Giovanna Borasi directs the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), one of the world’s leading architecture research institutions and museums. In this interview, she speaks about the operations of CCA, including its projects, exhibitions, and positions. Also addressed are 2020’s twinned crises—the pandemic and a renewed call for racial equity—and how these concerns will shape the CCA in the years to come.

A version of this exchange with RDA's Executive Director Maria Nicanor appears in Cite 102. If you’re not already an RDA member, receive your copy by becoming an RDA member or purchasing an issue here.

Maria Nicanor: I always like to know more about how friends and colleagues got into architecture and design. Often times the path to an architecture-related field is not a straight one. You’re trained as an architect but have spent most of your career as a curator and writer. After first joining the CCA first in 2005, you were appointed as its new Director last January following Mirko Zardini’s tenure. Where did you grow up and what experiences shaped your journey towards an interest in architecture and the built environment?

Giovanna Borasi: It’s nice indeed to look back at how and why things happened the way they did, even if initially planned differently. I was drawn to study architecture because it is a precise discipline. At the same time, it is responsive to daily life and societal change. I like the struggle between precision—building with a larger purpose and planning for the long-term—and, at the same time, this need for improvisation, as you’re constantly challenged by life in and of itself.

While I was studying architecture with Pierluigi Nicolin, who was and still is the Editor-in-Chief of Lotus, I decided to work for the magazine. I thought this was a good experience before launching myself into the practice. Eventually, Pierluigi invited me to stay another year, as Lotus published only four issues per year and I had worked only on two issues. Every year I asked myself whether I should go back into practice. In the end I stayed eight years. That’s also where I met Mirko Zardini, who then was an editor at the magazine. Lotus was a thematic magazine, and each issue proposed a theme for discussion. The idea of approaching architecture through lines of investigation or themes clearly comes from that experience.

The passage between editorial and curatorial work was smooth for me. The first show I really assisted in for the research and curatorial direction was Asphalt: The Character of the City in 2003, curated by Mirko for the Triennale di Milano. It was a learning experience about unexpected ways of looking at society through the lens of the banal.

