This article is the first of a two-part series by artist Carrie Schneider coinciding with the reopening of Emancipation Park.

“In the beginning, there was function … form came later,” says Jesse Lott of Emancipation Park.

I am interested in how this new form was imagined; and, now that it is built, what it means for the surrounding communities as new developments are displacing long-time residents of the Third Ward; and, finally, how artists respond in their work and in collaboration with the Emancipation Economic Development Council. First, some history.

The “beginning” Lott refers to, in 1872, is a field at the corner of Elgin Street and East Broadway, purchased by African Americans who were formerly enslaved and who pooled their money to secure a piece of land in Third Ward where they could safely celebrate Juneteeth.

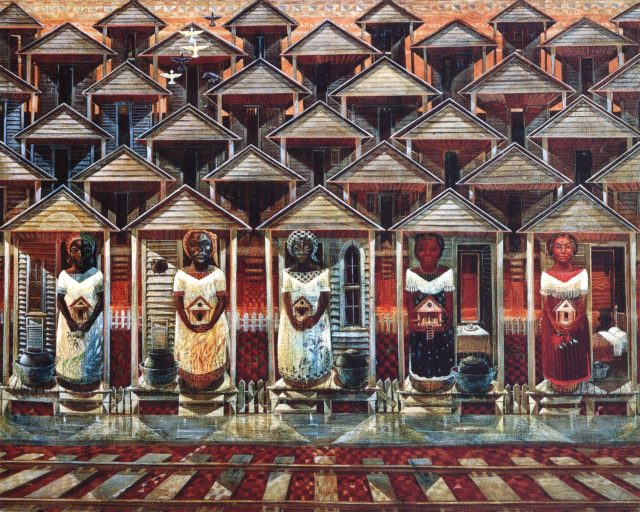

Jesse Lott is an artist, an elder, a mentor, and sage to many of Houston’s makers. He, along with seven original founders of Project Row Houses: James Bettison, Bert Long, Rick Lowe, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples, and George Smith, were inspired by how the work of John Biggers avowed an architecture transported from a West African homeland to a post-slavery occupation of space on the Texas Gulf Coast. In 1993, they in turn transformed a block of shotgun houses into a space for artists to create installations.

Since then, the work of Project Row Houses has helped make a row of shotgun houses into the poster child for contemporary art. It has helped anchor an enduring model of community based arts among the more recent popularity of “social practice” or “socially engaged art” — the defining art “ism” of our time. As it has grown steadily over the years, the Project Row Houses campus now abuts Emancipation Park’s southern edge, and this proximity puts pressure on the role of artists as the trajectory of Project Row Houses and the thirty-three-million-dollar renovation of Emancipation Park converge.

How do these stories: a park in Third Ward, an internationally celebrated Houston arts institution, and the role of artists in our time, intertwine? From my perspective, it is a story of how our imagination of space impacts the real use of that space; claims that space for public, civic, and social expression; and influences which bodies performing what acts occupy that space.

As the younger colleague of a handful of artists whose practices developed alongside Project Row Houses, a fraction of whose work I will touch on here, and as a 2017 Project Row Houses and University of Houston College of the Arts Fellow, I will ask, in light of the renovation of Emancipation Park, what responsibility artists have to the spaces we are currently choreographed into "activating," and to reimagining the nature of that choreography itself.

Jesse Lott’s strand of wisdom that “before there was form there was function,” continues with the assertion that the people can get it back if they can take back the function. I will go on to detail how the Emancipation Economic Development Council is endeavoring to reclaim this function for the residents of Northern Third Ward, but first, to unpack Lott’s perspective, let’s look at some the uses of the park through its history.

And now there is the built form of these images.

What can be perceived, in these sun-algorithm kissed renderings of the renovated Emancipation Park, of the imagined future uses intended to occur there? In contrast to those in the historic photographs, the figures in these renderings don’t hold up signs, or fists, or dance, or take up space so much as stroll or stand. They don’t occupy space to remake it, they move through it.

As Emancipation Park opens and the Juneteenth 2017 celebrations take place, many residents in a neighborhood of 78 percent renters are wondering what such an importation of thick amenities may mean for them? In particular, why isn't the first and major investment in redevelopment, which would be welcome in Third Ward, in a host of other forms (well funded public schools, affordable housing, healthy food, health and senior services)? Why is it taking the form of this park renovation? And who is it for? After all, the park was being put to use before the renovation. In fact, Emancipation Park wasn’t just a privately guaranteed place for African Americans to celebrate Juneteenth, it was the first public park in Houston.

