there is asked to introduce themselves out loud and mark their presence beyond the sign-in sheet. Somehow it all fits even though the meetings end on time and there are lots of laugh breaks between items on the printed agenda. By the end, the official description of the EEDC — “a collaborative of organized, informed and engaged faith-based organizations, nonprofits, community development corporations, businesses, local government entities, and other stakeholders whose mission is to inspire hope and contribute to the revitalization and preservation of the Emancipation Park neighborhood of Third Ward and whose vision is a resilient, dynamic, and economically prosperous community where people live, work and thrive in a historically and culturally rich African-American neighborhood” — is not just an idea but a process that you are watching being set in motion that you have become part of.

Horizontal Structure

The start of the EEDC can be traced back to a course that Rick Lowe led at MIT in which he brought students to the Third Ward to engage residents and institutions in a discussion of planning. After the conclusion of the course, the discussion continued. In addition, both the Kinder Foundation and Houston Endowment had committed funds to the remaking of Emancipation Park. Project Row Houses became the fiscal sponsor for the $460,000 grant from the Kinder Foundation for the activities of the EEDC. The Houston Endowment has funded a feasibility study for a Financial Opportunity Center and a civic art plan. In addition, a coalition of nonprofits that includes Project Row Houses, the Northern Third Ward Consortium, has received a $100,000 planning grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation to develop a comprehensive, resident-driven revitalization plan for the Northern Third Ward. The Houston Southeast management district is also updating its master plan. In other words, there is an unprecedented, structured collaboration, instigated in large part by an arts organization, focused on public policy, investment strategies, community-based organizational work, and improved models for public service.

The EEDC has a horizontal structure with one community coordinator, Bianca Mahmood, and about six working groups. For example, the "Community Land Trust & Housing Choice" working group has several initiatives including a micro-housing feasibility study and an awareness program on community land trusts and housing rights. The "Community Wealth Building and Resident Engagement" working group is organizing employment placement for young mothers and a neighborhood cleanup program.

On this Tuesday, September 13, 2016, a working group called "Ujima Third Ward Resident Engagement", is talking about simultaneously improving and telling an improved story about “The State of Education in the Third Ward.”

A teacher at Baylor College of Medicine Academy at Ryan Middle School describes the difficulty of “recruiting” kids from the neighborhood back to “Ryan.” Some in the room hear this while registering that the school being discussed opened first as Yates High School for African-Americans, was later made into Ryan Middle School, desegregated in 1970, and declined through decades of disinvestment. Some in the room fought its closure in 2013 when it served 85 percent African American students. Now only 2 percent of the students at Baylor College of Medicine Academy at Ryan Middle School are from the neighborhood. Some in this room ask the same question about the Emancipation Park renovation as they do of the school overhaul: “Who is it for?”

Also at this meeting are parents of the new Baylor College of Medicine at Ryan Middle School students, perhaps who dropped them off at school and spotted the surroundings, thinking, “These houses are so cheap, and property values are going up, and so close to downtown, and so many artists, and you know the park,” because Emancipation Park just down Dowling Street has received a massive influx of investment, and that shining sign is a great assurance to investors.

Let’s pause that thread, and pivot to the power of such signals, because since that time, Dowling Street itself has been renamed.

Reclaim the Space / Rename the Street

At the EEDC meeting on September 27, 2016, Richards said, “We’re not just advocating something that supports us — but something that supports equity and access. Not just what we want, but what we want our city to be.” She was talking about the renaming of Dowling Street to Emancipation Avenue, which passed City Council on January 11, 2017. That it passed City Council is itself a remaking, because the EEDC not only participated in Garnett Coleman's fight to rename the street bordering Emancipation Park, but also fought for a new process of street renaming itself. The hope was that the city would adopt a new process of street renaming itself to include resident voices, not just property owner votes. Street renaming has required 75 percent support from owners along that street. With the naming of Emancipation Avenue, EEDC advocated for a new process by which the planning commission hears and City Council votes on street name changes informed by a majority of resident voices. So far, Mayor Turner has justified the name change on making the name of the street consistent with the name of the park but the EEDC sought not just to name this street, but for a new policy to shift how streets are renamed.

