“Such a limited view was often taken of the Rio Grande throughout its history; for along its great length, and in different times, on different missions, travelers discovered the river in segments, named them differently, found contradictory characteristics in them, and for many generations did not form a comprehensive theory of the river’s continuity, variety, and use.” —Paul Horgan, Great River: The Rio Grande in North American History (1954), 901.

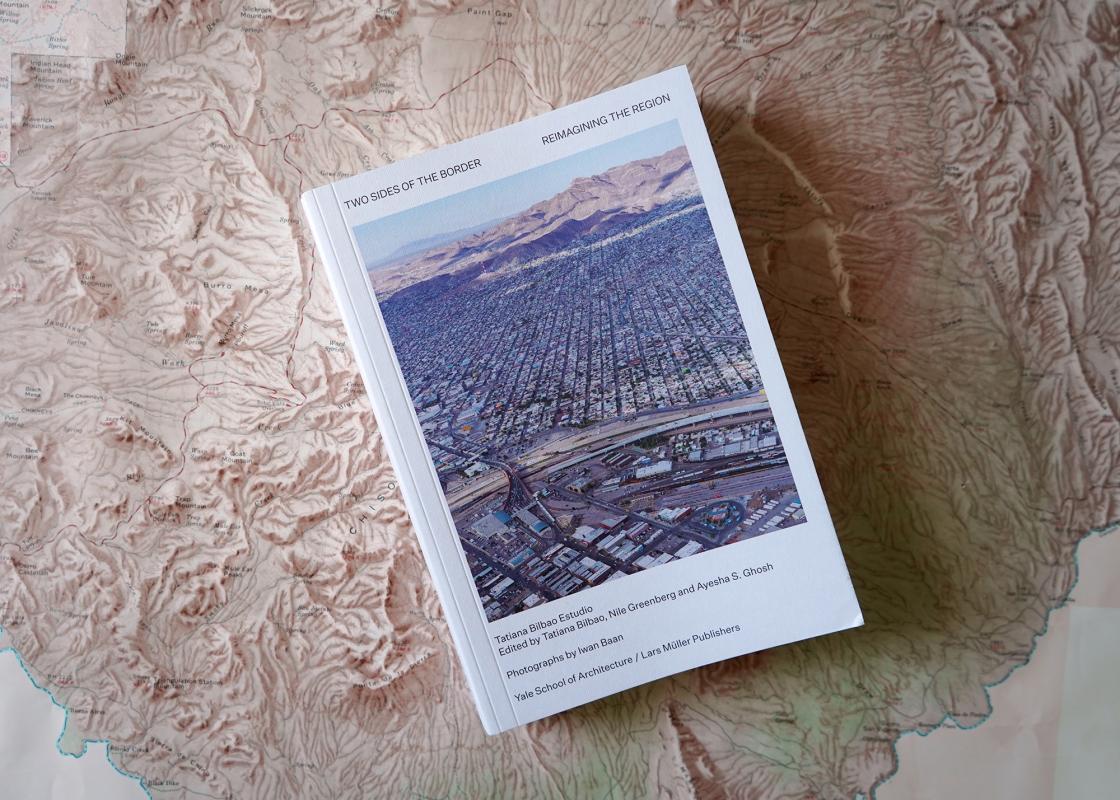

Two Sides of the Border: Reimagining the Region is a collection of essays, speculative projects, and images that describe and reimagine a region shared by the United States and Mexico. Under the direction of Tatiana Bilbao, a Mexican architect, the first iteration of the book was presented as an exhibition at the Yale Architecture Gallery in Fall 2018. It brought together the work of an alliance formed by Bilbao’s 2018 design studio at Yale with thirteen other studios from twelve architecture schools in the US and Mexico. The show later traveled to Fayetteville, Arkansas; Berlin, Germany; and El Paso, Texas.

Bilbao is joined by a host of collaborators. The Dutch photographer Iwan Baan, known for his ability to document architecture as a vital part of contemporary life, photographed the sites investigated by the students’ work. Nile Greenberg, one of the book’s editors alongside Ayesha S. Ghosh, helped curate and design the exhibition, an undertaking he says was influenced by the writings of the Mexican-American novelist Valeria Luiselli, especially The Story of My Teeth, in which she proceeds by “layering multiple narratives on top of one another, each illuminating a particular truth.”

