There is a lot to like about the Houston Botanic Garden (HBG) master plan proposed by the Dutch landscape and urban design firm West 8. It would boost Houston’s appeal as a tourist destination, increase surrounding property values, and repurpose a golf course in southeast Houston. So, why have residents in the surrounding Meadowbrook and Park Place communities mobilized in opposition to the HBG?

The designated site, the former Glenbrook Golf Course, is located just eight miles south of Downtown Houston, right off I-45. If the HBG can reach prerequisite fundraising goals by the end of 2017, a lease agreement with the City of Houston will give them the Glenbrook site for the next 30 years. The West 8 garden experience would begin as soon as one exits I-45 onto Park Place Boulevard — a four-lane commercial street that will be enhanced with trees planted on both sides.

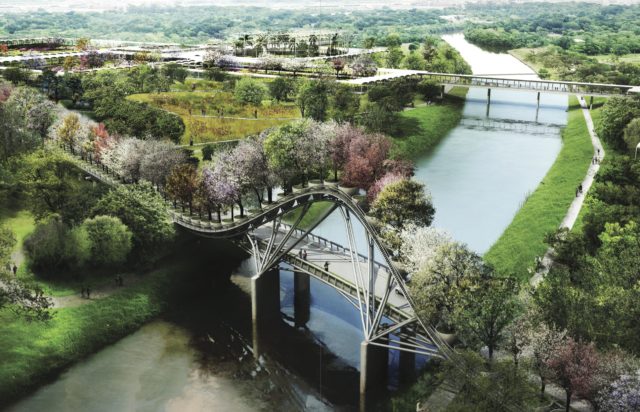

The Glenbrook site features two bayous. The original course of Sims Bayou, now called the Bayou Meander, snakes around the northern perimeter of the site on three sides. The more recent flood control expansion, Sims Bayou, bisects the site from southwest to northeast. Surrounded on three sides by the Bayou Meander and Sims Bayou to the south, the northern and largest portion of the 120-acre site has been appropriately designated The Island. With the garden entry from Park Place, the Bayou Meander acts as a threshold to the site. Beginning with the entry bridge that crosses over the Meander, West 8 uses the bayous to structure the placement of garden elements and choreograph the visitor’s movement through the site. The entry bridge leads the visitor along a scenic, tree-lined, mile-long procession along the western edge of the site – the Botanic Mile — towards the official arrival in the South Gardens on the other side of Sims Bayou.

West 8 is known for its highly original bridge designs and its HBG proposal does not disappoint. As the Botanic Mile approaches Sims Bayou, an arched steel bridge lifts a row of potted ornamental trees up high into the air. Assuming the floating trees can withstand hurricane-level winds, the HBG bridge, which is visible from I-45, could become the iconic Houston emblem. Not without its critics, the most prominent design element of the garden proposal has been called out in some online posts as "bizarre" and "contrived." On the other hand, the “tree-bridge” captures not only the cultivated nature of the botanic gardens, but also the idiosyncrasy of the country’s fourth-largest city that still has no zoning – think Orange Show, Art Car Parade and even more site-specific, the Dome House just south of the garden site.

After parking in the South Gardens, one can enjoy the entry pavilion and visitor’s center, browse the seasonal farmer’s market, picnic in the gardens’ expansive lawns, or perhaps take in a twilight movie or concert with the bayou in the background. The final reveal of the gardens is back on The Island. To get there, visitors will turn toward the direction they came from and take a covered bridge on the eastern edge of the site back across Sims Bayou. Renderings of The Island show children in a mesmerizing storybook-like world climbing staircases that wind around trees and exploring exotic plantings beneath a delicate water lily pad-inspired conservatory. On The Island, visitors can have lunch in a café surrounded by lush plantings, drop in on a presentation in the lecture hall, visit the educational facilities, or even attend a wedding or other special occasion in the event pavilion.

