Jack Murphy (JM): To start, could you speak about the role of the architect in advocating for affordable housing? Why is it important for architects to work on housing today?

Neeraj Bhatia (NB): Market housing more often works on architecture instead of the other way around. The current economics of multi-unit housing and land value limit most architectural agency and perpetuate the inequalities we currently witness in society. Architects in North America are often faced with the difficult question of how to stretch their limited agency and funds to produce something more than the market can offer. They’re always pushing against the market in the current set up. This is why it is so crucial for architects to work on housing—to find alternatives against the logic of the market. These alternatives could offer different notions of value. In doing so, architects can remove housing from existing merely as a speculative act and instead redirect it towards values such as bringing people together and supporting diverse family arrangements and ways of living. How we advocate for that value needs to come from our tools—from designing new typologies to representation to questioning the underlying invisible forces that shape housing. I think that for architects to really have agency in this conversation and to break the loop of being subservient to the market, it might mean more architects taking risks and playing the role of a developer. It might also mean other models of development; for example an architect and community group might join together to self-fund a building, such as the Baugruppen model in Germany. If we believe housing is a right, architects can and should play an important role in structuring new models for housing.

JM: How do you understand the interface between the work of architects, on one side, and on the other, the entities that might commission public housing? In your own work, how have you worked with governmental agencies to explore what architecture can do?

NB: That's a great question. I think architects need to be educated on how buildings relate to each other and the city in a more complex manner than simply formally. This includes interfacing with planning as a discipline as well as development, real estate, etc. Instead of seeing our role as “convincing” others, we should see it as a two-way dialogue and be open to learning through collaboration. Obviously economic value is quantifiable and easy to advocate for, but qualitative values can also be advocated for when people come together in making decisions.

The Urban Works Agency, a research lab I direct at the California College of the Arts (CCA), has worked collaboratively with the San Francisco Planning Department to examine the Bay Area housing crisis on a series of projects since 2014. The Planning Department is well-aware of the housing crisis and is eager to find alternative ways of organizing and designing housing. Policy is the way to change this, but the difficulty with policy is that it's not accessible for most people. This makes it hard to understand the physical ramifications of implementing particular codes, policies, and guidelines. But this is something that architects do very well: We visualize and represent the future. We can take a policy and ask what the city might become with its proliferation, and we understand how forms of representation can act as a tool for advocacy for or against that policy. This is really important, and that's where architecture interfaces with law.

