Friends of Polly Koch have organized a day of action Wednesday May 30, 2018, calling for safe streets for all. For more information visit safestreetshouston.org or the Facebook event page.

I have known Polly Koch for thirty years, starting in 1988 when I entered the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston just as she was on her way out and on the verge of finishing her first novel, published a few years later. I met her through Susan Jones, as new to Houston as I, and discovered in this lovely, reserved woman a mentor, a friend, an ally. A familiar. Our friendship grew, enough so that in 1992, born within ten days of each other, we celebrated our fortieth birthdays together, gathering our various friends for a bash in her small apartment on Bonnie Brae. She created the invitation, a line drawing of us chanting, fists raised, behind a banner that read: POLLY AND JANE BEGIN THEIR BEST DECADE YET — a promise grounded in the public/private turmoil of previous decades as feminists, anti-war activists, writers of and readers into our precarious times.

We had a great night, I think, but what I remember most is sitting on the couch in the half dark of the wee hours after everyone had left, her border collie Emma nestled on the rug at our feet. "I want," she said quietly, "to burn the whole world down." The line drifted into dim light, the edge of an epic sadness pulling against what had seemed just hours before a bet on the future. I looked at Emma. "But Polly," I said. "What about Emma? And what about the house I grew up in? Would that have to go too?" She laughed, a good Polly laugh. Emma lifted her head, and then laughter swallowed us both, full-throated, infectious, relieving.

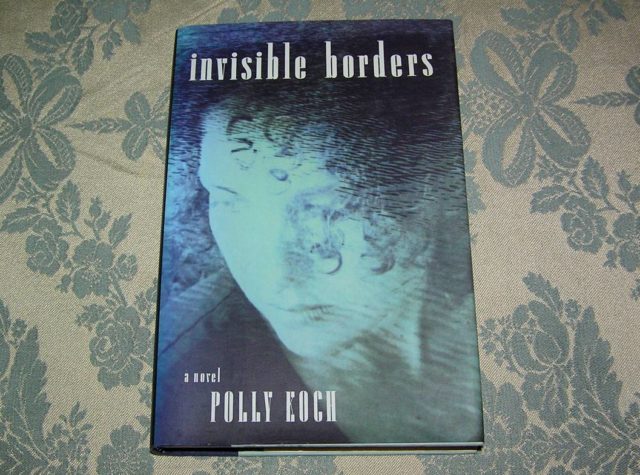

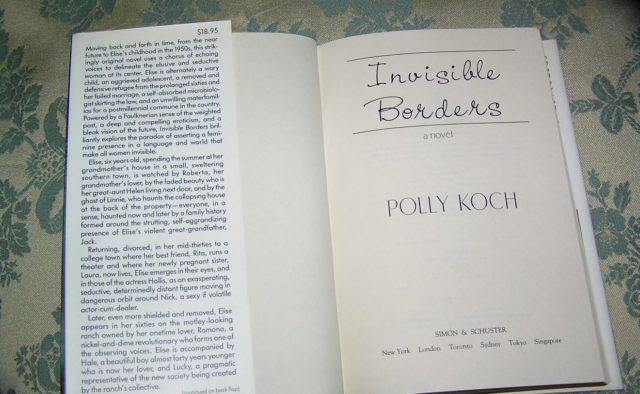

We lost Polly on November 28, 2017, at 8:30 in the morning, when she was struck and killed by a pickup truck while walking her two dachshunds in the pedestrian right-of-way on Richmond Avenue at Mandell. At the gathering to remember her held in January at Inprint, friends still reeling from the bewildering suddenness of her death spoke about that laughter and the pleasure they took in provoking it. Polly was 65 when she died, the same age as Elise, the protagonist of her novel, Invisible Borders, which looped through time frames ranging from 1954 to 2015. The book jacket properly evokes the novel's "Faulknerian sense of the weighted past;" yet that's the sort of evocation that can slot a novel into a category too difficult for many readers, as it seemed to for Simon & Schuster when the book suffered negligible promotion and was too quickly remaindered. Her friend Beth Alvarado was right when she wrote that Invisible Borders was "simply about 25 years ahead of its time."

Polly’s characters share an outpost commune in 2015, in a landscape blasted by errant ideologies and fundamentalisms, each of them surviving the way one might — pressed within and pushing against the invisible but deeply felt constraints of pasts that continuously permeate the present. The women central to the novel, each distinctly realized as sensually and intellectually complex, depart radically from any a priori notion of heterosexuality. They persist in a world marred by the legacy of violence — ecological, social, patriarchal. Elise's forebears are mid-century women haunted by a murderous, Snopes-like patriarch who reappears across time in surprising eruptions of both individual and collective consciousness. One could say that Invisible Borders picks up decades after Faulkner leaves off, but in ways completely original to this writer. She has wrought women poised at the edge of the 21st century, radically alive in their awareness of a bleak, beloved world. They are intimately imagined, their interior lives resistant to all orthodoxies of the feminine, their desires fully fleshed, erotic and complicated. The novel surprises at every level, from its stunning sentences through its fluid sequencing of time and character to its profound political vision of a dystopian world that is disconcertingly close, disconcertingly real. A novel of great currency, it is well worth reading in the present year.

