This history of Houston and its water was printed in the Fall 1999 Cite (46) and reprinted in the 2003 book Ephemeral City. The author provides an update at the end of this digital version.

Paris has the Seine; Boston, the Charles; Memphis, the Mississippi; London, the Thames. Houston has Buffalo Bayou. Even the little San Antonio River makes us look bad. Chicago has Lake Michigan; Los Angeles has the Pacific; Miami has the Atlantic. Houston has the Lake on Post Oak.

Most great cities are easily identified with some body of water. The reasons aren't hard to understand. Until 19th-century industrialization brought railroads and 20th-century ingenuity perfected the automobile, watercourses were the fastest and safest means of transportation for people and cargo. Even more important than commercial reasons for planting a settlement on a waterway has been the practical human need for drinking and bathing water. But the most subtle and perhaps most powerful draw for situating oneself near some form of water is an emotional one. Poets and theologians have for all time pondered water as the central life-giving force.

So it was with good reason that Houston's founders greatly exaggerated its water features. In the famous Telegraph and Texas Register advertisement of August 30, 1836 (six months before there actually was a town), promoters audaciously claimed that Houston was situated at the "head of navigation" on Buffalo Bayou and went on to say that "Tidewater runs to this place and the lowest depth of water is about six feet ... . It is but a few hours sail down to the bay, where one may take an excursion of pleasure and enjoy the luxuries of fish, fowl, oysters, and sea bathing."

In fact, Harrisburg, at the confluence of Brays and Buffalo bayous just east of Houston, was the closest thing to the head of navigation, if indeed Buffalo Bayou could have been considered a serious navigable waterway. Today, the turning basin of the Ship Channel is near Harrisburg, not Downtown Houston. The Allen brothers initially tried to buy the site of Harrisburg, founded in 1822, but were unable to complete a land purchase there. Good promoters that they were, the founders never let on that the site at Buffalo and White Oak bayous was not their first choice.

Although tidewater does technically reach Houston, the water is brackish and in no way aids navigation. Nor was it a pleasant sail from Houston to the bay, given the tangled vegetation and dangerous stumps as well as obstructive overhanging trees draped with bug-infested Spanish moss and snakes. Furthermore, alligators ruled the swampy shores and freely swam wherever they pleased. Galveston Bay did and still does provide the luxuries of seafood and pleasant recreation, but it was not an easy destination from Houston in the city's early decades.

At the time of its Anglo settlement, Harris County had a substantial watershed from the San Jacinto River and 22 natural streams that included 44 miles of bayous, in addition to uncountable gullies. Once part of the ocean floor, this part of Texas is not sufficiently elevated above sea level to promote effective runoff, and dense clay soils exacerbate poor drainage. The elevation in Harris County rises from zero feet above sea level to barely 100 feet at the northern tip of the county. Rainfall in the Houston area, while not excessive (on average, there are 100 days per year with some rain, for a total of 48 inches) is problematic given the makeup of the vast watershed.1 So Houston began its history paradoxically touting water features that were, in fact, its main detraction. As this truth dawned on residents who experienced mud and flood almost annually, Houston developed a reputation as a place shaped by water. However, that water has shaped Houston in any profound way is far less intriguing than the way in which Houston has shaped its water.

Allen's Landing in 1910: Early in the century, Buffalo Bayou thrived with commerce all the way to Main Street. Photo courtesy Houston Public Library, Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

Allen's Landing in 1910: Early in the century, Buffalo Bayou thrived with commerce all the way to Main Street. Photo courtesy Houston Public Library, Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

*****

That Houston was founded on myth and greed is no secret. The great mystery is that it succeeded so wildly. One writer has bluntly stated, "Houston has never been so much a maker as a beneficiary of history, and disaster has often served it well."2 The first of those disasters was the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836 from which the Republic of Texas emerged with the war hero Sam Houston as its president. Harrisburg, the more established and better located spot for a capital, was destroyed in the fighting. So the Allen brothers, through political manipulation (the usual promises and personal favors), managed to make Houston the Texas capital. The lawmakers and their entourages swelled the infant town for only two years, leaving in 1839 for two reasons: politics and climate.3 Houston was an impossibly unpleasant and unhealthy swamp.

