After Harvey, Houston’s sprawling developments have been blamed for contributing to flooding of those downstream by paving over the prairies and ecosystems that once stored and drained water. The outer-ring suburbs of the Houston region, it turns out, are more complicated than that and, in some cases, have been places of design innovation that could teach the rest of Houston some lessons about living in floodplains.

The story of our flooding problem, like most environmental hazards, starts with natural resources sold as commodities. From about the 1830s to 1870s, “earlier settlers made a ton of money off plantations because [the land along Houston’s bayous] was so fertile,” says Keiji Asakura, Principal Designer at Asakura Robinson, a planning, urban design, and landscape architecture firm. Well before urbanization, farmers raising cattle and growing crops like cotton and rice fundamentally changed the soil. In addition, farm-to-market roads and railroads displaced organic drainage patterns. Coastal prairie that took root in Houston for thousands of years was decimated in a few decades.

Urbanization further altered soils and drainage. Bayous were dug up then paved over. More and more highways, more and more parking lots. And as the Houston Chronicle reported, the detention of water in new developments was not mandated until 1984 and is not enforced well over time.

In this past half-century, a different story has unfolded in some master planned communities along Houston’s periphery where designers and developers have tested bold ideas.

Design with Nature: The Woodlands

“Let us abandon self-mutilation which has been our way and give expression to the potential harmony that is man-nature…. To do this he must design with nature,” the chief landscape designer for The Woodlands, Ian McHarg implores in his book Design with Nature.

This principle — work with, not against, a site’s natural condition — was first promulgated in The Woodlands in the 1970s and continues to hold sway in developments surrounding Houston. Two of the most notable master planned communities currently under construction are Springwoods Village — just south of The Woodlands — and Cross Creek Ranch out in Fulshear. You wouldn’t guess it from the repetitious McMansions, but these three developments are unique — indeed, radical for their time — with their respect to the piney woods and coastal prairies they replaced.

The Woodlands was conceived from the most unlikely of sources: George Mitchell, an oil tycoon hoping to develop a piece of land thirty miles north of Downtown Houston along I-45. His conversion was recently written about in the Houston Chronicle by Loren Steffy and unfolds in greater detail in Ann Forsyth’s book Reforming Suburbia:

“McHarg suggested using the natural drainage system of the Woodlands site to structure development. This would, he noted, help reduce the prospects for flood damage. Ever the geologist, Mitchell asked. ‘All right, natural drainage works, but what does it mean to me?’ ‘First, George, it means you’ll get $50 million from HUD and, second, it will save you even more money,’ McHarg responded. ‘For instance, you won’t have to build a storm drainage system. This will save you $14 million for the first phase alone.’ And so McHarg converted the oilman into an ecologist.”

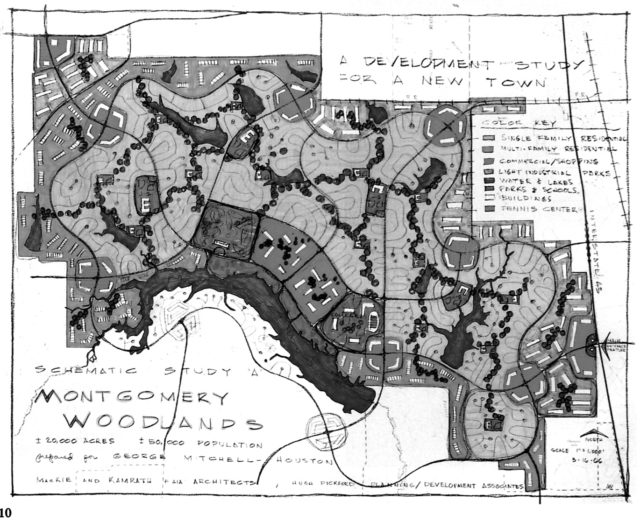

George Mitchell gathered the country's and state's best planners, including Ian McHarg of Philadelphia and Mackie and Kamrath of Houston to map out a concept for The Woodlands.

George Mitchell gathered the country's and state's best planners, including Ian McHarg of Philadelphia and Mackie and Kamrath of Houston to map out a concept for The Woodlands.

This conversation vastly underplays the technology needed to employ natural drainage systems. Dr. Phil Bedient, now a professor in Rice University’s Civil Engineering Department, reminisced about being a hydro-engineer on the project some four decades ago. A preliminary survey of the site showed Dr. Bedient and his team that one-third of the property was on the one-hundred year floodplain, with flat land and thick woods promising stagnant rainwater throughout. Undeterred, Mitchell and McHarg planned for retention ponds, golf courses, and forest preserves to be in the most flood-prone areas. This accomplished two goals: it kept personal property away from low elevation sites and instead programmed a dual purpose for recreation on otherwise clement days.

