On a bright Saturday last March, the Rice Design Alliance hosted its annual tour. This year’s focus was “H20uston: Living in Floodplains,” and the tour opened six structures to the public—four houses, one townhouse, one historic commercial building—that all negotiate how to inhabit flood-prone grounds. A thousand visitors explored one or more of these locations and learned about different ways design can mitigate the impacts of flooding. It was a month of flood investigation, as weeks earlier, experts gathered in a civic forum to discuss flooding from various intersected professional disciplines. Videos from these talks are now available online.

Five months later, Harvey struck. Now the city is faced with the consequences, and will be addressing them for a long time. Cite magazine, a publication of the Rice Design Alliance, asked me to look at how the architecture featured on the “H20uston” tour fared during Harvey. Most buildings were in areas that did flood but they, along with their occupants, emerged intact. Unfortunately, the house in Meyerland, a 1965 Brooks and Brooks design, sustained damage. In the past, the terrazzo floors handled a small amount of flood water, showing that material choice can improve resilience.

What about the other buildings on the tour? I spoke with three occupants who generously shared their stories. As Danny Samuels suggested previously on Cite, and as this article will reveal, newer houses constructed to current building codes handled floodwaters much better than the original housing stock. As suggestions cohere into long-term plans, it is clear that stricter controls on new construction, amidst other more transformative programs, should be implemented. “Building, hereabouts, has traditionally been a form of stealing,” mused Larry McMurtry in the late 1960s, perhaps critiquing the housing developments that, half a century later, pose the greatest flood risks. Surely a house can be many things, but for thousands of Houstonians during Harvey, a few feet of elevation was the difference between having to evacuate yourself and welcoming neighbors who escaped into your house.

Linkwood

Jenna and Chad Arnold have lived on Linkwood, two blocks south of Brays Bayou just inside Loop 610, for nearly a decade. A few years ago, facing a long list of structural repairs to their 1951 ranch house, they decided to demolish and built new. The materials of the existing house were donated to Habitat for Humanity and the couple requested that every tree on the property be kept. Their architect Brett Zamore designed a 3,500-square-foot house faced in dark brick and light stucco that supports open interiors and a large exterior deck. Prized objects were given careful consideration; for example, a piano from Jenna's grandmother proudly sits in the open stairwell of the home. The floor structure of the residence, which was completed about a year ago, sits roughly four feet above grade. Regulations for new construction stipulate that the bottom of the lowest horizontal structural member must be eighteen inches above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The Arnolds' home was built an additional six inches higher.

During Harvey, this height made all the difference. Early Sunday morning, the Arnolds awoke to a call from a neighbor who was experiencing flooding in her home. Jenna watched her husband step off the porch and sink waist-deep in water. Chad helped a number of neighbors escape, and soon people that they recognized but don't know well were swimming over to their house. Later on Sunday, the Arnolds had nineteen people gathered in their house. Two big dogs made their home on the upstairs porch and a cat was stationed in every bathroom. Soon, neighbors wrapped in towels looked out at the flooded neighborhood. Boat owners navigated the shoulder-high waters in their vessels and plucked the remaining families from roofs and attics. At night most guests slept upstairs, as Jenna was concerned with the waters rising into the house. Chad slept downstairs with his hand on the floor to ensure he would wake up if water entered the house. After midnight he was awoken by a man outside in an air boat with a thick Louisiana accent; he was a member of the Cajun Navy, patrolling Linkwood to see if remaining residents needed any help.

On Monday morning, the waters had receded and residents returned to check on their houses. For the next week, Jenna and others helped direct clean-up crews to houses in need. Of the 140 houses in the Linkwood neighborhood, 120 were flooded. Thankfully residents were safe. “There's a newer house pretty much on every street and every new house was taking in people from the ranch houses,” she said. Here, the archipelago of new construction provided safe havens during the flood event and served as a base for coordinating clean-up in its aftermath. It is unclear how Harvey will transform the social fabric of Linkwood. Jenna said some neighbors already have “For Sale” signs up, but others plan to build new, and still others await pay-outs that will enable them to renovate.

Reflecting on the design of this house, Zamore stressed that it is important to keep the foundation skirting as open as possible. Instead of vents in a more typical closed wall that could retain moisture under the house, he used mesh on three sides of the foundation that allow water to pass through, ensuring the crawlspace will air out quickly. The Arnolds' house remained dry, though water flowed under the house and nearly reached the bottom of the floor structure. The garage is at grade; inside it is faced using cement board, not drywall, with smart vents installed in the walls, a material choice that makes clean-up easier. Unfortunately, the garage still filled with two feet of water, and Jenna lost her car. All in all, the Arnolds emerged as helpful survivors, and are grateful to Brett Zamore's expertise in designing for a flood-prone lot. “We've been so pleased about some of the decisions that were made about our house,” Jenna said. Their house shows “there's a way you can build that will survive this crazy Bayou area.”

Shirkmere

Jacki and Andrew Schaefer moved into their new house the week before the Rice Design Alliance tour last March. Jacki is a Rice Architecture alum and teaches a Building Information Management (BIM) course at the school during the Spring semester. She completed some initial sketches herself for the house before working with architect and Rice Architecture professor Nonya Grenader to design the house.