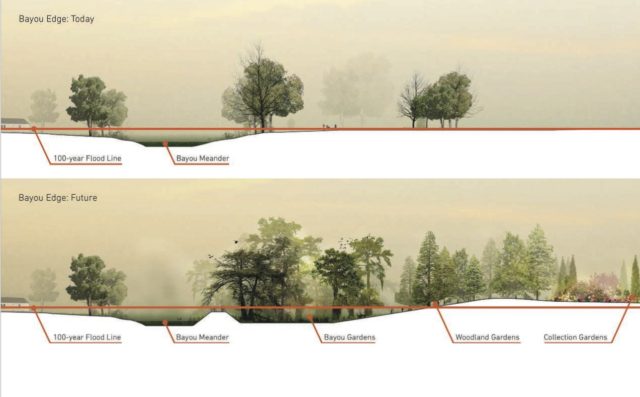

With extensive experience in flood control, West 8 also anticipates the natural flooding of Houston’s bayous. Sections cut through the site show the ground plane excavated along the bayou’s perimeter to allow overflow waters to collect and drain over time in the Bayou Gardens. Just beyond this overflow perimeter, the ground plane is lifted above the 100-year floodplain to protect the garden’s structures and plantings from the same floodwaters. This new site manipulation can easily be thought of as an extension of the already artificially-sculpted golf course hills. West 8 also accounts for Houston’s intense summer heat and sudden downpours with covered pathways that protect visitors from sun and rain as they walk from pavilion to pavilion.

With such an intelligent and thoughtful design proposal (however one feels about the tree-bridge), why are local residents opposing it? There are the usual concerns of disruption during construction and traffic congestion once the garden opens, but residents have also voiced more significant concerns that the gardens would mean a diminished quality of life for the community. Arguing that the botanic garden would deny the surrounding community access to significant greenspace that has become an integral part of their day-to-day lives, Houstonians for Urban Green Spaces (H-U-G-S) and Save Glenbrook Golf Course have combined forces in opposition to the proposed HBG.

According to Chelsea Sallans, who grew up near the site and organizes Houstonians for Urban Green Spaces, as the Glenbrook Golf Course usage and accompanying maintenance fees declined over the years, the site fell into benign neglect. Evelyn Merz, a key player in the Sims Bayou Coalition instrumental in rethinking of plans to line Sims Bayou with exposed concrete, says that as the golf course returned to its more natural state, a variety of wildlife adopted the course and adjacent bayou as home and, by happy accident, it became a nature preserve. Merz is concerned that construction of the HBG at Glenbrook would destroy what nature has reclaimed.

Animals were not the only ones adopting the golf course. So were locals, many of whom do not own cars and regularly cut through the site on daily bus commutes or walk to and from school or to the Park Place library on the northwest side of the course. Children learn to bike and neighbors take regular walks on the course’s paved walkways or jog along the bayou on the hike and bike trail.

Although the residents were charged a fee to play golf, a historic right-of-way gave them free passage along walkways that ran east and west through the golf greens and north and south across golf cart bridges that traversed the bayous.

Houston Botanic Garden would add one mile to walk between two public parks. Map from University of Houston Community Design Resource Center.

Houston Botanic Garden would add one mile to walk between two public parks. Map from University of Houston Community Design Resource Center.

Bayou Meander. Photo Paul Hester.

Bayou Meander. Photo Paul Hester.

Sims Bayou. Photo Paul Hester.

Sims Bayou. Photo Paul Hester.

From an urban design point of view, the site provides an important green link between the Meadow Brook and Park Place neighborhoods --- a green pedestrian link many would agree Houston needs more of. Charlton Park, with covered basketball courts, lies west of the site. Glenbrook Park, with a swimming pool and baseball fields, lies to the east of the course. Golf course walkways give residents easy access to amenities in both parks.

This local neighborhood linkage is not the only one that would be interrupted by a fenced-off Houston Botanic Gardens. Zooming out from the neighborhood to the larger city, Meadow Brook resident and University of Houston College of Architecture Professor Susan Rogers documented how the fenced-in garden would interrupt Houston’s natural “Emerald Necklace” of open green spaces linked by the bayous threading throughout the city.

