Terrence Doody is a professor emeritus of English at Rice University, author of Confession and Community in the Novel and Among Other Things: A Description of the Novel. He has received NEH and Mellon grants as well as several prestigious teaching awards at Rice.

In 2008 as the Menil Collection was surveying its holdings in African art, the curator Kristina Van Dyke wrote: “The couple did not have a predetermined agenda and did not aim to be encyclopedic in this or any part of their collection.” They were free, therefore, to leave their African pieces deliberately idiosyncratic, and without a deliberate plan, they were able to exercise their imagination and courage across a very wide range of cultures, periods, and styles. In doing so they were also able to express their belief in art’s spiritual dimension, and to do this on a grand scale with the freedom the Schlumberger fortune allowed them.

The “spiritual” is a theme that runs throughout William Middleton’s long book, Double Vision: The Unerring Eye pf Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018). Spiritual does not simply indicate the traditional religious meaning of the sacred or religious objects—crosses, for instance, or ceremonial African masks—which were part of their collection, nor is it quite the equivalent of the traditional proposition that art is “useless” and, therefore, the object of pleasure and contemplation. Ceremonial masks are spiritual and, in their culture, useful. The objects that the de Menils valued personally, and always had around them in their homes, suggest something else. An African totem and a surrealistic painting are not representational in the traditional Western sense, nor realistic. So, what is it that they “present”? “The real” that they each embody? And what is the effect when they are juxtaposed and put into play with each other?

Middleton does not answer the question himself. His best example of the issue comes from a show at the Museum of Fine Arts. Shortly after James Johnson Sweeney came to the MFAH, he organized Three Spaniards: Picasso, Miro, Chillida in 1962. Sweeney was a famous curator who had worked at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In Cullinan Hall, the Mies van der Rohe addition that opened in 1958, was a ten-thousand-square-foot gallery, and in it, writes Middleton, "Sweeney placed only five works of art. Centered on the expansive rear wall was Picasso’s Nude Under a Pine Tree (1959), a painting of abstracted, flesh-colored forms, part cubist, part classical, over six and a half feet tall and nine feet wide. In the room, toward the right side, placed on an immense rectangular white plinth, was a monumental sculpture by Eduardo Chillida, Abesti ogora (1960). The piece, which weighed three thousand pounds, was made of rough, dark oak. It was over five feet tall, five feet deep, and eleven feet wide. On the left half of the gallery, Sweeney placed a 1961 tryptich by Miro, Blue I, Blue II, and Blue III. Each of the abstract paintings, in intense blues, reds, and black, was over six feet tall and nine feet wide. The Miro canvases, suspended from above, appeared to be floating in the middle of the space. 'I don’t think there has been an exhibition to match it since,' said Edward Mayo, MFAH registrar."

When we look at a painting on a museum wall, our relation to it is fixed in a fairly determined space. The spaces between these five works, in the field of inter-relationships they created, is closer to what I imagine is the spiritual realm the de Menils sought. Physical first, but then ineffable. Fourteen years later, Dominique opened, writes Middleton, "a smaller exhibition with one of her most theatrical installations. Secret Affinities: Words and Images by Rene Magritte . . . . Affixed to walls were enigmatic quotations by the artist that had been painted on signs in the form of large puffy clouds. 'Mystery is not just one of the possibilities of the real,” he announced. “It is absolutely necessary that the real be mysterious if there is to be any real at all.'"

Double Vision falls into four principal parts: John and Dominique’s family backgrounds and early marriage; their experience during World War II; their move to Houston, which was their real entrance into the art world and their life and effect on the city; and then Dominique’s life after John’s death in 1973. Dominique Schlumberger belonged to a distinguished Protestant family that included Francois Guizot, an important intellectual, born at the time of the French Revolution. His many accomplishments included a thirteen-volume translation of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. He was also one of Alexis de Tocqueville’s instructors at the Sorbonne, a member of the Academie Francaise, and a founder and editor of La Revue Francaise. Her uncle Jean was a friend of André Gide and, with him, founded La Nouvelle Revue Francaise. Her father Conrad was a physics professor who taught at the Ecole des Mines de Paris and was awarded the Croix de Guerre and Legion of Honor for his service in World War I. He later became a pacifist. His own curiosity turned him toward developing an electrical means of locating minerals beneath the surface, at a time in the early twentieth century when oil was about to change everything.

Jean’s great-grandfather Paul-Alexis-Joseph Menu served under Napolean and became the first Baron de Menil. Jean’s grandfather was an engineer who built bridges designed by Eiffel and helped develop the French railroad system. His nickname in the family was “Big Daddy Railroad,” and Dominique was certain “Jean was much like him, . . . a great worker with tremendous physical resistance, a builder, and an organizer.” But when Jean was born in 1904, the family was suffering a financial crisis, which only sharpened his ambition and drive, as he became the fourth Baron Jean Menu de Menil. (In 1949, he became simply John de Menil.) But by the time he met and married Dominique, he had begun to collect, on business trips throughout the world, whatever artifacts caught his eye—African masks, a bark rug, Polynesian wrap skirts.

