With Amazon’s recent rejection of Houston’s bid for the much vaulted HQ2, people across the region are fiercely debating where the Bayou City fell short. Our lack of regionally effective public transportation did us in! No, we don’t have a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation! Clearly, Harvey signed our death knell! If only there was a train to the airport! While we will never be sure why Houston was cut from the shortlist, civic leaders have already begun pondering how to make Houston a more attractive city for darlings of the innovation realm. With Mayor Turner calling for a summit of local leaders to address how Houston can become more competitive for corporate relocations in the future and and the just announced Midtown Innovation District, these conversations are coalescing into more specific plans for the future. While it is important to analyze what could be the shortcomings of Houston’s Amazon bid itself, it is also important to understand how local leaders would approach such planning efforts and benchmark whether the recommendations would be sufficient to position Houston to be more competitive in the future.

Fortunately, a group of civic leaders recently have gone through a planning process that addresses many of the issues that are relevant to this competitiveness discussion and could shed light on the types of recommendations Houston might follow. That planning process resulted in the recently published Plan Downtown.

While Plan Downtown is a remarkably ambitious and far-sighted document, the question is: does it go far enough? Does it prepare Downtown and Houston as a whole for the radical economic and technological changes already roiling cities? Are we heading in the right direction to continue attracting the businesses and talent that drives our thriving city? Below is a bulleted summary of my thoughts followed by the full analysis.

A Summary

- Plan Downtown could reshape not only the Downtown district but the direction of the city and region.

- Discovery Green, Buffalo Bayou Park, Cotswold Street Improvements, the Downtown Living Initiative, and other past efforts set the pattern for the new plan.

- A "Green Loop" with improved connections to the west, southwest, and south presents the most significant departure from the landscape Houstonians are familiar with. Pursued in tandem with the North Houston Highway Improvement Project, connections to the north need greater attention and commitment.

- The proposed cap over the freeways to the east of Downtown is very ambitious in scale. To serve as a major destination and to work well as a connector between Downtown and "EaDo" requires innovative design.

- Small-scale changes proposed at the street and bayou level could have a greater cumulative impact than the large-scale projects.

- While the plan makes an important step in acknowledging some disruptive changes on their way such as autonomous cars, shared work spaces, and more online retail, it does not anticipate the possible scale and risks associated with these disruptions.

- The proposed Innovation Corridor that gained momentum with Rice University's plan for the Sears site is an important first step to make Houston a technology hub.

- Admirable support for affordable housing in surrounding neighborhoods is not accompanied by specific goals for affordable housing within Downtown.

- On the whole, by imagining an expansion of recent gains in livability, Plan Downtown is evolutionary not revolutionary.

First Some Context

As both the geographic as well as symbolic heart of the city, Downtown Houston represents one of the first images Houstonians conjure when they think of their hometown. The Downtown skyline is etched into the collective consciousness as the emblematic statement of Houston’s identity. With no significant natural features to speak of, manmade structures substitute for an iconic peak, bay, or other awe-inspiring geographic landmark for the city. Its composition of skyscrapers also closely correlates to Houstonians’ notion that human effort, rather than geographical fortune, is at the heart of the city’s success. Even though other nodes in the region like the Medical Center and Uptown can boast bigger numbers of jobs, residents, or retail, Downtown continues to represent Houston in the minds of people across the region. Therefore, any attempt to shape the long-term development of Downtown can both influence as well as reflect the image and identity Houstonians have of their city. As such, understanding how Plan Downtown, the twenty-year roadmap for transforming Downtown Houston, proposes to reshape the district is important for understanding the potential direction of Houston itself.

Plan Downtown was the result of an eighteen-month planning process undertaken by the Downtown District to guide long-term development. It focuses both on the shape and structure of the district itself as well as its connection to the surrounding neighborhoods. In addition to input from over 1,300 respondents, a 19-member Leadership Group and a 166-member Steering Committee worked to shape the plan to determine the goals for Downtown’s future. As with any plan of its scope and scale, these stakeholders looked to address current conditions as well as anticipate future trends that could impact Downtown.

Plan downtown: Bagby street. Source: Downtown District.

Plan downtown: Bagby street. Source: Downtown District.

The idea that there should be a cohesive masterplan for Downtown Houston is actually a relatively recent concept. As late as 1995, there were no masterplans for how to comprehensively revitalize Downtown to become anything more than merely a collection of office and municipal buildings with the Theater District tucked into one corner. Early planning efforts conducted by Central Houston, Inc. founded in 1983, and Central Houston Civic Improvement, Inc., founded in 1984, focused on preliminary enhancements to specific areas within Downtown such as the design competition for Sesquicentennial Park in collaboration with the Rice Design Alliance (publisher of Cite) and its implementation as well as the Hermann Square beautification in front of City Hall.

