This article is part of a special series about preservation in Houston, edited by Helen Bechtel. The article was updated December 7, 2016.

In Dust Tracks on a Road, Zora Neale Hurston depicts her childhood in Eatonville, Florida — the first all-Black incorporated town in the United States — as both Edenic and rough. It is a story more about the will of a people to achieve self-determination than one of subjugation by a White majority. Communities like that of Eatonville were built across Texas, as well — streets, houses, shops, city halls, and parks built by former slaves and their descendants — in landscapes we routinely drive by without noticing.

“I didn’t know Independence Heights was the first African-American incorporated community in Texas until I was 40, even though I have family living in the community, and I grew up in the church in Independence Heights,” says Tanya Debose, a lead organizer of the Preserving Communities of Color Workshop, a national gathering and weeklong series that culminated November 19 in Houston. The four-day, multi-venued event attracted more than 150 participants including students from Prairie View University and MC Williams Middle School.

The workshop helped expand the tent of the historic preservation movement. Preservationists, in our imaginations, busy themselves saving classical buildings fronted by columns and Corinthian capitals. The reality has always been more complex, but there is truth to the perception of a movement dominated by White elites preserving a Eurocentric history. For example, less than one percent of the National Historic Landmarks are connected to Latino history. (See Sarah Zenaida Gould’s essay in Bending the Future.)

“I don’t think our ancestors were trying to make history,” says Debose. “They were trying to make a home and they went through a lot of stress. My drive comes from wanting to build on those legacies.”

That drive to preserve communities of color resonates across the United States and the African diaspora. The conference drew participants from across the country. Keynote speakers included leading preservationists like Brent Leggs, who was in Houston for the National Trust for Historic Preservation Conference.

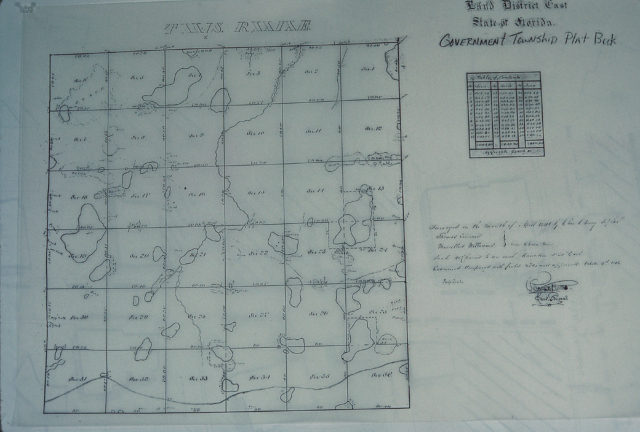

Bexar County, Texas road map, c.1890, identifying “Negro settlement” and “Baptist church." Photo: Everett L. Fly.

Bexar County, Texas road map, c.1890, identifying “Negro settlement” and “Baptist church." Photo: Everett L. Fly.

“It’s not just about the buildings,” said Suzanne Yowell of Partners for Sacred Spaces. “It’s about preserving the community, its people.” That means going beyond the built fabric and into the community: neighborhood churches saved by asset mapping (see Partners for Sacred Spaces), economic empowerment wrought by reciprocal business relationships (see Black Wall Street), creative place-making to attract people to the neighborhood (see Fifth Ward CRC).

“It is our responsibility as African-American preservationists to preserve our identity,” said Brent Leggs in his keynote to the conference.

The focus of the conference on Black settlements benefits from decades of work by Everett Fly to document and preserve African- and Native-American community sites. Based in San Antonio, Fly is a licensed architect and landscape architect who studied with J.B. Jackson at Harvard and is a recipient of a National Humanities Medal of Honor.

When Orange County, Florida, was planning to put a four-lane thoroughfare through Eatonville, Fly was brought in to do an independent assessment of the impact when the initial survey found nothing of significance.

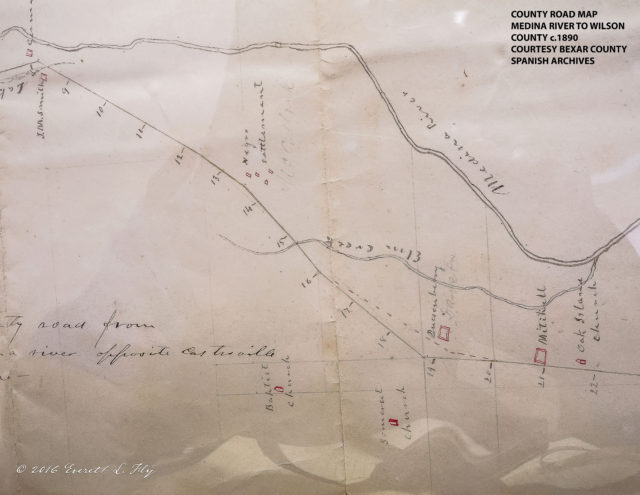

Mayor Ed Manuel of Pendleton, Alabama; Dr. Michelle Robinson of the University of Alabama; Tanya Debose of Independence Heights; Mayor Alberta McCrory of Hobson City, Alabama; Brent Leggs of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; Councilwoman Deneva Barnes, Hobson City, Alabama; Councilwoman Deborah Hattiesburg, Mississippi; Dr. Sade Turnipseed, Misissippi Valley State University; and Mayor Johnny Ford, Tuskegee, Alabama. Photo: Cheryl Joseph.