Remaking not just a made thing, but the process of making itself. For example, The Ujima House, named after the third principle of Kwanza, Collective Work and Responsibility, is a new community resource room at 2501 Holman. In answer to resident input about priorities that are relevant to them, it provides employment and housing resources. It is also meant as a meeting ground where grassroots community leadership might grow into the form of a resident-generated civic association. Simultaneously, the EEDC is not just attempting to add another Houston civic association, but to expand the possibility of who may comprise a Houston Civic Association to, again, include renters. With this expanded resident input, they have identified seven early impact projects piloted by the six different working groups that comprise the EEDC. The projects include the design charrette pictured here, a neighborhood cleanup, and a community land trust education campaign. They range from infrastructure, events, to art projects. They are intertwined, in proximity, and informed by each other.

Reframing Gentrification and the Role of Art

In fact, at this same EEDC meeting it is mentioned that a Third Ward Coloring Book is in the works by art collective Otabenga Jones & Associates. Then there is a request for artists to help decorate the Ujima House. Then resident Ola Tucker speaks. She speaks about her two sons, Demarcus and Daquarius, who were both killed by gun violence on the streets. The opportunities for young kids in this neighborhood. The economic impossibilities of trying to stay in this place. She talks about the lack of support for reentry after incarceration.

Ryan Dennis, Project Row House’s Public Art Director, chimes in about the People’s Paper Co-op from Round 44, whose art project is an act of erasure — getting people’s criminal records expunged.

Ola talks about how she is organizing a Mother’s Peace Walk because she doesn’t “want another mother — any individual — to feel alone.”

Ryan offers a description of how in 1999 a Colombian artist, Doris Salcedo, lined a two-mile walk in Bogota with red roses in a gesture of solidarity with those disappeared or silenced. She makes a point that art is not just decorating the Ujima house, “or art in huge things, but also … in small gestures of symbolic value that hold a level of beauty we don’t typically see.”

On November 19, 2016, the day of the Mother’s Peace Walk, they start from the space on the street where Damarcus’s life ended, people wore red and held balloons tied with loving messages to the lost, that they released into the air.

What role do these poetic ceremonies play in the EEDC’s claim, as Richards describes, that it is “not just trying to make suggestions regarding the gentrification set to overwhelm the Northern Third Ward, we are remaking the process of gentrification itself.”

Some argue that the term “gentrification” be reclaimed, that "gentrification" can mean economic opportunity for all, or even investment in a neighborhood without displacement. For most others, displacement of longstanding communities is exact what the word means. On Saturday, April 22, at a public panel on "Retelling the Taken for Granted: How to turn a story inside-out," Richards responded to such claims by citing the original coining of "gentrification" in 1964 by British sociologist by Ruth Glass: "One by one, many of the working class quarters have been invaded by the middle class --- upper and lower ... Once this process of 'gentrification' starts in a district it goes on rapidly until all or most of the working class occupiers are displaced and the whole social social character of the district is changed." The EEDC is unapologetic about its opposition to this meaning of the word and the manifold attempts to dress it up or let it masquerade as mutually beneficial. Richards, in calling out the origins of this word, dismissed such pretense and instead insisted on naming the EEDC's process on their own terms: community-driven redevelopment.

Which legacies get rebuilt, which words get recuperated, and which symbols get replaced have high stakes in this such work- its where public imagination intersects with public space, where the political and the poetic dovetail in this inquiry of remaking the world. Can the laying side by side of an old land use with a new possibility, a devastating loss with a gesture of hope, a block of disrepair into a row of rhythmically remade creative inhabitations, really outpace the logic of a market driven by profit to displace and replace communities of color with whiter, wealthier residents? As Audre Lorde says, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change … our personal visions help lay the groundwork for political action.” In the case of Project Row Houses, those who in our time are most sanctioned to have and express personal visions — artists — are supported to come up with new tools. In the case of Project Row Houses, those who imagine and image new possibles are invested in. In the case of Project Row Houses, those who in our time are most sanctioned to have and express personal visions — artists — are supported to come up with new tools, are believed in to imagine and image new possibilities.

