Danny M. Samuels, FAIA, is Co-Director of Rice Architecture Construct (formerly Rice Building Workshop), Professor in Practice, Rice University, and Partner at Taft Architects.

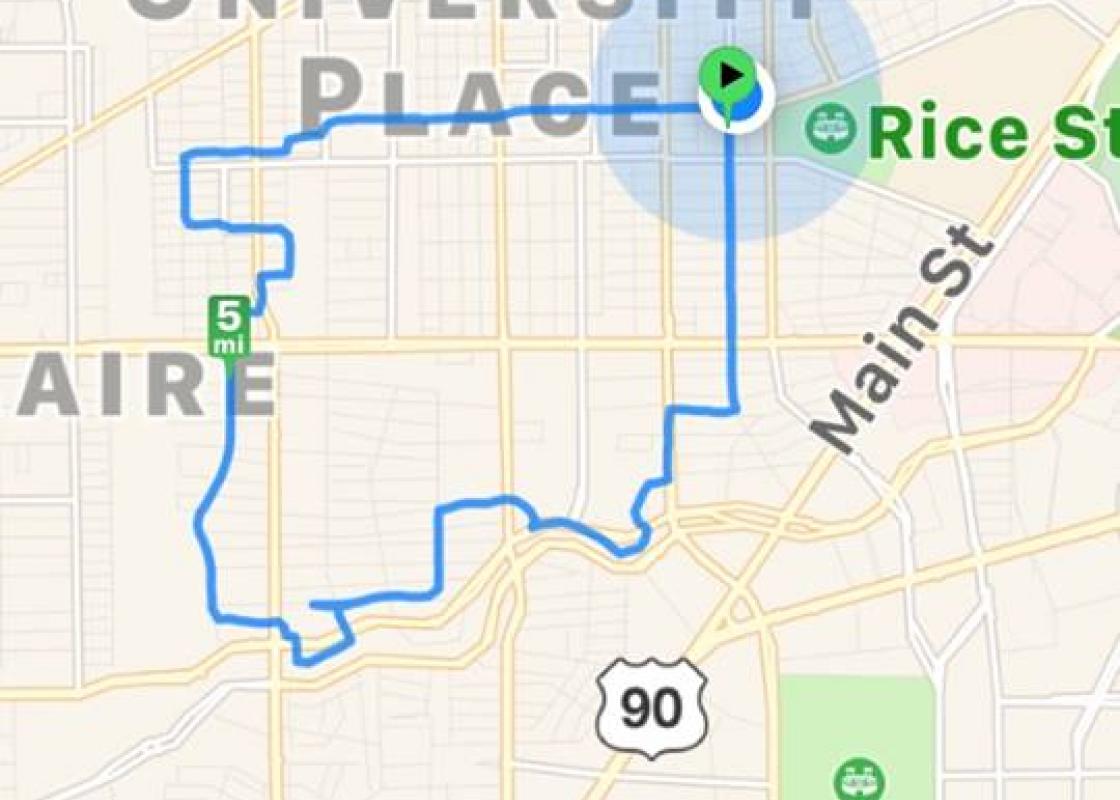

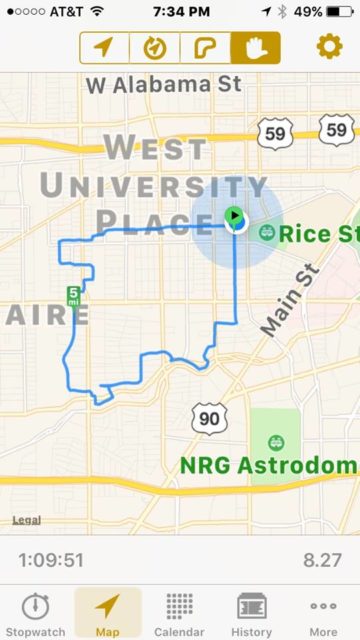

So far, in my Montrose neighborhood, and driving around Houston, I had seen only normal flood damage. So Saturday evening was quite pleasant, and seemed like a good moment for a bike ride, down to Brays Bayou. The bike path along the bank was pretty normal, except for some detritus in trees. The bayou was lying peacefully in its concrete channel, seeming maybe a bit like a bad dog for its recent debauchery.

Then I turned north into Aberdeen Way, and saw house after house with debris piled high in the front yards. This was the scene for street after street. Tired homeowners were piling and sifting, and talking quietly. I did not feel comfortable taking any pictures, but you have seen them on the news and after other floods. I am sure these scenes are playing out all around Houston.

These are upscale communities --- Southside Place, Braeswood Place, Bellaire --- that pretty much blend together. Bellaire and Southside have long-standing zoning codes, and more recently, stringent building codes, especially with respect to permeability, detention, and elevation.

But nonetheless, here was a massive flooding event. Zoning made no difference. But stricter building codes did.

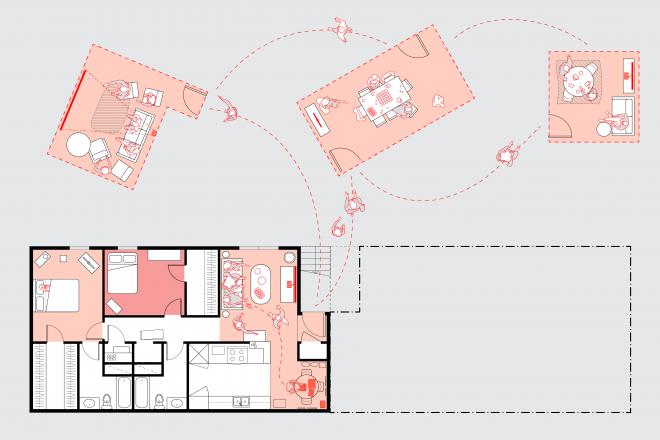

Two things struck me. One was that the damage was pervasive on every street for about four or five blocks parallel to the bayou. Then, next street, no damage. The change in elevation is not discernible, but obviously a little can make a big difference.

Second, where there were new houses, built to the newer, stricter building codes, and elevated from the street, the piles of debris were minuscule (mostly, I think, from the garage). This was particularly evident on Tartan Lane, two blocks north of the bayou, where a row of recently built houses was hardly scathed. It seemed like the size of the debris pile was inversely proportional to the floor elevation.

These houses were built under the City of Houston International Residential Code, which sets floor elevations based on floodplain maps. The lenders and insurance companies act as strict enforcers. (Of course, raising floors to an arbitrarily higher elevation on a specific site is no guarantee that it won't flood the next time.)

So, the current building codes seem to work. They are tortuous during design, permitting, and construction, and add a considerable cost premium. But the elevated houses (typically on pier and beam) definitely fared better than the low-slung original houses (on slabs).

Harvey was a rain event. We should not forget about wind. Here the code authorities, the construction industry, and the enforcers are even more in harmony. We should be good up to 110 mph, at least for new construction.

But the codes don’t apply to the existing houses, which are, rightfully, grandfathered. Until that housing stock is eventually replaced (or raised), these low-lying 1950s houses will continue to flood, or blow away.

The more prevalent these new construction standards become, the more the housing stock will skew to the fewer who can afford it. The Harvey flooding will likely accelerate that dynamic.

Read more by and about Danny Marc Samuels here.