The changing requirements of educational space are just one part of the crisis we face as a result of COVID-19. In the third in a series of articles about COVID-19 and educational space, the authors write about designing flexible learning environments for inquiry-based learning and career and technical education. Read Part One, “Changing Paradigms in Educational Space,” here. Read Part Two, “COVID-19 Offers an Opportunity to Right Inequities in Education,” here.

In a 2010 speech titled “Changing Educational Paradigms,” Sir Ken Robinson poses a basic societal question: “How do we educate our children to take their place in the economies of the 21st century, given that we can’t anticipate what the economy will look like at the end of next week?” It’s a simple but powerful question that looms over our current educational system—a system, as Robinson explains, which “was designed, conceived[,] and structured for a different age […] in the economic circumstances of the Industrial Revolution.” The goal then was to prepare students for factory jobs.

While students today no longer need to memorize content, they do need to know how to think critically and ask the right questions; identify their passions and adapt them to changing circumstances; and appropriately find and use information to generate ideas and solutions that address the complex challenges of our world. The educational concepts of Inquiry-Based Learning and Career and Technical Education allow learners to own their learning and pave their way based on their unique strengths and passions.

Inquiry-Based Learning

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is an instructional framework that starts with developing a sense of wonder in learners by formulating questions, challenge statements, or problem scenarios. It requires learners to identify their curiosities related to the main question or challenge, to plan and conduct research, and to develop evidence-based solutions. By allowing learners to determine their personal interests and orchestrate investigations, IBL relies on the learner to grow through uncovering their passions. The more learners are driven by their interests, the more engaged and motivated they are in their learning and the more they develop a deeper understanding of subjects and topics.

In IBL, agency shifts from the educator to the learner and, therefore, changes the fundamental role of the educator. Rather than being keepers and distributors of knowledge, the role of the educator changes to that of a facilitator of learning experiences who engages learners by letting them own their learning journey. This process allows learners to become designers, builders, engineers, and artists as they solve problems, think critically, and develop skills for lifelong learning. When learners are working on a challenge, their exploration is not limited to one subject area. IBL is intentionally cross-disciplinary.

Career and Technical Education

Career and Technical Education (CTE) refers to a learning approach in which theoretical knowledge informs real-world applications. This approach, when aligned with challenging academic standards, develops technical knowledge and skills, applied sciences and technology, and modern career preparation. This type of learning is invaluable in today’s educational landscape as it serves as a direct link between curriculum requirements and both college expectations and workforce demand.

CTE benefits learners of all ages. Early and consistent exposure to a wide variety of career ideas and options builds connections in real-world contexts. CTE courses motivate learners to get involved in their learning by engaging them in problem-solving activities, collaborative team projects, and creating or constructing solutions. At the secondary level, CTE programs offer a significant advantage, as they provide learners the ability to “test drive” their interests before committing to a career or trade after high school. In a recent online survey, 87% of adults surveyed agree that the U.S. needs more CTE programs to prepare students for the jobs of today and tomorrow.

Today’s CTE programs offer hundreds of options for learners in an impressively large number of different fields. The National Career Clusters Framework, for example, includes sixteen Career Clusters, which include over seventy-nine Career Pathways which learners can pursue during their secondary education. These programs differ from traditional vocational programs of the past because they allow learners to graduate with college credits thanks to dual-enrollment capabilities with colleges and universities. A substantial number of CTE programs are also realized in partnership with industry, which means that graduates can emerge with professional certificates and gain experience in real businesses during their education.

Additionally, CTE programs do not discriminate against or create segregation among learners who are thinking about pursuing a college education and learners who are considering skilled labor jobs. Throughout history, vocational education presented itself as the path for learners who were “non-college-material,” which repelled a large portion of learner populations. Today, CTE programs are helping to create equity in education by bringing all kinds of learners to the table to make visible the workforce opportunities that they have, regardless of if that path takes them through college or not.

IBL and CTE as Economic Drivers

IBL and CTE are critical not just because they encourage learners to discover their passions, experience real-world application, and create more equity in schools; these models are also massive economic drivers for our society. Engaged learners stay in school. It’s projected that our economy will see an estimated lifetime gain of $168 billion dollars from reducing the high school dropout rate. More impressive is the statistic that 6 in 10 students plan to pursue a career related to the CTE area they are exploring in high school. Not only are learners staying in school at a higher rate, but they are going into the fields they study in high school. These instructional approaches are ensuring that more people are graduating with the ability to have a job and contribute to society. Through intentionally exposing learners to fields, industries, and jobs they might not have otherwise encountered, gaps in workforce are filled. Industries and businesses see a direct return on their investment of time and resources when they choose to partner with CTE programs.

