Sturdy books about Houston’s built environment are few and far between. Perhaps one of the few positive aspects of this dumpster fire of a year is the arrival of two new works about the history of Houston and the future for Houstonians. Improbable Metropolis by Barrie Scardino Bradley and Prophetic City by Stephen Klineberg show us what Houston has been and what Houston will be, respectively. While the first publication looks back to illustrate what we’ve built here since 1837, the second anticipates where we’re going.

Improbable Metropolis

Barrie Scardino Bradley is an accomplished historian who has written extensively about Houston's architectural history. Beginning in 1979, she has consistently produced this history, at first for Rice through the realization of her Houston Architectural Survey and then as the Architectural Archivist at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center, a preservation consultant, independent scholar, and Executive Director of AIA Houston. Bradley was also Editor of Cite from 1996-8.

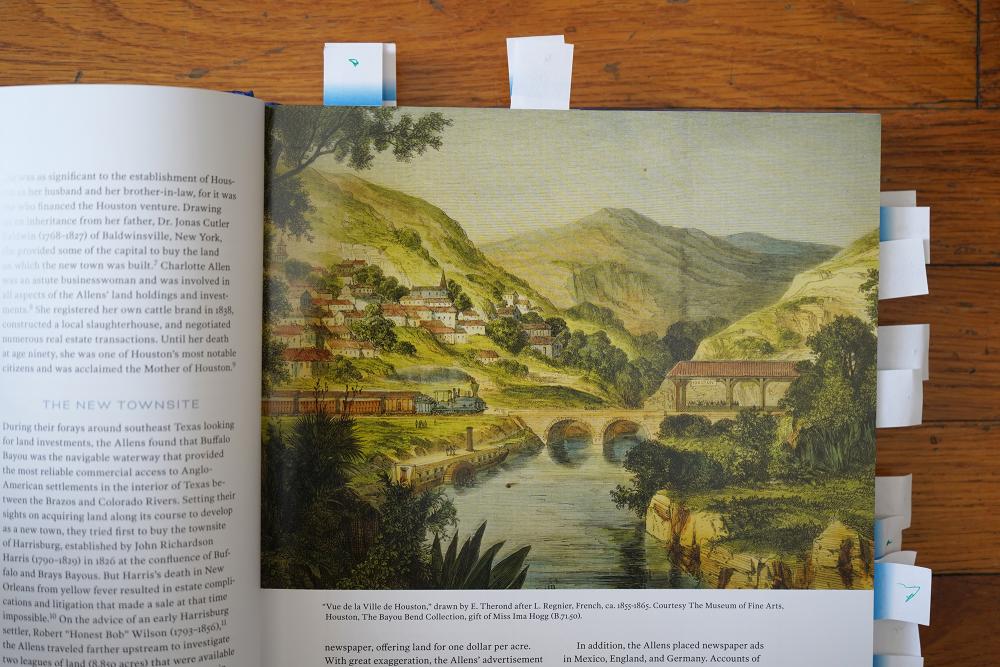

Improbable Metropolis, published by the University of Texas Press, tells the story of Houston through its buildings and places. Beginning from E. Therond’s misleading sketch Vue de la Ville Houston—an advertisement that depicted Houston as a quaint settlement in a steep valley along a picturesque river—the story of Houston unfolds through the examination of individual buildings and projects. Bradley conveys this history in an even and accessible writing style. The presentation is dry and stately, in the style of historian Stephen Fox, with whom Bradley has worked closely on many projects and to whom this new book is dedicated.

Bradley’s work is organized chronologically using a sequence of nicknames that describe the phases of the region’s development from Bayou City (1830-65) to Petro Metro (2000-17). The city’s mercantile nature is a particular fascination: In its early years as a growing center, Houston largely relied on transit (the railroad and the port) to bring materials, ideas, and people to the city. The same is true of its architects, who arrived from elsewhere to practice their trade. The book provides good accounts of the work of late nineteenth century architects Eugene Heiner and George Dickey, whose careers flourished amidst the eclecticism of the era before the more sober forms of the Progressive movement, along with its reformations, took hold. History showcases how recent the profession of architect is: In 1880-1, the Houston City Directory only listed three architects—those two and Edward Duhamel.

Houston, as we know, exploded in size and importance in the 20th century, and the majority of this book focuses on the exponential growth of that time. Bradley chronicles the dizzying number of buildings, developments, and plans with clarity. Wealth from the oil industry enabled massive changes in both the infrastructure of Houston’s port but also in the realization of private developments, headquarters, and philanthropic achievements. The rise of major real estate players like Jesse H. Jones and their shaping of the city is central to the story of Houston. In the Space City chapter, Bradley shows the Houston Center project, which would’ve ganged thirty-three blocks downtown into a “city within a city,” designed by William L. Pereira and Associates; for better or worse only the first building was realized.