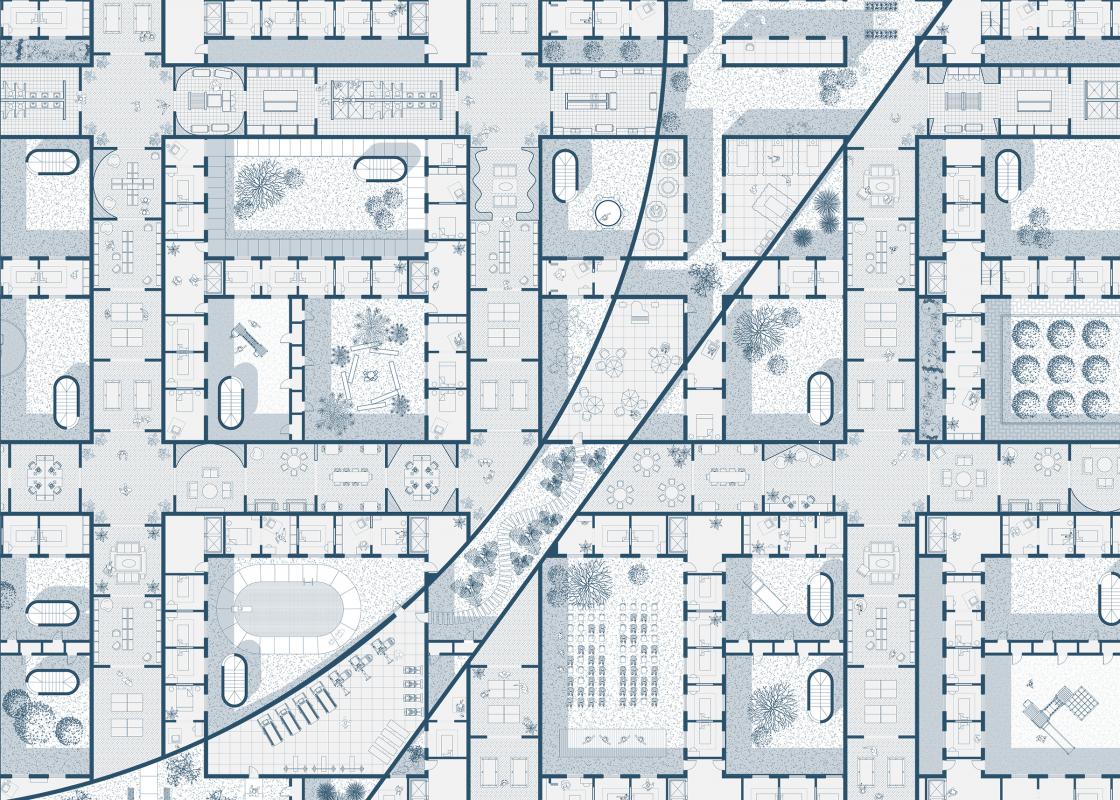

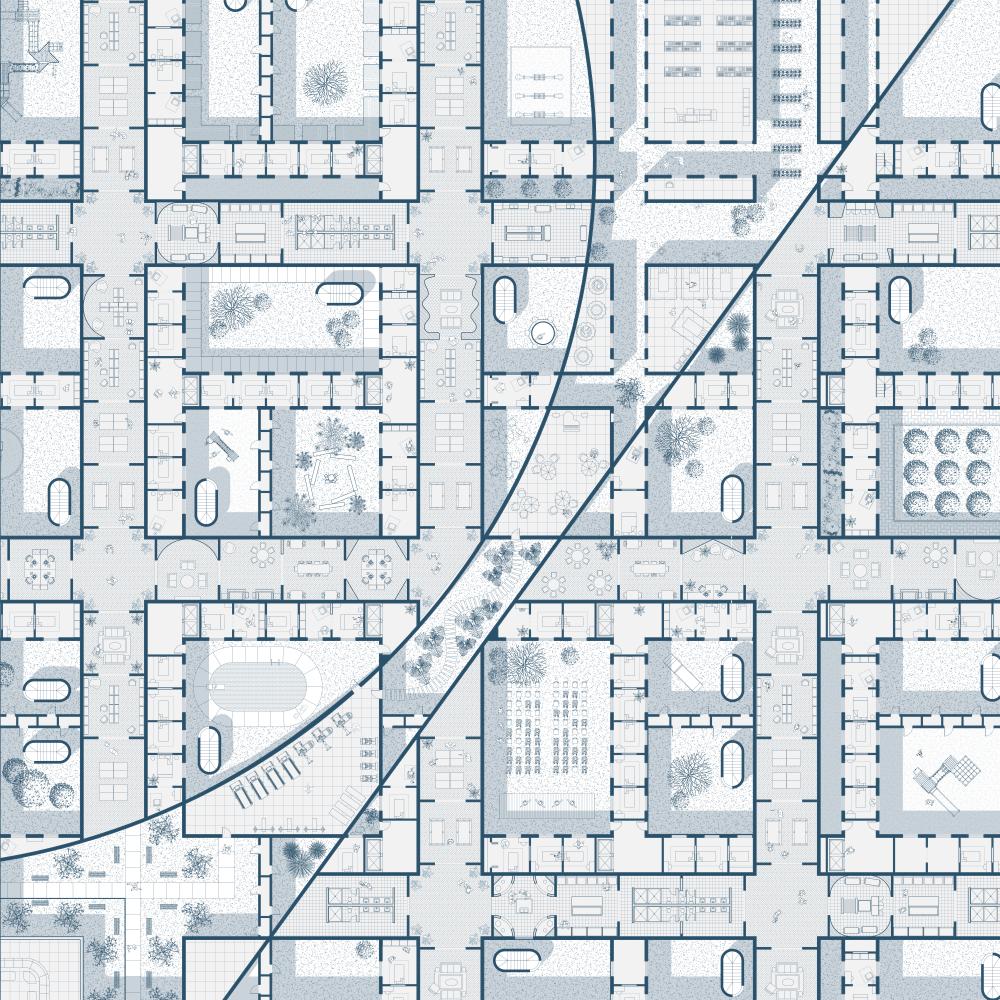

For instance, in 2014-15 we did a project entitled Urbanism From Within, which focused on accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in the city. We were asked to analyze the ramifications of opening up ADU regulations and to de-stigmatize what an in-law unit might be. At that time, there were already an estimated 50,000-75,000 ADUs in the city; they were just illegal. People were living in subpar, unregulated conditions, and these situations were also invisible in a legal sense. In terms of a planning department’s ability to make proactive decisions about how a city should manage itself, that form of density was completely off their radar. By legalizing these dwellings, they could actually respond to this density while improving living conditions. We isolated fourteen housing typologies that make up the primary fabric of San Francisco and did a series of design-research explorations to show how these typologies might be altered to increase density and encourage new forms of sharing. This eventually led to a publication and exhibition whose aim was to communicate how ADUs could be inserted in the city and how the city could more strategically respond to them. Putting this work in the public sphere is the first step to producing a conversation and ideally advocacy, but like all things at the scale of urbanism you also need patience. Behavior and culture are slow things to transform—design here can be a tool to help people become comfortable with new ideas.

I’m also working with my colleague Antje Steinmuller and the San Francisco Planning Department on unpacking different forms of group housing (co-living, communes, hacker hostels, cooperatives, etc.). The Planning Department is getting more and more applications for this type of housing, and it's unclear if this interest is because of the altruism of producing “community” or if this is about creating more density (and profit) within the same building volume—dorms for adults, basically. There's no way for the planning department to decipher these types of things through code alone. Notions of community or governance do not easily translate into planning code.

The Bay Area (and Northern California more generally) has an amazing legacy of communes and co-living experiments that started in the 1960s with various countercultural experiments that ranged from the hippie movement to the Black Panthers. There's arguably just as many co-living projects today as there were in the early 1970s. There’s much to learn from these existing experiments in commoning domestic space—from the space itself to how it is managed, governed, and stewarded. Right now we're analyzing about forty case studies—many in the Bay Area with some international precedents.