Although Bilbao informs the reader that the book, published last year by Yale School of Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers, doesn’t have a beginning, middle, or end “in the traditional sense,” its index suggests a chronological arrangement of sorts. The stories and their authors are diverse, from Los Angeles landscape architects Terremoto to El Paso-based architects Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller to well-known Mexican artists Pedro Reyes and Carla Fernández. Their sites of inquiry extend from New York to Baja California. Bilbao invites the reader to rethink the border as a single region through an open perspective—a clean slate. Early on, Bilbao writes that “the key moment of the project was opening the process of understanding that these issues happen in Mérida, in San Francisco, or in Ulysses, Arkansas, Chicago, and not only in the hyper confronted El Paso and Ciudad Juárez.”

The book’s essays begin with the left page of the spread devoted to a diagram of the US and Mexico as a single entity. The locations of the essays are placed on the map with a thin dashed line that extends vertically to show their longitudes. While the essays span across countries to deliver histories and current challenges, the diagrams help the reader navigate between cities.

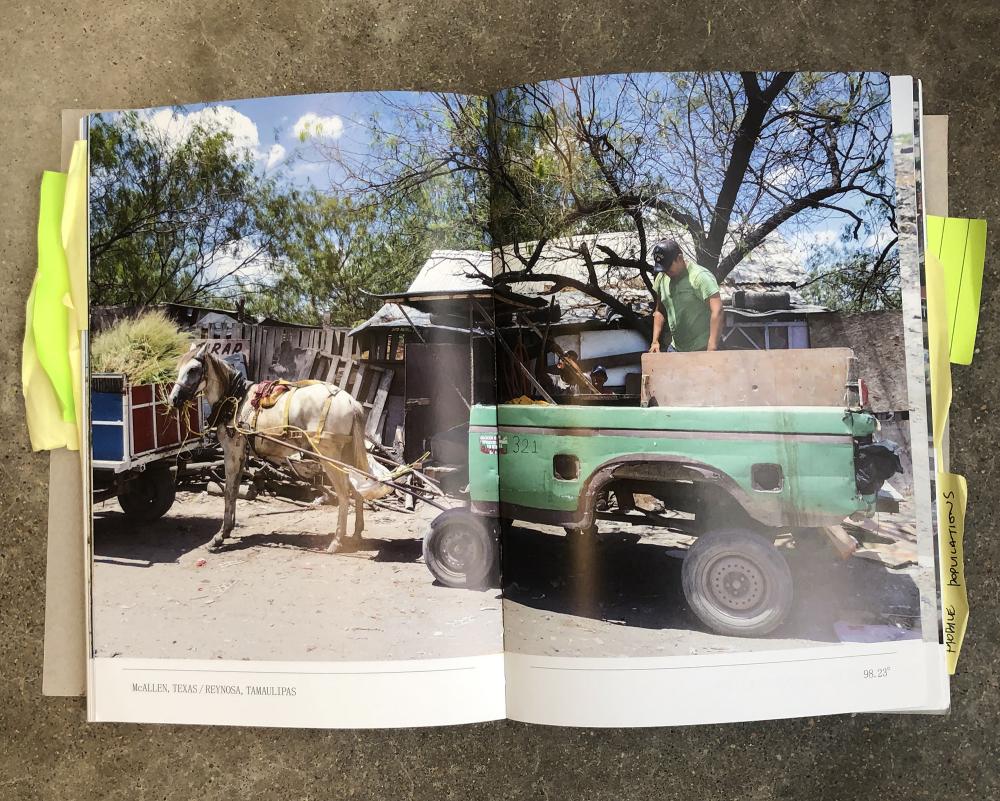