As the Houston City Council, who voted unanimously for the HBG lease of Glenbrook, saw it, the exchange was a simple one --- a fee-for-use golf course for a fee-for-use botanic garden. Save Glenbrook Golf Course and H-U-G-S members argue that the exchange is a more complex one than reads on paper. While residents were never charged a fee for access to the golf greens unless they were playing golf, the botanic garden would fence community members out of the existing green space, forcing them to pay a fee to enter the gardens (albeit a discounted one for local residents) or walk the perimeter of the fenced HBG to get from one side of the golf course to another. They would no longer have access to walk or bike through the historic thoroughfare that linked Park Place and Glenbrook communities. In addition, 1.5 acres at the corner of Charlton Park would be taken and used for the HBG entrance.

It’s easy to understand why Glenbrook and Park Place residents are protective of their neighborhood --- it’s an unusually quiet and lushly verdant community that one does not often come across in Houston. Despite its less-than-pristine condition, on any given day scattered groups of golfers occupy the course. Golfers seemed accustomed to pedestrians on the walkway and despite golf balls flying over the links, the course is serene. Above gently undulating and winding sidewalks, Spanish Moss sways from the canopies of trees that puncture the greenways. The relative isolation of the site created by thick vegetation along the bayous makes the course feel as though it could be a world unto itself. Only the stacks from the nearby Texas Petrochemical Corporation that peek over the thicket and the constant roar of the freeway in the distance reminds the visitor that you are indeed still in the city.

On a Sunday morning in May, three men are fishing on Sims Bayou Flood Control course. One of them has already caught two catfish and a turtle. The fisherman has lived in Glenbrook all his life and not only fishes there, but frequently cuts across the course. Of the HBG, he said, “It will draw people for a few years and then it will die back down. If you ask me it’s basically a waste of money because the park is 'good as it is.'” He declined to be photographed or identified for this article, saying, “It’s not the people with three cents that matter, it’s the people with three million [dollars]." Walking back up toward golf clubhouse, father and son golfers load up their cart. For them, the transformation of the course is a non-issue. “We live out near Almeda Road. There’s about 10 courses within 15 minutes of us. They can do whatever they want with this one.”

Meadowbrook and Park Place residents opposing the garden also point out that if the 120-acre site is privatized by the HBG lease, Houston’s Sector 6, where Glenbrook is located, would lose 43 percent of its 240 acres of public green space in a community where a 2010 Health of Houston Survey indicates that the obesity rate is 40.3 percent as opposed to 30.5 percent citywide. The privatization of the site would drop the total acreage of parkland per 1,000 residents from 4.5 to 2.6 acres. Adding more credibility to this argument is a December 2015 Houston’s Park and Recreation Department Needs Assessment study (conducted before the city’s lease agreement with the HBG) that cited Sector 6 as needing additional green space per resident to bring it up to Houston’s median of 5.4 acres per resident.

Glenbrook was not the HBG’s first choice. According to local landscape architect Keiji Asakura, in the 30 years since he first proposed the gardens, several sites were vetted by the nonprofit. Inspired by a visit to Montreal’s Botanic Garden in the 1980s, Asakura envisioned a garden that would act largely as a research conservatory, emphasizing scientific discovery and community engagement. This engagement, Asakura thought, could include partnerships with the oil industry to investigate environmental remediation and with Houston’s healthcare institutions to research potential cancer-fighting botanic pharmaceuticals. Asakura brought this vision of a botanic garden to Nancy Thomas, then-president of the Houston chapter of the Garden Club of America. Thomas melded Asakura’s vision of a research conservatory with the primary mission of the Garden Club — promoting a love and appreciation of horticulture.