We are examining three aspects: hardware, software, and orgware. The hardware refers to the physical architecture—the organization of public/private space, typology, scale, etc. This is where architecture typically operates and where architects are likely most comfortable. The software is the ways of appropriating architecture—from nimble furniture to screen walls, to time-shared spaces. We are also examining how sharing works and the scales of sharing. Meaning, in some of these co-living projects everything shared might be in a centralized commons and there is a strict line between the privacy of your bed/ room to the commons, whereas other case studies have tiered forms of sharing where it might be that three people share a bathroom, seven people share a kitchen, and twenty people share the living room. The last part of the analysis, the orgware, concerns the governance and politics of the project. This is a critical aspect and one of the primary reasons these projects emerge—so residents can have more agency over the way they live. This is also one of the most fragile aspects of a project, and often leads to the demise of a community. This part of our study examines the political system of governance, how labor (domestic, reproductive, immaterial, material, etc.) is organized, how conflicts are addressed, and how stewardship works. Our interest in this project is understanding from empirical research how politics and form might support each other.

Going back to planning, part is the research is translating how these arrangements work into quantitative data—what is the ratio between private and shared areas? How much space does each person have? What types of amenities are shared and at what scale? By extracting data from communes that have found ways to manage the commons and support alternative lifestyles, we can reflect on how design guidelines and codes might follow. This is much more complex than the current definition of Group Housing which revolves around the number of stove ranges in a unit. We are obviously much more than numbers, and the aim of the research is to span from the political/organizational framework to the reality on the ground.

JM: I want to talk about teaching collective housing in the architecture studio. Historically, housing has been one of the main building types that architects have produced, and while its realization is rare today, it's also having a conceptual resurgence. Many schools offer studios that invite this kind of speculation. Troy Schaum here at Rice Architecture has been teaching a co-living studio as part of his Totalization course for a while. I know you and your colleagues have taught using this prompt at CCA. How has teaching with this project type in mind changed it for you? Have you seen students learning and growing in response to the prompt? How are their imaginations changing about what housing can be?

NB: When I started teaching, I taught design studios that were at the primarily at the scale of the territory and infrastructure, even as a Wortham Fellow at Rice. This was partly because of context: A lot of the studios I was leading in Canada before coming to Rice looked at infrastructure in remote territories. This made sense because Canada is a country defined by infrastructure, much like Houston which is, arguably, a city defined by infrastructure. When I was at Rice, I studied the oil industry and its associated logistical infrastructure, and this work was published as an Architecture at Rice book as The Petropolis of Tomorrow.

I didn't actually teach housing until about 2014, when I was teaching at CCA. One of the primary urban issues in San Francisco is access to affordable housing. San Francisco is emblematic of the late capitalist city—tremendous wealth pushed up against extreme poverty and homelessness. When I moved to San Francisco, I struggled to find housing options that would not put me into precarity, and this is something many of my students also confront. Many of them are living with numerous roommates already in some form of co-living; others might be in micro units. Our studio was set up as a critique of the micro unit, and more generally of holding onto the atomization of housing. What does a kitchen mean if it's just a hot plate and a microwave? What does the dining room mean when it only accommodates 1-2 people? At that point, should we give up the atomization of the unit to get something of higher quality? This trade off—privacy for higher quality and scale of amenities—is something we term “luxury without economic burden.” Students respond to these types of questions because these ideas connect with their lived experience and struggles. This goes beyond merely answering a design prompt to investing in how your discipline might engage issues larger than the building itself and offer alternatives.

One of the most eye-opening moments in the studio for many students happens when we visit a series of communes. As depicted in media, many of these projects are seen as failures because they can't sustain themselves. But the flip side of that conversation is that the difficulty of sustaining the commons is purposeful—this is also the reason why residents have large amounts of agency on defining (and re-defining) how they live. It's not that different than a protest for example. Protests are forms of action that offer vast amounts of agency, but they require the investment of emotional and physical labor to be sustained. Similar investments take place in communes, so it's exciting to visit co-living projects that have existed for long enough that the communities have evolved workable governing mechanisms.

In teaching housing, you unearth the biases that come from the domestic environment that one grew up in—whether it's reactionary or to affirm that form of living through design. As architects we unconsciously absorb a lot from our context and then perpetuate those conditions. I love teaching housing because it exposes students to a range of living conditions as a way to expand the ways of living that we bring into design. While these communes might at first seem foreign to many students, we are continuously reminded that private property and the forms of market-driving housing that we build today are a small part of an otherwise extensive history of housing that was primarily collective.

JM: That's a nice point. If you support collectivity today, you might be characterized as some far left person, but sharing is historically part of city life. There’s a deep history there, but because we've been marinated in ninety years of single-family housing policy in the United States, collectivity has somehow become a radical thing to aspire to.

NB: The idea of the home as a financial instrument changes the notion of the house itself. It's not about your particular lifestyle and who you are, and it's not something you pass to your kids. The home is now positioned as a speculative investment. This privatization of land and housing has brought tremendous wealth—primarily to the boomer generation. We live in a challenging moment right now because access to mortgages is finally more universally accessible than it ever has been. So when you think about minorities who have historically been excluded from this process, now they're now able to get into the game—but at the same time, we know the game needs to change, that the rules of the game are flawed, and that the game can only go on so long. How do you shift the rules now, when those who were excluded from the game can finally play and reap its benefits?

