When people apply through a government agency to receive services, they might wonder, “Why isn’t this an app? Doesn’t the government already have this information? Why am I filling this form out on paper?” The answer is often that government offices and nonprofit partners don’t have the internal capacity to manage large amounts of data or design public-facing portals. In cities, strong networks of data-sharing can allow governments and community organizations to build powerful interfaces that deliver services seamlessly and engage residents in the everyday business of governing.

Generally, local governments are sitting on mountains of data but struggle to use it. Most governments are in the early stages of internally using evidence to inform policy and operations. Many are in the first five years of programs that improve transparency and accountability through the publication of open data.

In Houston, data capacity in city government is multiple steps behind other cities like Chicago, Boston, New York, Los Angeles, or Seattle. One feature that sets these cities apart is that they have all had Chief Data Officers (CDOs) and robust data analytics teams since around 2014. Houston was among the first wave of cities to appoint a CDO, here called an Enterprise Data Officer, when the role was becoming popular around that time. Houston’s first CDO was Sindhu Menon, an IT executive who had formerly worked at the City of Dallas, but after Menon’s departure the job was vacant from 2018 until August 2021, when Raphael Louvrier, who previously worked as a data executive for an oil and gas company, was hired.

Having a CDO does not necessarily mean that City departments will automatically have better websites or stronger data offerings. But when CDOs are executives of their own data programs, they can inspire and convene data users from across social sectors like academia or community services to work together and improve the quality of public data. A strong CDO can deliver on promises to make cities more data-driven overall; this leadership can shift culture toward transparency, accountability, and collaborative data use in cooperation with planners, researchers, activists, neighborhoods boards, and others who are familiar with neighborhoods and their needs on the ground.

Houston’s initial attempt at launching a citywide data strategy struggled. Menon, Houston’s first CDO, spent three years working on an open data portal and attempting to get a data strategy off the ground. The portal was built using open-source technology from local data science consultancy January Advisors. But soon after the portal’s launch, Menon moved on to become the Chief Information Officer for the City of College Station. (She is currently the Chief Information Officer for the City of Raleigh.) Not only did movement on any broader data reforms stall, but the City’s publication of open data and data-sharing with outside partners became an ad hoc and disorganized effort coordinated by remaining IT staff who are typically tasked with the more technical administration of the City’s internal systems.

CDOs in any city can face cultural and political barriers. For example, when department-level staff don’t want to adopt new workflows that require them to publish data, a city’s public data portal can remain static with old data for months or even years. This, in turn, affects the abilities of civic actors outside of government to work on improving social or political challenges. Broadly, governments work on long timelines, and the shift toward a data-driven or evidence-based culture of governing can take and has taken years to even be seen as a standard practice. Nonetheless, over 100 cities have passed open data policies and launched sustained open data programs. Meanwhile, efforts in Houston have slowed.

