Stephen Fox is an architectural historian, fellow of the Anchorage Foundation, and lecturer at Rice and the University of Houston. His books include AIA Houston Architectural Guide and The Country Houses of John F. Staub.

Robert Venturi was a singular figure in the history of late twentieth-century architecture. Although best-known for launching the postmodern critique of architectural modernism in the 1960s, Venturi pursued a highly personal investigation of phenomena that he discerned in historic buildings and sought to reproduce in buildings constituted by modern programs and built on modern sites using modern techniques, which was the premise of his first book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.

His efforts to spatialize figures of rhetoric --- to construct, for instance, spaces that one experiences as “ironic” --- stand out, as does his investigation of surface and space, flatness and shallowness, color and pattern, without articulating construction as modern architects were taught to do. Venturi was so radical, and his critique so disruptive, that the American architectural profession basically never forgave him. Even the honors he eventually received --- fellowship in the American Institute of Architects, a Pritzker prize --- were controversial and contested, indicative of how profoundly unsettling his vision of architecture proved to be.

His Philadelphia-based firm, Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, designed three Houston projects: the Park Regency Terrace Residences (1983) at 2333 Bering Drive, the Children’s Museum of Houston (1992) at 1500 Binz Avenue, and a pair of houses, the Habitat for Humanity Demonstration Houses (1999) at 2901 Gillespie Street in Fifth Ward, built by Drexel Turner and architecture students at the University of Houston.

Habitat for Humanity Demonstration Houses (1999) at 2901 Gillespie Street in Fifth Ward. Photo: Hester + Hardaway.

Habitat for Humanity Demonstration Houses (1999) at 2901 Gillespie Street in Fifth Ward. Photo: Hester + Hardaway.

The Habitat for Humanity houses represent Venturi, Scott Brown's social vision: they are marvels of spatial intelligence and generosity compressed into an 800-square-foot footprint.

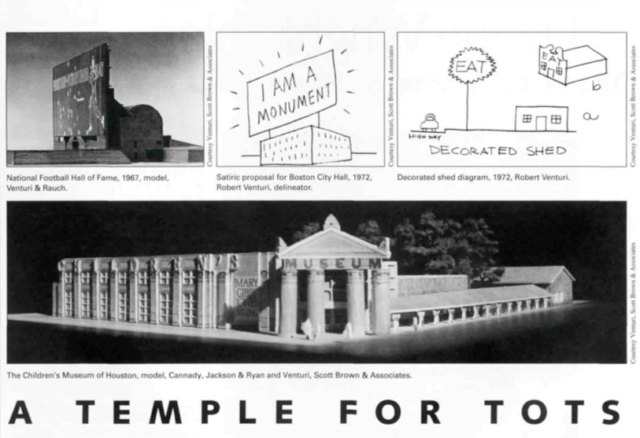

The Children’s Museum, in whose design the firm’s third partner, Steven Izenour, was involved, displays the tropes proposed by Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Izenour to characterize American popular architecture in their jointly authored book, Learning from Las Vegas. The museum is part “duck” (a show-off building) and part “decorated shed” (a pragmatic building that relies on minimal applied decoration to pretend to be architecture). The mock classical entrance portal and the “caryakids” (the columns holding up the bus drop-off canopy on the Crawford Street side of the museum) materialize Venturi’s fondness for translating word play into architecture and his conviction that wit is an important value in architecture.

Lead images from 1991 Cite article on Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates plans for The Children's Museum of Houston.

Lead images from 1991 Cite article on Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates plans for The Children's Museum of Houston.

Venturi consistently undermined the masculinist pretensions of 1960s American modernism. His architectural preference for indirectness, weakness, and “inflection” --- rather than boldness, strength, and assertivenes --- stands out. In this respect, his critique can be likened to that of his contemporary, Andy Warhol. Both demolished the heroic aspirations of their modernist peers through subversive humor. What set Venturi apart from stylistic postmodernists --- Philip Johnson --- and theoretical postmodernists --- Peter Eisenman --- was his extraordinary architectural imagination. Venturi thought, saw, and drew on an original set of precepts, both rhetorical and architectural, that caused his firm’s buildings to stand out as exceptional, even, on occasion, disturbing, but always powerfully memorable.

Further Reading from Cite on Robert Venturi

Kaliski, John. "Diagrams of Ritual and Experience." Cite 3. Spring 1983.

Peters, Patrick. "A Temple for Tots." Cite 26. Spring 1991.

Turner, Drexel. "Little Caeser's Palace: The Children's Museum of Houston." Cite 30. Spring-Summer 1993.

Barna, Joel Warren. "Back in the Saddle: Venturi Scott Brown's Austin Museum of Art." Cite 31. Winter-Spring 1994.

Grenader, Nonya. "The (small) House." Cite 54. Summer 2002.