These efforts were further buttressed with the creation of the Houston Downtown Management Corporation (HDMC) and its ability to levy property assessments to fund both ongoing maintenance and cleaning services as well as to plan and implement a series of neighborhood plans across Downtown. Other actors such as METRO, St. Joseph’s Hospital, and the Greater Convention and Visitors bureau tackled specific aspects of Downtown planning such as street improvements, creating a more focused medical campus, and the development of a large hotel to support the convention center.

In some instances, these independent planning efforts focused narrowly on their specific projects' goals and were not coordinated with each other. In fact, HMDC and its constituent property owners became so vocally opposed to a series of METRO proposed changes to bus service operations, they created an entirely separate planning effort to focus on property and pedestrian improvements. While these competing planning efforts exemplified the lack of coordination at a broader level, this friction ultimately led to different parties recognizing concerns beyond their narrow interests and realizing that the decisions they made would impact areas beyond their focus. This realization laid the groundwork for more integrated planning approaches in subsequent years.

Subsequent coordinated efforts to revitalize Downtown led to a transformation so dramatic, a Houstonian transported from the late 90s might not recognize the parts of the urban core today. A number of facilities, including Minute Maid Park, the Toyota Center, and the Hobby Center, created sports and entertainment anchors to draw both locals back to Downtown and attract additional convention business. An expanded convention center and the addition of the Hilton Americas further supported convention business. Streetscapes throughout Downtown also saw significant transformation with major projects like the Cotswold streetscape improvements in northern areas and the addition of enhanced pedestrian areas along the length of the initial METROrail line. The addition of Discovery Green, and, to a lesser extent, the upgrades to Market Square and early improvements along Buffalo Bayou created regional or local destinations for outdoor activities. The recent completions of the Marriott Marquis and the Purple and Green METROrail lines, the enhancements to the George R. Brown Convention Center, and the increases in housing resulting from the Downtown Living Initiative should spur further activity in the Heart of Houston.

Yet though all of these transformations represent a significant improvement to the countless barren parking lots of yesteryear as well as a fairly comprehensive restructuring of the urban fabric, they seemed to bring Downtown Houston up to relative par with other urban cores across the country without aiming for a higher standard. While all of these projects represented significant investments in buildings, streetscapes, and infrastructure, many of them seem relatively safe, and there are few truly inspiring projects among them.

In her 2011 assessment for Cite of Downtown projects, Kelly Klaasmeyer graded them as a B+ and lamented the unwillingness to take risks or push the envelope. Though many projects are massive in scope, they are not all particularly memorable in character. Projects focused on enhancing the pedestrian experience like the Cotswolds and Buffalo Bayou projects and the upgraded sidewalks along Main Street did result in a significantly improved public realm experience. Discovery Green has become a recognized destination in Houston and truly anchors the eastern area of Downtown. But many of the architectural projects seem more successful at achieving functional goals than significantly raising the bar for design. As Klaasmeyer noted in her article, good enough isn’t good enough. While some of these developments, such as Discovery Green, have significantly raised the bar for projects in Houston and changed the way civic leaders think about urban spaces, their cumulative results did not yet launch Downtown Houston to become one of the great American urban cores. However, they did provide a solid foundation for continued improvements and begin to make people think of Downtown as a destination in Houston rather than just a place people commute to for work.

Planning for Current Challenges

With these previous efforts as a starting point, the new Plan Downtown offers an opportunity to make Houston’s core a truly great urban center. But in many ways, how well Plan Downtown approaches this opportunity is actually a reflection of many planning issues that were important over the last twenty to thirty years rather than the coming decades. Essentially, business as usual. Neighborhood connectivity, mixed-use districts, walkability, transit-oriented design, low-impact development, infill projects, and multimodal mobility were basically the goals of many projects completed in the last twenty years. The plan’s authors seem to have spent a great deal of time developing solutions that address many of the same issues that civic leaders and professionals have been discussing for years and do not stray far from recently pervasive perspectives of urban planning. While the solutions reflect a great deal of careful and considered thought, there are no significant surprises in the proposals outlined in the plan, nor does it attempt to significantly push the envelope when looking to the next twenty to thirty years.

