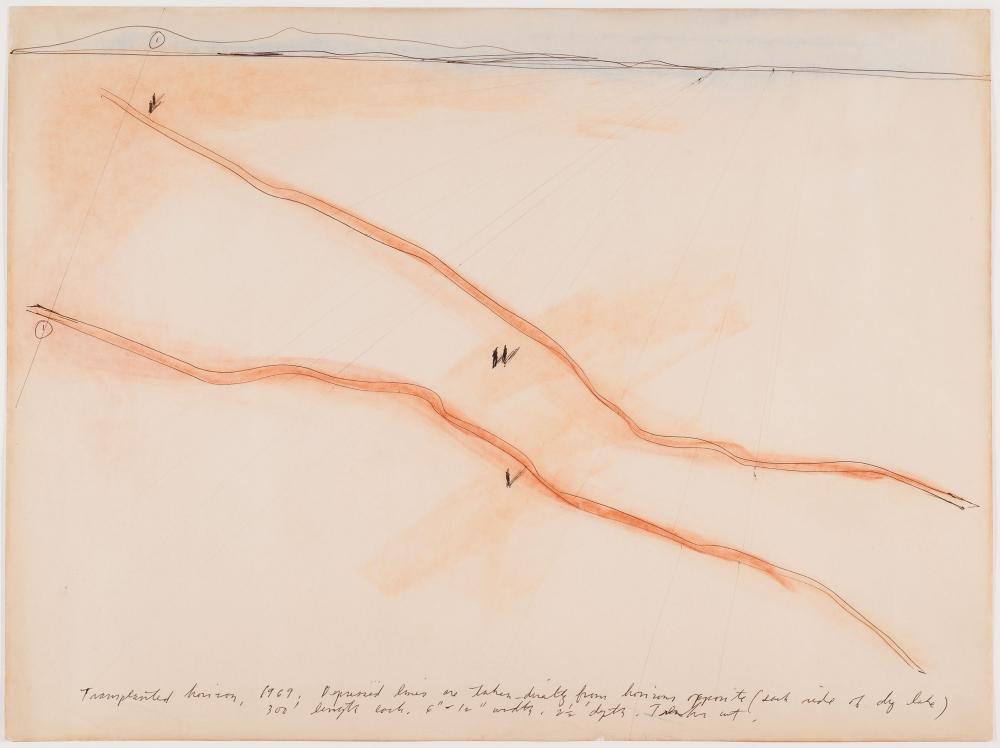

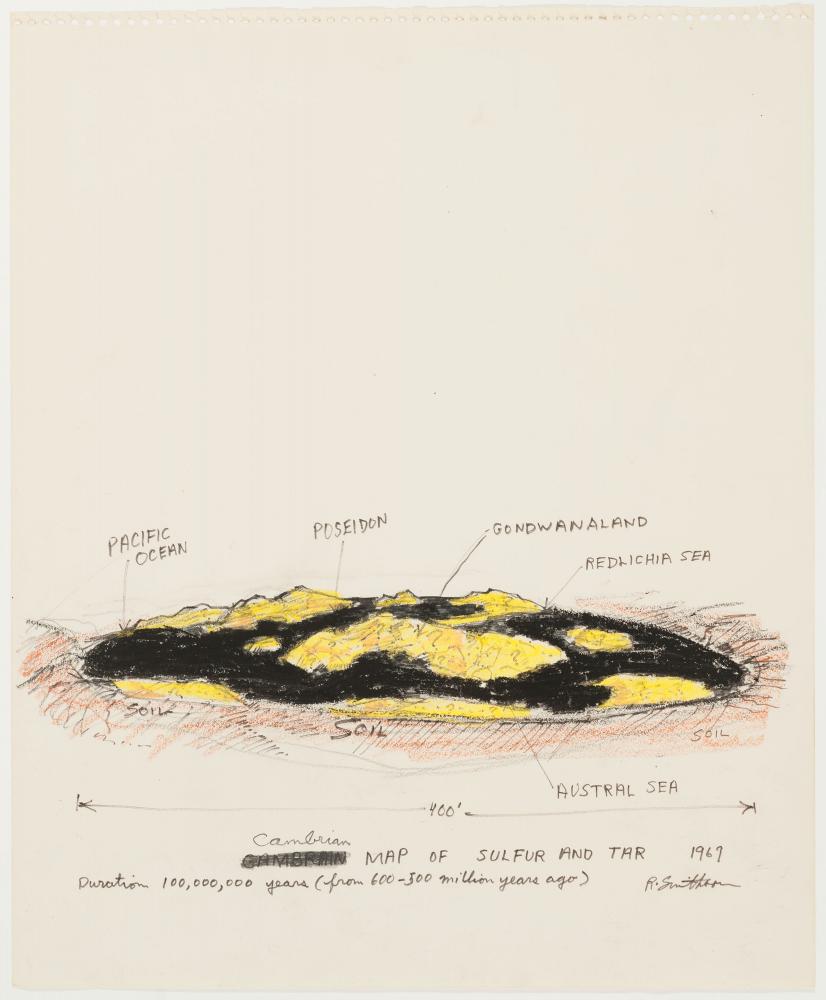

There’s something humbling about Dream Monuments: Drawing in the 1960s and 1970s, currently on view at the Menil Drawing Institute until September 19, 2021. It’s a kind of ghost show, as some of its offerings call to us from a more starry-eyed era in U.S. history and culture. In 1969, just as Apollo 11 was readying for takeoff, John and Dominique de Menil began work on a deliriously ambitious exhibition. It would be organized under the rubric of the “monument,” which they defined broadly enough to include projects of narrative and visionary architecture, as well as the then-nascent Land Art movement. This meant actual installations in Houston by artists like Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson—or, such was their intention. As the de Menils approached the fundraising and installation phase, the show collapsed under its own conceptual weight. Lifted from the grave of the archive, it now returns as an expanded collection of sketches, rough drafts, and scribblings, haunted by transformed attitudes toward the genre of the monument and monumentality itself.