When Sam Houston was reelected president of the Republic of Texas in 1841, Houston bid to move the capital from Austin back to Houston. At issue were the archives of the Republic, which Houstonians believed were unsafe in Austin because of the threat of Indian attack. What became known as the Archives War ensued when the people of Austin bitterly opposed the removal of the archives, seen as symbolic of the whole government, to Houston. On December 30, 1842, a contingent of Houston "soldiers" mounted a secret foray into Austin in which they filled wagons with the archives and escaped under cover of darkness, only to be apprehended by Austinites on the way to Houston. Under armed guard the papers went back to Austin. It was lucky that happened, for in 1843 Houston endured its first major flood, which would have utterly destroyed the archives, as the entire town was submerged.4

Despite such problems, Houston devotees, with totally unreasonable optimism, had begun almost from the start planning to deepen and widen the channel of Buffalo Bayou, determined to make their city into a commercial emporium. Since Houston was poorly suited for agriculture (with the exception of rice plantations in northwest Harris County), the settlement attracted merchants and artisans instead of farmers and ranchers. In 1840, Houston received authorization from the Texas Congress to build and maintain wharves, and in 1841 the Port of Houston was established at the confluence of White Oak and Buffalo bayous. For a brief time the port charged wharfage fees and taxed boats using the channel, but it discontinued the practice when it became evident that captains would rather put off goods and passengers at Harrisburg (which had been rebuilt after its destruction during the Battle of San Jacinto) than pay for the privilege of docking in Houston. Sporadic dredging occurred, but only shallow-draft vessels could navigate Buffalo Bayou until after the Civil War.

An 1851 newspaper article summarized the town as a place with a "warm, wet climate, poor drainage and sluggish bayous."5 After the flood of 1843, drainage ditches were dug throughout the town, which helped somewhat, though ladies still tiptoed across streets and wore dresses permanently mud-stained at the hems. Raw sewage was dumped into the bayous from which Houstonians obtained most of their water. Cisterns and barrels in every yard collected rainwater for household use, but these were not always full. Though Houston held its own, managing to grow and thrive despite yellow fever and cholera epidemics, which were directly linked to wet climate and poor drainage, there was little evidence that the city could realize its vision for a grand future.

But then another disaster, the Civil War, worked to Houston's benefit. Just as the Battle of San Jacinto had destroyed the challenge of Harrisburg, the War Between the States gave Houston an advantage over its rival Galveston. Unlike Galveston, Houston was not occupied by federal troops, and Buffalo Bayou provided a fine waterway for blockade running. Houstonians, including William Marsh Rice, made fortunes supplying inland troops. Following the war, Houston, having been spared the devastation that occurred in much of the South, emerged with considerable capital brought to town by war profiteers. Such civic projects as dredging Buffalo Bayou could be comfortably financed. By 1870, it was clear that Houston's relationship with water was based not on recreation or quality of life issues, but on money.

In 1866 Houston municipal officials had established the Houston Direct Navigation Company with the hope of dredging Buffalo Bayou to a depth sufficient for ocean-going vessels. In 1870 the Buffalo Bayou Ship Channel Company began dredging, and the federal government declared Houston a port of entry, establishing a custom house. In 1872 Houston received its first federal grant of $10,000 to aid in completing the dredging project, one designed to create a 100-foot-wide channel nine feet deep. Work was slowed by a hurricane that hit Houston in September 1875 and caused $50,000 worth of damage. During this storm all but one bridge across Buffalo Bayou were swept away. Nevertheless, in April 1876 the first ship sailed through the new channel. The ironclad Clinton, a schooner-rigged side wheeler, came into Houston with 750 tons of freight and left with 250 cattle. Although it took a full ten years to realize the first "ship channel," the effort was but a baby step toward the dream of establishing a great port in Houston.

During Reconstruction after the Civil War, Houston fared well despite continued high water and poor drainage. In a second effort after construction of drainage ditches to improve these conditions, the city began to build large open channels to direct and control the flow of excess water. The two largest, along Caroline and Congress avenues, emptied directly into Buffalo Bayou. At the same time paved roads were built across the swampy plain into which Houston continued to expand. By the 1880s, ditches, channels, and both plank and gravel roads crisscrossed the town, creating a more or less effective drainage system. In 1878, James M. Loweree of New York was awarded a contract by the city to build the first waterworks to supply Houston with water from Buffalo Bayou. Loweree installed a dam above the Preston Street Bridge and laid pipes throughout the city. This water was not purified, and the water pressure proved too low for a consistent supply or for fighting fires.6 It was not until 1891 that a successful water works company supplied city water from 14 wells.7

During the last quarter of the 19th century Houston developed and prospered as a commercial rather than manufacturing community, in large measure due to the fledgling water channel and the establishment of important railroad connections. By 1890, the Deep Water Committee was busy planning further improvements to the ship channel. Houstonians had enjoyed the Gay Nineties with the rest of the country, and on New Year's Eve 1894 there was much to celebrate, including the fact that the U.S. Congress had approved the construction of a yet deeper channel.