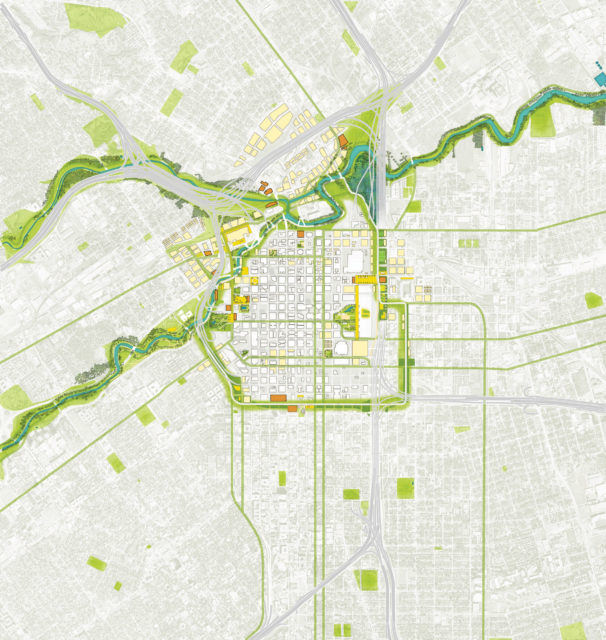

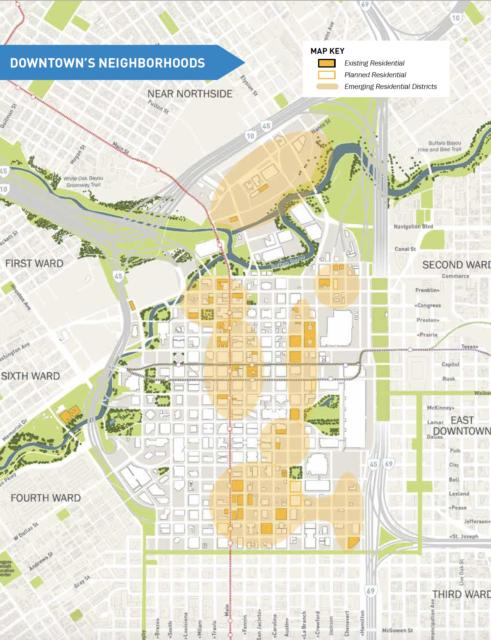

More directly connecting Downtown to surrounding neighborhoods is the most expansive and visible proposal in the plan. The plan envisions what its authors call the Green Loop – a trail, park, and public space system – to encircle downtown and then recommends a number of specific strategies adjacent to that loop to stitch Downtown back together with the urban fabric of surrounding neighborhoods. In conjunction with TxDOT’s 24-mile, $7 billion, decade-long North Houston Highway Improvement Project (NHHIP) infrastructure project to completely reroute or reconfigure all of the freeways that currently encircle Downtown, the plan develops separate solutions that address the connections to the north, south, east, and west.

Green Loop. Source: Downtown District

Green Loop. Source: Downtown District

Reimagining downtown's west edge. Source: Downtown District

Reimagining downtown's west edge. Source: Downtown District

Downtown's green loop: Pierce Street. Source: Downtown District.

Downtown's green loop: Pierce Street. Source: Downtown District.

Pierce street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

Pierce street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

Downtown's green loop: Bayou step. Source: Downtown District.

Downtown's green loop: Bayou step. Source: Downtown District.

Bayou Steps existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

Bayou Steps existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

The connections to the west, southwest, and south present the most significant departure from the landscape Houstonians are familiar with. The plan, as well as the NHHIP, envisions the almost complete removal of the Pierce Elevated beginning at the southwest corner of Downtown. In much of the newly reclaimed area that connects Downtown to Midtown, the plan proposes developing pedestrian and bike-oriented greenspaces as well as reconnecting the street grids currently cut off by the existing freeway. The plan does recommend evaluating options for preserving a portion of the Pierce Elevated. The section of abandoned freeway would be converted to an elevated park with the spaces below geared towards flexible neighborhood programming.

For the areas across Buffalo Bayou from Downtown adjacent to the City’s current municipal courts and jail, the plan proposes further developing that area as an enhanced core of municipal activities by locating critical fire and police department activities there, developing an enhanced justice complex, and creating cultural attractions such as a state-of-the-art library, a cultural diversity or history museum, or outdoor music venue to the area. The plan further recommends extending METRO’s Purple and Green Lines through this area to enhance their connection to public transit as well as open the door for further METROrail expansion along Washington Avenue.