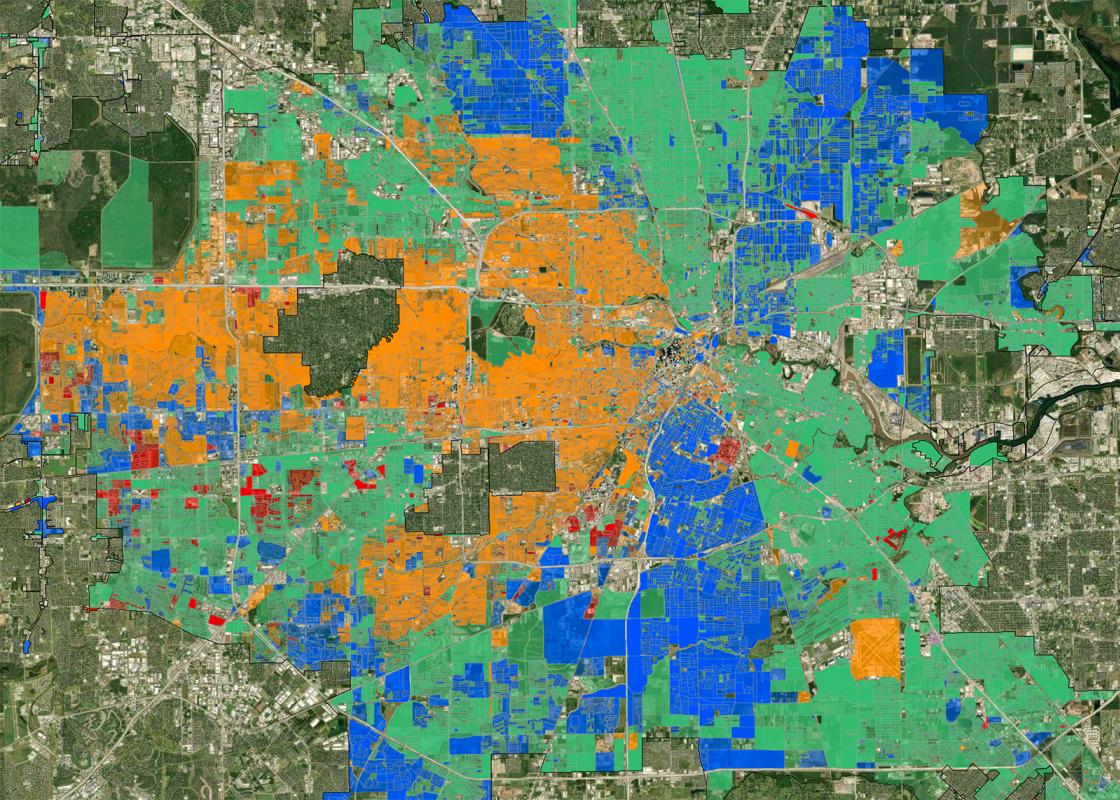

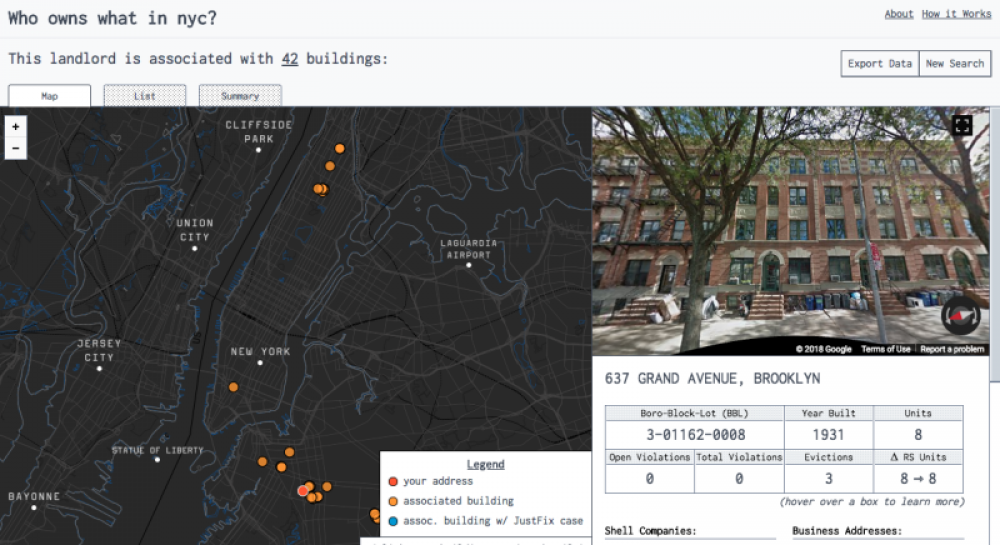

In the United States, an additional challenge is that the private sector hoards data. The real estate industry dominates the proprietary data market, where a single dataset on property values or parcel ownership can cost thousands of dollars to access. As a result, high-quality data on changes in the housing market are only available to developers or real estate agents at large corporations. This leaves people like tenants’ rights advocates or housing advocates working against gentrification out of the loop and reliant on public information sources to understand what is happening. Researchers, activists, and residents rely on governments—from the federal level on down—to publish public data which can inform collaborative solutions.

How might the new CDO be successful in Houston, where the culture of local government is distinctly pro-business and the largest community organizations have strong personal and financial ties to business lobbies?

The first priority must be investing in public capacity for data collection, governance, and use. Community organizations can benefit from deeper investment in community-owned data infrastructure, through funding for staff whose jobs are to collect and coordinate data use with other nonprofit partners, for example. And City departments need the same support for innovative data projects that improve public services, increase transparency, and inspire more participatory uses of public data.