Because housing is tied to land and the urbanization of land, it is currently too unsustainable to keep it as a speculative part of our economy. Private property and collectivity are not irreconcilable, but we have not invested enough energy into designing other models of housing development—this is a critical area of inquiry for architects. In the bigger picture, I do think we need to devalue housing as a speculative act. Decoupling land from economics might not only create more equitable access to housing, it will likely also produce more novel forms of living that are more sustainably managed on the land.

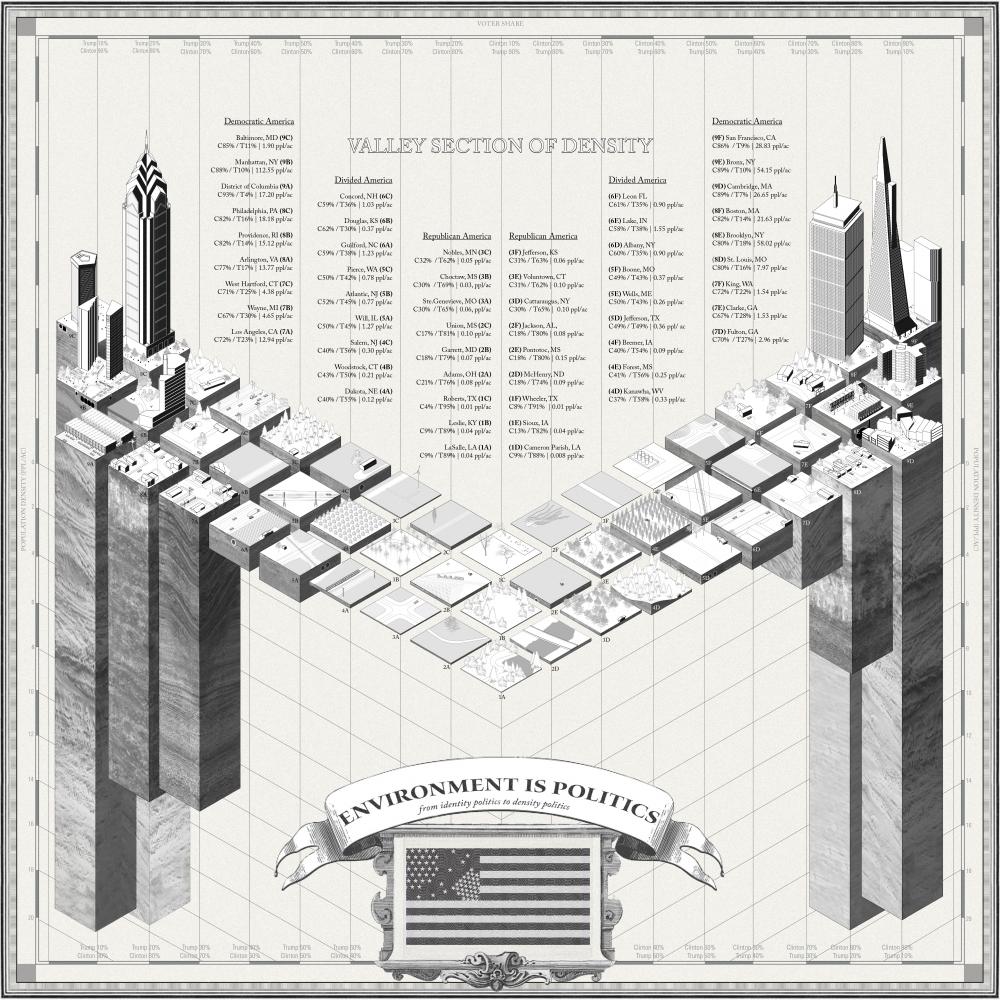

JM: I wanted to ask about the Environment as Politics drawings that The Open Workshop did after the 2016 election and the connection to density that emerged. These drawings and an accompanying essay were published in Places. How do you reflect on this work a few years after completing it, given all of the cruel policies perpetuated by the Trump administration?