While these modifications address many of the negative aspects that the elevated roadways between Downtown and these adjacent neighborhoods currently present, the solutions they propose demonstrate varying levels of success. The expansive civic complex envisioned for the area adjacent to the Old Sixth Ward would enhance the vitality of an area that currently lacks cohesion and presents an opportunity to create a positive and appealing public face for civic engagement. Extending METROrail lines into this civic complex and allowing for further expansion to points further west enhances mobility and connectivity not only for Downtown, but for other neighborhoods within Houston’s urban core. However, the plan seems to maintain the jumble of overpasses and bridges that cut off Downtown from the recently completed Buffalo Bayou Park.

The recommendation to evaluate partially retaining a portion of Pierce Elevated does not seem fully resolved. While cities across the world have envisioned their own version of New York City’s wildly successful High Line, the existing Pierce Elevated structure does present unique opportunities for redevelopment. Some people have latched onto converting the roadway into a park. While such a floating park would provide a unique experience in a city with a complete lack of elevation, what exists below might provide a more compelling opportunity. In a city with brutally harsh summers and torrential downpours, the large expanse of continuous shade and cover provided by the roadway could become a linear public space that is occupiable nearly year-round. As someone who started his daily commute for years at a bus stop underneath the Pierce Elevated, I very much welcomed the protection the structure provided in the scorching summers and torrential downpours. Creating engaging and dynamic spaces programmed with a variety of temporary and permanent activities and amenities under such a continuous concrete canopy could become a compelling attraction for both neighborhood residents as well as people from across the region. Enhancements to the structure could also transform it from a barrier separating Downtown and Midtown to becoming a gateway between the two. Some people have argued that redeveloping the Pierce Elevated as a public space is far too costly to ever be financially feasible. Yet the significant increases in property values around the High Line do support further due diligence. Transforming the Pierce Elevated into a grand and iconic landmark could attract the investment in the area necessary to underwrite the project. Leaving just a portion of the Pierce Elevated seems to be a safe solution that avoids the risk of developing a more envelope-pushing solution.

The modifications to connect Downtown to neighborhoods east are also considerable. To a large extent, the plan envisions creating an expanded and continuous sports, entertainment, and hospitality district to support a further expanded convention center. This district effectively envelops EaDo into an extension of Downtown by proposing a highway cap over the reconfigured I-45/U.S. 59 corridor. The highway cap that stitches the two neighborhoods together would become a multifunctional civic and recreation space to further enliven the district. Public plazas and pedestrian zones would extend it to adjacent amenities like Discovery Green and the Columbia Tap trail. Additional convention center hotels proposed for the area would further increase the hotel room count in the District.

Reimagining downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

Reimagining downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

The highway cap could be a welcome contrast to the freeway barrier that currently separates Downtown from EaDo as anyone who has actually tried to walk from EaDo into downtown can readily attest. The configuration of the highway cap in the renderings appears to resemble something similar to, though dramatically larger than, Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park: a simple, flat deck covered with a combination of vegetation, hardscape, and structures. Its boldest move seems to be its immense scale. In this instance bolder solutions could create a more effective connection between Downtown and EaDo. For example, using Atlanta's proposed Park Over GA400 as a model might offer an even more compelling configuration than the simple, flat deck proposed in the plan. With its dynamic and undulating surfaces that connect the disjointed parts of the Buckhead area together, it provides a more stimulating configuration than a plain covered deck. The solution also reduced development costs: by leaving portions of the submerged freeway open to the sky, many of the costs associated with the lighting, ventilation, and life safety systems required for a continuously covered, below grade freeway were eliminated. Such an undulating structure could focus more attention on areas where a stronger connection between Downtown and Eado is needed - such as between Minute Maid Park and the Houston First building - and limit it where there is less of a need - such as immediately behind the convention center itself. As local leaders work with TxDOT to develop this deck park, they should aim for solutions that simultaneously stitch Downtown together with EaDo and create the unique and exhilarating attractions that draw in visitors from across the region and beyond, yet still knit an urban fabric that supports the day-to-day activities that make Downtown a neighborhood as well as a destination.

Downtown's green loop. Source: Downtown District.

Downtown's green loop. Source: Downtown District.

Highway existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

Highway existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

The recommendations to connect the northern edge of downtown to the Near Northside present the least successful connections proposed in the plan. While the plan envisions significant developments within the area between Buffalo Bayou and the current alignment of I-10 - including partially rerouting the bayou itself - it largely ignores what would happen on the north side of the freeway corridor created by the NHHP project. Other than evaluating a realignment of the Union Pacific rail line in that area and indicating a few road connections into Downtown, the plan is relatively silent on further enhancing connections with this northern neighborhood. While weaving the neighborhoods together in any effective way might prove exceedingly challenging given the considerable barrier the NHHP freeway project and rail lines present, the plan should more strongly advocate for TxDOT to significantly enhance connections to the Near Northside, even if the configuration of those links are not fully resolved at this time.