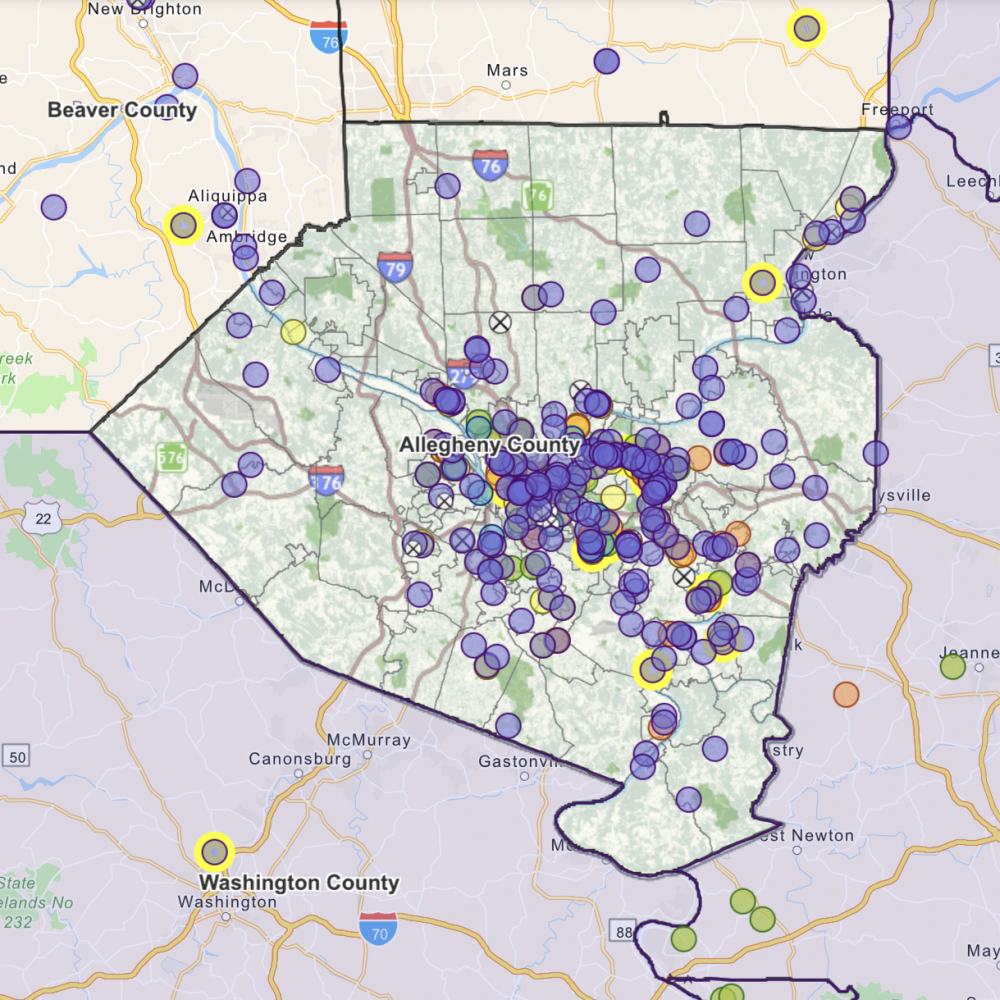

Compiling public data and making it useful is difficult work. As successful case studies, groups like the Housing Data Coalition in New York City have pooled their resources to create data tools like HeatSeek, which helps tenants submit requests for inspections when landlords fail to provide heat in the winter. In Pittsburgh, collaborative efforts like the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center bring together data from the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, and the University of Pittsburgh to make searchable property ownership databases and community asset maps open for public use.

In Houston, Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research does the fundamental work of openly publishing community indicators, but can’t go much further without support from the City and County to gain access to regularly updated, high-quality, large-scale datasets.

Today, Raphael Louvrier is Houston’s second Enterprise Data Officer (EDO). At City Hall, the EDO reports directly to the Mayor, who leads under Houston’s strong mayor system of government. Prior mayors have attempted to influence city council agendas and policy priorities. Central to Louvrier’s success will be his relationship with Mayor Turner, who can sideline projects he doesn’t see as a priority or advance others he favors, as he was accused of doing by former Director of Housing and Community Development Tom McCasland. Lessons from other cities and states show that CDOs need far-reaching executive authority to build out infrastructure that breaks silos across city departments and creates incentives for stronger cultures of data use.