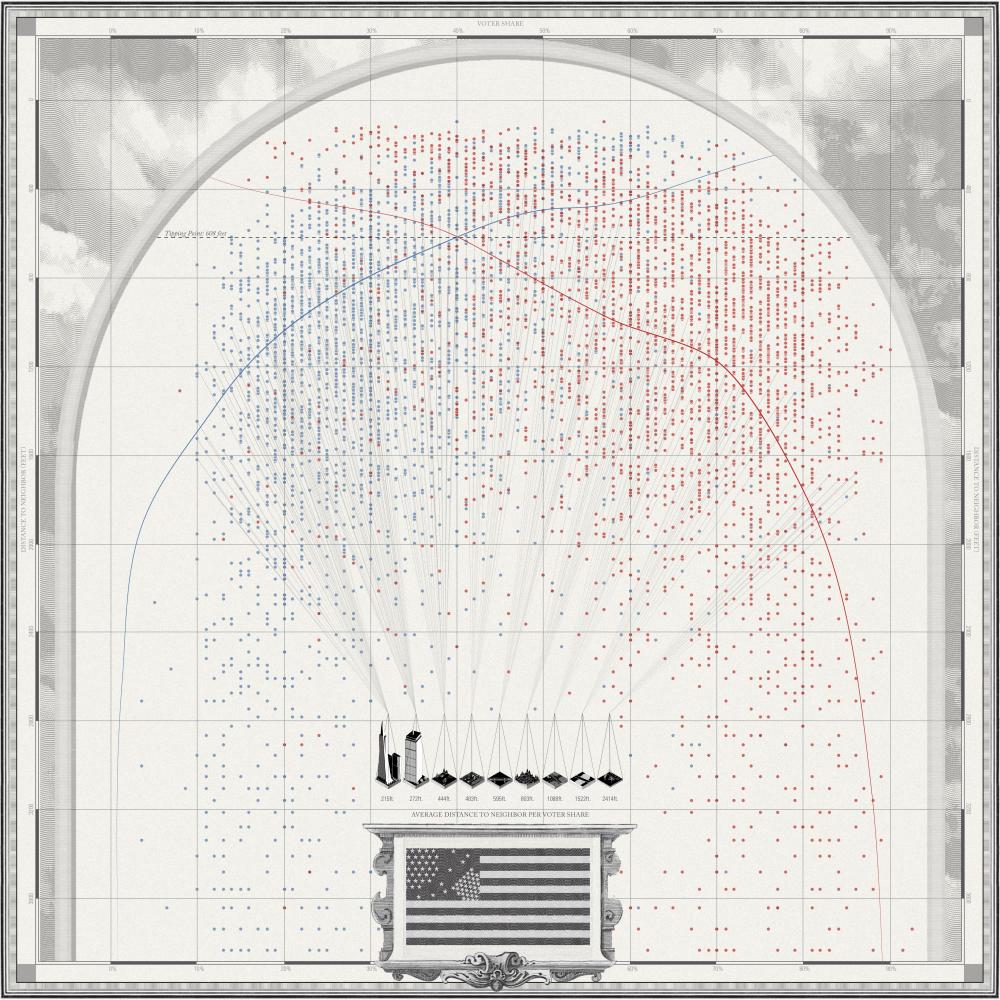

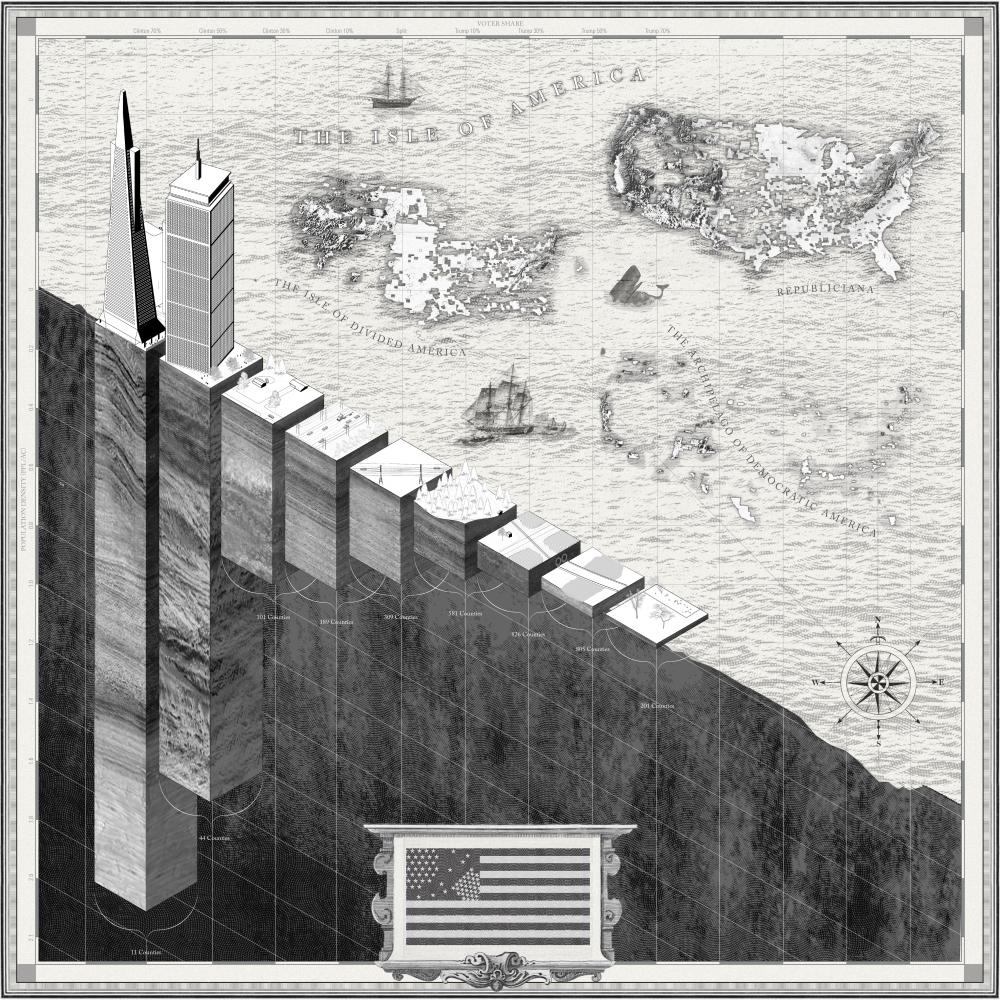

NB: After the 2016 election, many of us in the office were looking for answers. This is a common response when something that is surprising and shocking catches you off guard. At first when Trump won, the majority of maps focused on the state-scaled electoral college maps. These maps were misleading because they implied Trump won by a landslide because of the amount of land represented in red. Of course land does not vote, and America is not just red and blue—in fact it is much more purple. About a month or two later, the New York Times released a more sophisticated county-level map that showed the true complexity of what was transpiring. Soon thereafter, GIS files were released, which allowed us to look in more detail at the numbers and patterns.