This history continues right up to the present day. Bradley includes major works of the 21st century, balancing scales between notable single-family homes and large urban initiatives like parks. At the close of each chapter, dedicated stories appear in blue boxes about topics that transcend the bounded timelines of the segment—some topics are Houston’s wards, public housing, structures of the energy economy, and New Urbanism. While redlining isn’t mentioned, Bradley addresses segregation through deed restrictions and recognizes notable work by Black architects, including Dallas-based W. Sydney Pittman and Houston’s own John S. Chase. She also includes architecture from many religious faiths through featuring Hindu and Taoist temples, Buddhist centers, and mosques. These projects are not often thought of as images of Houston, but they’re here and showcase the diversity of our region.

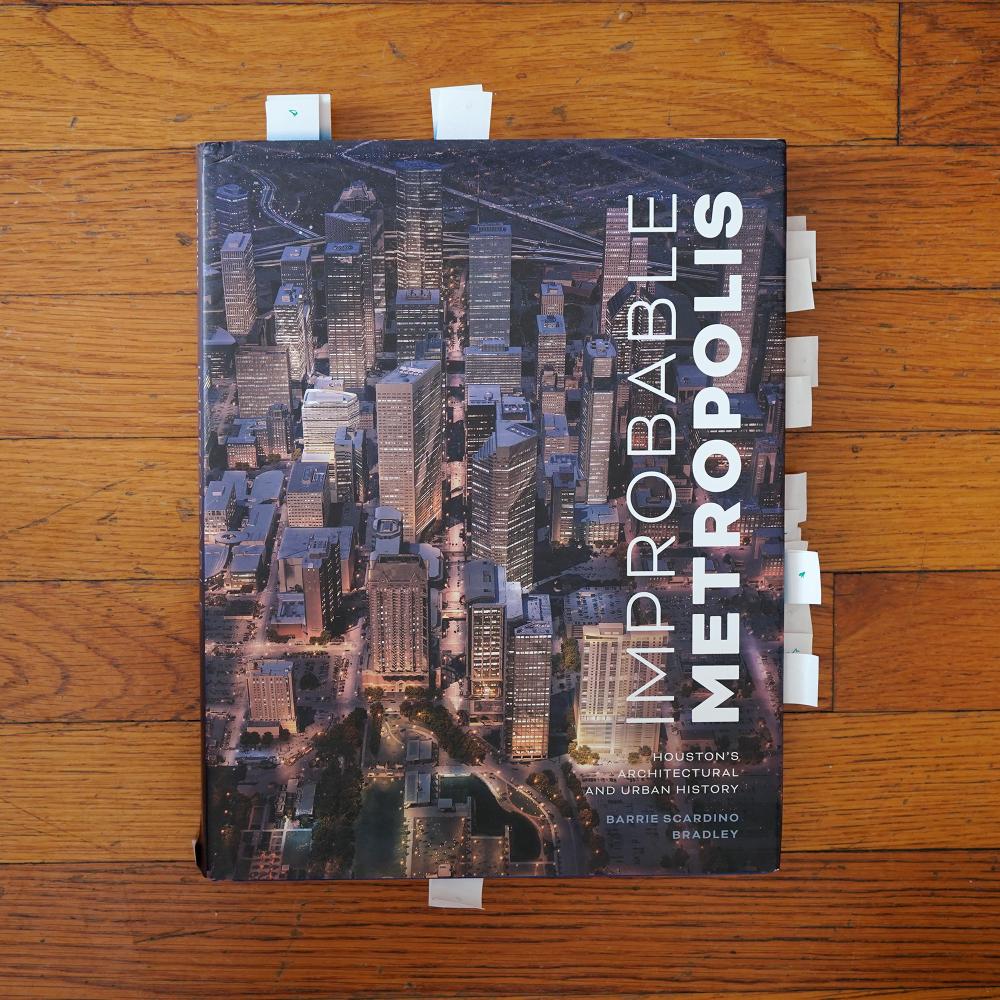

Improbable Metropolis is a visual treat. As Larry Lander noted in a Friday Reads entry about the book for RDA’s Instagram, the book object would hold its own on any Houstonian’s coffee table. Its page size is generous and gives the many color images and photographs space to come alive. Bradley’s archival expertise is on display to great success, with many large drawings, images, and photographs sequenced to powerfully communicate historic buildings and environments. Many of the images are the author’s, taken recently. Photography is important because so much of the city has been demolished, leaving its built history to only be seen in pictures and not in real life.