John’s family was deeply Catholic, Dominique’s Protestant, and this was an impediment to their marriage for which they had to work out a compromise. Then early on, they met a number of important Catholic theologians, including Jacques Maritain, as well as the Surrealist painter Max Ernst, who had a profound effect on them. At virtually the same time that Dominique converted, a new term, “ecumenism,” entered the Church’s vocabulary and theirs and came eventually to describe not only their taste in art but the religious sense behind all the social and political work that they did throughout their lives. They also met a young designer, Pierre Barbe, who renovated their Paris apartment. Middleton says Barbe’s elegant modernism started a straight line to the style of their townhouse in New York (designed by Dominique and Howard Barnstone), to their Philip Johnson house in River Oaks, to the Menil Collection designed by Renzo Piano.

It wasn’t until 1938 that John could be talked into joining the firm of Dominique’s family. Then, early in World War II, he served in the French version of the CIA, the Deuxieme Bureau. His assignments included sabotaging shipments of oil, for which he won the Croix de Guerre. But the Deuxieme Bureaux dissolved in 1940 and he began his career at Schlumberger, which took him away from home for long periods of time as he supervised the company’s foreign offices in Eastern Europe, Venezuela, and the United States. In 1940, Dominique and the children went to live in the South of France as the Nazi occupation began. There, Dominique had their third child, their first boy, and immediately began the arrangements necessary to get to New York. There they were reunited with Father Marie-Alain Couturier, a Dominican priest and the editor of the journal L’Art Sacre, who had been their most important mentor. In their next stage, John and Dominique moved to South America, where they were separated from the children for extended periods. In April of 1945, Dominique delivered their second boy in Houston. By then, they were wealthy and ready to stay in Texas. By this time, too, some of the children had developed resentment at these separations, and their mother developed a deep guilt; later in life, she thought this separation may have been a sin on her part. They began buying Surrealist paintings, inviting their friends to visit them in this lonely foreign city, and building the life they became famous for. Father Couturier had said they had a moral obligation to buy good paintings, and Middleton thinks that without this order from on high, they would not have “amassed such a meaningful collection.”

This is only the halfway point in the book, and the very detailed narrative that follows sometimes feels like “and then, and then, and then,” on several planes at once. They were extraordinarily energetic and seemed eventually to know everybody—many of whom they invited to have a meal at their house and even to stay there. John died of cancer in 1973, and the children wondered if their mother would have the desire and energy to carry on at the same speed. She did. And before she died in 1997, at the age of 89, what she had accomplished, with John and after his death, is an appropriately visible record of their lives.

Demoinique de Menil and Karl Kilian at teh University of St. Thomas Art Department library. Photo courtesy Menil Archives, the Menil Collection.

Demoinique de Menil and Karl Kilian at teh University of St. Thomas Art Department library. Photo courtesy Menil Archives, the Menil Collection.

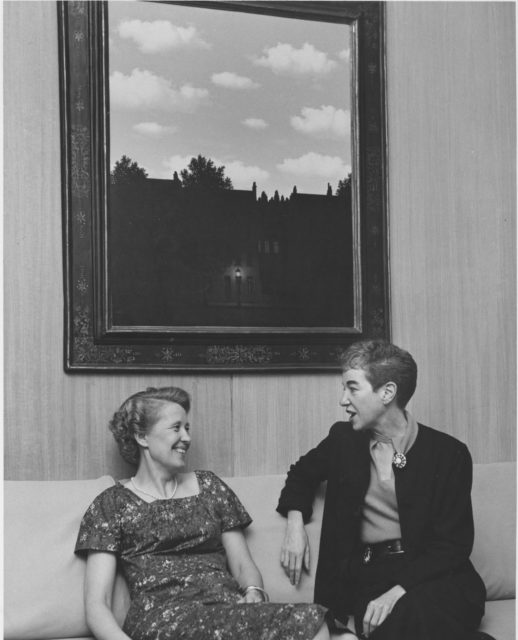

Dominique de Menil and Jermayne MacAgy speak under Rene Magritte's 1954 L'empire des lumieres. Photo courtesy Menil Archives, the Menil Collection.

Dominique de Menil and Jermayne MacAgy speak under Rene Magritte's 1954 L'empire des lumieres. Photo courtesy Menil Archives, the Menil Collection.

As they started, they established an art history department at the University of St. Thomas. They hired faculty down from New York, initiated lucky students as their assistants, and brought to the campus Ernst and Andy Warhol, who sometimes just showed up in class unannounced. In 1955, they hired Dr. Jermayne MacAgy, a curator and museum director who also became legendary for her taste, courage, and ambition. In 1959, she created a spectacular exhibition for Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum (CAMH) --- one of the many other museums in which the de Menils were always involved well before the CAMH was in its current home. MacAgy's exhibition was called “Totems Not Taboo” and displayed 230 non-Western sculptures and objects in the huge space of the MFAH's Cullinan Hall, where MacAgy built a “series of stairways, walkways, and passages” to order and augment the viewing space. They also invited the architect Philip Johnson to Houston because they planned to redesign the St. Thomas campus. He became their friend and designed their iconic house, which, looking back, was like a rehearsal for the building she and Renzo Piano designed to hold their art permanently.