As designers and urbanists, you can’t help but look at those county-level maps and see the range of purples and their potential connection to density. While there was much written about the countryside versus city, there was little to no deeper investigations into how much density and living environments play in how we vote. When we think about urbanism today, urban and rural are ends of a spectrum; most of us live somewhere along that gradient. So the question was simple: How much does environment play a role in our politics?

Once we started, we got into things I'd never done before through GIS. For example, we consulted statistics experts to help us work through how to normalize data and how to compare it. It was a revelation because we wanted to make an analysis of how people voted and then compare this to the spaces that people lived in: What did these spaces look like? How were they organized? How close was your neighbor?

When you hear the term suburb, everyone thinks of something slightly different. Between the opposites of city and countryside, we might encounter suburbs, exurbs, peripheral towns, the hinterland, etc. We still do not have the terminology for this range of spaces that exists, nor do we know exactly how they operate in terms of density. We focused on fifty emblematic counties of various ranges of vote share, from 90% Trump to 90% Clinton. We then isolated a one-acre swatch that was indicative of the larger county. This exercise helped us visualize the relationship between voting affiliation and space. What came of this was how clear the relationship between density and political affiliation was—from hundreds of people per acre to less than one.

Looking back on it, it was eye-opening because at the time so much of the analysis after the election was about the impact of social media and identity politics. And, strangely, space was a highly predictable indicator of how people voted. It legitimized the belief that space is much more political than we might think it is. Of course, these densities and spaces are tied to particular forms of labor, lifestyle and culture, but America is less about blue and red states than it is about different instances of density. I imagine that density played a similar role in this recent election. These patterns are also occurring in places like Canada and the UK. Who we are is largely determined by where we are. It’s just that the where might not be a place as we traditionally understand it, but rather where we are on the density spectrum. JM: I feel like the drawings your office made were one of the few clear things that allowed me to understand the previous election. It made very legible something that we know in a deep way but that's hard to articulate. We have so much work to do on the intersection of space and race, though conversation about the racial history of cities has been growing, even in architecture schools. I'm thinking of Richard Rothstein's The Color of Law about redlining, among other books. When Trump dogwhistled that “they're coming for your suburbs,” it's clear there are profound spatial implications and histories lodged in his divisive policies.

NB: Identity politics is surely a large factor in how people vote, and this was a something that came up in doing our research on the 2016 election. Did dense areas produce the “liberal subject” or were liberal-minded people more likely to relocate to denser areas? It’s likely a combination of the two—space conditions us and we in turn evolve our spaces. Trump’s use of the word suburbs stands in for white middle to upper-class Americans, and the they is minorities. Within his fear-driven politics, a form of density and living is really a stand in for a race and class of a particular subject.

To connect this thought back to topic of housing, it's important to know that what we look at and what we choose to value as a discipline carries meaning. In an architecture school, the conversation is curated by professors and outside lecturers. Students need to experience a more diverse series of conversations, and this will only occur if we reckon with race and class issues in the discipline.

This also plays a role in the projects produced within a school—how we judge a design at the end of a semester can no longer just be the physical (often aesthetic) design of the building or its associated representations. We need a more holistic and multifaceted way to unpack and judge the series of decisions that go into producing a work. In housing, we should be thinking about (among other things) questions of policy and the invisible structures that prepares the land for form—and then the relationship of form and people back to that land. Until we increase the complexity of our conversation and who is at the table, we will perpetuate issues that Trump tapped into. Within The Open Workshop, we've never distinguished between form, our politics, and our interests in how people live. These questions are always working with each other. It would be artificial for us to focus on one over the other.

JM: To close, I want to ask about two projects that mark opposite ends of the spectrum between the territory and the house. One is the Commoning Domestic Space for the Venice Architecture Biennale, now in 2021, whose theme is “How will we live together?” The other, the Roosevelt house, is a building, which is exciting. Both of these efforts concern housing. What's at stake in each of those projects?