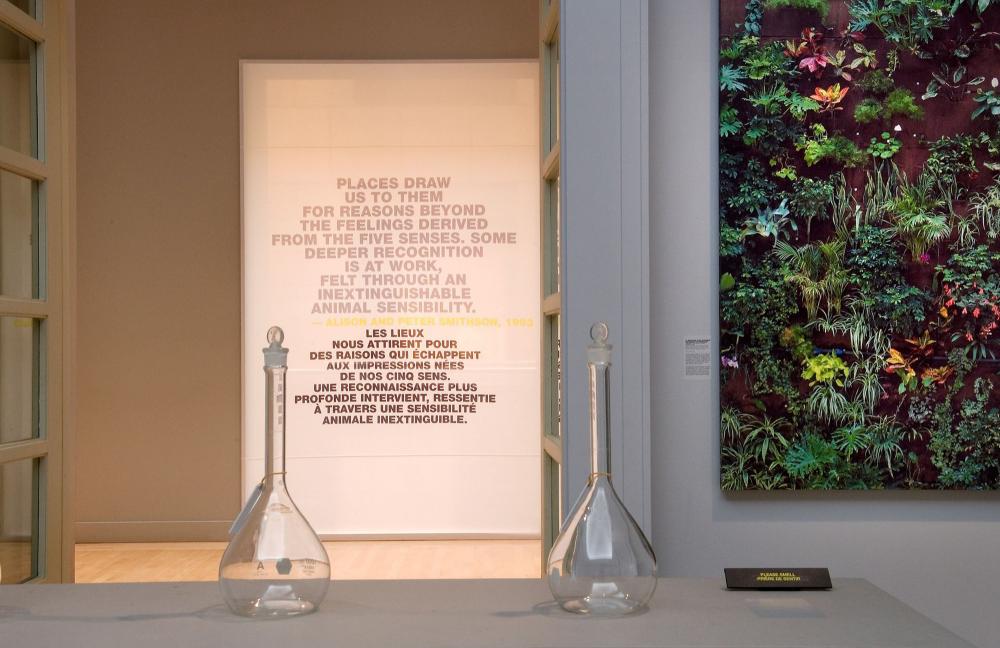

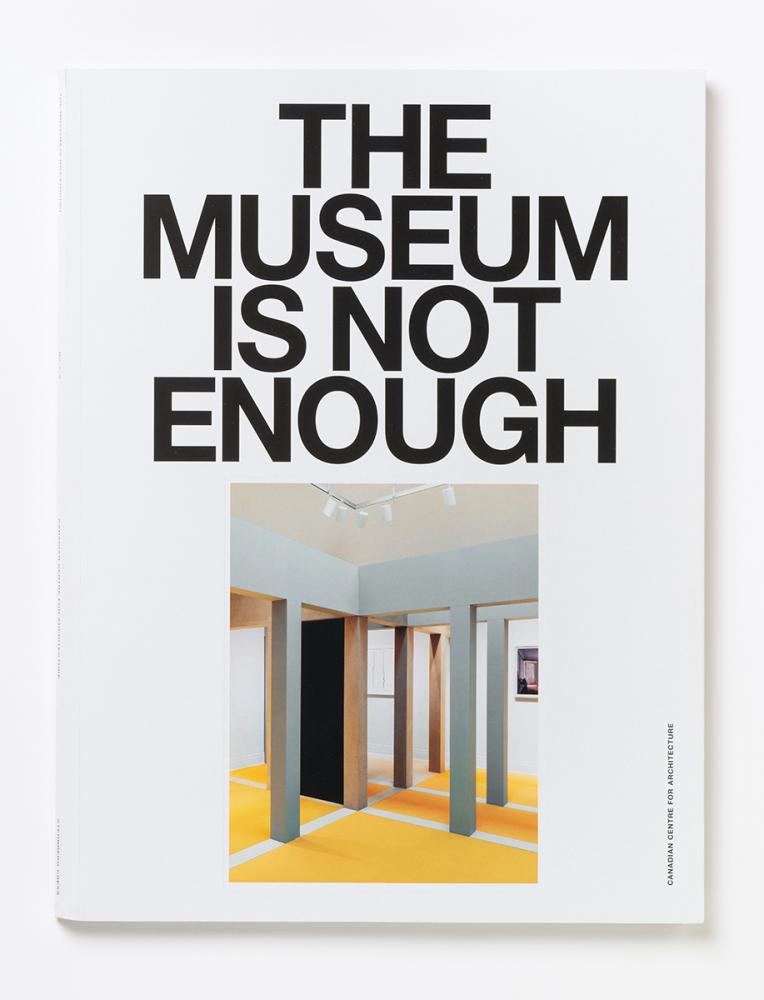

Following that exhibition, which relied a lot on archival material from the CCA, the institution asked Mirko to rethink the show for presentation in Montreal. He came up with idea for Sense of the City, and I worked on that through contributing to research and the definition of the curatorial concept. Between 2004 and 2005, I travelled several times to the CCA and eventually applied for the position of Curator, Contemporary Architecture. Since then, I have been continuously connected to the CCA, rethinking and contributing to different sets of thematic investigations that I explored with Mirko since my arrival in 2005. In our 2019 publication, The Museum Is Not Enough, we call these topics “grey zones”—unexplored areas in society that we address through the lens of architecture. It’s a way to bring architecture back into the current discussion on contemporary issues and to consider its role in responding to societal issues.

As for my interest in architecture and the built environment, what initially drew me to architecture is how it can be used to understand society. Whereas anthropology is focused on the study of society and social formations, I think that architecture has the capacity to go beyond this. Architecture isn’t simply a lens through which to understand the contemporary world; it has the capacity to foresee different approaches to the future. Therefore, I see a lot of my curatorial work as almost architectural projects. Every show I work on not only raises questions about a topic, but also offers a proposal or activist agenda for possible ways of framing or tackling the issue.

The CCA was founded in 1979. Phyllis Lambert conceived of it as a bit of an outlier, a different kind of organization from which to discuss architecture. How do you keep that sentiment alive today? How does the CCA remain “of its time,” in a moment where there are many more channels through which architecture is discussed and presented than back then?

The CCA was created to be a new form of institution. At once museum and knowledge-producer, with its own publication and research departments supported by the collection, all working together to create a place where ideas are formed, discussed, and questioned at an international level. Since the beginning, the idea of being an international center was a way of acting as a point of reference to a diverse and dispersed audience–even in a pre-digital era when sharing ideas was limited to publications and travelling exhibitions.

Being an international center gives us the opportunity to ask ourselves how to be relevant, not only in relation to the time and place we live in, but also in the sense of questioning for whom—which public—we are working. The CCA’s insistence on building a dialogue with a larger audience than a local or national one, compels us to constantly ask ourselves how to be relevant and how to be connected with the times we live in.

There are more channels and platforms today where architecture is presented, but to me only a few of them have clarity in their efforts. If in the past architectural magazines or architectural schools or other sorts of institutions were authoritative in some of their answers, I now find the territory very blurred. I think we’ve passed from institutions to individuals that have become a sort of reference. In today’s world, the impact of your voice is no longer related to the scale of your institution: You can make your message heard independently regardless of who or where you are. Still, I remain fond of institutions, even if I think that institutions don't exist per se—institutions are always comprised of people. I believe in the capacity of institutions to ask—and even sometimes to answer—big questions.