Community colleges and universities are experiencing the economic benefit of both IBL and CTE programs. There’s a growing number of examples of K-12 schools sharing resources and facilities with higher education institutions. By fostering dual-credit opportunities, community colleges are seeing more learners enrolling directly after high school. This has economic importance, since it is estimated that community colleges alone add an estimated $800 billion to the U.S. economy. Broad stakeholder engagement is imperative when planning these programs to identify and respond to the needs and resources available in the community. West-MEC (Western Maricopa Education Center) in Phoenix is an example of a successful partnership between secondary and higher education, industry, and community. By blending the goals and resources of twelve school districts, local business and industry partners, and a community college, the multiple campuses, designed by DLR Group, allows high school students, college students, and adult learners to earn college credits in fields that meet local industry demands.

A New Learning Environment

Rather than imposing strict, linear progressions of learning, both IBL and CTE encourage learning through self-guided exploration. To foster this type of learning, the environment in which learning takes place must motivate, challenge, and inspire inquiry. The academic, social, emotional, community, and physical dimensions of the environment must all be considered when creating the best possible learning experiences. When designing the physical spaces, three strategies rise to the top to support engaging, hands-on learning: increasing awareness of engagement opportunities, removing barriers to authentic learning, and providing short- and long-term spatial flexibility.

As an example, consider the design of Sterling Aviation High School in Houston, designed by Stantec. Imagine walking into the main entrance of a school and immediately seeing a double-height hangar with multiple planes. Further into the school, you see students operating flight simulators and working in a large engine repair shop. The facility’s organization ensures that each student, parent, and community member can see the opportunities available within their school. The location of active, hands-on learning spaces at the heart of the school assigns an elevated value to those learning activities. Ample transparency and aviation-themed graphics reinforce the academic offerings while also connecting the school community to a common goal of providing each student opportunities beyond high school.

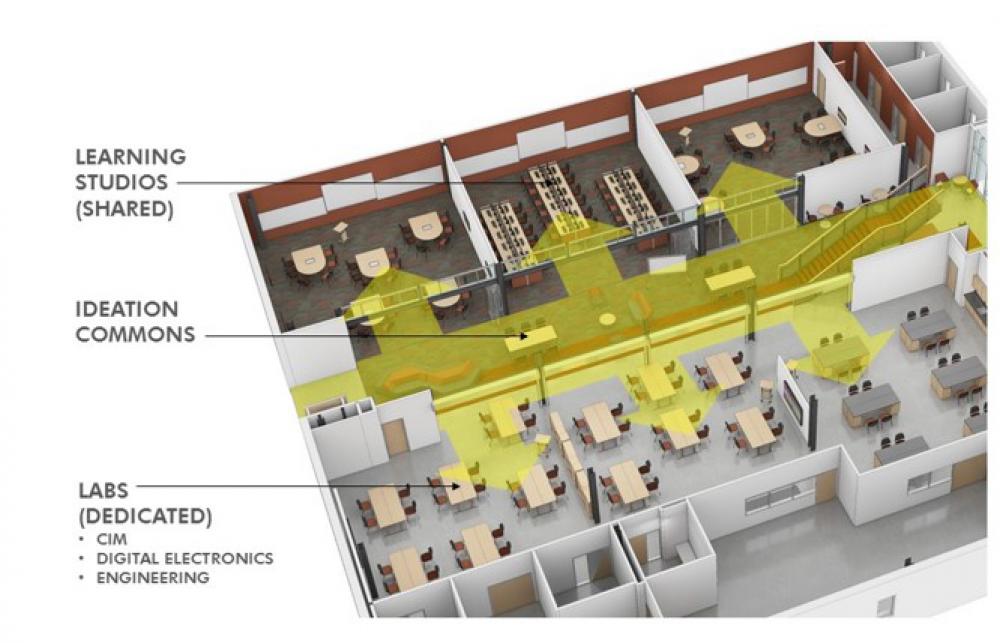

Non-traditional architectural adjacencies can break down the past hierarchy of college-bound and technical trade programs. When DLR Group designed the Cherry Creek Innovation Campus, Dr. Harry Bull, former superintendent of Cherry Creek School District, challenged the architectural team to inspire students the moment they entered the building. He shared this with our team: “Rather than thinking narrowly about participating in one pathway, we wanted students to see the possibility of creating their own trajectory through multiple pathways to meet their career exploration needs.” The intentional location of spaces that support a range of course offerings close to each other allows for multiple levels of collaboration, ranging from casual to intense. Human interaction and incidental pathways created by a shared commons space was pivotal in the overall planning and design. Fluid, bright, and open spaces immerse students into an environment that encourages exploration.

Importantly, some research predicts that Generation Z will have eighteen jobs over six careers over their lifetimes. Spaces designed today must last for generations of learners and, therefore, survive a multitude of changes in courses, tools, and resources.