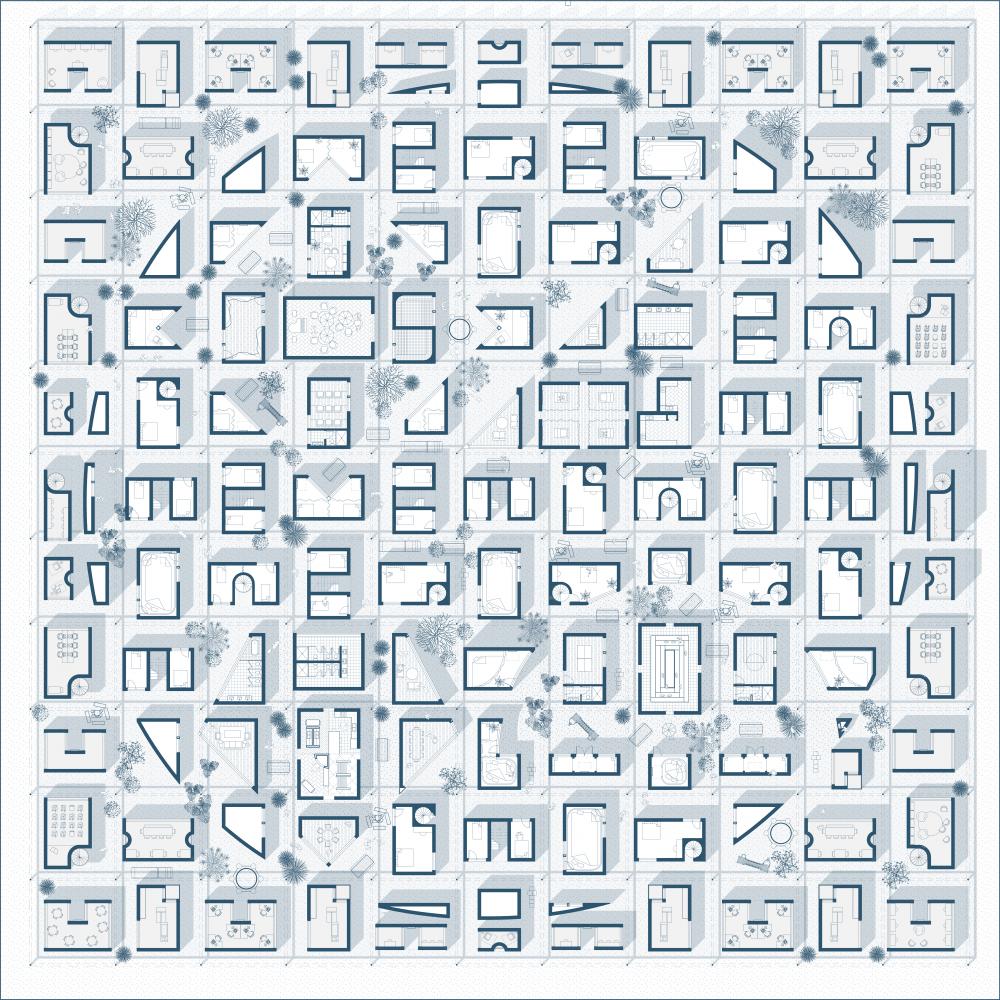

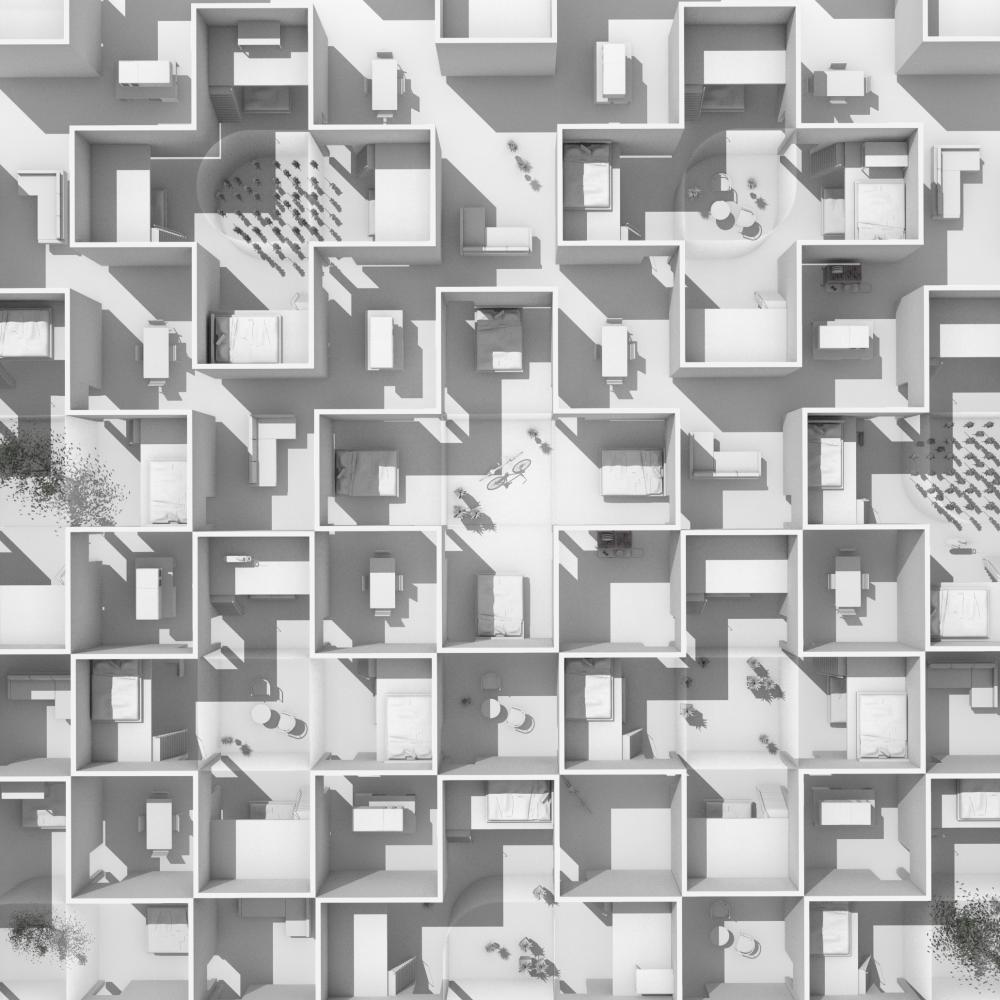

NB: Commoning Domestic Space is a project linked to the research on communes I discussed earlier. The other half of that project is taking the step of translating this research into design. We are currently developing five housing projects for the Biennale. While they could all be built, their intention is to be more exploratory. Each project offers a different relationship between the public and private realm, from one project where there's a strict division between these two conditions to one in which everything is temporal and these realms are constantly being negotiated. If we understand politics as the negotiation between the individual and collective, a similar negotiation plays out in the commune. How do different delineations of publicness and privateness offer different forms of agency to the residents? While the questions asked here might seem broad, they are answered through material and dimensional specificity.

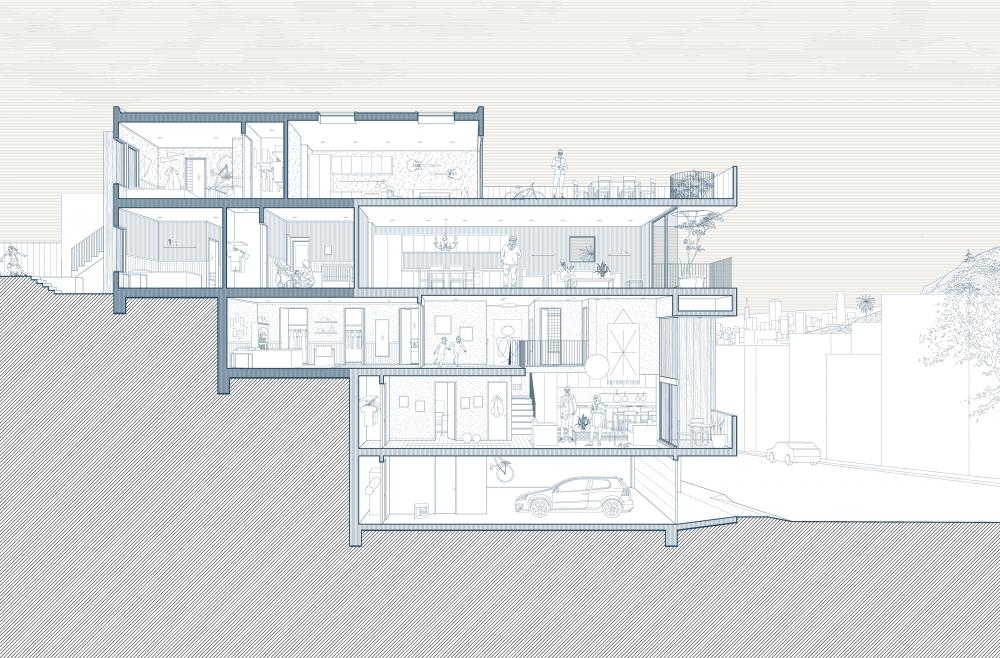

The Roosevelt House is a real world building project that works within the economics of San Francisco while trying to question these logics. It takes a single-family house and reconceives it as a small apartment building. This offers increased density and affordability to the city but also enables varied unit types and demographics. The house has three units at different scales. There’s a two-bedroom, two-story townhouse unit closer to the street, a three-bedroom unit with a large backyard, and a modest one-bedroom rooftop unit. Now this building that originally only contained one way of living offers a degree of the variation that we see in people’s actual lifestyles. This