The CCA is also in dialogue with the practice of architecture, and it has two ways of dealing with this. On the one hand, we observe what architects and practitioners are working on; we don’t theorize, but instead we gather the different ideas we find and re-frame them in a set of questions that go beyond the practice. And on the other hand, we observe what’s inside these questions on a societal level to reinsert architecture into the discourse.

If I think about being timely as a question of curatorial and editorial practice, or research for example, we need to be much more anticipatory. We need to collect things today that we think will be relevant in ten years. We need to anticipate what the requests and aspirations of researchers and scholars might be in ten years, in order to be “on time” for them. It is an interesting game to constantly pass between current and future needs, while acting today. At the same time, the CCA’s forty-year legacy and the long history of its collection allow us to look at the past to understand what is relevant to look at today.

The work you do at the CCA is framed within a large institution at a national level that has a global curiosity and output. RDA, for instance, operates at a much smaller, yet very crucial scale, and from within the framework of an academic institution, as we’re the public programs and outreach arm of an architecture school.

Larger institutions can achieve certain things, while smaller organizations, can play very different roles. Where do you see these smaller organizations in the larger picture as conveners of many with an interest in the built environment? What can they achieve for their communities that larger institutions can’t? And how do you see the balance of local vs. global content in places like CCA in Montreal, or the RDA in Houston?

The question of scale is key to an institution. I really like the scale of the CCA because it's big enough to take on an ambitious project. When I say big, I don't refer to the number of people, the resources, or time we have, but to the diverse expertise involved in undertaking a large project with confidence. At the same time, we are small enough to avoid typical institutional issues like siloed mentalities, departmental territories, and things like that. Some of our units consist of only two or three people. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we all worked on the same floor in the CCA’s six story building; for now we work from home. We operate at a scale where discussions and decisions can happen at a meeting of just two or three people. These are all healthy proportions for capability and performance.

Smaller institutions always maintain a certain curiosity, humbleness, or nimbleness. They have a desire to do more. It’s a very good state of mind to push the institution and push everyone to accomplish something special. But it's not only the scale, it’s also the culture of the place: Not being self-congratulatory or resting on our laurels is also part of the success of the institution and its smaller scale.

We have no other choice than to consider our work for a community that is larger than the one in Montreal or in Canada, simply because of the variety of issues we are addressing.

We are working with formats that are new to us to expand the way we produce, reflect, and distribute knowledge. For example: together with two invited architectural practices, Rural Urban Framework in Hong Kong and 51N4E in Brussels, we’ve realized The Things Around Us, which addresses the question of context and the new “ecology of practice,” to use the words of Francesco Garutti, the project’s curator.

Another effort is CCA c/o, a series of temporary initiatives that are locally anchored in different cities worldwide. The effort partners with independent curators, architects, journalists, and editors from these different geographies. These actions are a tool to reveal issues of general relevance that emerge from different contexts. In two versions we’ve collaborated with Kayoko Ota, a curator in Tokyo, and Martin Huberman, a curator in Buenos Aires, to establish a research practice that connects us to communities that we would not otherwise be able to reach and ideas that go beyond our Western worldview. And with a collection that spans from the Renaissance to born-digital material, we are in conversation with scholars that have very different priorities and who are writing different histories of architecture.

Because of the CCA’s mandate to work with a range of formats and to address a variety of subjects, albeit very niche ones, we will never be able to limit our dialogue to the local public in Montreal. Rather, we must always address a dispersed audience of researchers and collaborators.

In contrast to many other institutions, the CCA does not consider itself an educational institution. We don't even have an education department anymore. We don't need and don’t want to teach or educate anybody. This relieves us from any kind of service to the local community. That said, we have plenty of free public programs for students and families, and we invite and welcome any kind of visitor to do research on the collection. But I think the idea behind what we do is a way of connecting to a broader audience.