Let’s hold that thought and the quality of these images in mind and pivot to artists.

I cannot speak for the black community or the residents of Third Ward, but I can speak on how artists are used in space in our time, and it is necessary to get a feel for this given choreography in order to appreciate what artists have been doing very differently in proximity to Emancipation Park.

In Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class (2002), in the new dominant arts funding model of “Creative Placemaking,” in city tourism policy, in arts district designation protocol, in cultural plan consultancy practices, in museum campus expansions, in city rebranding efforts, the given choreography for artists in our time is emphatically evident — we’ve been given a script, handed stage directions: Just add artists and the economy will flourish! Just add “creatives” - your city is world class now!

Jack Yates and others gather for Juneteenth on ten acres of land purchased in 1872 with pooled money. Courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

Jack Yates and others gather for Juneteenth on ten acres of land purchased in 1872 with pooled money. Courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

Martha Yates Jones and Pinkie V. Yates in a decorated carriage in front of the William E. Jones house, on their way before or to Deroloc (Colored backwards), the African American alternative to Notsuoh (Houston backwards), the Houston Cotton Festival, 1900s. Courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

Martha Yates Jones and Pinkie V. Yates in a decorated carriage in front of the William E. Jones house, on their way before or to Deroloc (Colored backwards), the African American alternative to Notsuoh (Houston backwards), the Houston Cotton Festival, 1900s. Courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

These ideologies are illustrated in renderings for arts and culture multiuse spaces, in vinyl ads on fences that hide construction and advertise the lifestyles of the soon-to-be residents of high rise lofts, in real estate fly-through videos for “urban” condominiums, in Cultural Planning consultancy splash pages, in City of Houston rebranding ad campaigns, which feature a fever pitch of artist bodies performing: Space activation / Amenity Provision / Tourist attraction / Workforce retention / City boosting / Decorating / Invigorating / Ameliorating / Entertaining

But…what if this choreography does not look interesting to us?

What happens when artists go off script?

There are exceptionally powerful examples from right in Third Ward. Adjacent to, next door from, across the street from – and even in the name of that street itself - Emancipation Boulevard.

For example, beginning in 2012 artist, Philip Pyle II distributed signs around the neighborhood that a Whole Foods was coming, and stickers around the neighborhood for the then nonexistent Emancipation Park Civic Club.

Pyle II’s work has company among a network of artists whose work has intertwined with that of Project Row Houses as their practices have developed. As W. Wright and C. Herman write about in "No 'Blank Canvas': Public Art and Gentrification in Houston’s Third Ward," “their public performances critically engage the spatial processes of gentrification and ghettoization in their neighborhood.”

Autumn Knight for example, lived in the first Row House Community Development Corporation (CDC) apartments in 2005, in the CDC apartments on Anita after returning from grad school, and then stayed nearby until 2013. Knight is now receiving international attention, including residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and a re-presentation at the Krannert Art Museum of performances from FUTZ, a research practice she piloted in her rowhouse throughout Round 37.

In 2015, with Robert Pruitt as MF Problem, Knight hosted a public art event created in response to a published list of America’s 25 Worst Neighborhoods which featured Sauer at McGowen. It was a Sunday Social, drawing on “rural/Southern/African American traditional picnics, socials, and jubilees that include dancing, live music, food, and socializing” that aimed to essentially flip the spatial imaginary of this given piece of land from “most dangerous intersection” to “nice place for a picnic.” Sunday Social was preceded by the ongoing event known as the Mobile Block Party hosted at the gas station at Francis and Dowling throughout 2011.

