The Kelly Courts public housing community in Houston’s Fifth Ward (called Kelly Village since 1965) was named for Alex K. Kelley (1847-1928). Born enslaved in Brazoria County and an employee of the Southern Pacific Railway and its affiliates for much of his working life, Kelley also built and operated rental housing in Houston’s Fifth Ward. Early twentieth-century newspaper references make it clear that he was a respected civic leader in Houston’s African American community. [1] In their biographical profile of Kelley, historians Patricia Smith Prather and Bob Lee note that since 1940, when the board of commissioners of the Housing Authority of the City of Houston (HACH) adopted the recommendation of its “Negro advisory committee” and named its Fifth Ward complex for Kelley, his name has been misspelled. [2] This misprision is telling. It suggests the extent to which public housing communities in Houston don’t register as critical sites. If a name is consistently misspelled, then, by default, that becomes its received spelling, and this repeated error showcases its lack of importance to the speller. This passive aggressive approach to nomenclature reflects an official indifference to Kelley Courts matched in the twenty-first century by its increasing marginalization.

Kelley Courts was the second of four public housing complexes planned and built by the Housing Authority between 1938 and 1944. [3] Surveys of substandard housing conditions in Houston conducted in 1938 and 1940 revealed that the greatest need for housing was in African American neighborhoods. Therefore, the first two communities constructed by HACH were built for African American families: the first phase of Cuney Homes in Third Ward (1938-40) and the 344-unit Kelley Courts in Fifth Ward (1939-41). Both were designed by the Houston architectural firm of Stayton Nunn & Milton McGinty. John F. Staub was consulting architect and Hare & Hare of Kansas City were landscape architects. The R. F. Ball Construction Company of Fort Worth was general contractor for both communities. [4]

Nunn & McGinty followed the same design template at both Cuney Homes and Kelley Courts. Their reinforced concrete-framed residential blocks were configured as thin, two-story, flat-roofed bars. Every apartment occupied the full depth of the structure, so the two-story units had both front and back doors. The buildings’ thinness facilitated cross ventilation in Houston’s hot-humid climate. The end units were stacked one-floor, one-bedroom apartments. Interior partitions were hollow tile block or plaster on metal lath. Exterior walls were faced with dark red brick. Windows were steel casements. There were one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments. All came equipped with electricity, natural gas, running water, a stove, refrigerator, heaters, kitchen cabinets, closets, and a bathroom. Apartment blocks were raised several feet above grade; cantilevered concrete porch slabs and canopies marked the entrances to individual units. The buildings were spartan in their austerity. Even so, the Region VI office of the United States Housing Authority (USHA) in Fort Worth directed Nunn & McGinty to revise their design of Kelley Courts to reduce costs. [5] The first tenants moved-in in December 1941. [6] The first manager was Judson W. Robinson, the father and namesake of Houston’s first African American City Councilmember. [7]