The Menil Drawing Institute itself is a lively contribution to the Menil Collection’s campus. An inviting porch offers shade and seating to the public, and there is a marked, pleasing contrast between the angles of the exterior façade and the distinct homeliness, almost coziness, of the interior. I’ve seen a couple of exhibitions there, including the fantastic and challenging The Condition of Being Here: Drawings by Jasper Johns, and find it to be a comfortable and un-self-conscious place to inhabit, compared to the grandiosity of many other exhibition spaces. Part of this may simply be that the low lighting produces a less sterile, clinical experience, the downside of which is that viewers may occasionally find themselves squinting at details.

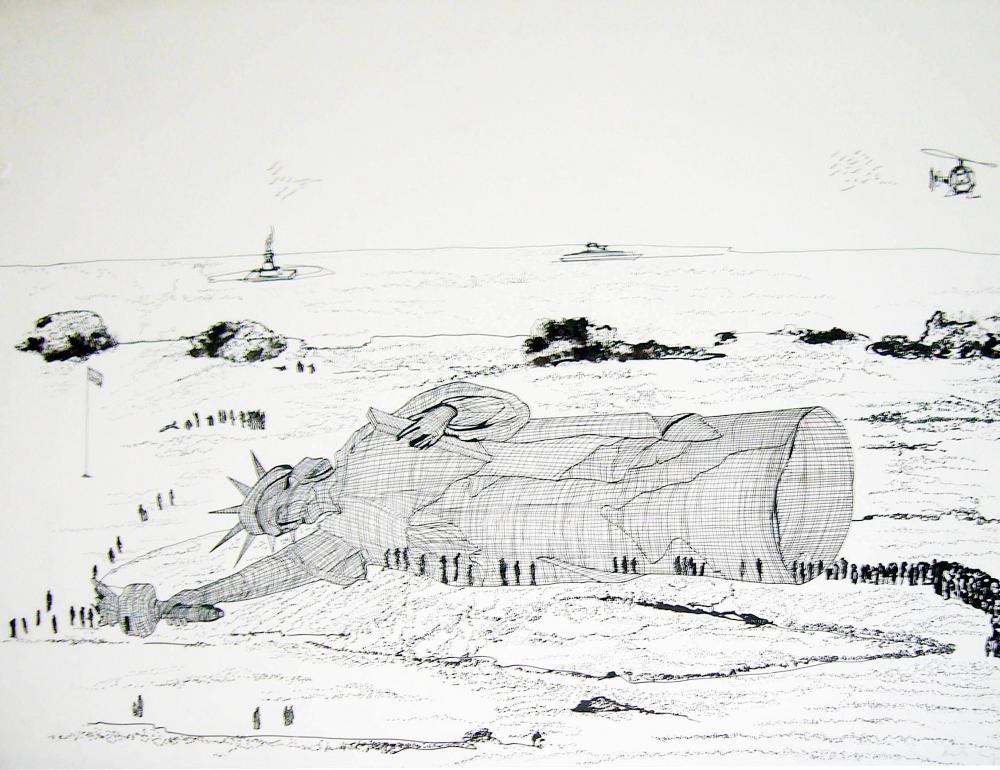

It’s a warm and forgiving atmosphere for this exhibition whose original efforts “failed,” in a sense, as nothing was realized other than the ideas themselves. Some of these proposals, it’s true, also don’t work in a more ideological sense: the watercolor renderings of would-be earthworks by Heizer in particular, while pretty, show a certain masculinist and primitivist iteration of the Land Art movement which has aged poorly. More likable are the absurdist proposals for colossal bowling balls and spoons from Claes Oldenburg. Dream Monuments also offers the monument-as-critique, with salvos of gloomy irony from Walter de Maria and Robert Morris, or the potent, melancholy Estatua de la Libertad acostada II (con publico que la recorre), by Marta Minujín.