Reimagining downtown's north edge. Source: Downtown District

Reimagining downtown's north edge. Source: Downtown District

North edge vision. Source: Downtown District, Google Map

North edge vision. Source: Downtown District, Google Map

Beyond these larger scale solutions, the plan includes recommendations for smaller scale interventions and reconfigurations that policy, design, planning, and development professionals have been grappling with over the last few decades. For example, the recommendation for infill development would lead to a more continuous urban fabric. Prioritizing different modes of transportation for different streets within the Downtown grid has the potential to enhance mobility and create viable alternative transportation networks. Low Impact Development would work to address localized flooding issues. Transit oriented development along the Green and Purple lines would enhance the areas surrounding METROrail stations as well as potentially increase ridership. Designated transit lanes could help increase mobility. More visible, activated, and accessible connections to Buffalo Bayou would lead to a softening of the hard surfaces that seem to dominate Downtown. And enhanced streetscapes populated with human scaled building facades, outdoor seating, street amenities, and landscaping would not only create more attractive public realm experience for pedestrians, it would create a more cohesive and distinctive district with a more neighborhood scale.

Walkability improvement: Caroline Street. Source: Downtown District.

Walkability improvement: Caroline Street. Source: Downtown District.

Caroline Street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

Caroline Street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

While all of these smaller scaled interventions would not be as readily recognizable as something more apparent like replacing the Pierce Elevated with a verdant esplanade, they would have a greater cumulative impact if fully implemented. Though relatively sedate in nature, their impact would significantly enhance the overall character and texture of Downtown and create a more cohesive and relatively pleasing environment. While nothing about these restrained recommendations would make Downtown truly unique within the region or beyond, they would create a district that is subtly, but perceptibly, improved in relation to many other parts of the city. Given the fact that many of the challenges these recommendations would address have been present for decades, implementing them would be a significant improvement to Downtown and help transform Downtown from being merely a district within the city into a neighborhood in its own right.

As with the interventions in Downtown of the past, all the proposed solutions look at transforming Downtown at multiple scales. Should civic leaders be able to make some of the larger scale changes and knit Downtown together with its adjacent neighborhoods in 10 to 20 years, Houstonians of today might be just as surprised with the extensive changes to Houston’s urban core as a Houstonian from the 90s would be surprised by transformations that we live with today. Continued and focused attention of creating more appealing streetscapes and pedestrian experiences would continue to enhance the overall fabric of the district. Yet as with interventions from the past, the bulk of the solutions, whether significant in scale or not, seem relatively safe in nature.

While the changes outlined in the plan overall represent distinctly positive improvements, there is little boundary pushing or risk taking here. While many of them may be as transformative as the reconfigurations of Downtown over the last twenty years, transformative is not the same as boldness. Many of the solutions seems as though the direction of Downtown Houston had already been set, and these proposals merely steer along that same course. And we seem to accept this business as usual course without reflecting on whether it is the right one.

Planning for Future Challenges

While the plan focuses most of its attention on solving many of the challenges of Downtown’s past, addressing the challenges of the future seems to be an area that the Plan does not focus on quite as thoroughly. Once again, the plan seems to stay in safe territory and does not speculate on a future that looks wildly different than the world we see around us. This business as usual approach may not serve Downtown well in a world that seems to be constantly changing. The proposals outlined seem to be an extension of the world we have been living in for the last 20 years rather than anticipate the potentially seismic shifts that could profoundly disrupt many of the assumptions designers, planners, civic leaders, and other professionals use to develop plans like Plan Downtown. In some cases, the disruptions are already here. As much as the advent of smartphones and social media have dramatically changed the way people interact with each other in the new millennium, other forces – whether based on technology, changing business models, or other seismic shifts – could have equally disruptive effects in the future. And while Plan Downtown addresses some of the threats and opportunities these shifts might create, it is not clear that the plan recognizes the full potential magnitude of their impact.

