In Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning (MAaC), Daniel A. Barber provides a historical account of past attempts to thermally condition buildings before the use of mechanical systems became nearly ubiquitous. His stated hope for the effect of the book is that “by rescripting the historical narrative of architectural modernism, other futures will be seen to be possible.” While many of the names mentioned in his research are familiar, Barber’s unique telling of the past reveals how lines of thinking that have laid dormant for decades may provide solutions to the issues that designers face today.

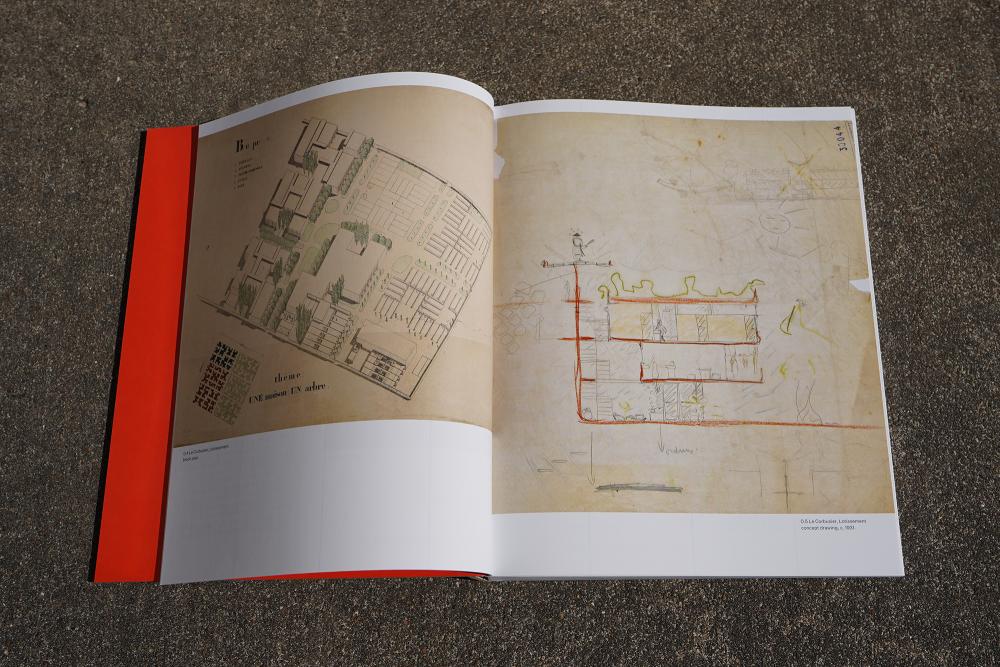