The early stages of planning had very little to do with return on investment for number of buildings on the land, rather “landscape [was] used very consistently as a basic framework underlying the urban design of The Woodlands, with villages, transportation corridors, and commercial centers having secondary importance” (Forsyth 175).

It was a special set of circumstances that made The Woodlands possible: I-45 had just been completed; the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department (HUD) had a well endowed yet unaccomplished new program, Title VII, for the country’s first round of master planned communities; and the Mitchell family could bankroll an entire city’s worth of development during the first few decades of growth. The Woodland’s greatest advantage, though, was having Ian McHarg as the lead landscaper. It was this canvas, in all its flood-prone glory, where he first applied this revolutionary theory of landscape.

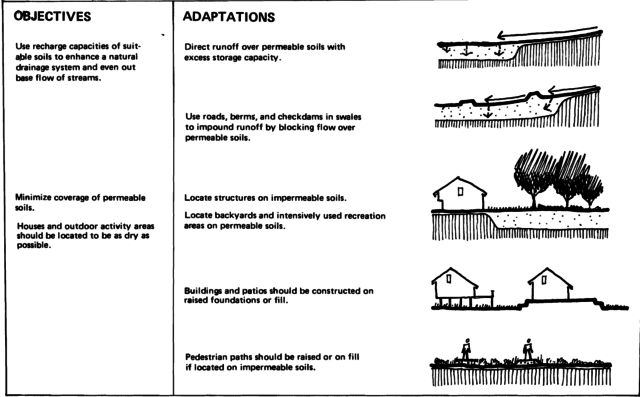

From Woodlands New Community, Guidelines for Site Planning, prepared by Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd, 1973.

From Woodlands New Community, Guidelines for Site Planning, prepared by Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd, 1973.

The Woodlands was indeed an anomaly for its time. Recent reincarnations copy the natural aesthetic of The Woodlands — its most lucrative attraction — and paste it onto landscapes without thinking through the differences in context. A retention pond with a fountain does not a Woodlands make. Most of the six-million-plus people in Houston’s metropolitan area live in these more mundane suburbs. I grew up in one myself. But the Greater Houston area has a handful of exceptional master planned communities improving upon The Woodlands legacy. I learned a bit about two of the most intentionally sustainable master planned communities currently being developed — Springwoods Village and Cross Creek Ranch — but the list could go on. Up in Cypress is Bridgelands, with landscape design by OJB which normalizes green roofs and rain gardens and in Fort Bend there is Harvest Green with landscape design by SWA. I will focus on just the two: Springwoods Village and Cross Creek Ranch.

Springwoods Village

Before writing this article, I knew that all the lakes in Texas were man-made and that all the “lakefront” properties of the suburbs were really retention-pond-front properties.

After interviewing Keiji Asakura about the planning of Springwoods Village, I came to realize these "fake" lakes represent a major shift. The goal of flood management infrastructure, especially after World War II, was to move large volumes of water away from development as fast as possible. This strategy didn’t work for a number of reasons, mostly because channel intersections became flooded bottlenecks. Not so nice to those downstream. (The master plan of Springwoods Village was a collaborative effort led by Design Workshop. Further development of the master plan and subsequent design/implementation has pursued as separate projects by Design Workshop, Clark Condon, and The Office of James Burnett. Asakura Robinson played a role in the development's alternative transportation planning.)

More recently, since the 1980s, the goal became “to first slow the water to lower the peak in any way we can,” says Asakura. The new question is how to create more time for rainwater thereby lowering peak volume? Rather than expunge rainwater as channels do immediately or detention ponds do eventually, retention ponds collect rainwater from the source and retain the water for slow evaporation into the atmosphere and percolation into the soil.

Retention ponds do one of two things that every landscape architect and environmental engineer seems to agree will mitigate Houston’s flooding: one is “holding water where it falls,” says Dr. Bedient and the other is “increase vegetation with good roots and open up that soil mass,” says Asakura.

This latter method, “good roots,” is the same one that I mentioned was destroyed by early settlement of the coastal prairie. The benefits of deep rooted, tall grass are numerous. Typical lawn grass sequesters approximately 100 pounds of carbon per acre. The grasses seeded in Springwoods Village and Cross Creek Ranch sequester 6,000 pounds of carbon per acre. They also are flexitarians, adept at absorbing large volumes of water or surviving without such luxuries.