Performing Another Possibility

Perhaps this is where the Project Row Houses aspect of the EEDC makes things unique, where the art angle and the community organizing are making an interesting intersection. Where transform really does mean changing shape, because while it takes actual political work to change the name and image of things, changing the name and image of things does actual political work. Consider the following moments of performance before city hall:

At the same meeting, Bianca Malmoud said, “We collected over 100 letters of support … I cannot underestimate the indignity of having a street named for a confederate hero running alongside Emancipation Park, and through the middle of one of Houston’s most culturally significant African American neighborhoods. The name of Dowling Street is an environmental microagression.”

It is obvious where the symbolic and political power overlapped in 1892, when the street along Emancipation Park --- the first public park in Houston purchased by the pooled money of community leaders who were formerly enslaved in order to have a place to celebrate Juneteenth --- was renamed from East Broadway Street for confederate General Dick Dowling. And how the name enforces which historical perspective on this space holds more authority in the imagination, and why what is held in the imagination impacts which bodies are welcome to use what space.

The name of one street occupies dozens of street signs, countless iterations of Google maps, numerous official documents, business correspondences, anchors endless community events held there — but larger still, the name holds space in each member of the public’s imagination, in the minds of each body constituting that public, of what has stood on that street and what the space stands for. In each of these iterations, the name of institutional racism and white supremacy has now been replaced with the name of the claim to the right to the city by all its inhabitants and the claim for complete emancipation and empowerment of black lives in American society.

But does renaming it Emancipation Avenue emancipate the avenue? The EEDC knows the answer is not all the way — that it still takes the ground work – but is also informed by a conviction that the only way to make a new world is to imagine it first.

One example occurred in 2003 when individuals at Project Row Houses initiated Row Houses Community Development Corporation “to develop housing for low-to-moderate income residents, public spaces, and facilities to preserve and protect the historic character of the Third Ward.” This initiative by a group of artists was subsequently criticized for providing 54 units within a massive deficit of some 500,000 units of affordable housing in Houston. It has also been defended for inserting this possibility into the public imagination in the first place, albeit on a symbolic level. Celebrated in its attention to the neighborhood's architecture, the dignity in its design and the care invested in its maintenance. For quality of home above quantity of emergency addressed. It may be a drop in the bucket, but the ripple effects can add up. In fact, another initiative of the EEDC's "Community Land Trust & Housing Choice" working group is to build the capacity of Third Ward community development corporations and non-profits. And as that capacity is built up, a faster pop-up effort took place: the Free Market Square events organized by the "Emancipation Corridor" and "Arts & Culture" working groups. Cedric Douglas, among other volunteers, helped facilitate a series of outdoor markets where local entrepreneurs sold their goods and services.

One of the most celebrated aspects about Project Row Houses among similar social practice offshoots (from the Project Row Houses-crediting Dorchester Projects in Chicago by Theastre Gates to the Creative Placemaking model that often funds artists to jumpstart economic potential of “underperforming” areas) is that behind, alongside, and hosted within this art space is the actual EEDC and its companion political projects.

These new efforts, along with the ongoing work of the Young Mothers Program and the Row House CDC, listed at https://projectrowhouses.org/social-safety-nets/ reflect and subvert a central challenge of social practice in our times — the neutering of art’s creative potential when artists are relegated to supplementing the services that the state no longer provides. Claire Bishop has pointed to this phenomenon since 2006 evidenced by the ameliorative role of artists in Thatcher’s UK. Since that time, this same criticism, in a context such as Texas in 2017, has been pressurized into a charge that artists, through socially engaged art, do find ourselves oddly rehearsed in social safety net repair at a time when it is desperately needed. We’ve trained up for this. But when called to task, will our art work? How can we take this up not as a mandate to merely mend rips in a withdrawing support structure, but to construct a new social fabric altogether?

Artists can never replace the massive amount of investment of all forms required for civilization. When we are substituted here it is to decorate its disappearance. As when arts nonprofits fill in the gaps of an education system in our city which allows property values to determine by default which schools get arts education, which kids living where are tested into labor and which are equipped to contribute to culture. The scale of our work is miniature, a scaled down model, in the face of the massive amount of work that is to be done.