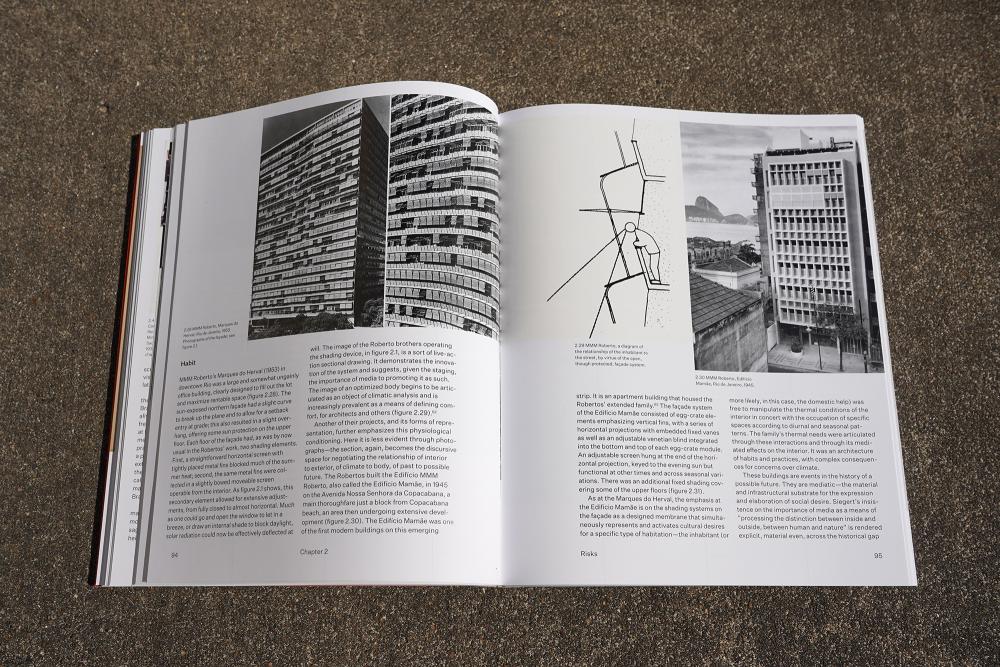

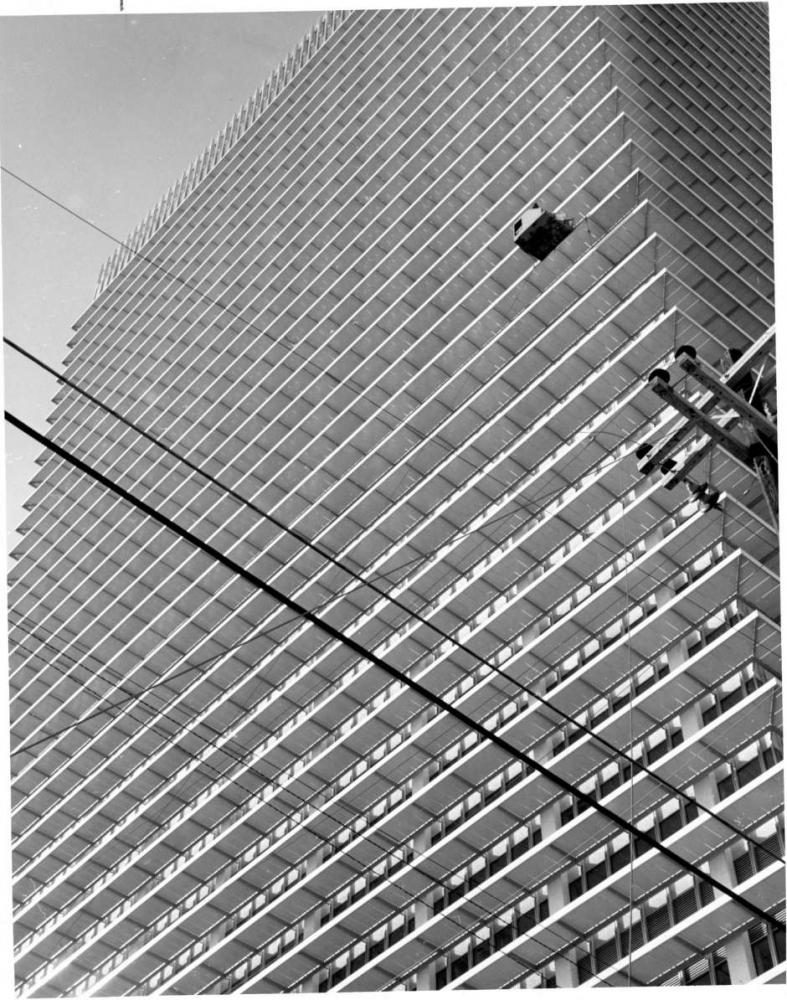

Part I of the book outlines early attempts to produce a climatically responsive modern architecture that creates thermal comfort. Barber draws attention to the role that climatic response played in the work of Le Corbusier while also crediting numerous Brazilian architects with the design of climatically responsive facades developed in parallel to Le Corbusier’s work. Barber dispells the notion that the Brazilians were reliant upon Le Corbusier for their design solutions, one of numerous moments where MAaC seeks to correct historical misconceptions and give credit where it is due.