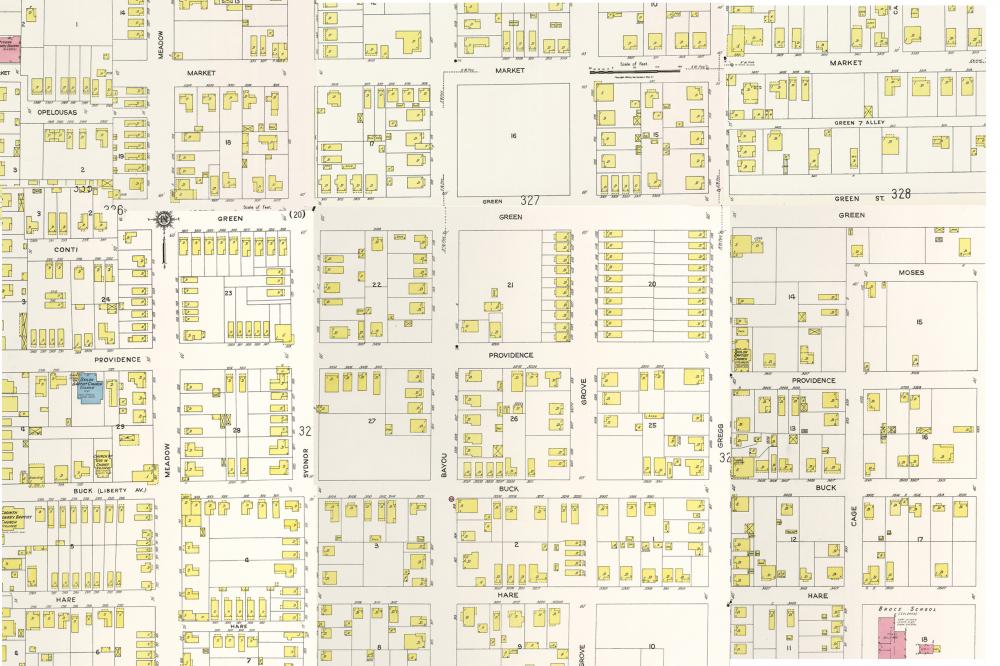

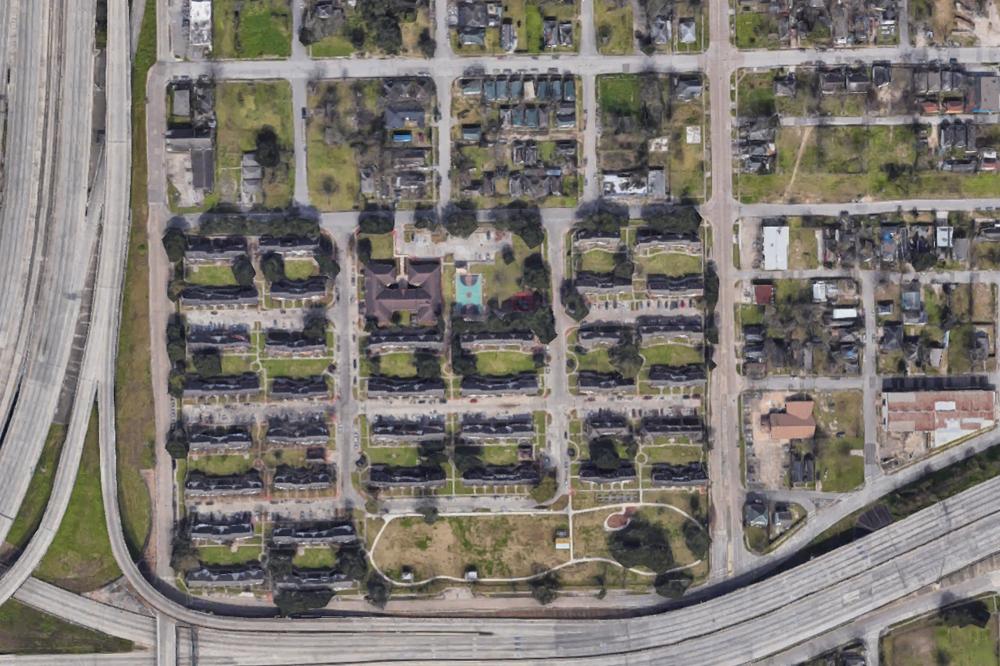

Kelley Courts occupied a 22.7-acre site in the Sydnor and Swiney Additions. During the summer of 1940 twelve blocks were cleared of 254 buildings, mostly small wood cottages, and consolidated into four “superblocks” served by wide, paved streets purposefully disconnected from the surrounding Fifth Ward street grid. [8] Kelley Courts’ long, thin buildings—sixty-one in all—were organized in eight parallel rows. The Sanborn fire insurance maps of Houston, which show the outlines of buildings on city blocks, display the contrast between the ordered rows of housing at Kelley Courts, evenly spaced to face continuous pedestrian corridors and rear service drives, and the dense, irregular fabric of surrounding city blocks, the “slums” that Kelley Courts displaced.

Today, the two-story wood M. Baglio corner store building at 920 Gregg Avenue is a rare survivor of the old Fifth Ward fabric. The visual and spatial contrast between Kelley Courts and its neighborhood setting was polemical: Kelley Courts was how the New Deal world of scientifically planned, professionally designed, durably constructed, and expertly managed housing for low-income families would be configured.

In June 1983, reporter Bill Minutaglio wrote a feature article on Lyons Avenue, “A Walk on the Baddest Street in Town,” in the Houston Chronicle’s Texas Magazine. [9] Minutaglio identified the strip of Gregg Avenue on the west edge of Kelley Courts as having been the location of The Bottom, where bars and clubs that did business after mainstream operations on Lyons Avenue shut down for the night, clustered. Minutaglio interviewed Constance Houston and Tracy Thompson, who lived two blocks north of Kelley Courts on Bayou Avenue. Houston’s grandfather, Joshua Houston, had been enslaved by the family of Margaret Lea Houston, Sam Houston’s wife. Mrs. Thompson’s memoir, Precious Memories of a Black Socialite, written with Dr. Naomi Ledé, recounted her career as a hostess and arbiter of manners. She represented a different facet of the culture of Fifth Ward than did The Bottom, the M. Baglio grocery, or Kelley Courts. The spatial conjunction of public housing, illicit entertainment, an immigrant-owned-and-occupied corner market, and decorous, heritage-conscious gentility bespeaks the layering of daily life in an African American neighborhood in a segregated Southern city during the twentieth century.