Everybody seemed poised at the outer edge of a collapsed star, Elise amused by the conceit, smiling as she watched the distant farmhouse, the black canopy of trees, the star-washed sky. The dog whined and trotted into the dark. Anything pulled past the event horizon of a burnt-out star disappeared forever, squeezed out of existence at the singularity just beyond where laws of space-time broke down.

from "Prologue: 2015," Invisible Borders

Polly Koch

Its disappearance so soon after its publication is a fate shared by many first novels, a fact easy enough to repeat but wildly difficult to live. I remember a distinct moment sometime in the mid-nineties when Polly, in crisis, turned her back on literary fiction and rid herself of her formidable library all at once. I got the news in a phone call from her, and with it a whiff of her desperation, her end-of-the-road feeling, and more a sense now than clear memory that she was on the verge of destroying her manuscripts, present and past — what would be an incalculable loss of Polly's deepest explorations of this world. I mention this as a measure of what this writer went up against in dealing with depression and adversity, subjects she has been able to speak of and write about subsequently without fanfare, but with utmost clarity and empathy based in her own experience. She wouldn't see herself this way, but I think she was a woman of remarkable courage.

She showed that courage in her persistence, in her daily return to the things that mattered — family, dogs, friends, the power of language, the manuscripts of others, and always her own writing. Polly was reserved, choosing her time with people carefully and always returning to the apartment on Bonnie Brae to work, to write, to read. In all that time, for decades, she kept close track of her sisters, nieces, nephew, and grand-nephew. She took great care of her father through his late age and passing, and quietly told stories about him and them on our walks that were virtuoso performances of love, wit, and occasional exasperation. For the past two decades, she kept up in person with two close friends, visiting almost weekly with Elizabeth Gregory and her family, and walking almost weekly with me. We began around 2000 when I moved into my husband's house near Memorial Park. What I remember more as a rhythm of life than as a series of distinct episodes is our walking its three-mile loop once a week, according to an established pattern. She would show up at 7 a.m., push open the side door and walk through the kitchen straight into the sunroom where I'd just be lacing up my shoes while Jim sat reading and drinking coffee, happy in anticipation of a few minutes conversation with our wonderfully punctual friend. About a book he'd read that might interest her, about any penetrating mystery she might recommend to him, or about any entertaining wickedness they might observe in the latest episode of whatever they were both watching, e.g. Breaking Bad. Shoes laced, I'd stand, they'd wind it up, smiling and nodding, and off we'd go, a short drive to the loop, out of the car, check hat, sunglasses, keys, begin, she to my left, I to her right, clockwise, always the syntax of the walk in place.

I noticed this part of the syntax only after some time — how if I happened to start off on the wrong side, she would step around me to the left, or resist my suggestion that we try counter-clockwise, laughing about the need for order, a pittance of structure pitched against a world bound for chaos, and I'd be laughing too, because wherever we started out on the walk, sometimes either or both of us in some kind of flatness or distress, we would be lifted by the pace, the talk, the telling of dreams, the pleasurable complaining, the patience, the certainty of being heard. Over time I understood how much I depended on her walking just to the left of me, the ways she let me unawares set the pace according to whatever the condition of my aches or our moods, and matched me while we walked.

Polly made her living paying attention to pace, to sentences, to manuscripts, to the precision and accuracy of content. For a number of years she wrote astute mystery reviews for the Houston Chronicle. As a sought after editor and copy editor, she listened carefully to what her clients required and shepherded them with an occasionally acerbic but always compelling clarity, tending to the musculature of language and syntax in a wealth of contexts. She was by all accounts remarkable at it, widely regarded for her service to local, regional, and national arts organizations, including the Menil Collection, Fotofest, Blaffer Art Museum, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Rice Design Alliance. She worked intensively with a range of clients from corporations to individuals. Those who spoke at the memorial gathering spoke of how seldom they saw her but how intimately they experienced her edits and the accompanying commentary. Polly, they were clearly saying, was integral to the making of their work, integral to the way they thought about it, and fundamental to its prospects in the world.

She was always writing. Among the projects that will be discovered in her papers — drafts of what she called the mother book; a mystery novel; multiple manuscript versions of a major novel set in El Salvador that followed the publication of Invisible Borders, and which she was beginning to craft into a novella; her experiments in the essay that include a strikingly clear piece I recently read about the nature of suicide and what it means to resist it; extensive correspondence with writer friends and others across the country, a piece of which Susan Jones shared at the gathering. It's an email Polly wrote her when Susan couldn't see the point of writing anymore. I share a bit of it here:

"The reason for writing something," she said, "is not to send it out and get it published. Ahem, Emily Dickinson? . . . . the reason for writing a poem is to be writing a poem. It's to be in that state of creativity. It's to be observing in that kind of way. It is to satisfy an itch. It is to pass the time. There are a LOT of reasons to write a poem. It is to save your life. It is to leave a mark. It is to play. . . . . Susan, start writing again! It's what we do. It's what we have. Get out of your awful shutdown place." (July 13, 2017)

She believed in this, the lived nature of writing as a thing apart from its publication, saying to Susan in the same email, "I loathed the physical object that the Elise novel became . . . . It was too solid and done and alien." Writing as consciousness. It's what she did, our brilliant friend, so generous and so beloved.