Then came the Great Storm of 1900. This tragedy nearly caused Galveston's physical and economic demise, but it left Houston, Galveston's chief commercial competitor, in an advantageous position to take over Gulf Coast shipping. Plans were underway to widen and deepen Houston's ship channel yet again, and Houston already had a railroad network that enhanced its port position in a way that could not be duplicated on the island. Galveston's spirit had been crushed while Houston's continued, perhaps naively but indomitably. No historian analyzing the city of Houston should underestimate our brash can-do attitude, which for more than 150 years has shaped and reshaped its natural resources to great advantage.

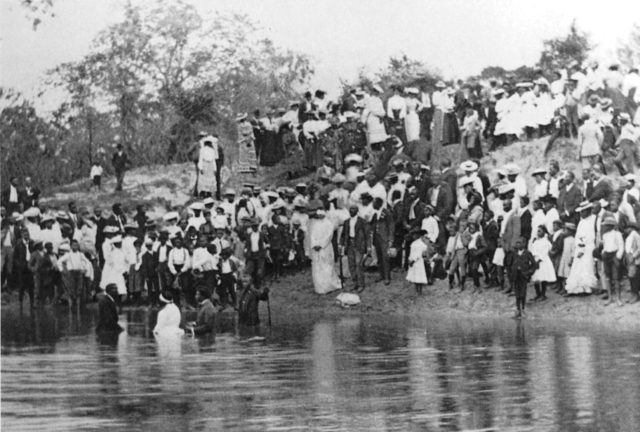

Houston's bayous have long been places to gather and, as seen in this circa-1904 photo, to be baptized. Photo: George Fuermann City of Houston Collection, University of Houston.

Houston's bayous have long been places to gather and, as seen in this circa-1904 photo, to be baptized. Photo: George Fuermann City of Houston Collection, University of Houston.

*****

With increasing sophistication and leisure time, well-to-do Houstonians concentrated on the pleasures of dining, dancing, and water sports. Boating and fishing, once necessities and chores, became diversions, and several male-only clubs were established: the Redfish Boating, Fishing, and Hunting Club (1865), the Andrax Rowing Club (1874), the O.O. Boat Club (1882), the Houston Yacht Club (1898), and the Aquatics Club (1900). The Houston Yachting Club (1903) met on a houseboat on Buffalo Bayou at the foot of Travis Street, and the Houston Yacht and Power Boat Club (1905) was organized to encourage scientific navigation.8

Those who did not belong to clubs or own fancy boats also had a recreational relationship with the bayous. For health and safety reasons, city ordinances had since the 1840s forbidden bathing and swimming in local streams. And even though daring youngsters had always defied the rules, swimming in the bayous, for obvious reasons, never became popular. And, curiously, neither did sport fishing. Until late 20th-century pollution decimated their ranks, fish abounded in the inland waters around Houston. But local fishermen preferred the smaller creeks and bayous, usually catching only enough to provide supper for their families. Until the 1910s even crawfish were plentiful in swampy areas away from Downtown. As for Buffalo Bayou, it was too full of commercial boat traffic to make a good fishing ground.

But the local bayous, including Buffalo, were not too overwhelmed with boats or fish to deter another group from using them. Christian sects that required baptism by immersion understood the sacredness of the local waters. For these baptisms an entire congregation would gather on the bayou banks to welcome new members, and often after the religious service most people remained for a picnic.9 Even so, Houstonians' recreational and religious relationship with local waters has been and still is limited. It was commercial promise that captured official recognition. With a pervasive "we can overcome anything" spirit, local citizens were determined to conquer the swamp and build a mighty river. That the inland city had withstood strong wind and high water in 1843, 1875, and 1900 while nearby cities were destroyed was a selling point that profoundly affected Houston's future.

Only in Houston has it been proven that oil and water mix. After the founding of the Texas Company in Beaumont in 1902, its director, J. S. Cullinan, began looking along the Texas coast for the best site for its headquarters and refineries. What he wanted was large acreage, fresh water, deep water shipping, and protection from storms and floods.10 He chose Houston, convinced that a sufficiently deep channel was under construction in Buffalo Bayou and that the threat from flood and hurricane was a thing of the past. This 1905 move to Houston of the oil giant that became Texaco is considered critical in the establishment of Houston as the oil and gas capital of the nation.11 In 1908, redredging of the Ship Channel was completed to a depth of 18 feet, with a turning basin just above Harrisburg.

