Cities define themselves by their skylines, collections of anonymous highrises made distinctive by an icon or two that stand out. We know those icons – the Space Needle in Seattle, the Empire State Building in New York, Philip Johnson’s Bank of America Center in Houston – but we rarely pay much attention to those other tall buildings that fill out the picture.

Houston Mod’s latest book, Constructing Houston’s Future: The Architecture of Arthur Evan Jones and Lloyd Morgan Jones (2017), is the fifth publication in its ongoing project to document Houston's modern architectural legacy. Author Ben Koush asks us to look more closely at the anonymous mid-century buildings in the Houston skyline, giving them a story and a context that challenges our tendency to let them fade into the background. Koush, an architect himself, brings an architect’s appreciation for details to his subject. It can be tough to love the concrete frame of the 1953 Melrose Building, located at the corner of Walker and San Jacinto Streets, but Koush’s admiration for its technologically precise and aesthetically pure horizontal bands of concrete sun shades shines through.

Koush splits the book into two sections, one a series of short essays that includes profiles of the architects and the developers they worked with, and the second a series of 50 short building histories that suggest the full scope of Jones’s work in commercial and residential architecture. Jones was clearly a skilled technician and architect, but his real coup was having the savvy to partner with real estate developers like Kenneth Schnitzer and Gerald Hines. Through those partnerships and a shared corporate vision, the Lloyd Morgan Jones firm became one of the most prolific architects in the city – their fingerprints are on Rice Stadium and the Astrodome, Kinkaid School and the Houston Baptist College, the Houston Natural Gas Building downtown and “Enserch” Tower in far west Houston.

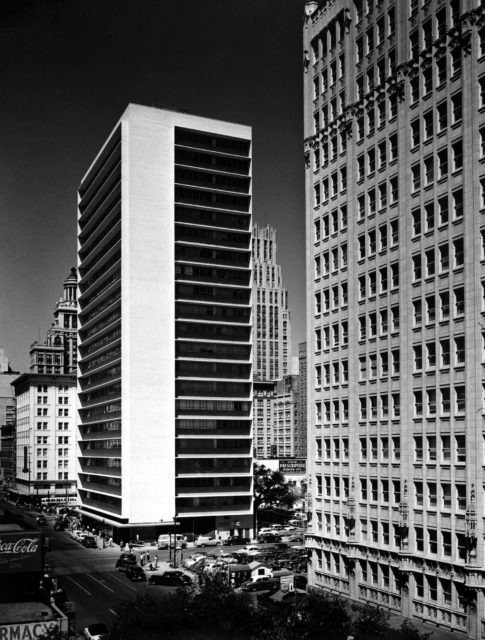

A central goal of this book is to nurture a more widespread curiosity and admiration for the mindset of midcentury architects, who embraced technological and material experimentation in ways that we don’t understand well today. Koush presents Jones’s clean-lined, hard-edged, and efficient commercial buildings as examples of a “commitment to…progress” that reflected a deeper belief in Houston’s future as a leader of industry. The Galvestonian, a condominium on the beach, becomes a “minimalist sculpture,” the American General Building on Allen Parkway, a restrained concrete frame tower in a park-like setting, is “regal.” These minimal towers are much underappreciated. Just looking at the buildings already lost, like the Americana Building, with its bold terracotta tile base, suggests the need for much more public discussion of the values and vision of mid-century modern architecture.

