When was the last time you went to an architecture exhibition? If it’s been a minute, you should see Steven Holl: Making Architecture at the Glassell School of Art. This week is your last chance: The free show closes on Sunday, February 14, 2021.

Installed in the ground floor gallery, the show collects drawings, models, photographs, and videos about recent projects by Steven Holl Architects (SHA). This is the show’s eighth stop; prior locations include New York, Seoul, Nanjing, Tokyo, and Seattle. Houston is also the third location where the show is being installed in a venue designed by SHA; the prior two were the Sifang Art Museum in Nanjing and the Bellevue Arts Museum in Bellevue, Washington.

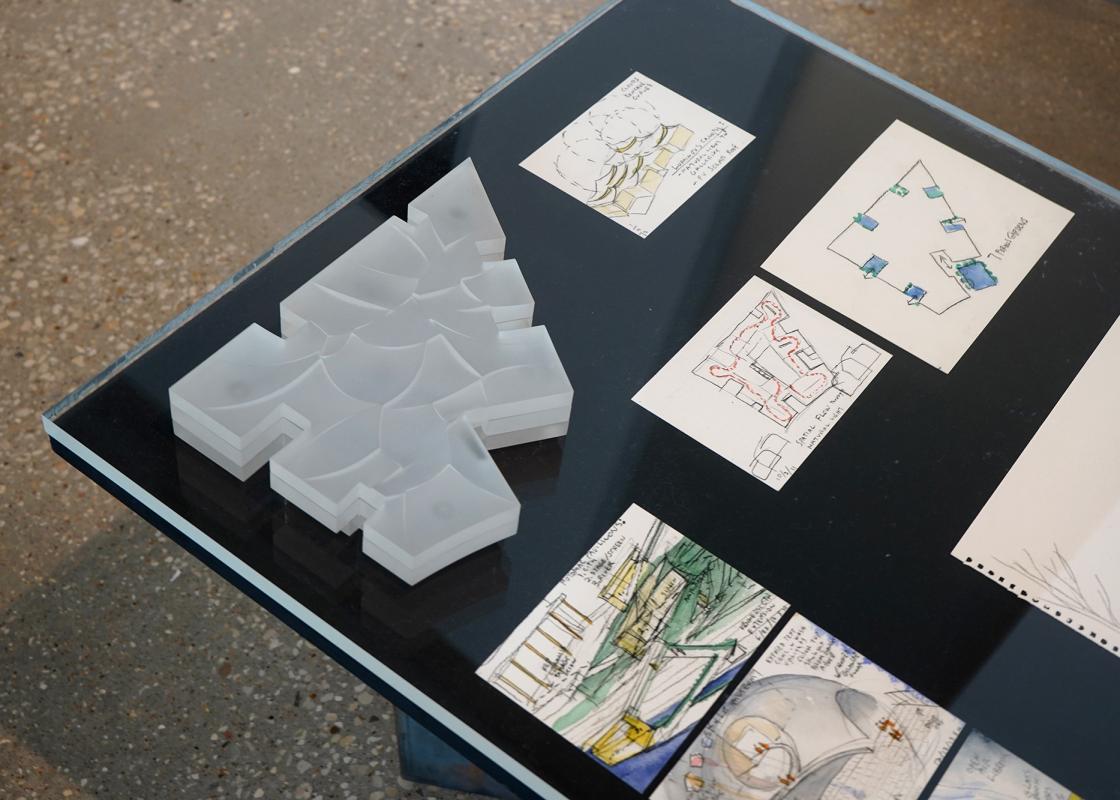

To start, Holl’s watercolors are arranged on low displays along with sketches on trace and select building elements like concept models, experimental models, and mockups of details like lights and door pulls. Six themes (“structuring thoughts”) organize these displays: interdisciplinary spaces and social condensers; abstraction, color, music; water, light, psychological space; subtractive additive; mind body; materiality, site, space, porosity. These ideas appear throughout SHA’s recent works; they link everything together.