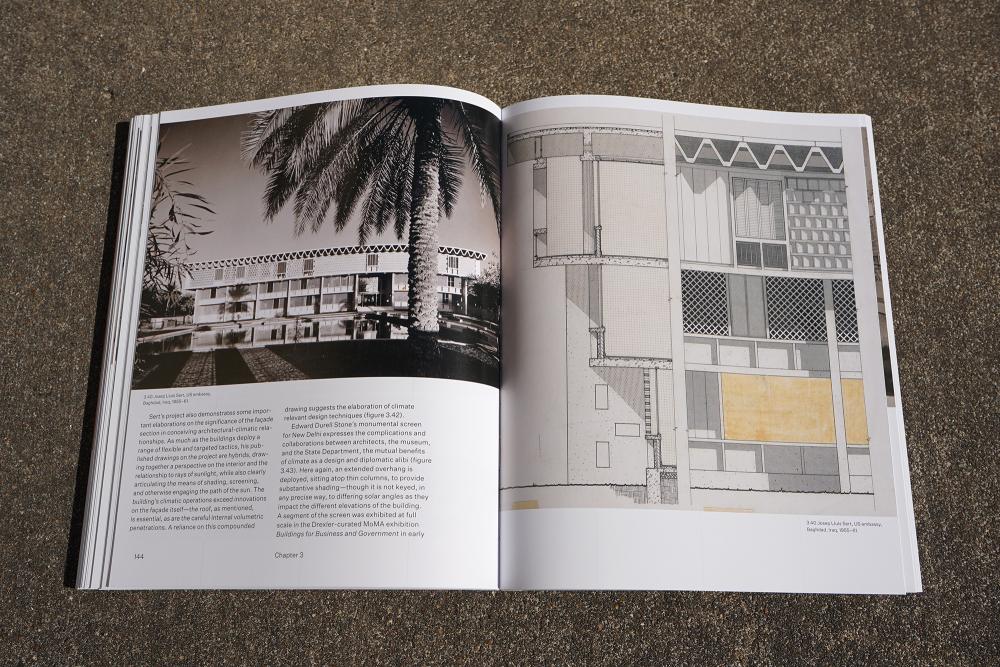

Part I concludes with a chapter on the efforts of American architects to design climatic and culturally sensitive buildings in foreign lands. It opens with Richard Neutra’s socially responsible designs for Puerto Rico and closes with a discussion of modern designs for United States embassies and diplomatic buildings. While many of these designs served to mask more nefarious things than the sun, Josep Luis Sert’s projects in Baghdad stand out as a sensitive and innovative exception.