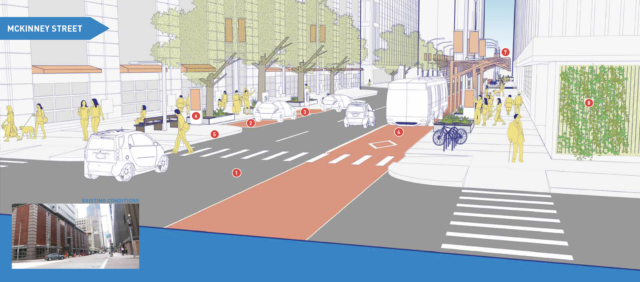

Plan Downtown does acknowledge the potential impact of technology to a certain extent. Autonomous vehicles represent one such advancement that could be a paradigm shift both for mobility and urban planning. The plan recognizes this potential impact and identifies some very preliminary solutions for how to incorporate autonomous vehicles into the urban fabric. Given the numerous unknown effects, the plan’s recommendations for developing an autonomous vehicle policy framework and organizing a transportation technology working committee are prudent. Such a committee would clearly need to determine solutions so that autonomous vehicles do not overwhelm street operations. For example, the autonomous vehicle/service zones indicated in the some street sections highlighted in the plan appear scaled more for a restaurant valet stand rather for than for thousands of commuters that would potentially empty onto the streets at rush hour. Understanding how to accommodate those commuters is essential for mobility to remain unimpeded. There is clearly a need to focus more attention on the basic but fundamental practicalities of how autonomous vehicles will transform our use of the public realm. And we will need to focus a great deal more attention on that potential transformation in the future.

Street of the future, downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

Street of the future, downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

McKinney street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

McKinney street existing Condition. Source: Downtown District.

The plan also acknowledges the serious issues of housing in Houston’s core and the potential for housing problems to become direr in the future — especially in the wake of Harvey. It includes a proposal to collaborate with adjacent neighborhoods to create a central city housing strategy. The recommendations admirably include supporting inclusive, mixed-income housing; striving to allow communities to shape the directions of their neighborhoods rather than market forces; developing transit corridors and pedestrian/bike trails to increase connectivity; developing the basic elements like schools, neighborhood retail, and open spaces that increase the livability of communities; and supporting efforts to address homelessness issues. These recommendations address issues that clearly need solutions but include very few specifics as to the next steps. The plan once again plays it safe and does not commit to any goal that might be difficult to achieve. While it is important to work with the adjacent neighborhoods, it is equally important for Downtown’s leaders to also address inclusive housing issues within the district itself and not assume its neighbors will solve all of its issues for it. The recent Houston Downtown Living Initiative demonstrates that creating incentives can help spur residential development. Further incentives could address the issue on a more inclusive manner. Without more explicit ideas for how to solve housing issues, the plan provides not as much guidance as would likely be required.

New neighborhood clusters, downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

New neighborhood clusters, downtown's east edge. Source: Downtown District

The plan recognizes the potential impact of connected infrastructure to support new development. With recommendations for expanded WiFi access and smart street lighting systems, the plan proposes some very preliminary solutions for enhancing data collection and smart controls for improved district operations and increased mobility. And yet, there is potential for smart technologies to much more profoundly change Downtown life beyond timing of traffic lights. Toronto’s recently announced partnership with Google’s corporate cousin, Sidewalk Labs, to use technology to completely reimagine the city experience presents the type of initiative Downtown’s civic leaders should consider. By measuring and observing how people inhabit a city at a level far beyond anything previously undertaken while working to balance privacy concerns, teams at Sidewalk Labs propose using data, rather than lofty design principles, to help guide planning decisions to continually improve the urban experience. Whether used to locate a park bench, a grocery store, or a public green space, they see the collection of data as key for making planning decisions that are fast, iterative, and based on observed facts. The city itself becomes the new testbed for technology. Though Plan Downtown does acknowledge the need for creating a more connected district, it largely ignores the how data and technology could completely transform the planning process to allow a much more meaning experience for Downtown’s denizens.

Beyond these examples of technology, Plan Downtown bases a number of its recommendations on underlying market assumptions about corporate office, hospitality, and retail spaces that have driven real estate development patterns in the past. It is not clear, however, how much new and disruptive business models might upend those assumptions. Co-working space providers like WeWork – which recently announced that IBM would fully occupy one of its locations in Manhattan rather than sign a traditional lease – could upset how traditional corporations and firms lease the blue-chip skyscrapers of Downtown as well as the financial instruments developers use to finance such trophy buildings. (The plan identifies creating collaborative spaces like what WeWork offers but envisions them as the “office of the future” to support startups and incubators rather than established firms.) Platforms like AirBNB would likely never fully replace the 4,000 additional hotel rooms including two large convention center hotels that the plan recommends, but they may reduce the quantity of additional rooms needed and provide a broader variety that certain travelers expect. And while the plan does hint at the future of retail, it is not apparent how clearly defined shopping places and ground floor retail that the plan recommends align with consumers’ dramatic shift to online merchants like Amazon and the rapidly changing retail landscape. All of these shifts could have major impacts on how places like Downtown get occupied. While it is impossible to fully understand today the repercussions these shifts could have, not fully acknowledging their significant potential impact on the real estate sector as a whole as well as not outlining a process for adapting to them could be one of the riskiest moves in the plan. A more prudent move would be to clearly recognize these potential disruptions and lay out the ways the plan might adapt to them in the future.

