Follow OffCite's State of Museums series and the forthcoming issue of Cite. Use the hashtag #StateOfMuseums to view related content on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

An art exhibition on Gandhi could go wrong in so many different ways — too political, not beautiful, overly biographical. When the Menil Collection announced plans for a major program inspired by his life, I worried.

What set Gandhi apart from other twentieth-century revolutionaries was not only his adherence to nonviolent means but his embrace of a total political, cultural, and material alternative to industrialization. He wrote more about food and clothes than about governance. He obsessed over the proper way to bathe, when to sleep, whether to drink cow's milk.

Some years ago, when I taught Gandhi's writings to a class of college freshmen, some of the students didn't realize that he'd led a national revolution. They thought of him as a food-obsessed crank.

But it's the weird interconnectedness of his experiments that keeps Gandhi so relevant today. His focus on the details of daily life, what we put in and on our bodies, gives him staying power. He wasn't trying to replace a British colonial government with an oligarchy of Indian elites. The marches and boycotts were almost sideshows. His utopia was all about people's basic relationship with stuff, and each other.

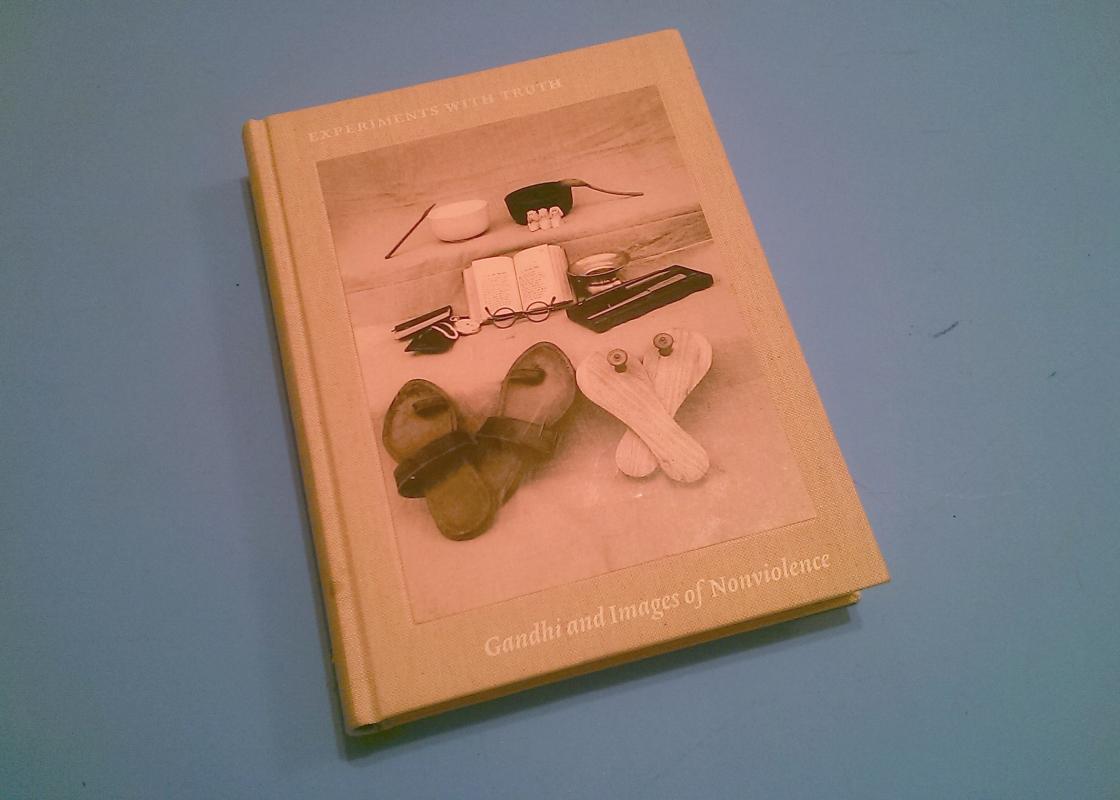

"Gandhi persistently refuses to sink into the oblivion of history," writes Josef Helfenstein, director of the Menil, in his foreword to the exhibition's accompanying book, Experiments with Truth.