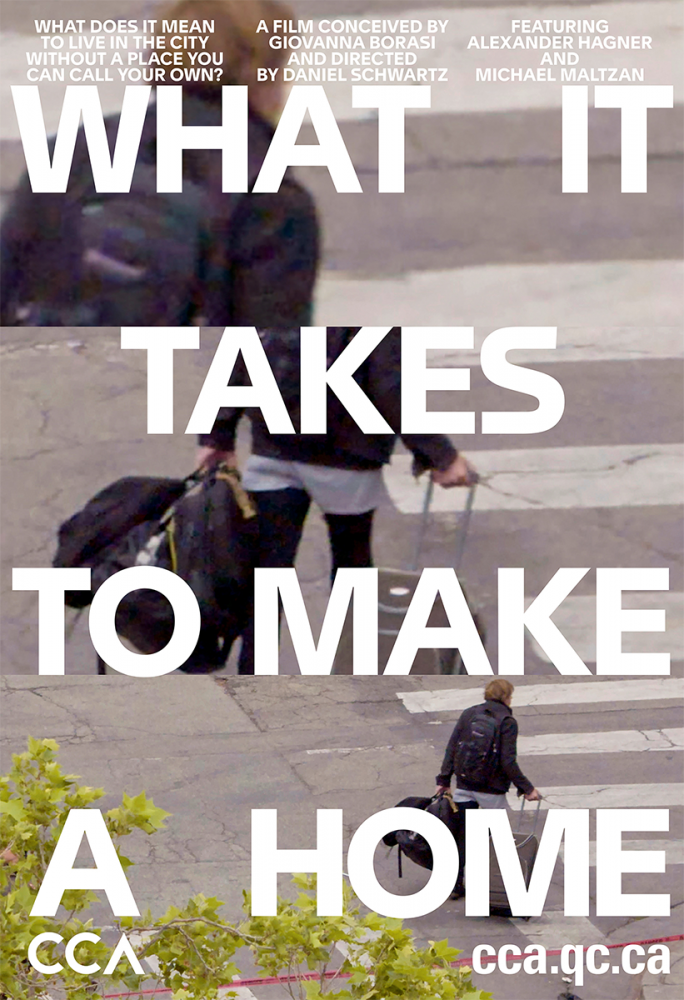

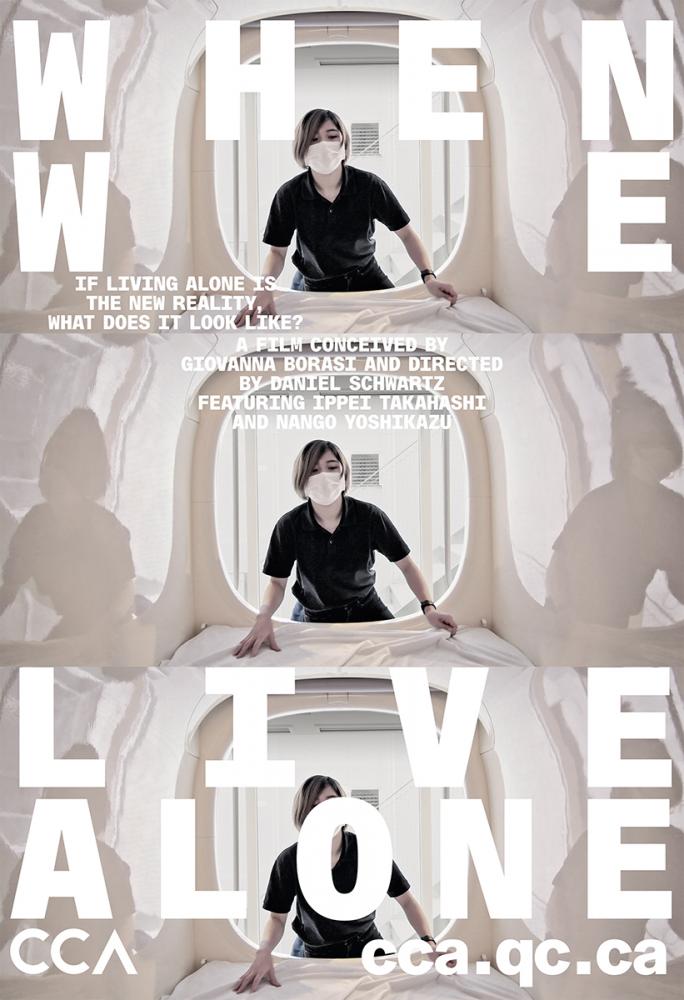

For example, consider the new series of three documentaries we’re working on now: The first one addresses homelessness (What It Takes to Make a Home), the second one (When We Live Alone) is about single people and the rising number of people living alone, and the third forthcoming one will be about the issue of an aging society. In doing something like this we want to talk to a larger audience beyond the one in Montreal. But at the same time, homelessness is an issue in Montreal. So we address a topic and broaden the question, but we also try bring it back to the core of what we do and analyze from that point of view.

Maybe this is just how everyone operates now. To me, it's very clear that you shouldn’t separate publics. You shouldn’t assume that in Houston you do one thing and then in more broadly in Texas or the United States you ask other questions. As an institution you might not have the energy and the resources to do this. But I think you have to continuously zoom out from your local context and then zoom back in—it’s a constant dialogue. That’s how we live in our hybrid physical-digital world today.