Many writers have credited the oil industry with the development of the Ship Channel, but it well may be the other way round. Influential residents had decided long before Spindletop that a channel with a depth adequate for large ocean-going vessels was a must for Houston. As oil companies stacked themselves along the bayous, advances in marine technology produced vessels that required deeper drafts, making Houstonians once again question the sufficiency of their ship channel. They created a navigation district to control the watercourse and issued bonds to finance an even deeper channel. With the approval of Congress, the federal government matched local investment and construction began in June 1912. On November 10, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson pushed a button in Washington that fired a cannon at the new turning basin, opening the 25-foot-deep channel with great fanfare.12 This event ushered Houston into position to become a lucrative port and an economically stable city.

Before oil products became Houston's chief export, though, the wharves at the foot of Main Street and then from the port near Harrisburg were stacked high with bales of cotton. A local cotton carnival, the social event of the year, began in 1899. "According to an elaborately devised mythology, No-Tsu-Oh (Houston spelled backward) was the capital city of the Kingdom of Tekram (market) in the realm of Saxet (Texas). King Nottoc (cotton) emerged annually from the depths of the sea, or rather Buffalo Bayou, at the foot of Main Street to rule over his Court of Mirth."13 His arrival began a weeklong commercial exposition and non-stop carnival activities. In 1914, the name of the carnival was changed to the Deep Water Jubilee to celebrate the opening of the Ship Channel; however, the festival was discontinued the following year.

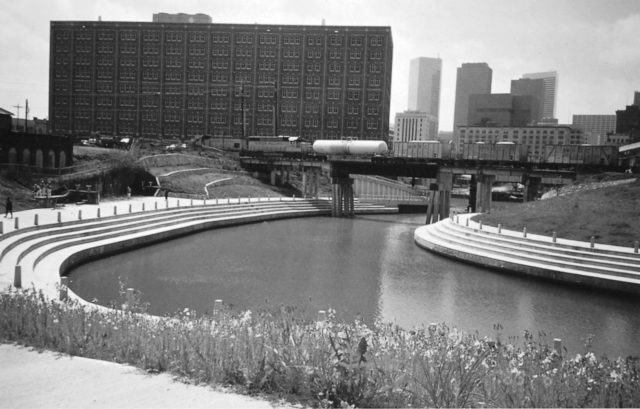

Championship Park on White Oak Bayou entering downtown demonstrates how some waterways have been tamed. Courtesy Harris County Flood Control District.

Championship Park on White Oak Bayou entering downtown demonstrates how some waterways have been tamed. Courtesy Harris County Flood Control District.

*****

In August 1915 a hurricane with 80-mile-an-hour winds struck Houston, killing three people. But the idea that Houston was not safe from high wind and water still did not sink, as it were, in. After Brays Bayou was hard hit by major flooding in 1919, the first serious flood-control measures were begun in Harris County. In 1921, a project to drain the 80,000-acre watershed of Brays Bayou started with the presumption that this would control flooding in Houston. It didn't. In 1929, after a 14-hour rainstorm, all of the bayous around Houston, including Brays, overflowed, and the San Jacinto River rose 30 feet above its normal channel. Although losses in Houston were close to $1.5 million, this sum did not touch the losses six years later from the most devastating storm in Houston's history.

In 1935, the buildings and streets of 25 blocks downtown flooded along with 100 residential blocks. Seven people were killed, and the Port of Houston was crippled for six months due to submerged docks and a ship channel clogged with tons of mud and wreckage. Uprooted tracks disrupted vital railroad connections. And nature finally got Houston's attention.