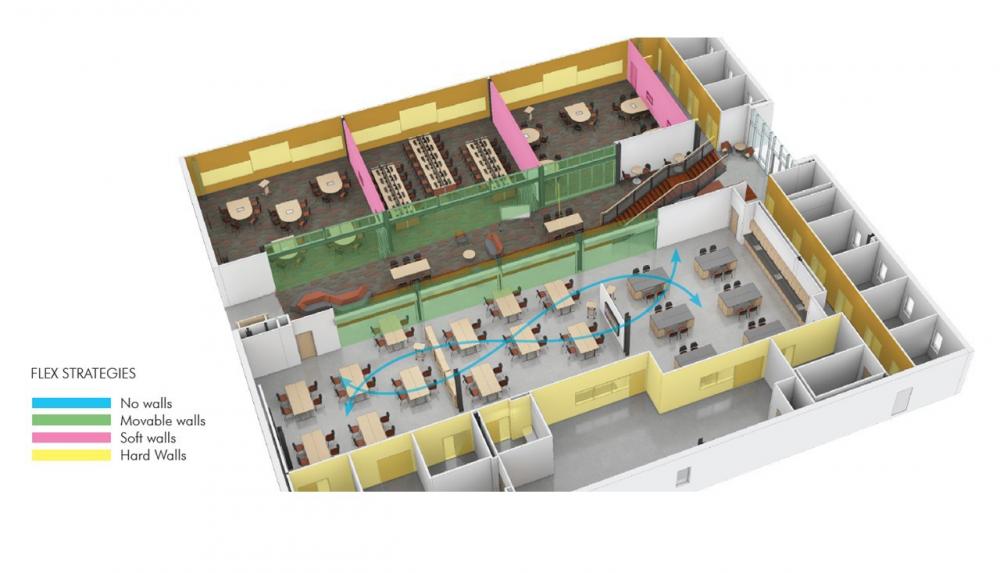

Spaces that support CTE learning can be thought of as tenant lease space with extensive utilities and support spaces. In the Missouri Innovation Campus, designed by DLR Group, the designers identified three types of walls—hard, moveable, and soft. The first is intended to stay in place for the life of the building and is constructed of concrete masonry units. The second is intended to move and adjust as needed for daily changes in learning activities. These space dividers consist of a variety of operable partitions and overhead, roll-down grilles. The soft walls are intended to change over time much like a tenant space might shift based on the needs of the company. They are constructed of light gauge framing, gypsum board, and have no electrical or other utilities located within. A facilities department could do light construction over a summer to rearrange space to support a new course offering. Additionally, spaces that require specialized equipment with varying electrical loads and compressed air or gas can be approached on a modular system.

The Janelia Research Campus and UT Health Science Center at San Antonio, both designed by Rafael Viñoly Architects, are examples of the modular planning that most commercial or higher-education science research labs utilize. These designs are based on the optimal depth of the research bench with a safe working area between benches, with utilities provided on a grid. Depending on funding of research initiatives and the number of scientists, technicians, and equipment needed, the number of modules allocated to a particular group varies. This same modular approach can be applied to CTE spaces with a variety of utilities available to serve broad needs. This will require a larger initial investment of infrastructure. However, it will allow school districts to provide course offerings based on how their learners’ interests change over time and the inputs of their business partners without being limited by their architecture.

As designers, we ought to continually explore solutions which increase the flexibility—and therefore long-term relevance—of the buildings we design. If design approaches that empower our clients to modify their spaces and meet changing needs over the life of their building are implemented, then engaged learning will be supported.

A Path Towards Change

IBL and CTE are approaches that thrive with excellent pedagogy, culture, technology, partnerships, and thoughtfully designed environments. Implementing either approach is challenging, but it pays off in countless ways—including economically. The first step to implement and sustain these approaches is for educators, parents, and whole communities to demand change, which is rightly needed, as current educational infrastructures are stretched thin. Furthermore, educational organizations and strategic partners need to participate in an intentional, concerted change process to identify their goals—as well as the barriers to change—to outline the right path for transformation.

IBL and CTE are within reach for any community, but these programs require advocates. Are you ready to be that voice in your community?

Rebeca Carranza-Hicks is an educational planner that has contributed to public school projects in Texas for a decade. With degrees in architecture and design research, she marries her training with her passion to identify and champion user (human) needs in design.

Dr. Marilyn Denison is a Teaching and Learning Designer at DLR Group following a 25-year career in K-12 public education. With her educator lens, Dr. Denison bridges the connections with the school community and designers to identify and align the desired teaching and learning experiences within a compelling learning environment.

Taryn Kinney, AIA, LEED AP, K-12 Studio Leader, and Principal at DLR Group, is a native Texan who has successfully led the strategy, visioning, planning, and design of more than 4,000,000 square feet of learning space nationally and internationally. Kinney designs experiences for her clients that empower them to create and implement exceptional learning environments.