It’s appropriate, then, that the final image—and the book’s cover—is an illustration of downtown from Ziegler Cooper Architects. It merges the city’s historic thirst for speculative development with the pride of place that has blossomed lately like jasmine in spring. Bradley closes by admonishing the city for avoiding planning for so long. It makes economic sense to build back better rather than continuing to poorly rebuild after hurricanes. Bradley rightfully champions resilience as one of the city’s great qualities. When reaching our bicentennial, we should be able to look back and see that after Harvey, Houston emerged as a “stronger, more beautiful, and more equitable city,” she writes. As shown in Improbable Metropolis, Houston has leaned forward into the future for nearly two hundred years—now is no time to stop.

Prophetic City

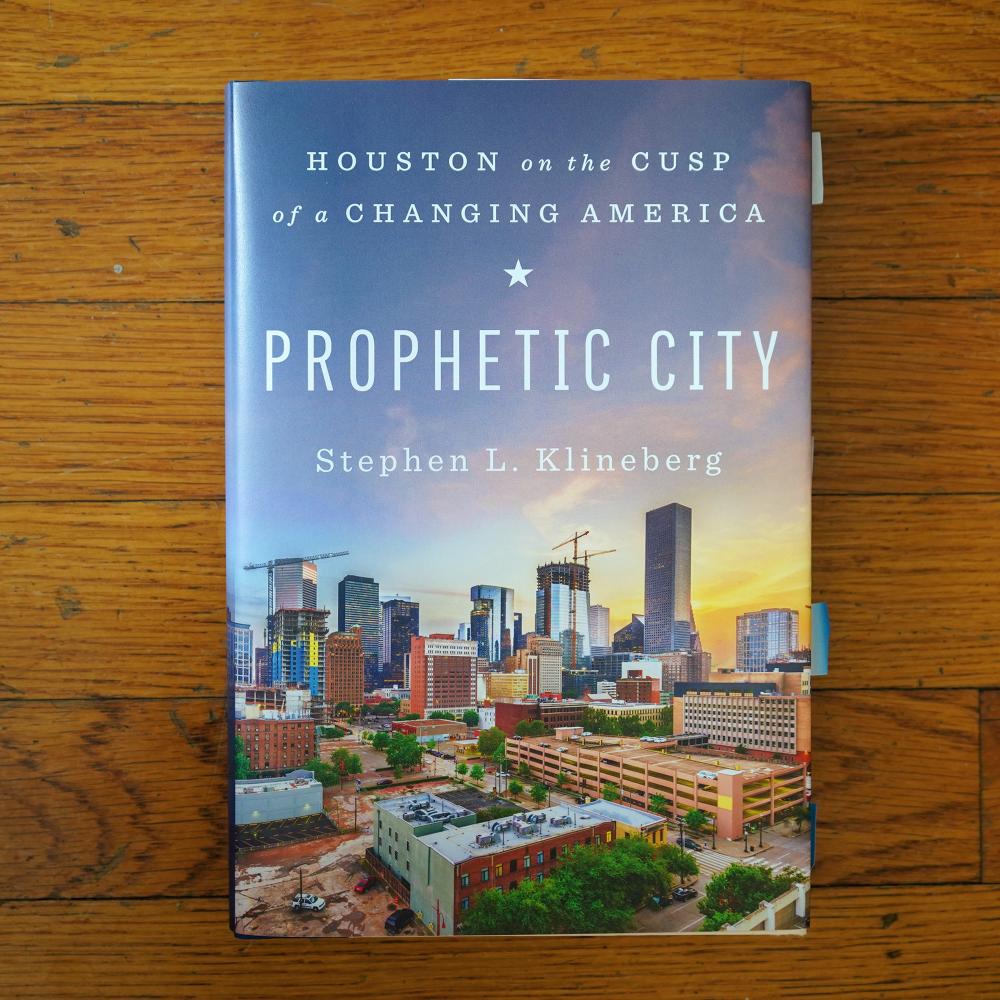

Stephen L. Klineberg is a Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Rice University and the Founding Director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research. Since the early 1980s, he has, with students, conducted a survey of Houstonians to poll their positions on a variety of topics. This research, now called the Kinder Houston Area Survey, showcases the demographic changes of this region using data to make the case. Klineberg’s recent book Prophetic City, published by Avid Reader Press, presents this research and its key findings in a straightforward and encouraging text.