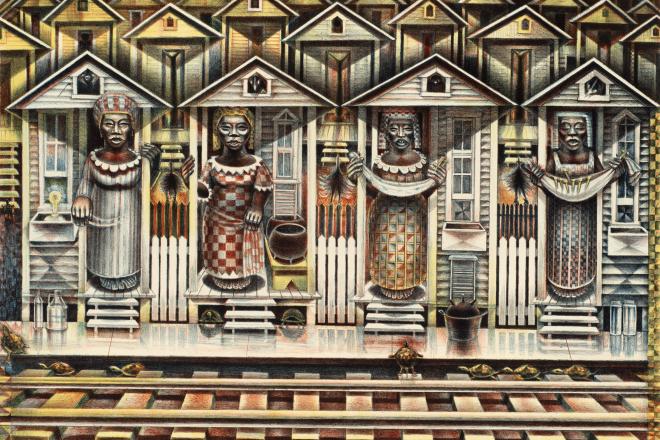

The Menil exhibition is a hodgepodge. It draws together modern art, folk art, spiritual works from antiquity, and contemporary works from the Menil Collection and other institutions. The odd assortment can be confounding. There's an oxen yoke, undated quilts from Gujarat by unknown women, a series of photographs by Henri Cartier-Bresson of Gandhi's last days, a wax head of Abraham Lincoln. (Lincoln? Didn't he preside over a war?)

Some pieces more than hold their own. The seventh- or eighth-century Buddha with its head lopped off is both disturbing and hopeful, as is Hose for Fire and Other Tragic Encounters, crafted into a weirdly beautiful abstraction by Theaster Gates. Kim Sooja's video installation, A Needle Woman, is not to be missed; it is an antidote to the endless fear shoved down our throats by 24-hour news coverage.

But what won me over at the Menil exhibit was a wall displaying over 270 varieties of rice, a little handful of each type on black trays arranged in long rows. The differences in the seeds are astonishing: tan, black, red, flat, broad, round, thin, coarse, shiny. As an Asian Indian, I thought I had a handle on the diversity of rice. How mistaken I was! The names of the rices are a wonder. To try to pronounce them is its own kind of spiritual and artistic exercise — Harisankar, Mahipal, Magai, Nalipathara Mukta, Bayaguntha, Punni.

The rice display is part of Amar Kanwar's Sovereign Forest installation, which chronicles the struggle of people in Odisha, India, to keep steel mills and other multi-national industries from taking over their lands. The rice is displayed along with a film, handmade books, and newspaper clippings that together are beautiful and truly Gandhian. Our entire way of life is called into question. When I eat bulk basmati rice, a standardized international commodity, am I not complicit in a system that destroys regional knowledge, supporting violence on communities that developed so much biodiversity over thousands of years?

Kanwar's gorgeously produced film shows the contested lands in Odisha — sea, marsh, farms, rivers — that look eerily similar to the Houston region (sans, of course, the massive industrial complexes that already dominate here). I imagine a Houston version of Sovereign Forest. And I wonder why we don't have our own Amar Kanwar.

The Menil did not stop with mounting a remarkable exhibition and publishing the book, which I highly recommend. Numerous events were held at the Menil and other institutions all around town, including Project Row Houses. I attended a forum called Black Lives Matter: Getting Beyond the Hashtag at the Rothko Chapel that helped attendees find strength in one another by sharing experiences and historical perspective. I spoke with some of the Houston Justice Coalition activists who have devoted tremendous time and energy to addressing criminal justice reform.

Although the exhibit did not make any permanent changes to the building, I see the Menil Collection in a new light. As the 2011 book Art and Activism: Projects of John and Dominique de Menil beautifully documented, the Menils combined their interests in art and architecture with education, alternative media, and civil rights campaigns. That combination is not always evident to visitors and the Menil risks losing touch with that legacy by simply presenting art works from the collection.

In his OffCite.org review of the Art and Activism book, John Pluecker writes, “It’s been the central dilemma of the Menil Collection (and modern projects generally): how to institutionalize a spirit and an energy of experimentation?” The Gandhi project — exhibition, book, and events — gives a fulsome answer.

Experiments with Truth: Gandhi and Images of Nonviolence is on view at the Menil Collection until February 1, 2015.

by Raj Mankad