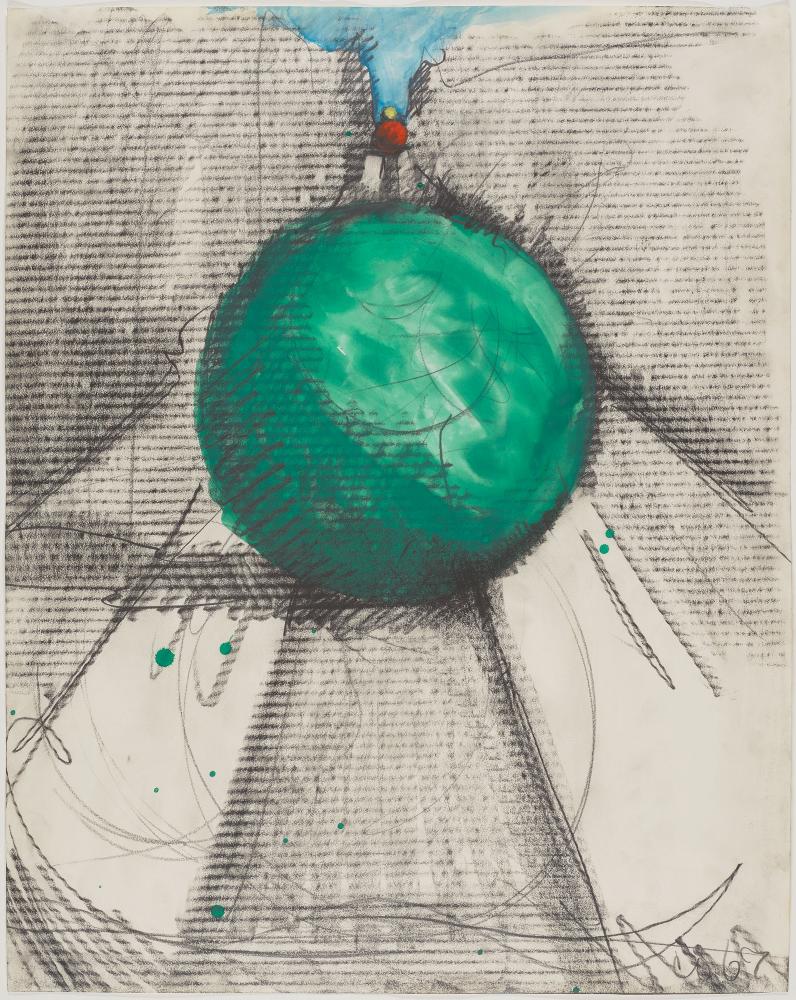

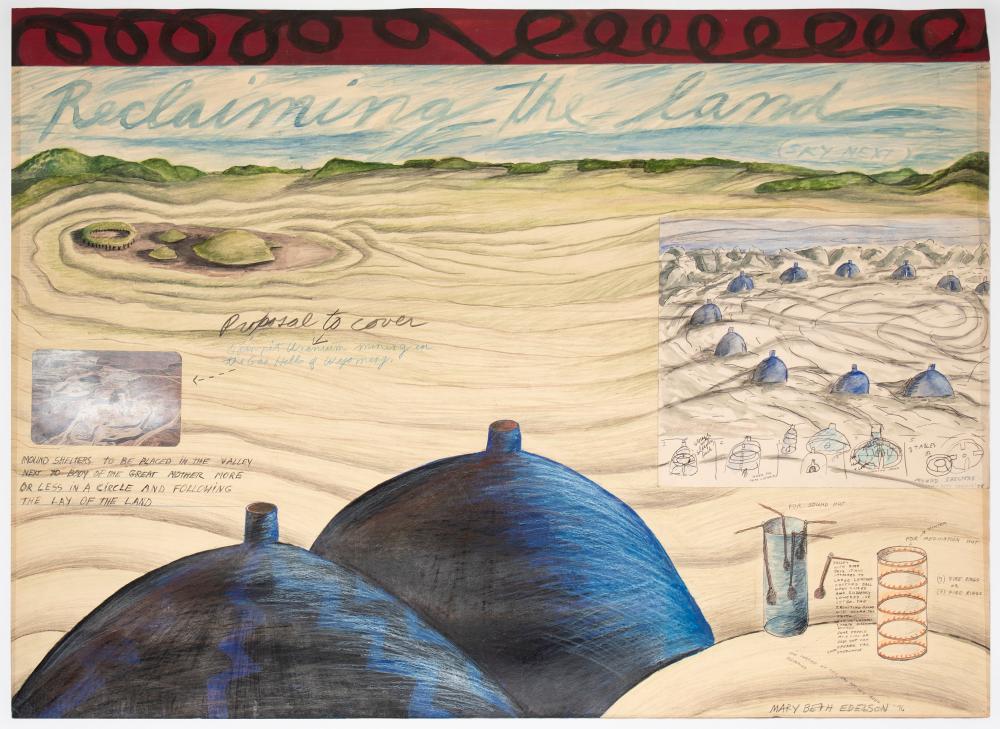

While the archival portion of the show may be of interest to Houstonians, including two in-depth essays on the Menil’s website by Kelly Montana and Erica DiBenedetto, the curators have wisely chosen to expand the artists included beyond the white male lineup initially envisioned by the de Menils. Multimedia work by Beverly Buchanan is included; a page of her City Walls Sketchbook filled with luminous dark abstraction shows her likely influence on the Black Compositional Thought of Torkwase Dyson. Numerous colorful fantasies from Mary Beth Edelson feature prominently. While the bioessentialist features of her feminist visions limit them somewhat, their immediacy and spirit of play bring them into constellation with other “insider-outsiders” like Niki de Saint Phalle (a show of her early work just opened at the Menil Collection), Cecilia Vicuña, or even whimsical architect-turned-ecoprophet Paul Laffoley.

If Dream Monuments is haunted by the dreams of its former intentions, dominant among these is that of the Land Art movement, accompanied by its discontents. A typewritten proposal by Morris, which would have involved growing the “currently most profitable crop” on a plot of land with the help of a financial backer, with proceeds to be split between the artist and the backer, was among those never realized, and thankfully so. Like works by Smithson and Christo, who proposed a massive mastaba of stacked oil barrels, this kind of “Land-Art-as-critique” signifies the ironic tragedy of the eco-ironic artwork, which, in making its critique, exacerbates the very problem it identifies.

In the decades since Dream Monuments, the movement of Ecovention, which describes artistic interventions that call attention to environmental degradation, has emerged both within and alongside but also against Land Art; it’s represented here by Mel Chin, an artist from Houston with whom I was unfamiliar, and Agnes Denes, whose reputation continues to swell.