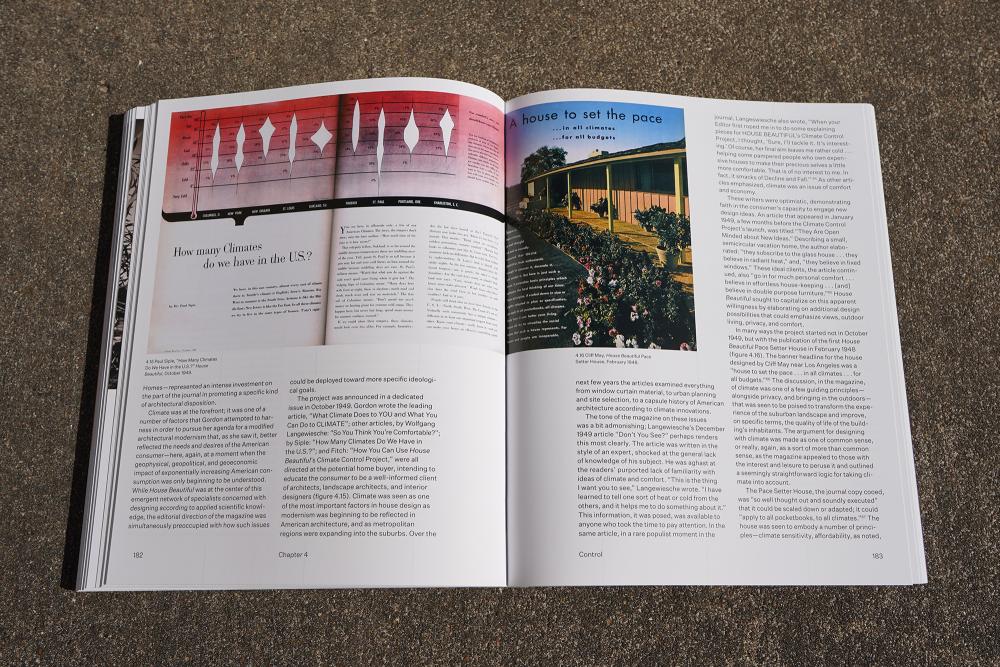

Part II begins with Barber acknowledging that while the previously discussed attempts to provide thermal comfort were more aspirational than effective, continued efforts provided developments that were more rooted in science than in speculation. Of particular interest here is the influential role played by House Beautiful editor Elizabeth Gordon, whose collaborative projects with the American Institute of Architects emphasized that homeowners focus on the principles of regional climatic responses over stylistic elements. Unfortunately, the lack of stylistic concern only extended so far, as the publication took a xenophobic turn in which European modernists were decried as presenting “a threat of cultural dictatorship.”

Barber praises Victor and Aladar Olgay as unsung heroes who were foundational to today’s understanding of the relationship between architecture and climate. Barber documents how their research transcended the aspirational limits of prior architects as well as how their production of technical images served to demystify the complexity of thermal comfort. The championing of these brothers as this history’s protagonists turns disheartening as Barber describes how their work’s relevance dissipated just as it had begun to take form. Barber describes how a variety of factors all contributed to a paradigm shift away from architectural responses toward mechanical solutions to the problem of thermal comfort.

In Barber’s final chapter, titled “The Planetary Interior,” he again asserts the potential for designers to re-evaluate the work of past architects through the lens of the environment and advocates for current practicing architects to pick up these threads anew in order to address pressing issues of climate change and energy consumption. While he speaks to the urgency of the situation, he doesn’t offer possible solutions.

Each chapter closes with a brief conclusion that connects the historical content to contemporary architectural and societal issues. The brevity of these conclusions seems like a missed opportunity to help build a more substantial bridge from the historical examples toward these possible futures. Instead of furthering these discussions, Barber seems content for the book to exist as, in his own terms, “an account of a historical process.”

Barber’s thorough account, written in the distanced expert voice of a historian, shines when it dispels established beliefs. He frequently recognizes moments where racial and gender biases of previous generations led to historical misconceptions, many of which are perpetuated to this day. At other moments, he steers the text away from issues directly related to architecture and climate and instead digresses into historical and political accounts that seem less relevant to today’s readers.

While Barber is a skilled historian, his writing elsewhere illustrates that as an author he can provide more than “just” a view into the past. His essay “After Comfort” in Log 47 reads like a call to action for the profession of architecture. This fact makes it difficult not to consider how this book would read differently if Barber had approached the subject from a more expansive perspective.

There are moments in the book where Barber seems primed to address the cultural value of these climatic responses, but it doesn’t quite happen. As a counterexample, Lisa Heschong’s Thermal Delight in Architecture, published in 1979, also addresses the question of how non-mechanical methods provide thermal comfort, but she explicitly does so “not with the eye of a historian […] but with the eye of a designer.” In doing so, her narrative embraces more humanistic questions of perception, meaning, culture, and experiential qualities that are absent in MAaC.