Politically, the timing of the hurricane was perfect. Federal works projects, particularly huge water infrastructure programs, were being created all over the country during the 1930s. In 1936, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stepped in to begin planning a limited flood-control program that would move high water away from Buffalo Bayou. To facilitate interaction with the Corps and process requests for federal grants, the Texas legislature on April 23, 1937, created the Harris County Flood Control District. Two years later, taxpayers in Harris County approved the first bond issue ($500,000) for an expanded drainage program. Meanwhile, federal and county programs were approved, adding over $35 million for the project. In February 1940, a comprehensive flood control plan was announced that called for the retention and diversion of floodwaters (Addicks and Barker dams) and two canals, one to extend from White Oak Bayou to the San Jacinto River, the other to run from a detention dam on Buffalo Bayou to Galveston Bay. These canals were "designed to protect the city and harbor from 'superfloods.'"14

The story of this massive plan was basically an attempt to move Harris County's excess water out into Galveston Bay with little regard for the natural environment. The arrogance of Houston planners once again raised its head with the notion that technology could fix anything. Not only did the storms and high water refuse to desist in the face of concrete channels and the like, they seemed to continue at a heightened pace. For example: heavy rains drowned 10,000 head of cattle and displaced 400 families (1940); Hurricane Audrey and another heavy thunderstorm caused flooding in Houston (1957); Hurricane Carla caused heavy flooding in southeast Harris County (1961); Texas Medical Center flooded and eight drownings occurred in three major thunderstorms (1976); a new U.S. 24-hour rainfall record of 45 inches was set in Alvin (1979); Hurricane Alicia and three major hurricanes caused severe flooding throughout the county (1983); and a major storm sent many bayous over their banks, flooding 1,500 houses and putting I-10 underwater (1992).15 It has been five years since significant flooding has occurred in Harris County, but officials warn that it is only a matter of time until the next big one comes.

What's going on? Claiming that all this recent flooding is new, environmentalists blame developers for paving over so much land in the county's watershed areas. Houston's rapid and often near-sighted development does retard natural runoff, but the gumbo soil that has been paved over was little help in absorption anyway. The hard, cold fact is that Houston has dangerous and destructive rainstorms, just as the Midwest has tornadoes and California has earthquakes. No one, not even rich Houston boosters, nor well-meaning engineers, nor tree-hugging naturalists can stop the water. Gary Green, operations manager of the Flood Control District, says that we have only three choices to deal with excessive water: move it, park it, or get out of its way. The move-it school had its day with channelization. And the park-it school continues to build dams and huge retention areas (such as the Barker and Addicks reservoirs). The get-out-of-the- way philosophy has established a federal buy-out program in Harris County that encourages those who live in the most flood-prone areas to sell out and move on. Rather than a program of flood control, which is impossible, Harris County now has a much more realistic program of flood management.

Even if the environmentalists are wrong in their assessment of the reasons for flooding, they appear to have won the day. Since Arthur Storey Jr. took over management of the Harris County Flood Control District in 1989, the way in which Houston deals with water has changed. Much of the work has become privatized, allowing resources and time to be spent on careful planning.16 Young planners and engineers responsible for current flood management programs seem much more sensitive to nature than their predecessors from the Corps of Engineers. For example, instead of channeling water in concrete culverts from natural wetlands, flood managers are planting marsh grasses that will filter standing water (which could be unhealthy) and stop erosion (which could lead to flooding). New detention basins are now designed to retain as much established vegetation as possible. Concrete channels are being removed in some areas, and new approaches tried. The idea of straightening out bayous and creeks to enhance drainage speed is no longer considered a good one.

Houston's developing ability to deal effectively with its own peculiar characteristics, including humidity, mud, and flooding, is a sign of its growing maturity as a city. Houston was founded on the myth that its location and natural resources were good things. It was also founded as a real estate venture, ironically one from which the Allen brothers never profited. Despite the fact that neither a beautiful lake nor a wide, high-banked river sits by its side, Houston has emerged at the end of this millennium as a green city because of the unrelenting arrogance of successive generations of leaders who have understood how to capitalize on external disaster and how to control the natural environment. They have effectively managed heat and humidity with air conditioning, and managed commerce through manipulation of the waterways. The masters are still in the process of gaining control of rains that cannot penetrate the non-porous soil or easily run off the flat land, but stay tuned.

2002 Update

From June 5 to June 9, 2001, Tropical Storm Allison pounded Houston with extremely heavy rain, producing the worst flooding Houston had seen in years. Sections of all highways and numerous secondary roads were closed; thousands of automobiles were abandoned; and at least 22 deaths were attributed to the storm. Some areas of greater Houston received more than 30 inches of rain, causing damages totaling several million dollars. The Medical Center was one of the hardest-hit areas: flooding of basement labs destroyed years of research data, and hospitals were closed for more than a week. Much of the city was without electricity.

This catastrophic occurrence should not have been a surprise. But, like storms of the past, it was met with awe and confusion. Houston, as always, recovered. But the scramble and the controversy continue as to how to improve drainage and prepare for the next flood.