Jacki and Andrew's two-story, L-shaped residence sits at the end of Shirkmere in a residential pocket inside the Loop and west of White Oak Bayou. Its primary strips of windows open north towards the neighborhood. Southern openings are minimized both for thermal reasons and to turn away from the adjacent railway and industrial lot, as townhouses are planned for the site but haven't been built (though the plots are visible on Google maps). The house is bigger than the previous one on the lot, but because so much paving was removed, the impervious coverage actually decreased.

The design takes the typical but important flooding precautions. It is raised to the minimum required height and smart vents are used to ventilate the crawlspace. Throughout, architectural split-face concrete masonry units (CMU) are used as a foundation skirt, including in the garage and in the demising wall between the garage and the elevated house. There is no drywall in the garage, which again makes clean-up easier.

The couple has two small children and, worrying about an extended power outage, they evacuated to Dallas on the Thursday before Harvey's arrival. Jacki kept in touch with her tight-knit group of neighborhood friends via their Slack channel. Andrew, who works in optimization in the oil and gas industry, had installed cameras at the house, so the family watched Harvey batter their piece of Houston until their house lost internet access. As with the house in Linkwood, newer houses served as places of refuge until neighbors could be evacuated to higher ground. One neighbor, wading across the street, snapped a picture, included below, and sent it to Jacki. They also own the house next door, a ranch on a slab; Jacki thought for sure it was gone.

They waited without an update until Tuesday, when a neighbor was able to check on their house and the one next door. Miraculously, both were dry. The family, still in Dallas, immediately began raising money online from friends and, a few days later, drove a U-haul truck full of supplies back to Houston. Arriving back at their house, they immediately began assisting neighbors in clearing out the muck.

Many residents are now faced with the decision of whether and how to rebuild. It can be stressful, as families just want to get back into their houses. But for most, the FEMA or insurance payouts are a big chance to do some house improvement. “You don't get that opportunity, with these funds and the demolition work already done,” Jacki said. She has given some advice, mostly to be thoughtful in analyzing their family's flow and usage of space. Instead of building bigger, build smarter and with more flexibility, she says.

At night the neighborhood is dark, with few lights on and not a lot of AC units running. Already there are vacant lots—“FEMA lots,” in the neighborhood's parlance—from Hurricane Allison that serve as gathering places for the community. There may be more in the coming years as homeowners decide to relocate. In rebuilding, Jacki hopes people think about the “large-scale implications” of their individual actions, and to not add more impervious coverage to the city. It is “hard to get people to care about the public good,” she notes, but it becomes very real when it happens to you: “I hope people get smart.”