I’m very interested in formats and the ways in which we all engage with and learn about architecture, design, our cities. Some people will learn more from a party or a program carried out with humor, while others take more out of a traditional lecture or formal symposium, for instance. Can you tell us more about the formats you work with and how you approach content in unconventional ways? This is especially important in our culture of constant entertainment and experiential distraction. Inevitably our exhibitions, publications, and programs compete for attention with other mainstream channels.

I agree. Formats can be interesting tools with which to develop architectural discourse and to engage people. I think the question of formats can be considered from two points of view.

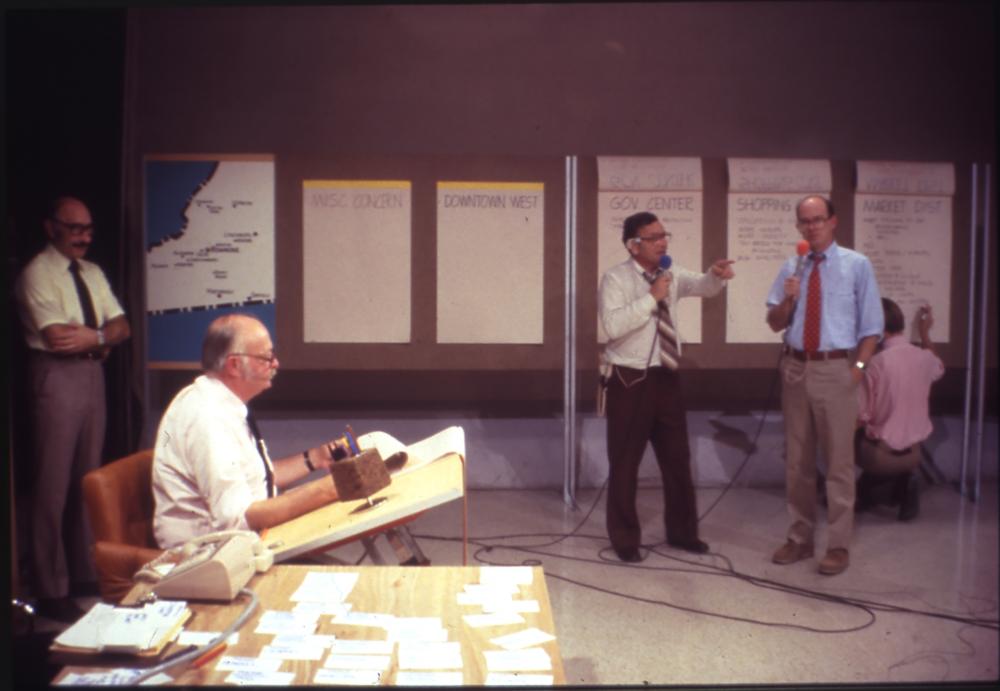

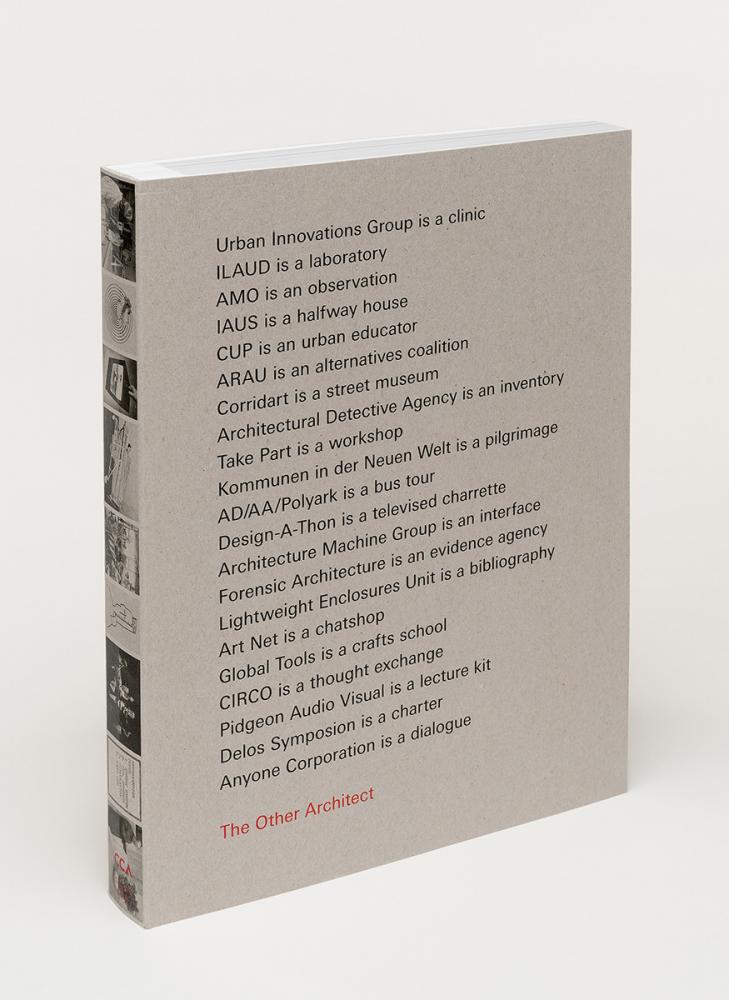

One relates to ways of learning; this is something we reflected upon at the CCA when we worked on an exhibition about The Open University and the experiments they did on television in collaboration with the BBC. This relates to the use of TV as a format for design by Charles Moore, an example I also researched when working on The Other Architect. Through using TV programs to teach the history of architecture and by taking the perspective of the viewer, the program wasn’t about how you teach, but about how you learn. So, this idea of learning is crucial when we think about formats.

Clearly formats can also be used as a productive way of framing an argument, or focusing only on an aspect of it; to inform, to provoke a discussion; or to let people think for themselves when they leave the format itself behind. The expanding role of curators is not only about curating the content but also about curating the format itself. This can be a very sophisticated way of shaping content.

At the same time, it’s fundamental to pair the right format with the right content. I don’t believe that formats are good per se. I think that they can be appropriate for a certain scope. At the CCA, we are constantly exploring formats, and when we’re not inventing new ones, we are diversifying the ones we have. I think we use all the curatorial opportunities available to us between exhibitions and publications, short, long, digital, or not.

The questions are always: What public do you want to reach? What reaction do you want to elicit? What content do you want to communicate? Then there is the question of timespan, how will the content be used in the long-term, and in which context. It’s a fantastic opportunity to consider and to explore, in order to advance the content even further.

Sometimes it makes sense to go back to very simple formats, like informed guided tours or well-researched and constructed bibliographies. I don’t think we should reject past formats as uninteresting because they might lack the entertainment value of more recent or experimental formats.

We’re also constantly re-examining our own approaches. Last year Lev Bratishenko, the CCA’s Curator, Public, led a program called How to: disturb the public. The program invited a group of young aspiring curators, researchers, and architects to think about ironic ways of challenging institutions and to consider new ways of actively engaging the public. The group created a “cookbook” that can be used by other institutions to shake up their formats. We’ll be using one “recipe” to open up internal meetings to the general public. We just finished the latest installment of How To with How to: reward and punish, a program that looked at architectural prizes, their legacy, and how to repurpose them to possibly build a different framework for architectural discourse.