In 1951, construction began on the Eastex Freeway (U.S. 59), Houston’s second freeway. The dense fabric of Fifth Ward dissolved before the onslaught of modernization. Kelley Courts, once buried deep within Fifth Ward, suddenly stood exposed as the freeway grazed its western edge. [10] According to Houston freeway historian Erik Slotboom, the segment of the East Freeway (Interstate 10) between Wayside Drive and the Eastex Freeway was constructed between 1963 and 1966 adjacent to Kelley Courts. [11] Kelley Courts now sits in the elbow of the I-10/59 interchange. In order to construct the interchange, the Texas Highway Department exercised its power of eminent domain to acquire a 2-1/2-acre city park adjacent to Kelley Courts in 1970. [12]

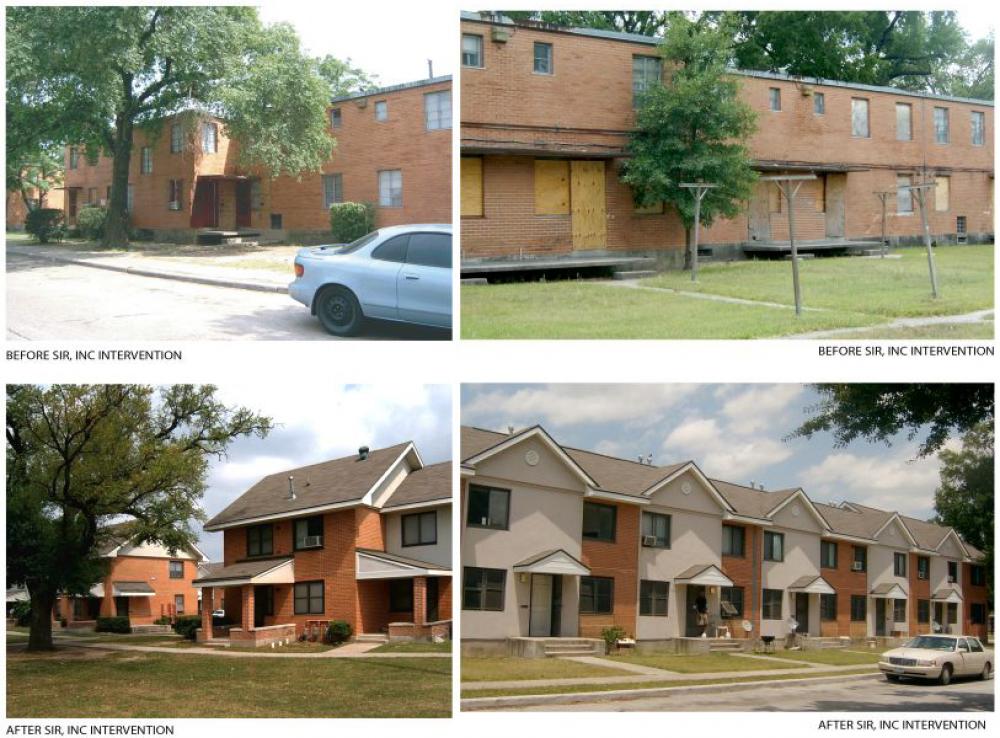

Kelley Courts has experienced two episodes of modernization: the first between 1985 and 1992, and the second beginning in 1997 and phased in successive stages through 2010. SIR Architects of Houston designed the interior reconstruction of apartment units and the application of stucco facades and pitched roofs that give “character” to Nunn & McGinty’s apartment blocks. [13] In 2009 the Houston Housing Authority (HHA) sought authorization to demolish eight buildings, containing sixty-three units, that were damaged during Hurricane Ike in 2008 and never repaired.