project took lessons from our Urbanism from Within research. We’re adding density to the same footprint while reconsidering notions of sharing. If you imagine other parcels and buildings following a similar logic, all of a sudden you have a more varied, denser, and affordable city. This is how we come full circle back the relationship between architecture and urbanism. We firmly believe that architecture has agency to affect urbanism even at the scale of the individual parcel.

Neeraj Bhatia is a licensed architect and urban designer whose work resides at the intersection of politics, infrastructure, and urbanism. He is an Associate Professor at the California College of the Arts where he also Directs the urbanism research lab, the Urban Works Agency. Bhatia has also held teaching positions at UC Berkeley (as the visiting Esherick Professor), UT Arlington (as the visiting Ralph Hawkins Professor), Cornell University, Rice University, and the University of Toronto.

Bhatia is founder of The Open Workshop, a transcalar design-research office examining the negotiation between architecture and its territorial environment. Select distinctions include the Architectural League Young Architects Prize, Emerging Leaders Award from Design Intelligence, and the Canadian Prix de Rome. He is co-editor of books Bracket [Takes Action], The Petropolis of Tomorrow, Bracket [Goes Soft], Arium: Weather + Architecture, and co-author of Pamphlet Architecture 30: Coupling—Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism and New Investigations in Collective Form. Neeraj has a Masters of Architecture and Urbanism from MIT and a Bachelor of Environmental Studies and Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Waterloo.