You can very easily find both of these methods — the retention and the roots — in Springwoods Village. Off I-45 and Grand Parkway, you are immediately met with traffic medians lined with detention ditches for capturing water at the source. These medians, along with the lakes, parks, and all other opportunities for landscaping, were outfitted with tall grasses indigenous to the region. All of the utilities of a community have been bundled into its infrastructure, bringing together roads, pipes, drainage, and vegetation and freeing up the remaining space for parks, lakes, houses and, of course, ExxonMobil’s campus.

Indigenous wildflowers and grasses share the road with one of Springwoods Village’s many corporate campuses. Photo: Springwoods Village Facebook

Indigenous wildflowers and grasses share the road with one of Springwoods Village’s many corporate campuses. Photo: Springwoods Village Facebook

Cross Creek Ranch. Photo: Jonnu Singleton, courtesy of SWA Group.

Cross Creek Ranch. Photo: Jonnu Singleton, courtesy of SWA Group.

Cross Creek Ranch. Photo: Jonnu Singleton, courtesy of SWA Group.

Cross Creek Ranch. Photo: Jonnu Singleton, courtesy of SWA Group.

Cross Creek Ranch

Fifty miles west then south of Springwoods Village on Grand Parkway is Cross Creek Ranch. Houses there are suspiciously similar to those of Springwoods Village (and all their lakes similar to those of Minnesota), but the land upon which they stand are not. Despite driving past the same empty ranch and plantation land surrounding both developments, fifty miles of separation left room for the piney woods of The Woodlands to become the Katy Prairie of Cross Creek Ranch.

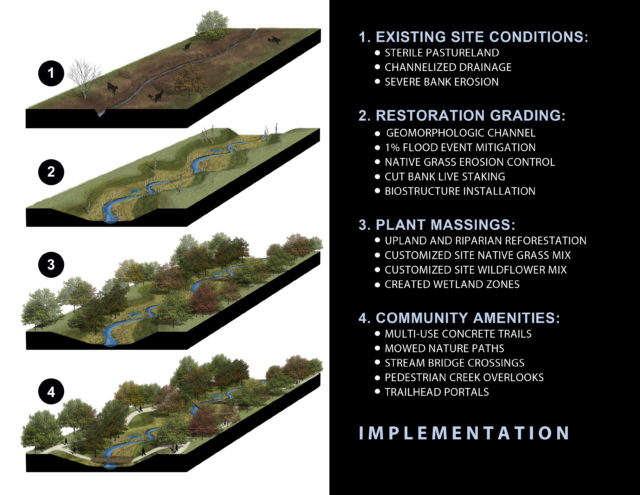

Johnson Development Corp. purchased the property as denuded pastures with the early intention of “doing something that was green and sustainable” says Matthew Baumgarten, SWA’s lead landscape architect on the project. They did so through a number of means, both familiar and novel. “Just like any other master planned community, there’s a very large basin that stores a one-hundred year event” but, on a normal day, it acts as a wetland park, says Baumgarten. There’s that dual purpose again. Like Springwoods Village, traffic medians at Cross Creek Ranch are lush with “Tall Grass Zones” and backyards are resplendent with lake views. There is also the development’s namesake, a three-mile long restored creek that used to be a watering hole for cattle.

Baumgarten planned for “all those things to look like landscape features” to the casual observer but subtly detain a “one-hundred year” flooding event. From my experience in Cross Creek Ranch, subtlety verged on invisibility. Finding the creek was surprisingly laborious: The band of bordering wetlands were maybe five to ten feet wide and recessed well below street-level. Once spotted, I arbitrarily parked and stepped into 110 percent humidity to walk through muddy, freshly mowed grass which gave way to unmowed, tall grasses and wildflowers recently soaked by rain the night prior.

At last, there was a narrow stream with a smattering of plant diversity modeled after the Katy Prairie. The creek resembles Buffalo Bayou Park, which is no coincidence. SWA’s success in creating a “synthetic nature” along the bayou caught Johnson Developers’ attention who requested a similar approach here. Unlike Buffalo Bayou Park, there weren’t paths or a recreational space to lure neighbors to the creek. This may explain why my guide, Christian, a five-year resident of Cross Creek Ranch, didn’t know there was an actual Cross Creek. His high school buddies and his little brother didn’t know they were participating in a natural restoration project either.

Reform

In the wake of Tropical Storm Harvey, flooding is understood as an existential threat to this region. As the Cite magazine editorial committee noted, “three major flooding events in little over two years time, the Memorial Day floods (2015), the Tax Day floods (2016), and now Harvey (2017)” that should only be happening once every century are symptoms of an ongoing crisis.