Sunset Coffee Building

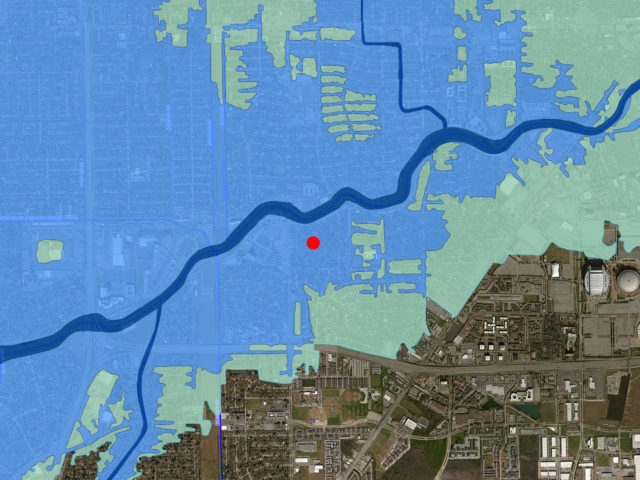

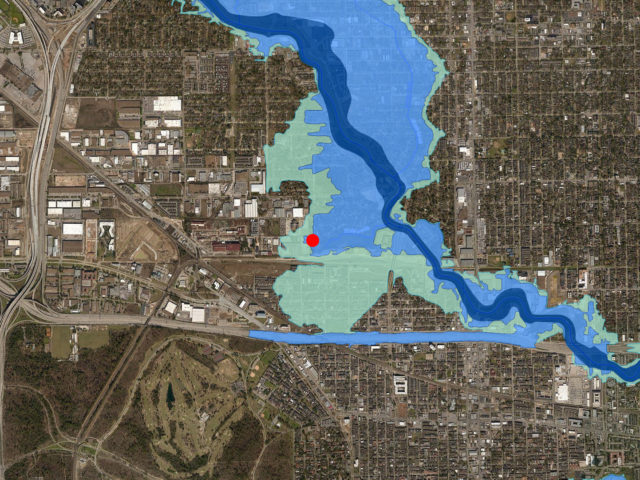

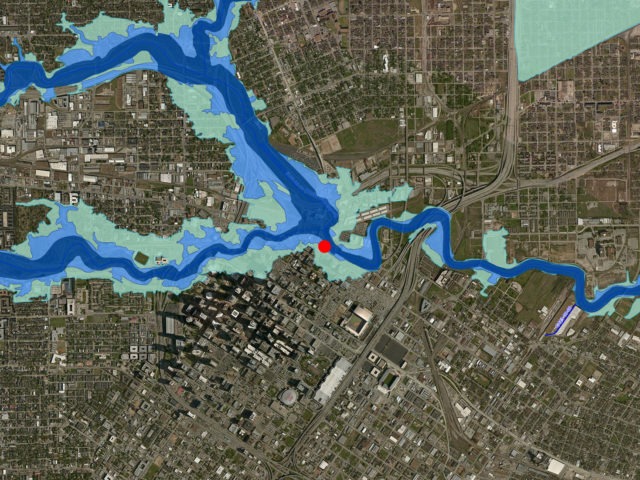

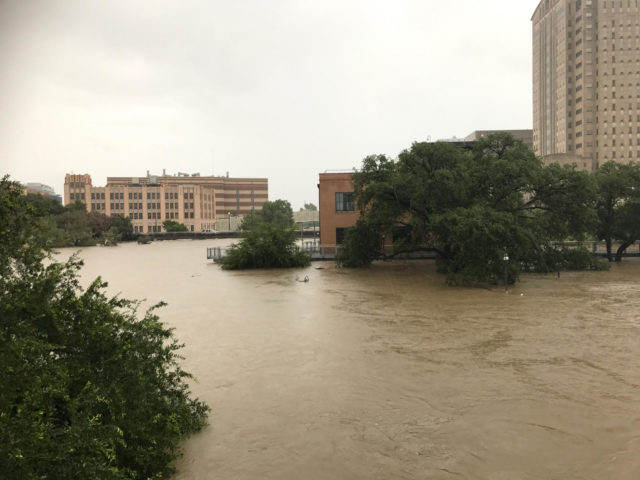

Next to Allen's Landing, the Sunset Coffee Building was both the only commercial and oldest structure featured on the “H20uston” tour. It has been significantly renovated by Lake|Flato and BNIM and now serves as the home for the Buffalo Bayou Partnership. (Colley Hodges recently wrote an in-depth appreciation of the Sunset Building for Cite.) The design of the renovated structure allows its first level to flood: there are durable finishes, and mesh security gates allow the water to move through the space. Located at the confluence point of the Buffalo and White Oak Bayous, the area was inundated with high, fast, and debris-laden waters, as the images show. All sources indicate that the design performed as anticipated.

“We knew it was coming,” Anne Olson told me, of Harvey. The staff moved exhibit materials to the second floor and secured the elevator on an upper floor. But there are always issues. The grease trap filled with water, thermostats need to be replaced, and the elevator shaft had five feet of standing water at the bottom, causing electrical issues. Security cameras mounted on the building filled with water and malfunctioned. The fire alarm went off for four days, making the area sound like a war zone, even catching the attention of a CNN reporter. Still, water didn’t crest into the offices on the second floor. (It was almost this high during Allison.) Shortly after the waters receded, the building was habitable again.

Soon, the Partnership’s staff and volunteers were hard at work cleaning silt and debris out of their parks, including deep deposits in the Houston Police Officer’s Memorial. Trails downstream largely weren’t affected, though serious erosion took place, to the extent that the BBP is considering increasing the depth of the land the Partnership purchases for easements, Olson said. The BBP lost a dock and boat, but the pair was found in the Ship Channel by the Coast Guard, still roped together. (Rice Crew, who rows along this stretch of the bayou, was also impacted.)

Olson said the intensity of this flood will have an impact on the master planning effort underway for the eastern portion of Buffalo Bayou. She remembered that Allison hit in 2001 during the master planning stages for the first section of improvements, and after that the “whole hydrology and flooding aspect took on this greater role in the plan.” Other proposals that were shelved due to cost may be reviewed; one example is a diversionary canal from White Oak to the lower Buffalo that was studied in 2002 but never funded. Olson said one flood model predicted the improvement would reduce flood waters by 5.5 feet in this stretch of downtown.

During my visit in late September, the waters still ran high and fast. On the narrow docks, a pair of workers hosed silt back into the bayou. Behind the building, a Bobcat scraped silt from the rear courtyard. Above my head debris remained woven into the chainlink fence enclosure of the fire stair. Having a café tenant with seating throughout the courtyard and a kayak rental vendor would complicate flood preparation matters in the future, but the building—and the BBP—will be ready.

As with the residential projects seen on the “H20uston” tour, the Sunset Coffee building is a testament that good design is not mere surface aesthetics: it is a deeper structural concern that can wind up saving your life. (Or, at the least, the memory-laden objects you collect and hold dear.) The BBP’s Rebecca Leija and Anne Olson told me their insurance adjuster said the Sunset Building, built in 1910, was well-suited to handle floods due to its height and angle relative to the bayou. Sure enough, in plan the building is set at an angle to the bayou's flow, presenting a corner to floodwaters rather than a flat face. And, its east façade breaks slightly, perhaps to further reduce the surface area “seen” by floodwaters and therefore reduce their force on the walls and foundation. Good design works and then it keeps working. This is an important message to carry with us as post-Harvey rebuilding efforts move forward.