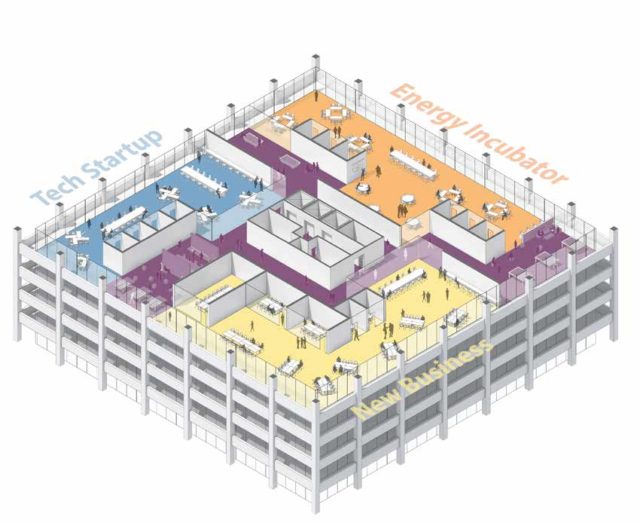

The plan does look to harness the future by using innovation as a catalyst for economic growth as well as a focus for planning efforts. The plan calls for the creation of an innovation district that looks remarkably like the one just announced anchored by the old Sears building in Midtown. It outlines the prerequisite flexible and creative working environments to house startups and incubators, the much-needed venture capital and angel investors, the partnerships, the programs, the collaborative ecosystems – all the commonly identified elements for creating such a district. Yet these are all recommendations that cities across the country are pondering - and likely included in their recent proposals for Amazon’s HQ2. And yet, serious questions continually remain for these types of efforts: do these relatively obvious recommendations represent the correct mix of ingredients for fostering innovation or should such a district be a precursor to much more daring and transformative initiatives? Should we reorganize existing assets, programs, and partnerships in a way that allow new ideas to be created and harnessed or do we have to create completely new institutions and organizations that can catalyze innovation and jump start Houston’s entrepreneurial spirit?

When New York City saw itself losing ground to Silicon Valley in the innovation game at the beginning of this decade, it held a competition to create a school for engineering and applied sciences. It offered three pieces of property and $100 million to academic institutions from across the world with the best proposal. The recently opened first phase of Cornell Tech on Roosevelt Island that resulted from that process not only houses a potentially world-class technology academy, it also brings industry into the campus to catalyze the type of technological advances that can make New York City a center of innovation. The University of Texas’s recently scuttled campus south of the Astrodome was intended to be a similarly game changing institution. Given the boldness of Cornell Tech and the abandoned University of Texas initiatives, it is hard to imagine how the relatively modest solutions recommended in Plan Downtown could create the conditions necessary for Houston to become a globally recognized center of innovation. While the new innovation district is likely a positive and useful first step to solving Houston’s innovation challenges, it could become a key ingredient for much larger and bolder efforts to catalyze innovation across Houston. Striving for something greater should be a goal Houston’s leaders should aim for.

"Office of the future." Source: Downtown District

"Office of the future." Source: Downtown District

A New Direction?

As people across the region begin to take stock of what went wrong with the failed Amazon bid and envision how Houston needs to adapt to attract the other innovation powerhouses that will be the driving economic forces of the future, Plan Downtown provides a good benchmark for the types of proposed recommendations that might come from that planning process. As such, it is also useful to take a step back from the individual recommendations and look at the proposals together to identify how effectively they address issues like innovation as a whole. To do that, it is important to ask more fundamental questions about the plan. Do the plan’s recommendations just lead to physical changes, or will there be a recognized change to Downtown’s way of life? Will Houstonians begin to inhabit the district’s public and private spaces differently? Will Downtown become a thriving, self-contained neighborhood with its own unique culture or will it continue to serve as merely a destination for activities related to work and play? And most fundamentally, how will the proposed transformations change Downtown’s identity in the minds of Houstonians and non-Houstonians alike? This last question is one that the plan seems to address the least. And given the recently failed Amazon bid, it is the kind of question Houstonians should be asking in our city more often.