Mayor Ed Manuel of Pendleton, Alabama; Dr. Michelle Robinson of the University of Alabama; Tanya Debose of Independence Heights; Mayor Alberta McCrory of Hobson City, Alabama; Brent Leggs of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; Councilwoman Deneva Barnes, Hobson City, Alabama; Councilwoman Deborah Hattiesburg, Mississippi; Dr. Sade Turnipseed, Misissippi Valley State University; and Mayor Johnny Ford, Tuskegee, Alabama. Photo: Cheryl Joseph.

“I did my usual search for records,” Fly told Cite in a phone interview. “I found a map from the 1850s. The road through Eatonville was marked as an indigenous or Native American trail. The light bulb went off in my head. Zora Neale Hurston wrote about the role of the road in the cultural life of Eatonville. It is like [Henry David Thoreau’s] Walden Pond.” This connection and documentation not only stopped the road widening, it helped residents of Eatonville recognize their own cultural landscape and spurred the creation of the ZORA! Festival, which now draws more than 125,000 people annually, according to the festival website.

Tanya Debose sees Eatonville as a possible model for places in Houston like Fifth Ward, Independence Heights, and Borderville. The preservation and celebration of history, she argues, can go hand-in-hand with development that includes rather than displaces long-time residents. Managing change starts with memory. She says, “It is about renewing these communities both as cultural destinations and as places where people can afford to live.”

The social, political, and economic changes roiling our cities and towns appears to be driving a new urgency to this work.

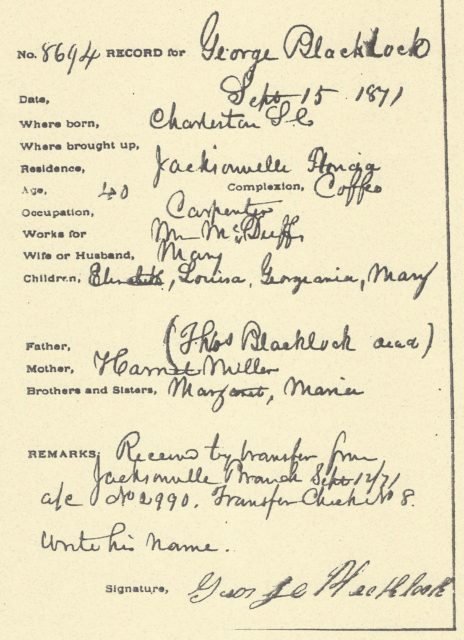

Document from the Freedman's Bank. Photo: Debra Blacklock-Sloan of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society - Houston.

Document from the Freedman's Bank. Photo: Debra Blacklock-Sloan of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society - Houston.Over 500 Black settlements across the state are threatened, according to presenters at the Preserving Communities of Color workshop. These sites include Freedmen’s Town near Houston’s Downtown and Riceville off of Gessner. The conveners and presenters at this past weekend’s Preserving Communities of Color workshop are fighting to preserve their communities by raising awareness of overlooked settlements.

Dr. Andrea Roberts, self-proclaimed activist researcher, said that “communities like Riceville weren’t necessarily platted, with boundaries on a map.” They were the product of post-Civil War squatting by recently freed African-Americans. These early settlers could claim ownership of squatted land if they were to make the land agriculturally, and therefore economically, viable. Local records, however, would not reflect their ownership claims, because a city courthouse in the late 1800s was not a welcome place to African-Americans trying to claim ownership. The undocumented land of these historical “Freedom Colonies” would eventually become unincorporated and annexed over time. Black land ownership has declined precipitously.

Houston’s newly reinvigorated preservation focus was tested these past few weeks with the displacing of historic bricks from Andrews Street in Freedmen’s Town. These bricks date to the settlement of the area by freed slaves after the Civil War. Residents of the “freedom colony” financed their own streets. Over a century later, with few original structures remaining and much of the African-American community displaced, the street itself has become a highly contested space with one activist placing her own body in the way of construction crews removing bricks. Mayor Turner recently announced plans to create a cultural district there.

The question that haunts Freedman’s Town is whether it is too late to carry out meaningful preservation of the buildings and community that called it home. Other parts of Houston, like Fifth Ward and Independence Heights, are more intact and have begun implementing plans to prevent displacement as new investment comes to streets like Lyons Avenue and North Main Street. Our own version of ZORA! Festival took place at the recent Sunday Streets along Lyons and can be enjoyed again at the Lyons Avenue Renaissance Festival, April 8, 2017. Along North Main, Rebuilding Together is partnering with the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council to carry out repairs and maintenance on 17 homes, a welcome center, a food pantry, and more in the historic center as part of the Superbowl Kickoff to Rebuild program.

“The [Preserving Communities of Color workshop] shows that the interest is there, the interest is real and authentic,” says Fly. “People are not coming just for the sake of nostalgia. People are coming to learn practical tools, ways to see and understand the places they live, and how to protect them. It is a major sign. The shift isn’t coming, it is already here.”