Formats are useful if you consider them as tools, and if you always keep in mind what you want to accomplish with them. It’s not a question of whether they are good or bad, but of whether they are the right tools for what you want to do.

We all live in cities and in spaces, and so we all have opinions about them regardless of our background and expertise. In that sense, our work as architects, designers, curators, engineers, should aspire to a meaningful engagement with the public. In your view, what role should architectural organizations play in discussing the public, societal changes that are defining our era? These might not necessarily seem like architectural problems in the traditional sense of the term. Is architecture/design uniquely placed to solve some of those problems? Or can we merely ask questions?

This is something that we’re trying to do at the CCA: to show the relevance of architecture and urbanism to everyone—to show that everyone has a stake in it. But I am not sure it is right for every institution, or if they should do so to the same degree. It depends on the priorities of the institution. There are valuable institutions that have a very specific focus but still manage to have a broader reach. The Center for Land Use Interpretation, is one example; it responds to contemporary issues, but it also has a long-term focus and span to its work. I really like what they do. Sometimes they ask questions about social events, but that’s not their focus. I think we need a diversified institutional landscape in which each organization helps us diversify how we look at architecture and engage with topics in different ways.

We should draw a distinction between architectural institutions and the practice of architecture. I think the responsibility of an architectural institution like the CCA is to be in a place of friction between a society that is organized in a certain way, or requires certain forms of care, on the one hand; and, on the other, architects, policymakers, or decision-makers that are meant to deliver on these requirements. By occupying the middle space between these two sides, the institution can play an interesting role in pointing to what is relevant, asking the right questions, and provoking people to think differently.

Then there is architecture itself. Does it need to ask these questions? I’m not sure. I think it should deliver some answers or some paths to enable others to arrive with some answers. I think architecture has a projective opportunity, and in doing so somehow it also poses questions. Ultimately a project has to imagine a future scenario besides the brief that is given. In putting a future scenario on paper you are forced to ask these questions at the same time as you deliver answers. These answers become the object and the subject that another institution can reflect upon—not to judge whether they are right or wrong, but to indicate possible directions.