I began writing this article months before Harvey and the conclusion I had in the works is suddenly far more urgent. Though I have moved to Chicago, it is impossible for me to disconnect from the deluge of friends checking themselves in as safe, the articles proclaiming “catastrophe,” the texts and phone calls from friends and family promising me they are okay. The eyes of the world are on the place I will always consider home. And everyone has an opinion.

Journalists, experts, and politicians are keen to draw or deny a causal relationship between Houston’s lack of zoning and Harvey’s destruction. A voice that breaks through the discordant noise is Mayor Sylvester Turner’s who tweeted, “Zoning wouldn’t have changed anything. We would have been a city with zoning that flooded.” It’s tempting to overextend the importance of zoning, which is about separating different types of land uses (residential, commercial, industrial), and to equate the lack of zoning with Houston’s sprawl. What we lack in zoning inside Houston tends to be made up for with other types of development codes for everything from the number of parking spaces to elevation above the 100-year floodplain. Danny Samuels, Professor of the Practice at Rice Architecture, observes that “zoning made no difference” but newer houses up to stricter building code weathered the storm far better. In addition, Albert Pope, also at Rice Architecture, and many others have argued that we should not be building in the 100-year floodplain at all, and that vacating this space would open opportunities to organize dense developments around bigger green spaces. In other words, Houston would do well if it learned from and adapted lessons from its master planned fringes.

The Woodlands, Springwoods Village, and Cross Creek Ranch appear to be doing well, on the whole, considering the magnitude of the storm. The Woodlands had water on its streets during Harvey, and 220 people had to be rescued, or .2 percent of the total population, according to Steffy's report in the Chronicle, with "the hardest-hit areas bordered Spring Creek." Nearby, Springwoods Village volunteered themselves and their resources for afflicted Houstonians. About five houses flooded in the Audubon Grove section according to two sources. The Kinder Institute tool showing where buildings are expected to have flooded marks a few properties in that section of Springwoods Village along Spring Creek. I checked in with Christian about his family and neighbors in Cross Creek Ranch; he said they are “really lucky…no one got flooding in their house.” The systems the architects put in place appear to have performed the way they were designed to. They captured water and absorb it as quickly as possible.

While these master planned communities received Harvey well, they are not the solution to Houston’s flooding problem. Even if a single well-designed development manages to hold more flood water than before it was built, all the energy and infrastructure required to service it is not sustainable in terms of maintenance costs, carbon emissions, any other measures. Think of the billions spent on new and widened highways like the Grand Parkway. They are still suburbs and lack the diversity of uses, people, and building types that make cities thrive over time.

Neither the landscape architect, Asakura, nor the engineer, Dr. Bedient, expect Houston to be retrofitted along the lines of The Woodlands after decades of unconstrained development. But these case studies in sustainably designing Houston’s native ecosystems is evidence that the city can do better. That we don’t have to combat nature but can design with nature. That we must do better for more than just the folks who can afford a quarter-acre plot of land in a refurbished prairie or the 385-acre ExxonMobil campus in former greenfields. With the storm waters receded, it’s time for those who can plan for reconstruction to do so immediately.

My favorite issue of Cite magazine was published the Fall of 1997, when I was just two years old — Cite 39: Texas Places. The magazine opens with an interview of a personal hero of mine, Larry McMurtry, who is best known for his novel Lonesome Dove, which, for so long, I read as a tragic romantic comedy about Texas’ Wild West glory days. The interview reveals otherwise. McMurtry calls his work “a critique of…the myth of the cowboy” and expansion to the West “a failure because of the destruction of the environment, the landscape, and the indigenous population.” In the myth’s wake are ghost towns squelched of any optimism that settled the damned place.

It is unsurprising that McMurtry sets many of his novels and movies in Houston. Like the western plains of Texas, Houston “never really has been controlled…It’s always been fairly wide open, filled with graft and corruption.” Correlations between Houston’s unconstrained development and that of the Wild West have been made for as long as it’s been heralded America’s largest unzoned city. But this relationship is often used as justification for continued expansion. Our Manifest Destiny.

For so many years, development patterns in Houston have approached nature as an adversary, laying ever more concrete and exploiting its flat surface, ever chasing the bottom line. Perhaps Harvey has exacted extreme enough damage for us to take what has worked in a few parks and neighborhoods here and there, and scale up working with nature.

CORRECTION: In the print and digital versions of this article, the original text implied that the planning of Springwoods Village was carried out by Asakura Robinson. The master plan of Springwoods Village was a collaborative effort led by Design Workshop. Further development of the master plan and subsequent design/implementation has pursued as separate projects by Design Workshop, Clark Condon, and The Office of James Burnett. Asakura Robinson played a role in the development's alternative transportation planning. The text has been corrected.