In many ways, the plan’s recommendations reinforce Downtown’s current identity as Houston’s business and entertainment core. The plan mostly relies on Downtown’s existing core elements – a concentration of corporate office buildings, the City of Houston and Harris County municipal complexes, the Theater District, and the convention center district – and provides recommendations the district in the same direction it has been heading for decades. While the proposed innovation district might seem to add a new direction for Downtown, in some ways, it merely substitutes tech workers and entrepreneurs occupying Downtown’s office buildings for oil & gas workers. So even the one area where a new direction is proposed, the recommendations do not seem to go far enough to lead to significant change.

More broadly, the cumulative impact of the plan’s recommendations seem to represent no significant risks. The envelope remains firmly intact. The plan’s recommendations do not seem audacious enough to truly launch Downtown on a new innovation trajectory. Though the plan’s recommendations are numerous, they seem to follow a relatively risk-free approach that relies more on following many past decisions rather than confront future challenges head on. Should the recommendations be implemented, Houstonians would not likely view Downtown significantly differently in the future than they do now.

In many ways, Plan Downtown, crafted by dedicated and hardworking professionals, civic leaders, property owners, and other key constituents, seems eminently achievable. Its solutions are rational, realistic, easily imaginable, are absolutely congruent with planning efforts of the past, and would further strengthen Downtown’s position as the region’s key economic, governmental, and cultural center.

Yet, if we are to truly aim for a new direction and become the daring and more innovative city that can compete effectively on a world stage, goals of planning efforts like Plan Downtown may need to lean more towards being aspirational than readily achievable. While true pie-in-the-sky solutions often become irrelevant, setting aspirational goals can stretch expectations and push people beyond their comfort zones. Setting aspirational goals also introduces an element of risk: there is the possibility that goals may NOT be reached. But failure is a possibility for anything that is truly innovative. If we want to foster a culture of innovation in this city, our planning process should reflect that fact, include ideas that push the envelope, and allow people to become more comfortable with taking risks. Once we become accustomed to taking risks, being good enough will no longer be enough. And since a masterplan represents merely a roadmap for the future and not a set of steps we are explicitly bound to, there is little harm in setting goals that might seem beyond our grasp yet push us to achieve more. There are countless innovators across the city making profound strides in energy, medicine, and aerospace. It is time that planning make similar strides. If we want to be known as a city for risk-takers, we need to take risks with our city plans.

However, the specific goals of making our city a stronger hub for innovation are merely smaller pieces of a much larger conversation about what makes Downtown as a district or Houston as a city attractive on a broader level. While the individual strategies necessary to attract the next Amazon HQ2 are useful to focus on, creating a more livable city is a more compelling argument for enticing both the companies AND people that allow the region to thrive. And, in many ways, focusing on what attracts people is even more important than what attracts companies. The Downtown Plan is right to focus on many human-scaled interventions at the street level and grand projects like a gargantuan deck park. The balance of smaller moves for creating an active and exciting street-life filled with people with large-scale moves that could catalyze change for the whole region is the biggest contribution that Plan Downtown makes, in very crucial ways, for transforming Houston into a more attractive urban center. Still, the small and big moves could be more daring in implementation than shown in the masterplan.

Whether through physical solutions from the past – such as well-designed streetscapes and public spaces – to the digital solutions of the future – such as user-friendly, smart infrastructure – focusing on enhancing the day-to-day urban experience would yield the largest civic dividends for investments in areas like Downtown or the Houston region more broadly. While an abundance of technology jobs plays a key role in attracting people to innovation centers like San Francisco, Portland, or Seattle, it is their underlying livability that established them as hubs in the first place. Focusing on livability in places like Downtown, therefore, becomes a critical strategy on par with – or even more critical than – more visible solutions like an innovation district for positioning Houston as an innovation hub.

The Amazon snub may temporarily have focused city leaders’ attention towards narrower solutions that address what they perceive as Houston’s shortcomings. However, in the long term, creating the city where people enjoy living creates the most compelling argument for making Houston an attractive destination – whether as an innovation hub or not. Including solutions for how to achieve that goal is the most successful aspect of Plan Downtown. By reflecting on the past but, just as importantly, daring to look at the future, future plans must continue the work of transforming Houston into the livable city that residents – both longtime and yet to arrive – will enjoy for generations to come. Ultimately, we need to be audacious enough to look beyond the temporary setback the unsuccessful Amazon HQ bid represent, and keep an eye on creating a more livable city that sells itself.

José Solís is the founder of Big and Bright Strategies, which specializes in sustainability, risk mitigation, and project management for architectural and planning projects.