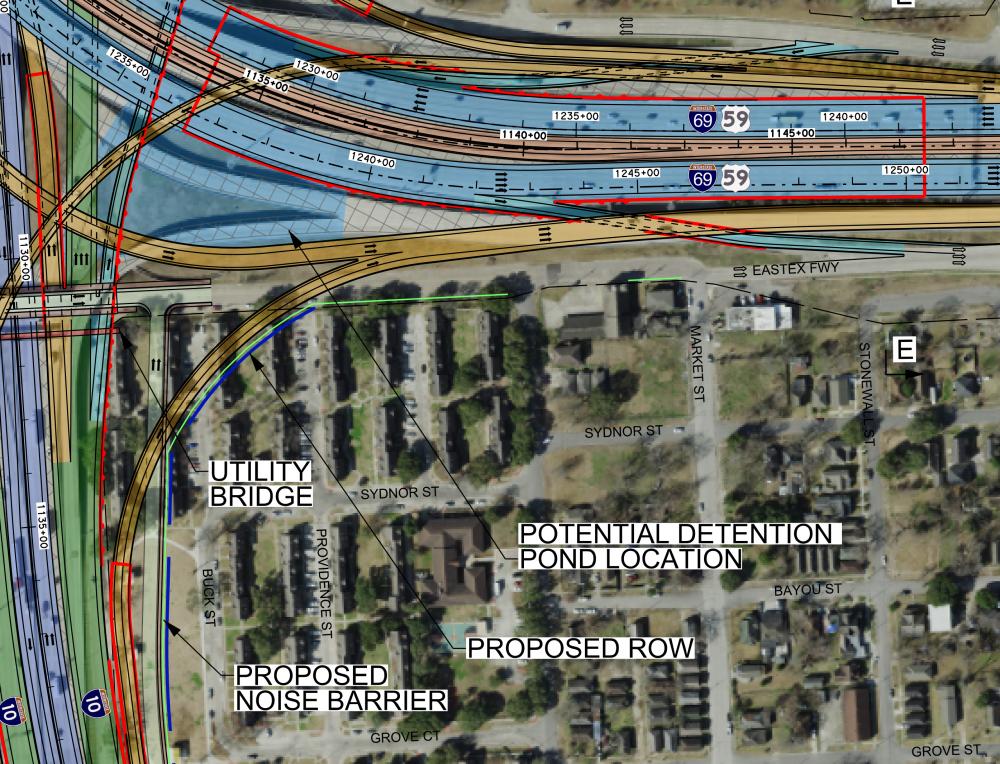

The newly vacant three-acre site, facing the East Freeway, was redeveloped as Kelley Village Community Park in 2015, based on designs by Asakura Robinson, landscape architects, and Brave/Architecture in collaboration with Val Glitsch, FAIA. As noted by LaRence Snowden, Chairman of the Board of Commissioners for HHA on Urban Edge, should the Texas Department of Transportation’s proposal for rerouting and expanding I-45 be constructed as proposed in 2019, the entire park and most of the western third of Kelley Courts, containing seventy-two of the community’s remaining 333 units, will be demolished and replaced by a new 10/45/59 interchange. [14]

Kelley Courts fares better in TxDOT’s plan than HHA’s Clayton Homes, less than a mile to the southwest, which could see all of its 296 units demolished to straighten I-45 as it crosses Buffalo Bayou. What stands out in this scenario is Kelley Courts’ irrelevance in the estimation of state agencies, policy makers, and highway engineers. These structures, in their eyes, exist without historical or cultural significance. Once Kelley Courts has been chipped away completely, will it matter that its name was misspelled?

Stephen Fox is an architectural historian and a Fellow of the Anchorage Foundation of Texas. He is a lecturer in architecture at Rice Architecture and the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design.

Notes

[1] “Project Indorsed (sic) by Voters of the Second Ward,” Houston Daily-Post, 1 November 1910, 3; “The Celebration Closed,” Houston Daily-Post, 20 June 1911, 18; “Emancipation Park Receiver Is Asked,” Houston Chronicle, 4 August 1911, 5; “Negroes Select Fifty Men To Preserve Peace,” Houston Daily-Post, 2 August 1919, 9; “Names for New Grand Jury Are Selected,” Houston Chronicle, 26 April 1924, 1; “May Be Klan Members But Haven’t Paid,” Houston Chronicle, 5 May 1924, 1; and “Negro, Former Slave, Leaves Rich Estate,” Houston Chronicle, 27 November 1928, 17.

[2] Patricia S. Prather, “Kelley, A. K.,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 06, 2020, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/kelley-a-k. Published by the Texas State Historical Association. “Negro Housing Center Named Kelly Courts: Project Will Be Located at Green and Gregg; Condemnation Suits Slated,” Houston Chronicle, 28 March 1940, A9; and “H. H. A. to Receive Picture of Kelley Courts Namesake,” Houston Post, 20 September 1942, 13.