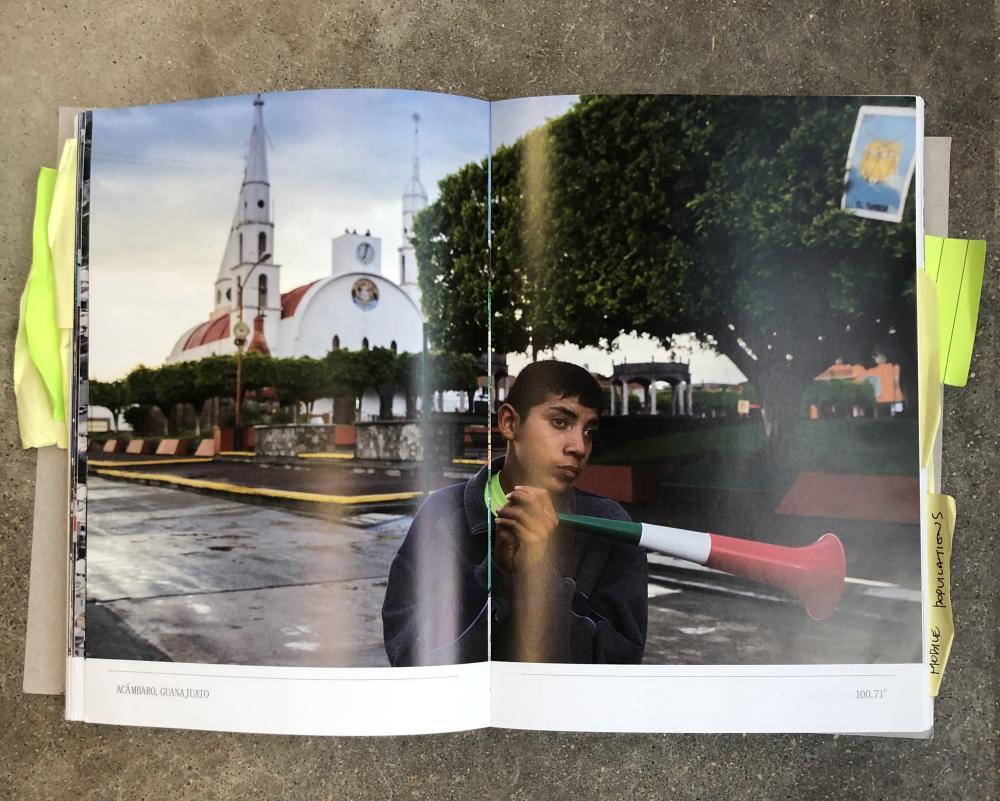

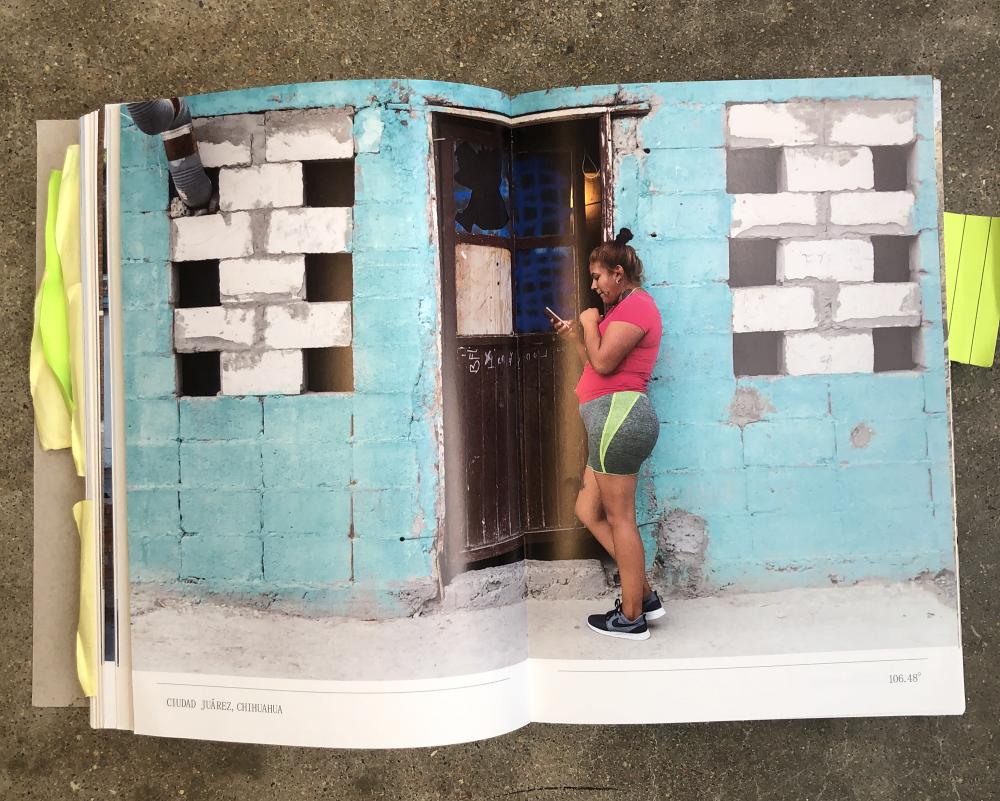

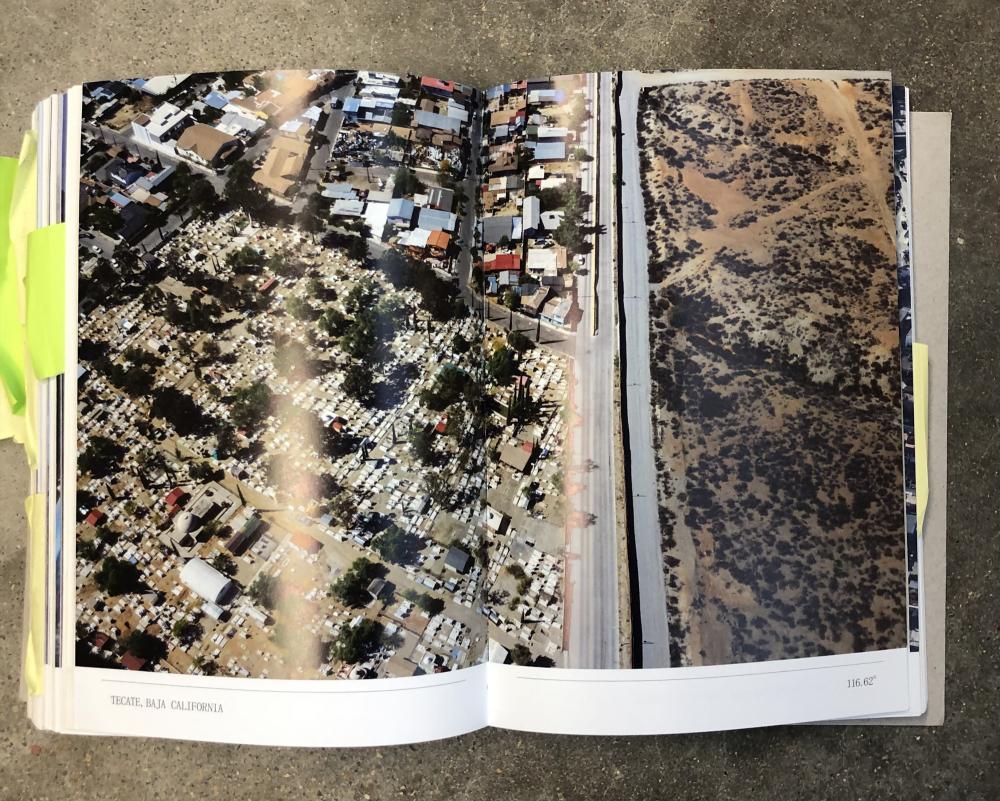

Ultimately, it’s Baan’s full-color images that ground the reader and reveal the human conditions behind the stories. Baan pulls you out of the window seat and takes you on a magic carpet ride, zooming in and out of people’s homes, backyards, streets, and overhead views. He reflects that

seeing the border and the wall prototypes from the air puts it in such perspective, seeing the massive density on the south side of the wall and this little fence that’s trying to hold it back. I think it’s a metaphor for what we are experiencing these days.