Thomas and Asakura, joined by Sadie Blackburn, Ann Hamilton, and Terry Hershey were able to secure $150,000 in funding. The group began meeting with then-head of the Parks and Recreation Board Oliver Spelman to explore potential sites including Hermann Brown, Memorial, Inwood, Howard and Hermann Parks. By 2002, the group had formed a non-profit and commissioned MTR Landscape Architects and Albuquerque architect Antoine Predock to design a master plan for the Hermann Brown Park site. With wetlands and trails, the Herman Brown site was considered a natural fit for a botanic garden, but the group’s hopes were derailed by plans for Highway 90 that would bisect the site – that and the fact that many deemed it too far out to attract volunteers. Asakura, who had envisioned a much smaller garden than the current proposal on the 120-acre Glenbrook site, also investigated using a portion of Hermann Park for the gardens. He found the Hermann Park site particularly appealing because of its potential to link the diverse communities of the Third Ward on the east side of Highway 288 with the Medical Center, Museum District, and Rice University. Mercer Park was also considered as a potential site, and according to Asakura, who left the nonprofit in 2005, is still a viable option. He suggests that the HBG could partner with the Mercer Arboretum and Botanic Garden to enlarge and enhance its existing acreage.

By 2015, the HBG had strong support from then-Mayor Annise Parker and the search for a site was narrowed down to two underutilized golf courses — the Gus Wortham Golf Course in the East End and the Glenbrook Golf Course in southeast Houston. Located inside Loop 610 with access to Houston METRORail, Gus Wortham was the HBG’s first choice. When residents near Gus Wortham in the East End balked at the placement of the HBG in their neighborhood and a nonprofit offered to restore the historic course, the Houston City Council voted unanimously to offer Glenbrook in its place.

From the city’s point of view, the HBG would add to Houston’s many other cultural and educational amenities and help boost Houston’s image as a destination city. The HBG would mean a one-time $90.3 million boost to Houston’s economy and an additional $19 million to $24 million in tourism in the years after the HBG opens. The gardens would also mean increased property values in Park Place and Meadowbrook --- and along with those increased property values, opposing residents say, gentrification, higher property taxes, rents, and the real possibility of some long-time residents being displaced.

While Ann Collum, president of the Glenbrook Valley Civic Club has come out in support of the HBG site, the Park Place Civic Club is formally opposed to it, reasoning that the garden would be economically exclusive and that modest-income residents will be priced out of it. Larry Bowles, president of the Park Place Civic Association was quoted in the Houston Chronicle as saying, “This just isn’t a good fit for our low economic area. Most of our people will be priced out of the garden once it is built.” Though the gardens would surely enhance the educational opportunities for students at nearby Park Place Elementary and Cesar Chavez High School, Merz fears that the HBG will become a botanic theme park largely for tourists and Houstonians who do not live in the area at the expense of the local community.

In many ways, Merz’s theme park assessment is an accurate one and not just because of the whimsical elements illustrated in the West 8 renderings. The proposed West 8 HGB scheme works on two levels. Taking advantage of the site’s proximity to I-45, the proposed scheme works as an iconic image at the scale of the city. The tree-bridge (or a more sustainable version of the proposed one) offers a spectacle as one approaches the city from Hobby Airport. And with careful orchestration of movement through lush gardens whether in a car or on foot, once you enter the confines of the site, the scheme works at the scale of the individual visitor’s experience.

Though West 8 does provide a 50-foot buffer between parking in the South Gardens and an adjacent residential area, the fenced-off scheme breaks down at the middle scale of the surrounding Meadowbrook and Park Place neighborhoods. Within the context of a mostly working-class Hispanic community among modest bungalows and ranch-style brick homes, the scheme feels alien. The lack of integration of the site’s role in the day-to-day life of the community is a symptom of a larger problem — a lack of an in-depth understanding and empathy with the rich inheritance of a site that includes not only its bayous, but also its surrounding inhabitants.