[3] The Housing Authority of the City of Houston was chartered in early 1938 by the Houston City Council after the Texas Legislature passed enabling legislation in conformance with the Wagner-Stegall Act of 1937, authorized by the U.S. Congress, which established the United States Housing Authority (USHA) to administer public housing for low-income families throughout the country. The USHA provided loans to local housing authorities financing ninety percent of the cost of real estate acquisition, planning, design, and construction for public housing complexes built to USHA regulations on USHA-approved sites and managed according to USHA practices. The USHA also provided operating subsidies to local housing authorities should the rents they charged not cover their expenses. Local authorities were to pay down the bonds that financed construction over a sixty-year period. For every unit of new housing constructed, a unit of substandard housing had to be demolished (this was the “slum clearance” formula). Local housing authorities followed prevailing practices in racially segregating (or integrating) complexes.

[4] “Kelly Courts Contract Due on Wednesday,” Houston Chronicle, 30 June 1940, 7B. Architects Stayton Nunn and Milton McGinty had recently collaborated with the Washington, D. C. architect Oliver C. Winston (a Rice architecture graduate, like Nunn and McGinty) on the design of the River Oaks Shopping Center at W. Gray Avenue and S. Shepherd Drive (1937). Inasmuch as Winston had become regional director of the USHA by 1938 and, in that capacity consulted closely with the HACH’s board and staff, none of whom had any planning and construction experience, it seems likely that he steered the architectural commission to the firm. HACH’s other three complexes—the second phase of Cuney Homes, Irvington Courts, and San Felipe Courts (subsequently renamed Allen Parkway Village)—were designed by a consortium of eleven Houston architectural firms, indicating the political advisability of dividing the economic pie during the Depression decade.

[5] “Survey Will Be Made of Housing Here,” Houston Chronicle, 7 December 1939, 2B.

[6] “Forty Negro Families in New Project: 140 To Occupy Kelly Courts; Final Details Being Worked Out by Authority,” Houston Chronicle, 1 December 1941, 10A.

[7] “Negroes To Dedicate New Clinic Building,” Houston Chronicle, 24 November 1942, 18A.

[8] “Street Plans for Housing Sites Studied,” Houston Chronicle, 28 April 1939, 12B; “Bids for Clearing Site for Housing Job To Be Taken,” Houston Chronicle, 4 April 1940, 12A; “Bulk of Property for Negro Housing Obtained,” Houston Chronicle, 11 April 1940, 20A; “Contract Let to Wrecking Firm by Housing Agency,” Houston Chronicle, 6 June 1940, 1B; “Wrecking of Area for Negro Slum Project Started,” Houston Chronicle, 21 June 1940, 4C.

[9] Bill Minutaglio, “A Walk on the Baddest Street in Town,” Houston Chronicle Texas Magazine, 12 June 1983, 8-10, 19-21.

[10] “Expressway Job Awards Are Due Soon,” Houston Chronicle, 5 September 1950, 1; “Houston of Tomorrow,” Houston Chronicle, 24 February 1951, 7; Dick Yates, “City Due for Relief from Two Big Traffic Headaches,” Houston Chronicle, 31 August 1952, A17; “$3,000,000 Jensen Interchange,” Houston Chronicle, 14 April 1953, B1; and “A New Route to East Texas,” Houston Chronicle, 4 October 1954, A9.

[11] Slotboom, 236.

[12] “This Park Must Go,” Houston Chronicle, 13 August 1970, Section 1, 10.

[13] Carlos Byars, “Face Lift for Irvington Village / Officials, Residents Unite To Come Up With the Best Renovation Plan” Houston Chronicle, 28 April 1997, 15A.

[14] Dug Begley, “Massive I-45 Project Will Remake Houston Freeway Spine, But at What Cost?” Houston Chronicle, 14 June 2019, A1, 13; Dug Begley, “TxDOT’s $7 Billion Plan to Shorten Your I-45 Commute May Displace Hundreds of Families,” Houston Chronicle, 4 June 2020; and LaRence Snowden, “How the I-45 Project Will Affect Two Affordable Housing Communities,” Kinder Institute Urban Edge, 19 June 2019, https://kinder.rice.edu/urbanedge/2019/06/18/how-i-45-project-will-affect-two-affordable-housing-communities.