When tackling societal issues, for us it’s always important to always do it through the lens of architecture. Which of its diverse tools can architecture put in place to address societal issues? Answers still come from the capacity to read a place, the capacity to work with the resources available, to work with different materials to create a space or a form that has embedded societal values, and the capacity to create rituals. All of this is connected to space. There is—or there should be—a great sense of responsibility in architecture in that it has the capacity to influence societal issues. These issues are always embedded in architecture, even if they aren’t addressed directly.

We started this conversation some months ago prior to the current pandemic the world is experiencing. Now, in the midst of it, what can you tell us about how the pandemic has affected you and your institution, both operationally and curatorially?

The pandemic challenged everyone on a personal level and on an institutional level. Certainly for me it has been an adjustment as I assumed the position of director only a few months prior. However, I can say with certainty that the CCA was prepared for some of the immediate consequences of the pandemic.

We were able to smoothly transition to remote working. Transitioning our curatorial work online has been a project of the CCA even before the pandemic. For the CCA, the institution’s online presence is a referred to as a “second building,” an independent, curated entity. The “first building” is the physical building in Montreal, an idea introduced by Mirko years ago, which has been a helpful conceptual framework for the institution. I intended to evolve this notion in January 2020, to move it from two divided but connected buildings to “one CCA.” Meaning: The CCA’s digital output will be integrated into and become another significant way to express the curatorial voice of the institution, rather than simply being a way of communicating and distributing content. This is why new media, video, films, documentaries, the web as an editorial platform, and the use of social media as content platform became fundamental for us. I think the pandemic accelerated this move with no hesitation, with a spirit of experimentation and a willingness to take risks.

If other institutions compete for “foot traffic” or “likes,” I’d like to think we’re better off, as we search for eyes and brains. We’ve always counted on a curious but dispersed global online public, which over the last fifteen years has created possibilities for new encounters with different publics beyond geographical or temporal limitations.

Our strength resides in curatorial formats, but I must admit that we initially struggled as an institution to translate the nuance of our research and its processes done for exhibitions into a digitally coherent entity. The last thing we wanted to do was give virtual tours of our physical space. So a challenge for 2021 is: How, through digital formats, do we more effectively share knowledge, content, and ideas which stoke curiosity and engagement from our publics? If we succeed, I think this will be a good step forward for the CCA, especially in our eventual post-pandemic reality.

Going digital has its limits. The pandemic has brought attention to the inequity of access and opportunities, but also the limits the digital world imposes on conducting research with primary sources. On our side, we tried to support scholars and researchers work by organizing Zoom sessions in our vaults to allow access to our materials, which were then digitized. In the future, digitizing primary sources will increase to support research-at-large and provide greater access to this resource. As a response, this year we are launching a new experimental digital fellowship that considers how we could take down geographical barriers and grant more access to our collection to a diverse set of scholars. Although it was born in these odd circumstances, this will be a long-term program.

At the same time, there has been a renewed movement for racial equity at large in society, but also within the realms of architectural practice, education, and media. This was unfortunately prompted, most recently, by the murder of George Floyd, a Houstonian. Has your institution had conversations about this important topic as it relates to the study of architecture? How might ideas of race and its difficult relationship to architecture and its history be addressed at the CCA? I’m wondering how this might affect not only the exhibitions and programming, but also how the museum collects and archives material from architects in Canada and around the world.

Certainly, the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed around the world have impacted us deeply. The act of collecting, describing, and showing in collections and museums all involve a set of choices that inherently include and exclude histories, which has disproportionately erased, disvalued, and excluded contributions and perspectives from people of color. The weight and implication of these actions, more than ever, are being felt and can no longer be dismissed and ignored. Once viewed as a seemingly basic action, collecting is now rightfully under intense scrutiny.

Together with questions of equity, diversity, transparency, and decision-making I would say the way governance is understood inside this institution has been questioned, and there’s a desire for change. Like many institutions we are doing the work of self-rediscovery and awareness as we reconsider many of the decision-making processes and ask how we could be more open, transparent, and inclusive. CCA is a Canadian institution, and Canada has its own history and ongoing issues with systemic racism and colonization that have not been properly addressed. We should acknowledge the limited effort done up until now to open up the CCA to Black and Indigenous scholars, to diversify material in the collection, and curatorial programming.

In the last years, the CCA has committed to actively expanding its perspective beyond a white, male, and Western framework. This happens through acquisitions and research that embrace stories from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The institution is focused on expanding these areas, engaging with scholars and curators who could bring forward more diverse stories, and introducing its own narrative and complex set of questions in architectural discourse.