This middle scale is critical to Houston's emerging efforts at urban planning and design. The success of the Houston Parks Board's Bayou Greenways plan, funded in part by a 2012 bond that was approved by a large majority of voters, depends not only on the completion of linear trails but on their integration into sites along the way. If, as the current HBG master plan shows, the path is diverted off the bayou and a critical bridge requires a fee, the city itself would set a dangerous precedent for undermining the potential of Bayou Greenways to reconnect the city. "I fear that this garden will become a fenced compound designed to be accessed by car when it could be an integral part of the Bayou Greenways and the surrounding neighborhood," says Christof Spieler, A METRO board member, lecturer at Rice University, and Directer of Planning at Morris Architects.

The success of the new reimagined METRO bus system also depends on pedestrians to access high-frequency buses. When a low-frequency bus line on one side of the bayous was cut, residents could balance that loss with a higher-frequency line on the other side. So the loss of access to the pedestrian bridge has consequences not only for recreation but for the ability of Houstonians to go about their lives without a car.

The most apt example of a local institution whose campus not only enhances the city at large, but also its immediate surrounding community, is the Menil Collection. Ms. De Menil wanted to engage all of Houston in the enjoyment of art and that engagement began with the immediate community. Designed by international architect Renzo Piano, the main gallery at the Menil Campus is modestly scaled and even utilized the same building material of the surrounding bungalows. On any given afternoon, teenagers can be seen casually lounging or tossing Frisbees on the main gallery’s green lawns.

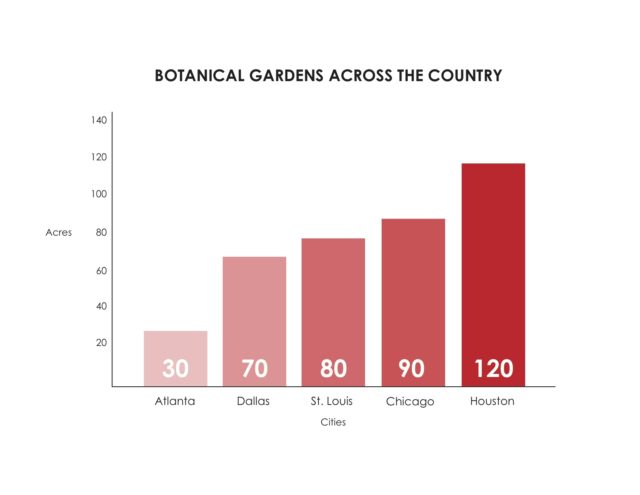

Really getting to know a place requires a slowing down of the process, and of course, this would mean adding more time and probably expense to a project that has been in the works for such a long time. But many residents living in Meadowbrook and Park Place feel that the whole process, from settling on the Glenbrook as the HBG site to the production of the master plan, has been rushed and their voices have not been heard. The West 8 images of the HBG are very exciting — seductive even — and will certainly contribute to fundraising efforts. But, is the current proposal really the highest and best long-term design solution both for the city of Houston and the surrounding Meadowbrook and Park Place neighborhoods? The community’s issues with the HBG plans are not unsolvable. Susan Rogers says, “[For me] it is not an all-or-nothing proposition. Just leaving a portion of the 120-acre site to the residents might be enough to reach a compromise solution that we can live with.” Rodgers’ students at the UH College of Architecture have shown how a smaller garden intervention in the range of 70-90 acres would allow the community adequate green space for a multiplicity of uses. To put this acreage in context with two successful botanic gardens — Denver’s botanic garden is 23 acres and Atlanta’s is a little more than 30 acres.

Jeff Ross, President and CEO of the HBG, told Cite that issues raised by residents of adjacent communities will be addressed in subsequent stages of the design process. "We are continuing to meet with community," he said, also noting that the master plan document notes concerns about access and that there is an ongoing effort to address those concerns. He has been quoted on multiple occasions as saying the West 8 master plan is a “road map” – not a finished product.

Continued dialogue with residents can open up possibilities for the garden design and make the HBG even more meaningful, not only to those who visit the gardens but to those who live in the community around it as well. In the words of Jane Jacobs, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”