Two articles published earlier in Cite also addressed the ongoing problem of Houston's water: Mary Ellen Whitworth, "Bayou Degradable: Up Against the Corps Again," Cite 28 (Spring 1992); and Barry Moore, "The Nature of Control: the Greening of the Flood Control District," Cite (Fall 1995/Winter 1996).

2016 Update

In twenty-first-century Houston, climate change has increased the intensity and frequency of rainstorms and subsequent flooding, adding a new dynamic to the existing problems of a low, flat, hurricane-prone location, poorly absorbent gumbo soil, unchecked development, and a continuing lack of effective planning and mitigation. Between 1941 and 1980 average yearly rainfall in Houston was 47.01 inches; in the last thirty years, between 1980 and 2010, this figure has increased almost three inches to a 30-year average (1981-2010) of 49.77 inches.17 In addition, there has been a significant increase since 1986 of the number of years in which Harris County has experienced more than eight inches of rainfall in one twenty-four-hour period.18

On September 13, 2008, Hurricane Ike made landfall over Galveston and, though its rating on the Saffir-Simpson scale for windspeed was relatively low, it caused extensive damage from flooding. A 22-foot storm surge swamped many coastal communities. In Cite 93, Jim Blackburn wrote about doomsday scenarios for the entire region and ways to avoid it. On May 15, 2015, rain totals of up to 11 inches brought about the "Memorial Day Floods." Houston again led the national news for several days after the April 18, 2016, "Tax Day Floods," when 8.92 inches of rain fell that day, hitting hardest the Cypress Creek area in north North Houston.

Inexplicably, Houstonians and melodramatic reporters once again seemed astonished. This latest episode, where rainfall was actually half of that experienced during Allison in 2001, has brought a spate of articles, reports, and editorials about what Houston must do. Everyone seems to agree that new and immediate solutions are essential. But what? The mayor considers appointing a “flood czar.” The new discipline of geospatial analysis can predict how new projects will affect the land and could be an effective planning tool for assessing runoff and flooding from major storms, but so what? When will developers stop ignoring the weak permitting rules concerning mitigation when wetlands are covered with concrete? Every generation comes up with brilliant new solutions (channelization, dams, diversion canals, reservoirs). A new, but underfunded, city initiative called ReBuild Houston aims to restructure and maintain the city’s drainage and street system.19 But all the czars and planning reports will be useless until unzoned Houston figures out how to successfully regulate development, fund infrastructure improvements, strengthen building codes (particularly for houses), and convince Houstonians to be prepared for the next flood that will happen.

↩ 1. Gary M. Green, P.E. Director of Operations. Harris County Flood Control District, interview with author, November 15, 1999.

↩ 2. Jerry Herring, Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Houston (Houston: Herring Press, 1992), p. 14.

↩ 3. Margaret Swett Henson, "A Brief History of Harris County," in Houghton,el al. Houston's Forgotten Heritage (Houston: Rice University Press, 1991), p. 6.

↩ 4. Houston, A History and Guide, compiled by workers of the Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in Texas (Houston: Amon Jones Press, 1942), pp. 56-60.

↩ 5. David McComb, Houston: A History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), p. 6O.

↩ 6. Ibid., pp. 87-88.

↩ 7. Houston, A History and Guide, p. 92.

↩ 8. Ibid, p. 341.

↩ 9. Dorothy Knox Houghton, "Domestic Life," in Houston's Forgotten Heritage, p. 259.

↩ 10. McComb, p. 80.

↩ 11. Marta Galicki. "The Architecture of Oil." Cite 39, Fall 1997, p. 47.

↩ 12. Henson, p 10.

↩ 13. Houghton, p. 312.

↩ 14. Houston, A History and Guide, p. 124.

↩ 15. "Riding the Waves at Change: 60 Years of Service," (Houston: Harris County Flood Control District, 1998), pp. 7-15.

↩ 16. Green interview.

↩ 17. Statistics compiled by author from information on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (website http://www.srh.noaa.gov/hgx/?n=climate_iah_normals_summary#2000), accessed April 24, 2016.

↩ 18. Kim McGuire and Mike Tolson, “Is this the new normal? After storms turn Space City into Flood City experts believe the future could be even worse,” Houston Chronicle, April 24, 2016, 4A.

↩ 19. ReBuild Housotn website (https://www.rebuildhouston.org/index.php/about-rebuild-houston/facts-history/faqs), accessed April 24, 2016.