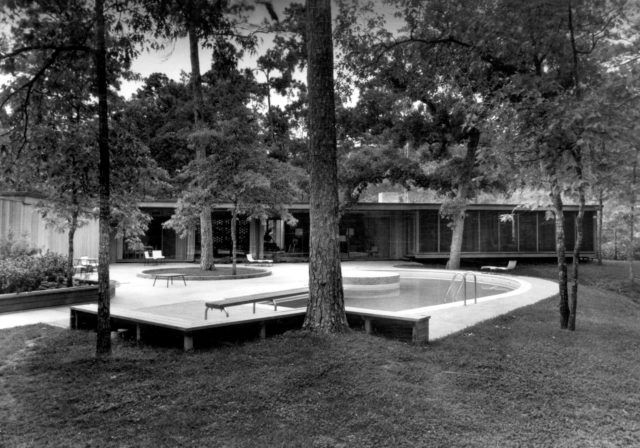

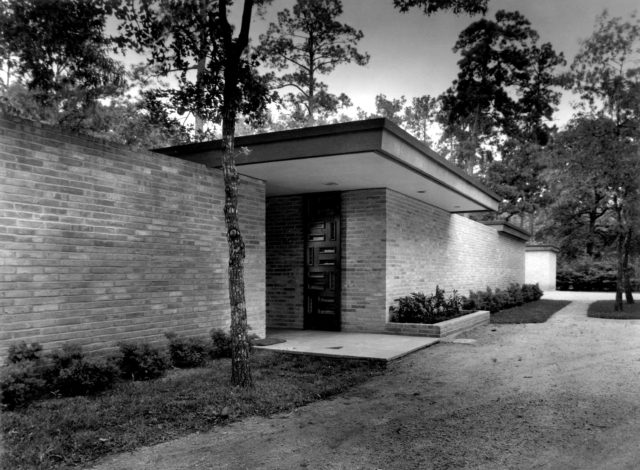

The conversation is even more overdue in discussion of residential architecture. Jones was part of a generation of architects that explored the one-story courtyard house as particularly suited to hot Houston and its shady piney woods. While our visions of mid-century modern houses are often shaped by images of California and its perpetual 75-degree days, the achingly lovely Liese House (now demolished), created a Texas model for outdoor living by opening all its rooms to the outdoors and to a large courtyard made possible by its large suburban lot. Steenland House (also demolished), used Houston’s sprawl to its advantage, spreading across its lot and underneath the trees, keeping out of the sun and providing shaded patios and courtyards. We lose too many of these inherently modest but still elegant houses to tear-down syndrome and today’s tastes for more overt – and more vertical – expressions of domestic pride and success. As Houston contemplates the future for its “Mad Men” suburbs, entire neighborhoods filled with the low-slung, ground hugging houses typical of the 1950s and 1960s will be faced with difficult choices about how to adapt to an increasingly hostile and flood-prone landscape.

While the word “preservation” can raise the hackles of those who view its goals as an insidious brand of governmental overreach, at their best preservation advocates help guide conversations about civic values and history. Preservation is about shared story-telling, about letting the places we have built and used across generations provide a shared landscape to grapple with the complicated meanings of the past. If we blindly demolish our way into the future, we are left lost, the footprints that brought us to the present erased. While Koush’s book is largely documentary, introducing us to the people and places touched by the Lloyd Morgan Jones firm it, along with all of Houston Mod’s admirable work advocating for the Astrodome and mid-century modern neighborhoods throughout the city, jump starts that much-needed conversation.

Perhaps more importantly, post-Harvey, urgent questions about Houston’s rapid and decentralized development are finally being asked outside the usual architects’ and planners’ offices. The fragmented, episodic, and seemingly unsupervised nature of highway construction, suburban office tower development, and new subdivisions blossoming overnight is often ascribed to Houston’s lack of zoning. But, of course, the problems of sprawl and poor environmental planning and land use are not confined to Houston.

Constructing Houston’s Future provides a tantalizing glimpse into the mechanisms of private wealth and closed door real estate development that drives this kind of urban growth and provides material to allow us to ask a lot more questions about how cities might grow instead. The future that Jones helped build prioritized private development and profit above civic engagement and it left a legacy of sleek, well-crafted machines for capitalism. Greenway Plaza, on Southwest Freeway, and Allen Center on the western side of downtown, required seamless, behind-the-scenes manipulation of civic planning processes to implement massive superblock projects that closed city streets and created suburban green lawns populated by elegant glass towers. Each of these individual projects, conceived as unrelated, individual tiles in the city’s mosaic, contributes to an increasingly unsustainable urban landscape. The reality of this kind of development process, in which private capital defines civic processes and priorities, led Houston to its failures of civic form and infrastructure in the twenty-first century. Buy this book – and line up for the sequels that ask bigger questions about how architects, planners, developers, and policy-makers have created the cities we inherit from them.

Kathryn E. Holliday is Associate Professor and Director of the David Dillon Center for Texas Architecture at the University of Texas at Arlington. Ben Koush is a frequent contributor to Cite; Constructing Houston’s Future grew from an article he published in Cite.