The Chin work, a schematic for SEE/SAW: Operational Drawing—a sculpture which involved a hydraulically powered platform of grass that lowers when stood upon, raising another platform nearby—was one of the only works in the show that did come to fruition, in Menil park. If the “ecovention” of Chin’s work isn’t entirely clear, its kinetics propose a literal shift of perspective, which ecological theorists generally agree is called for.

The Denes drawing, set in an angled vitrine, is a minimalist study fitting into her decades-long theory and practice of ecological rehabilitation, one of the fullest and most thoughtful realizations of the art-historical concept of Ecovention. One wishes, though, that the organizers had contextualized the study within Denes’s larger project, which would have made the politics of its intervention more dramatic.

As DiBenedetto observes in her essay “Monumental Dreams: A Story for Houston, ca.1969”: “indeed, from today’s perspective, Dream Monuments failed not in the fact that it never happened but in that it risked a teleological view of the monument that ended with a circumscribed group of artists.” Teleology is certainly one aspect of the monument—and monumentality—that has been called into question in the half-century since the show’s first stirrings. With its thoughtful, spectral reactivation of the de Menils’ initial concept, this new Dream Monuments offers opportunities for departure from tired teleologies through contemplation of both their failures as well as the points at which others have deviated. This is especially poignant in our era of contested monuments to racist and colonial violence. Wall Column, a concrete work by Buchanan, seems to particularly anticipate where we find ourselves now: dusty orange prisms at the feet of gallerygoers suggest, somehow at the same time, both auction blocks as well as empty pedestals, their icons gone missing—or, perhaps, toppled.

Sam Stoeltje is a PhD candidate in the Department of English Literature at Rice University. They have written for Hypocrite Reader, La Voz de Esperanza, and Speculative Arts Research, and they blog at www.paracultures.com. They sing, they dance, they are from San Antonio, and they believe in ghosts.