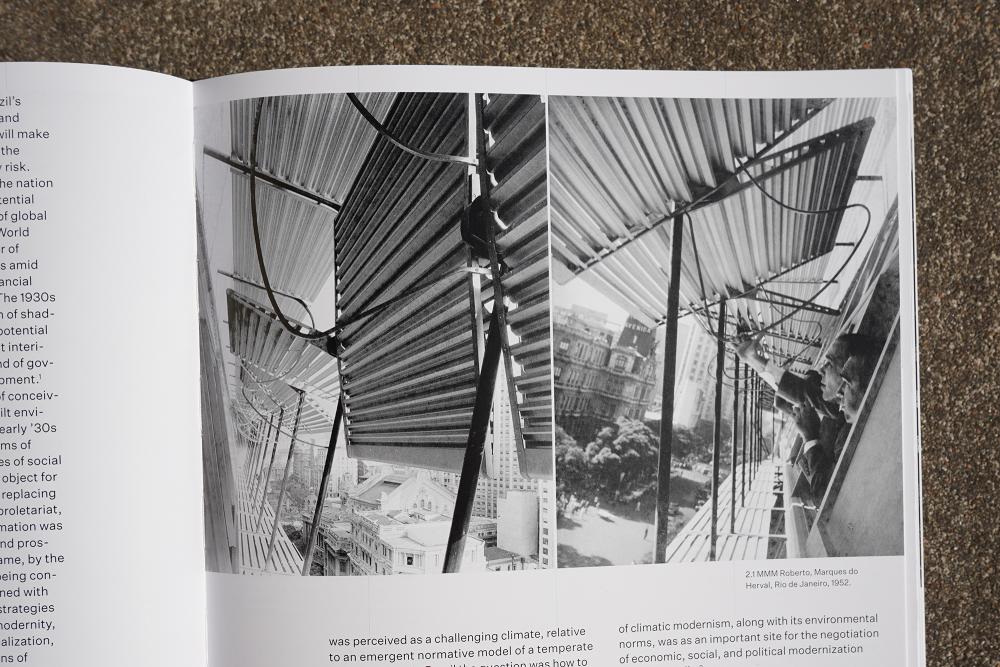

Throughout, Barber’s story is one of the various media utilized by designers to visually communicate concepts, ideas, and values. Barber even extends the definition of media to include the façade of the building itself. Questions of representation and the use of the technical image are present in each chapter, and the book dedicates a generous amount of space to large-scale reproductions of the images discussed. Full-page spreads display sketches, construction documents, and conceptual diagrams, tracking the development of these technical images as they increase in both complexity and clarity. This treatment is no surprise, as the design of this book was handled by Luke Bulman, a Rice Architecture alum and talented book designer.

Barber explains how these images sought to communicate complex ideas in a clear manner. Paul Siple, one of the characters in MAaC, stated that the goal was to produce diagrams so clear “that texts will not be necessary,” an ambitious undertaking given how much information is communicated in these drawings and the ambiguity of their usage in the act of designing. The designers relied heavily on the use of these images, in some cases even eschewing the use of photographs of built work in publications in order to prioritize a focus on the inherent principles over the finished product. The included images offer a fascinating look into the past, but again limit Barber’s scope to be that of the technical image.

It’s interesting to consider how the lessons contained within these images could be re-applied to architectural design in the city of Houston; some mid-century buildings here include strategies shown in Barber’s book, notably the currently vacant ExxonMobil Building, completed in 1963. Shading devices alone won’t suffice to offset the region’s humidity, but reducing the sun’s impact—and expanding the notion of thermal comfort—would reduce our reliance on mechanical systems. One of the remarkable things about the buildings studied in MAaC is the amount of space dedicated to providing shade: The building envelopes are thick instead of thin. While local designers certainly value climatic design responses, the issue may lie more in convincing clients and developers to sacrifice occupiable square feet in favor of ecological solutions. Today’s shift in cultural values may provide a window of opportunity for architects to advocate for such a change, as the desire for the thermal comfort of the interior becomes matched by an increasing need for ethical comfort related to the natural environment.

Throughout MAaC, Barber identifies the notion of comfort as the culprit for our current ecological crisis and suggests that the information embodied in the technical images of the past may offer a possible solution. While his unique perspective reveals a new understanding of that history, his focus is narrow. The decisions we make as designers and as a society reflect our values, and those values extend beyond the technical to include the cultural and the moral. While the book does an excellent job of documenting the subjects it covers, a broader perspective into that past may have provided a clearer vision that could point towards possible futures.

Ross Wienert practices at CONTENT Architecture and teaches in both the architecture and interior architecture programs at the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design.