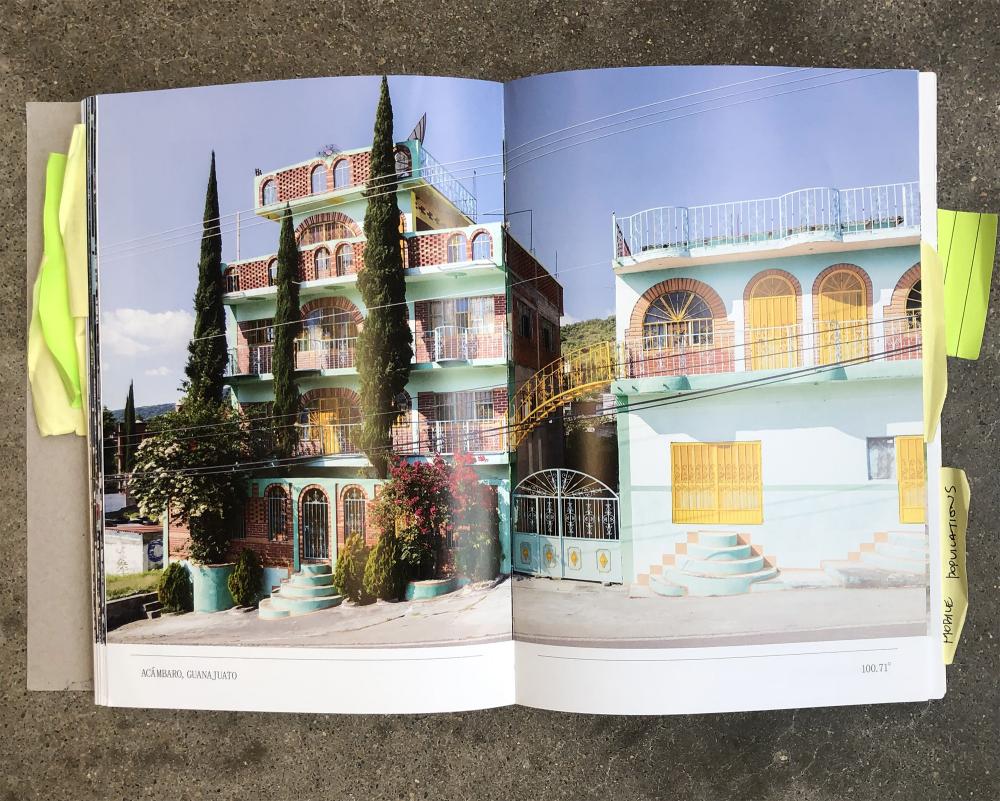

In the spirit of photographer William A. Garnett’s aerial series Lakewood, Baan’s industrial borderland landscapes cut off the horizon. The image’s angle turns inward, with subjects pushed out to the edge of the frame, close enough to touch. Like Garnett, Baan seizes the dichotomy between the “imagined and rejected” in various borderlands by beautifully capturing the desolate rural and empty suburban landscapes. By looking down from an altitude low enough to recognize the vast absence of human activity, one strangely looks back at endless geometric rows of mass-produced homes within large swaths of desolation captured by Garnett in the early 1950s. Similarly, Baan’s photograph of stucco boxes that appear to go on forever in a suburb in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, is a telling example of NAFTA’s effect on the industrial and rural areas of northern Mexico. Baan explains, “you think it is just an economic agreement, but it has a major impact also on the landscape of different places.”