Prophetic City claims that Houston shows us what America will be like in the 21st century. Much like Lawrence Wright’s investigations for The New Yorker, Klineberg trumpets that Texas is the future, and that Houston is the epicenter of this future-making. This is largely the result of demographics: In 2010, Harris County was 41% Hispanic, 33% Anglo (white), 18% African American, and 8% Asian. Klineberg is crystal clear about what is in motion:

The demographic transformation is a done deal. You can close the border, seal off America, build an impenetrable wall, and deport all ten million people who are here without the proper papers; none of those efforts will make much of a difference. No conceivable force will stop Houston or Texas or America from becoming more Asian, more African American, more Hispanic, and less Anglo as the twenty-first century unfolds.

Diversity is a selling point for Houston, but this doesn’t sit well with some, and Klineberg addresses that feedback. Unfortunately, this change is a major motivation for recent conservative politics, which has been practiced in ugly and divisive ways. If it hasn’t already, the growing ethnic plurality of contemporary America will reshape our images of who Americans are in the decades to come. Immigration remains a key part of our city’s puzzle: If Houston wasn’t such a welcoming destination or an economic powerhouse, the city would have lost population like many other industrial cities. This isn’t cause for celebration but the reason for stronger action; Klineberg writes that we need to move from “the idea of diversity to actual pluralism.”

The data, mined from decades of surveys, is unpacked in fascinating ways and presented in focused chapters. Klineberg goes through the cyclical boom-and-bust rollercoaster of Houston’s economic productivity, the shortcomings of our public education system, and our religious beliefs. In direct language, he addresses the deep history of segregation and racism in the city. In another chapter, he presents the conditions for Hispanic residents, including the differences that can be seen based on country of origin for immigrants and levels of education between generations.

The book is also a self-mythology: Klineberg is able to tell not only the story of the data, but his story of arriving to Houston and starting the Houston Area Survey in 1982 (the same year that Cite began). Famous Houstonians amble in and out of the tale, giving their advice. Klineberg is granted access to the office suites, boardrooms, and private tables where power has accumulated. A select number of average citizens appear to share also, with humbling results. He writes about the struggles faced and the insights gained and backs up these stories with the survey results. These findings are described in text and communicated using bar graphs. More and better visualizations would have aided this visual thinker, but the points still land.

Prophetic City also addresses our outdoor spaces. While there are many parks to champion, along with the expansion of the Bayou Greenways project, Klineberg notes that we also face a serious air quality problem. Houston is the most polluted metropolitan area in America. This must change. With some of work led by Mayor Turner—including Houston’s Climate Action Plan—there is light at the end of the tunnel, but no major movement. “Houston makes every bad, toxic thing in the world,” Jim Blackburn says in the book. “We have to have a plan other than letting it run till it can’t run anymore.”

The two biggest problems standing in the way of Houston’s future are education and class divisions, Klineberg declares. He writes: “The only way to build a successful and equitable multiethnic society is to ensure that all the members of the rising generation in all of our communities have a reasonable chance to acquire the educational credentials and technical skills that today’s economy requires.” Earlier on, he states that “the most compelling question for the Houston[ian] (and the American) future lies in the interconnection of ethnicity, age, and access to good schools.” In Prophetic City he makes this claim in a variety of compelling ways. If you’re looking to understand the challenges our city faces, you should read this book.

Houston has always suffered from an image problem, either a false image (it wasn’t a cowboy town!), many endlessly generic images, or no image at all. “The lack of a strong self-image is Houston’s biggest weakness,” offered Peter Marzio, former director of the MFAH, during a 2002 profile in Texas Monthly. What could the city look like in the future? Klineberg paints us a picture:

Beneath the gridlock of American politics and obscured by the overheated rhetoric in mainstream culture, individuals of all ages have been working quietly and effectively to develop more just and inclusive communities. Houston-area residents, at the forefront of these transformations, are called on to build something that has never before existed in human history—a truly successful, equitable, inclusive, and united multiethnic society, positioned for prosperity in the global, knowledge-based economy of the twenty-first century.

Now that’s a strong self-image! America in 2050 will look like Houston today. But where will Houston be in thirty years? As a city, we can lead the way, but not without the “needed investments in educational opportunities and social support systems,” as Klineberg writes. These are the first steps towards “sustainable prosperity,” an oxymoronic term that contains within its MBA-speak a core idea of spreading the wealth. If Houston can do anything, let’s do this.

Jack Murphy is Editor of Cite.