Anyone who has worked with local government knows that getting departments to consistently talk to one another is the hardest part of any project requiring data. Data-sharing across departments can supercharge city operations but requires dedicated effort and reform. For example, the Planning & Development Department could begin sharing data with Houston Public Works and code enforcement officers to learn if they’re giving development permits to companies that have consistently failed code inspections. But to do so, data systems in both departments would need to be re-designed to talk to each other, and people would need to be trained on how to use and maintain those new systems.

Houston’s centralized innovation bottleneck has wider impacts beyond the City's own data and technology reforms. Many cities participate in national networks that help them push the envelope and incorporate new ideas in municipal governance; Houston is a dark spot in maps of cities that participate in these networks.

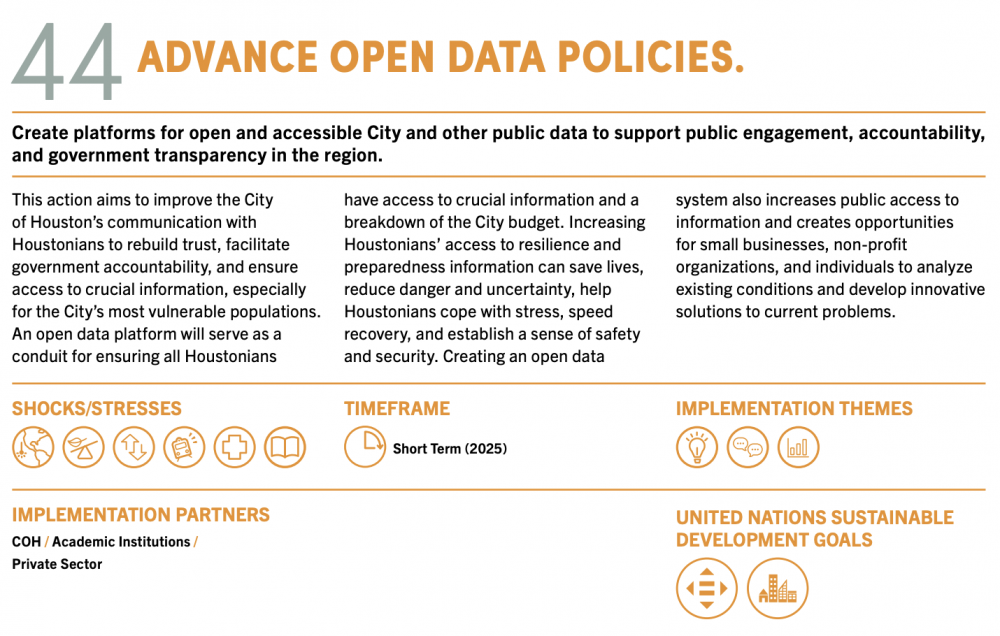

It’s not too late for the City to make improvements. With the support of local civic innovators who care about the improvement and use of public data, Houston can become a city that welcomes new ideas and applications of data and technology. (A platform for open data is Action 44 in the city’s Resilient Houston plan; its one year report lists the goal as "in progress.") As evictions across the county climb and flood risks grow with each hurricane season, activists and community members will need access to information that helps them coordinate their own responses to evolving crises. In his role as EDO at the City, Louvrier could commit to supporting these community users of public data as part of a new innovation agenda.

On August 11, the City’s open data portal was taken down for maintenance, perhaps in anticipation of Louvrier’s arrival, before being reinstated later that month. Louvrier, when approached for comment, said he was working on the City’s new data and analytics strategy and that mission of the City's IT Services Department “is to provide solutions that serve, protect, and enlighten Houstonians.” Louvrier said that despite recent natural disasters and the effects of the global pandemic, the City's Enterprise Data & Analytics Center will support the Houston hackathon, provide open data through a portal for researchers and organizations, listen to requests for additional data sets and present those to Data Governance Committees, and collaborate with local education institutions on selected subjects. Louvrier also referenced the stated goal of the Open Data Portal, which is to “encourage civic engagement and collaboration, improve transparency, and facilitate access to public information.”

Houston is ready for a new vision of innovation that actually serves communities, including by fulfilling all of the City’s promises around open data and data-sharing. Houstonians would benefit if Louvrier leads with a renewed commitment to stronger public data and technology resources that help residents build their future for themselves.

Katya Abazajian is an organizer, researcher, and writer helping communities and governments use data and technology to build better cities. She is a Fellow at the Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation where she leads state and local work on open government, civic technology, and data equity.