They eventually moved their operation from St. Thomas to Rice University, where they established the Institute for the Arts and built two metal buildings that looked like Quonset huts—one called the Art Barn, the other (still standing) the Media Center for the film and photography programs they established. And just as they had invited famous painters to St. Thomas, they invited famous film directors such as Antonioni and Godard to Rice. Even Pauline Kael came to speak. At about this time, they also wanted to build a memorial chapel at St. Thomas in honor of MacAgy, who died suddenly in 1964. This eventually evolved into the Rothko Chapel, which opened in 1971 and which is one of the most significant parts of the visual record the de Menils left of their lives, generosity, and influence.

Most significant, of course, is the museum itself, the Menil Collection. She and Piano agreed on two essential things—that the building look smaller on the outside than it felt on the inside and that it be illumined by natural light. In discussing Reyner Banham’s book The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, Piano said : “It was about architecture made of light and immateriality . . . architecture [made] magic by things you don’t touch: atmosphere, light on multiple planes, a sense of depth, of distance.” It is interesting that these two Europeans affiliate themselves, unwittingly perhaps, with the deeply American tradition of Luminism. In American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America, Robert Hughes writes that the Luminists painted in the belief that “light turns matter into spirit.”

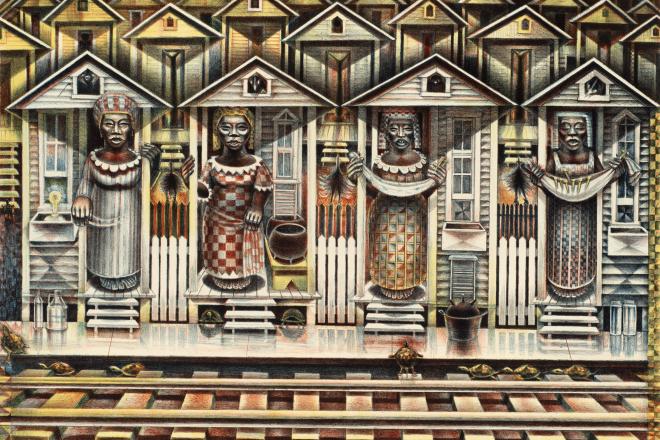

Second in importance is the Rothko Chapel. Rothko considered himself a religious painter—tragic and transcendental—and the de Menils agreed. The chapel is an experience antithetical to the light-filled museum, but it has also become a photographic backdrop for the de Menils’ involvement in civil and human rights, from John’s early sponsorship of the African-American Congressman Mickey Leland, who filled Barbara Jordan’s seat, to their friendships with the Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and President Jimmy Carter. When they acquired Barnett Newman’s “Broken Obelisk,” which they placed in front of the Chapel in perfect counterpoint, they dedicated it to the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At this time, they also published the first volume of The Image of the Black in Western Art; two more editions followed in 1979 and 1989, and the Menil Collection itself has been followed by the Twombly Gallery, the Byzantine Fresco Gallery designed by their son Francois, and Richmond Hall with the Dan Flavin light installation. Most recently, a new building designed by Johnston Marklee to house the collection’s drawings has opened.

Middleton reports few troubling incidents in the de Menils’ lives after they have survived the War and settled in Houston. There is the lingering question about the effects on the children that their long separations had and an unconfirmed rumor of an affair John is purported to have had. There is, however, nothing like the financial crisis that began around 1989. Dominique had felt the foundation was “hemorrhaging money” and was powerless to control it; her son Francois threatened to quit the board of directors; and then she hired Dr. Susan Barnes, the daughter of her old friend Marguerite Barnes, who was deputy director and chief curator at the Dallas Museum of Art. The museum staff was “wildly opposed,” Middleton writes, to Barnes’s hire, and she was excluded from staff meetings. Dominique felt forced to require the staff sign a “loyalty oath,” which closed no wounds. In the summer of 1990, Susan Barnes retired, and the foundation’s finances were eventually straightened out. Middleton reminds us that in the context of other oil fortunes in Houston, the de Menil Foundation’s $79 million was, ironically, “modest.” But the de Menil project proceeded.

Double Vision tells an engrossing, important, even exciting story that moves at a pace which sometimes seems exhausting. Middleton keeps everything as clear as possible by often repeating essential pieces of information to remind us of what he had reported pages ago. And one very important aspect of the book is its many pictures, of the dramatis personae, the houses, buildings and galleries they occupied, and of the works of art. In fact, this is one of the few books I can think of that has enough pictures—many spread throughout the narrative, and others in inserts of excellent color pictures of both the art and the places they occupied.

The book comes to an end with Dominique’s death, although it has already reported on elements of the story that occurred subsequently. It closes by quoting a love letter she wrote to John in 1931 at the time of their engagement. The last word of her letter, the last word of Middleton’s story is “dazzling.”