It’s easy to look at the sketches and confuse one project with another, but that’s not a bad thing. This transference reinforces the continuity of SHA’s conceptual goals between and among singular projects. The movement of the body through space is a primary concern, a topic that links Holl’s work to architects like Le Corbusier and Álvaro Siza who respectively contoured and contour space to create experiences that are spatial and temporal at once—you can’t have one without the other.

The exhibition grows taller with a series of models on elevated bases. They start close to the floor and end up at and above eye level. You can wander among them and easily “project” yourself inside. While Holl’s watercolors are always presented with SHA’s projects, models are seen less frequently. They demonstrate the spatial qualities that the office is after. For me, they’re the most exciting part of the show. In some cases, it’s possible to see how an idea was fixed in a model and then “preserved” through construction to be seen in the finished building. Photos of this process of building, among other views that include Holl's studio in New York, are printed large and hung on the walls.

The entries in Making Architecture showcase SHA’s working methods but they compete with the space: The display area connects to the coffee shop, so it feels like you’re idling in a wide hallway to take everything in. A set of short films about Holl’s efforts loops on a small screen on the other side of the lobby—it’s easy to miss but a valuable part of the exhibition—and two examples of carpets designed by Holl appear on the walls.

The wall text rehearses a tired argument that pits working by hand against working on the computer: “The elimination of the human hand in the making of architecture alters how a building ultimately looks, behaves, and even feels to occupants. The hand–mind connection achieves subtleties and nuances of color, materiality, light, and space that the computer does not.” The handmade versus “the computer” is a false dichotomy about the operations of contemporary architects. The text goes on to situate SHA as a “practice that is directly opposed to this seemingly ubiquitous trend towards the digital. Holl’s approach to making architecture is based on the idea that he must continue to work by hand in order to achieve artful buildings.”

Contrary to this misleading claim, SHA’s ideas, while they may be first sketched on paper or explored intuitively through models, are made possible by a whole host of technologies operated by various entities at every step along the way when making buildings. SHA’s designs are buildable with high degrees of fidelity to their conceptual ambitions thanks to “the digital”—the larger project workflow utilizes coordinated softwares, steel manufacturing, glass production, lighting fabrication, and so on. It seems Holl’s powerful spatial visions have remained consistent over time and the construction industry has finally caught up. The models on display demonstrate this: The office regularly uses resin-impregnated plaster 3D prints, which results in a nice sandy, cast texture, and the big walnut model for Ex of In XII was milled with a CNC machine. SHA’s recent works, already formally complex, wouldn’t be possible without today’s available tech.

It’s not useful to resist “the digital”—instead, it should take its place among the right tools for the job. It's possible to design a terrible building by hand and a beautiful building on the computer; one medium isn't inherently better than the other. When the Glassell opened in 2018, Holl himself told me that the building was all about “‘using the technology of your time to get down to the simplest elements and put them together with the most advanced technology.’” Rather than the avoidance of technology, SHA’s practice is one that directs it to the highest of experiential ends. To ignore this achievement is to ignore all the labor between the first watercolor sketch and the final photo. Such an erasure would make invisible the intense years of effort by Holl’s colleagues and the broader constructive apparatus that makes buildings appear. Yes, Holl is a maestro, but even the best conductor produces silence without his orchestra.

The text suggests that “the potential for the future existence of architecture as an expressive art form” is somehow threatened by the quickening pace of production. This is a problem caused by neoliberal capitalism, not computer-aided design or building information modeling. It’s a crisis not of technology but of public imagination.

It’s also important to state that architecture is not art. Architecture is a separate thing that’s big enough to include ideas, writings, drawings, models, images, photographs, videos, exhibitions, and the movement of materials around the world to make buildings. SHA’s recent work is rich in spatial experiences, but at the same time it’s critical to question any narrative that alienates architectural processes from their creative and constructive environments. These realities don’t cheapen architecture—they make it richer.

Of course, the “thinking–making” couple of architecture can certainly be done artfully, as shown in this notable exhibition. To see for yourself, visit Steven Holl: Making Architecture before it closes on Sunday.

Jack Murphy is Editor of Cite.