But still I'm reminded of a talk that Ryan Dennis gave recently on the theme of social practice in the work of Paul Ramirez Jonas on the importance of the contracts that we make between ourselves. In a context where the commons has gated entry, the public is privatized, and larger social contracts between the state and the people ring hollow, the idea of social good disintegrates for individual ascension, our responsibility to "the unofficial oaths we take with people every day," is not just poetic but vital. A stitching of fiber to fiber, warp to weft on a lateral level. I'm reminded of Hannah Arendt's charge that making promises is how we make the future.

Never Done Before

The symbolic, political, and economic forces may well be lining up in the Greater Third Ward to do what has never been done in a historic African-American neighborhood in the U.S.: revitalize without displacing. As David Theis noted in his recent article for the Texas Observer, at the behest of State Representative Garnett Coleman, the Midtown Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ) has accumulated 4 million square feet of land (about 90 acres). In addition, churches and other institutions in the northern Third Ward own large portions of the land, often in the form of parking lots that are unused six days per week. How will all this land be used? For whom? If new housing is built, will it remain affordable over the long term? Will it foster an inclusive public realm? The role of artists in imagining a new future is potent here. In many ways they've imagined the future the EEDC is embodying now.

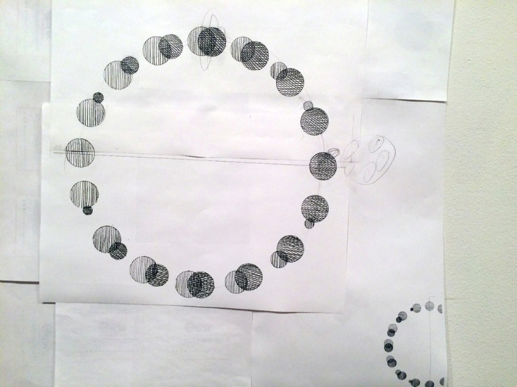

Recently Rick Lowe has been working on a drawing, a diagram of the poetic and political that reminds me of moon phases, in which the striped circles represent the utilitarian and the crosshatched ones the symbolic. I first saw it in a new class he teaches for the University of Houston on Socially Engaged Art where his students were plotting popular social practice projects according to both artistic merits and social accountability. Lowe said that the next draft will include a phase where the two intermingle, with no autonomous zone for either.

The EEDC’s approach seems to be to do both simultaneously. It will take time for the immediate gestures and the long term ripples to erode taken-for-granteds and build up new-possibles in the form of permanent change, but the waves are already in motion. And If you can’t wait for answers you can show up and join the room on a Tuesday, too.

Because as EEDC works to keep freedom in this space, not only for the passing through of bodies as shown in architectural renderings, but also for the actual movements of bodies that have claimed, reclaimed, and opened that space for all, what if meanwhile artists get uninterested in decorating or spiffing up real-estate space? What if we find it much more interesting to remake our cities on the terms of those it belongs to, remake it with those who make it with us? What if we aren’t here as the urgent, on-demand providers of life in corporatized and policed spaces? What if we want to move with the people who call our cities home? To echo Elaine Scarry in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, "Before there is making-real there is making-up."

Carrie Marie Schneider is an artist based in Houston. You can find her other contributions to Cite here. This article is the second of a two-part series, read part one here.

Further Reading

Hood, Walter and Carmen Taylor, "Musing the Third Ward at Project Row Houses: From Cultural Practice to Community Institution." Cite (96). Spring 2015.

Sperandio, Christopher. "Social Practice in the Time of Cholera: Can Mobility and Tiny Living Save an Art Form?" OffCite.org. April 2, 2015.

Binkovitz, Leah. "The Third Ward's fight to manage gentrification." Houston Chronicle. May 25, 2016.

O'Brien, Heather M., Christina Sanchez Juarez, and Betty Marin. "An Artists’ Guide to Not Being Complicit with Gentrification." Hyperallergic. June 18, 2017.

Theis, David. "Behind the New Look of Houston’s Oldest Park, a Complex Racial History." Texas Observer. June 19, 2017.