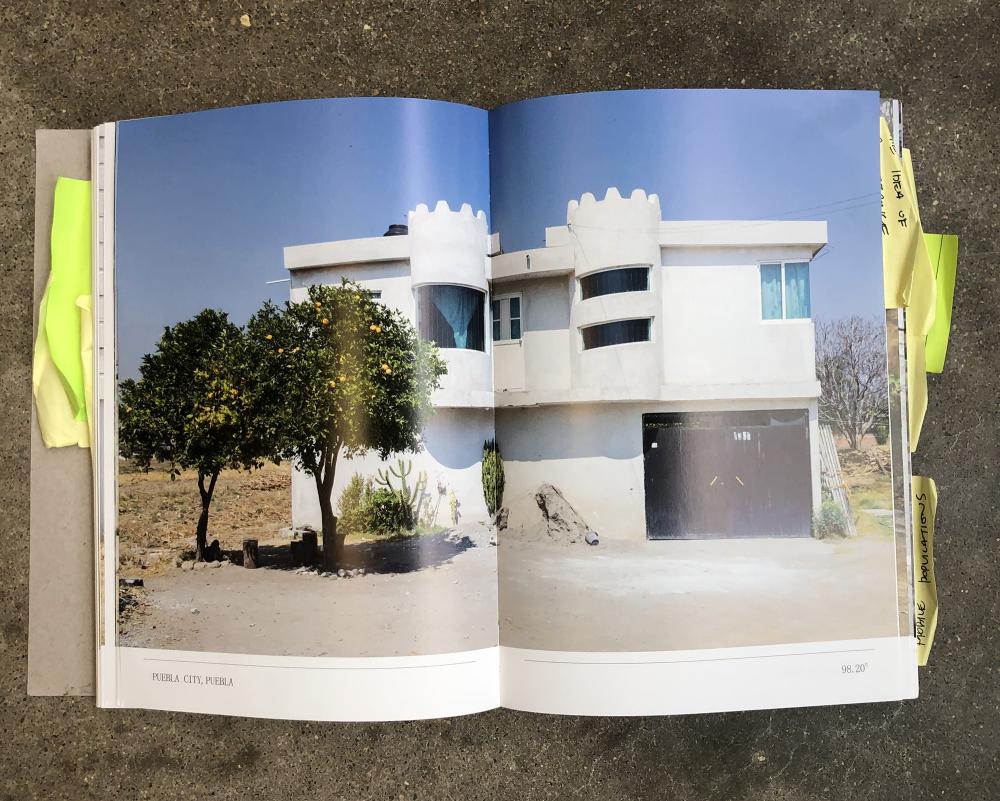

Baan’s images make visible another material effect of NAFTA: remittance houses, a topic explored by Sarah Lynn Lopez in her essay “The Migration of Money, Objects, and Aspirations: A 100-Year-Long Regional History,” which traces the transborder history of “crisscrossing of objects, dollars and aspirations” between the US and Mexico. During the early part of the twentieth century, Lopez explains the wage discrepancy recorded Mexicans earning up to “thirty-six times” more in the US than their Mexican neighbors, and that “these ratios were dramatically higher for rural workers.” Other factors such as the Mexican Revolution, the Cristero War, drought, and new railroads also contributed to immigration, which a 1920s and 1930s study commissioned by the Social Science Research Council termed the “Mexican Problem.” Initially, the migrants would return with purchased goods such as watches and cars. These objects later turned into “Americanized time” and roads funded through remittance dollars. Lopez observes that “remittance homes tend to disrupt small-town fabrics: new houses are pulled back from the continuous façade, second stories emerge, houses are brightly colored and hyper-ornamental.” For her, remittance façades reflect personal experiences conditioned by a mobile life. In the prior photo bank, Baan captures houses in Puebla City, Puebla, “that distinguish themselves from those who never left” by elongated castle-like details and crenellated ornamental parapet roofs.

Although everyday people working and living along the US/Mexico border weren’t the main focus of the book’s essays and student work, Baan devotes about half of his images to capturing a poignant and unfiltered humanity along the border. This thread remains largely neglected in talks with four participating students led by Greenberg and Diego Del Valle on the “internalized nature of architecture.” During Columbia GSAPP student Tonia Sing Chi’s discussion of her project The Manual of Earth Block Architecture, she was asked who she was designing for and how can we think about bridging the gap between academia and communities. Her response underscores the chasm between education and practice in architecture: “‘What is the point of talking about this continuously?’” she asked herself initially. “We aren’t closing that gap or that distance. We’re just talking to ourselves.” Although she considers the discussion critical during a (slow) social shift in her academic training, she also suggests that the solution may be to focus on a process rather than “imposing” values. “In architecture we do that a lot, unfortunately,” she adds. She puts it another way:

I would never produce this manual and distribute it to people in rural Mexico. I would be embarrassed to do so […] I don’t want it to be something that I’ve just come up with, without any of their input.

Sing’s misgivings underscore the distance between academics and the communities they study. How do architects return to seeking an “understanding of society” instead of focusing on, as Bilbao puts it, “individual projects” and the resulting praise for “changing neighborhoods,” an effort that sounds like gentrification? Unfortunately, the critical voices of other students were only included at the end of the book, where the Studio Index is dense and difficult to read. I found myself zooming in with my phone in order to decipher the descriptions of each project.

In his essay “Terra Incogonita,” Andrei Harwell asks: “How did we arrive at this seemingly precise line crossing the country?” He states that even the maps in our “sixth grade classrooms” are powerful sources in visualizing the world the students “belong to.” Harwell emphasizes that “maps, because of their visual accessibility, immediacy, and vividness, played a key role in how we defined, and how we today visualize and understand, our identity as a nation.” He affirms that these maps reinforce boundaries exploited by officials aiming to project hatred and fear of people illegally crossing the southern border. The resulting xenophobic policy establishes an emphasis on division that “must be made more palpable, more visible, more functional—with concrete and steel, with walls—in addition to reinforcing it with soldiers, drones, political policies, and economic measures.” The photos and maps of the border by Thomas Paturet, which follow Harwell’s text, underscore the division’s arbitrariness.

Throughout the book, Baan’s visual record teaches us about a new kind of boundary representation, one that incorporates the variety and transnational cultural realities of this contested and opportunistically politicized topic. Harwell explains that the journals written by Columbus and Cortez were not mappings but first-hand accounts of their observations and the people they encountered. Although mapmaking improved by the end of the Mexican-American War, the “New World made it impossible to mark the ground itself.” Harwell describes the Mexican American treaty as being defined by “little or no direct knowledge of the borderlands” and instead defined by a line drawn on a map by colonizers. Nearly two centuries later, our understanding of the border’s complexities are sadly only slightly more nuanced. Though not a comprehensive theory, Two Sides of the Border is a notable attempt to add detail through the formats of the architecture studio, exhibition, and publication.

Celeste Ponce is Founding Principal of Ponce Architecture and an adjunct professor at the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design.