It is important to note that these works don’t just pull moves from conventional maneuvers in the playbook of gentrification, like inserting an artist’s work into the window front of a property awaiting flipping, although they may use such moves in order to flip them inside out. They may use such signals of property value enhancement (as in Pyle II's fake Whole Foods ads) to open a glitch in the expectation of space or reveal an aspect of that space (food desert), but then within that glitch they articulate a new possibility (Nu Waters co-op). They may use such moves (make a soon-to-be razed or vacant property into an "installation space") to instead bring into the fore a recovered history (grandma's house in the Beauty Box, community picnics in Sunday Social). The work is not the making-more dollars on the sale price of a piece of space, but the making-possible of the fellowship of a social public on a given space. The work is always centered on the answer to “who is it for?” being “us” and “the people who are here” and “those who have made this space so far.” It is also important to note that this is not merely a detournement of the artist-instrumentalizing property-value enhancing Creative Placemaking choreography, but a continuation of a much deeper, much more politically assertive movement belonging to many more than those designated “artists.” In fact, it is quite clearly similar to the gesture of the founders of Emancipation Park. They, freed from being property, purchased property on which to be free, importantly not just for their own social gathering, but for the securing of the possibility of public gathering on city space, as the foundation for the fellowship of a social public throughout generations.

Naima J. Keith, Lauren Woods, Autumn Knight, David Herman, and RonAmber Delaney in Knight’s “The La-A Consortium,” November 12, 2016. Photo by Kim Leeson, courtesy New Cities, Future Ruins.

Naima J. Keith, Lauren Woods, Autumn Knight, David Herman, and RonAmber Delaney in Knight’s “The La-A Consortium,” November 12, 2016. Photo by Kim Leeson, courtesy New Cities, Future Ruins.

Consider another of Knight’s works, The La-A Consortium, recently debuted at the New Cities Future Ruins conference at Southern Methodist University, in which Knight had five fellow conference workers improvise as administrators of cultural organizations convening for an administrative meeting. They read through the consortium’s member foundations, including: Teiondreia Contemporary Art Think Tank, Quensenia Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Daquan Collection, Diminishaa’ Institute for Contemporary Criticism, Chaniquah Cultural Research Network, and so forth, and then improvised a mission statement. The meeting’s procedures were substantiated by movements of the body; side eye, shoulder shake, and rubbing the colleague’s kitchen, or hair at the nape of the neck most resistant to any kind of product, straightener, or assimilation. It is a powerful work for not just imagining a new work within the given world, but imagining a world in which new kinds of work are fostered. New kinds of work are fostered because their given support structures are otherwise. Their support structures are otherwise because of who populates the decision-making, programming-determining tables. This particular move - turning a thing inside out AND remaking the structure on which it stands - appears frequently in the work around Project Row Houses, like an ambient muscle memory, or a common habit of mind.

Like Jesse Lott whose retrospective at Art League Houston held space for the work of his mentees because his practice practices its own form of radical pedagogy. Or Otabenga Jones & Associates who mined the Menil Collection and respatialized the People’s Party’s community initiatives through a mural on the Main Street wall of Lawndale Art Center: Don’t just make a new made thing- make a new way of making.

Otabenga Jones & Associates, “The People’s Plate” mural, which utilizes imagery by graphic artist and Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas. Retrieved from blog.creative-capital.org.

Otabenga Jones & Associates, “The People’s Plate” mural, which utilizes imagery by graphic artist and Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas. Retrieved from blog.creative-capital.org.

We hear this in Rick Lowe’s oft told version of the Project Row Houses origin story in which a high school kid from the neighborhood visits Rick’s studio in the early 90s and asks why, as an artist, was he just painting the problem instead of designing solutions?

This young person’s question was not just answered once, made-up summarily by the stroke of genius of a visionary founder. Rather, its resonating potential is made-real in the continual answering – reasking – reanswering of this question over and over in the institution’s twenty-two year lifespan. It is made-real in the abiding acts of care in the day-to-day remaking work of the many people who make up Project Row Houses: stitched together in ongoing conversations between resident interests and artistic concerns mediated by the staff, attended to by the women that lead and participate in the Young Mothers Program, taken up by the Row House CDC which builds and rents out affordable housing. In the lending of space, as with the bike shop which became Workshop Houston or with Cookie Love's Wash N Fold and its connected artist studios. In the giving of attention to young persons, as with a range of education programs under Sister Hamdiya and the Summer Studios program. This arc of responsiveness to the needs of the neighborhood is now unofficially joined by another endeavor, launched in part by and administratively hubbed at — but not at all claimed by Project Row Houses — the Emancipation Economic Development Council, which aims to ensure that the “if” in Lott’s “the people take back its function” is put to rest.

Carrie Marie Schneider is an artist based in Houston. You can find her other contributions to Cite here This article is the first of a two-part series.