However, this work shouldn’t be done in an encyclopedic way, in an attempt to fill all identifiable gaps: the CCA has never imagined the collection as a flat body that covers a universal story. Instead, it has focused on shifts and transitional moments in history and subsequently their related geographies and figures. So, the growth and expansion should follow this core principle. New future inclusions should reflect new modes of operating in accessing materials. The collaborative acquisition of the Álvaro Siza fonds with two Portuguese institutions (the Serralves Foundation and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation), for example, was the best answer in managing the legacy of both a local and global figure in a non-disruptive way. This stokes new questions in how to diversify the collection and how to approach archives or projects without repeating a colonial model of extraction of knowledge and resources from their contexts.

We’re preparing a new project in 2022 that will focus on the circumpolar North. For this project we shifted away from the mono-vocal curatorial approach and are facilitating a team of co-curators; two are Inuit and one is Sámi. This multifaceted approach will deliver a project that critically looks at the colonization of the North and how it has been enabled through architecture and infrastructure-building. But it will also inspire new ways of looking at these territories from within and support forms of Indigenous sovereignty.

What lies ahead for the CCA—and for you—in 2021?

We will continue to investigate the connection between architecture and society by tackling questions about how architecture could better care for society as its needs change.

Our work in 2021 is anchored in a series of initiatives all under the title Catching Up With Life. This hones in on how society is changing in respect to family, love, friendship, work, labor, governance, ownership, debt, consumerism, fertility, death, time, retirement, automation, and digital omnipresence. Surveying this societal shift, we ask and question how architecture and urban design could better understand and support new ways of life. While contemporary values are rapidly reshaping the built environment, architecture should not only be responsive—it should try to anticipate and even influence the direction of society through spatial endeavors. The output for this will be varied: an exhibition, a book, two web issues, a podcast, and a dedicated Instagram account. As I mentioned before, a strong and purposeful digital content will hopefully offer the opportunity for different voices to take part and contribute to advance the thinking on these issues. A part of this research is the trilogy of documentaries, which I mentioned earlier, that focus on current societal changes that present challenges in cities.

We will continue our work on Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture, a collaborative and multi-disciplinary research project on architecture’s complex developments in sub-Saharan Africa after independence. We will also start a new thematic research initiative called The Digital Now: Architecture and Intersectionality. This will focus on how digital design simultaneously intersects and relates with race, class, gender, ableism, and sexuality.

Revisiting cataloguing and how objects within a collection are described is a fundamental way to open-up material to diverse stories and readings. I have always thought that the limit for our collection, which is mainly visual media, is that the search in our databases is still done through words. So, we have begun to seriously ask: How do we describe the current collection in a way to make it both more discoverable and invites more diverse and critical perspectives? Increasing tagging and adding information around the project, such as including information about collaborators for architectural projects when possible, also helps both enrich discourse and potentially reveal unknown actors influencing a project. Certainly, this effort is something we have already started and will be continued for many years.

The CCA is a relatively young institution, but in the last forty years it has become a reference in the field of architecture for its thorough research and convincing ideas in museology, stimulating curatorial voice, the consistent scope of its broad collection—although admittedly it’s predominately composed of a Western, white perspective. It’s imperative for the CCA to be able to continue putting forward compelling curatorial ideas, to inquire within overlooked fields of research, and to continue to grow and diversify the collection to best respond to future investigations and pressing questions.

As for myself, beside contributing to some of the curatorial endeavors, I will continue to learn how to do this job. Curating an institution is a very complex task, especially for a place like the CCA, which is a nimble, curious, and provocative institution. We always want to anticipate what comes next.

Architect, editor, and curator Giovanna Borasi joined the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in 2005, first as Curator of Contemporary Architecture (2005–10), then as Chief Curator (2014–19). She has been the Director of the CCA since January 2020.

Borasi’s work explores alternative ways of practicing and evaluating architecture, considering the impact of contemporary environmental, political and social issues on urbanism and the built environment. She studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, worked as an editor of Lotus International (1998–2005) and Lotus Navigator (2000–4) and was Deputy Editor in Chief of Abitare (2011–13).

One of her latest curatorial projects is a three-part documentary film series that reconsiders architecture’s relationship to and understanding of home and homelessness, living alone, and the elderly. The first film, What It Takes to Make a Home (2019), now available on the CCA’s website, screened internationally at film festivals and institutions, including at the United Nations headquarters as part of the 58th Session of the Commission for Social Development. The series aligns with an institution-wide set of initiatives in 2021–22, collected under the title Catching Up with Life, which explores how architecture and urbanism could better respond, adapt, or anticipate changing notions of family, love, friendship, work, labour, automation, governance, ownership, debt, consumerism, retirement, digital omnipresence, and death.