After the 2020 election and the January 6 attack on the Capitol, a primary message is the power of the media to manipulate knowledge. Media, in some sense, transmits knowledge but doesn’t contain it, and so the qualities of this transmission are of critical importance. Architects know this all too well, as they constantly make decisions about the best ways to situate work, produce images, and navigate the complex terrain that spans between the proposal of architecture and its realization.

One of the outfits to work between architecture and the media most successfully is Ant Farm. The group—Chip Lord, Doug Michels, and Curtis Schreier—have a strong history in Houston, as Lord and Michels taught at the University of Houston. Allen Teleport 2000, an updated version of a media room designed by Michels in 1978, remains hidden within the school’s building. Michels passed away in 2003; the University of Houston maintains his archive. Ant Farm’s presence in Houston was perhaps best captured locally in Tom Diehl’s “Ant Farm in Houston: 1969-1972,” published in Cite 31 in 1994.

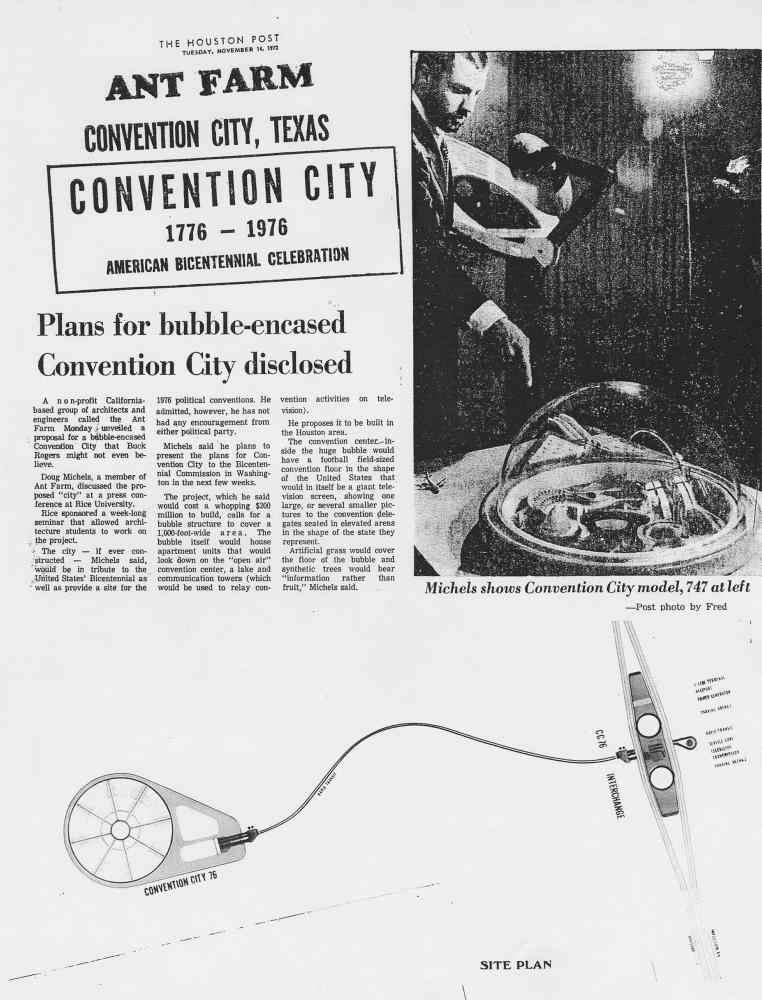

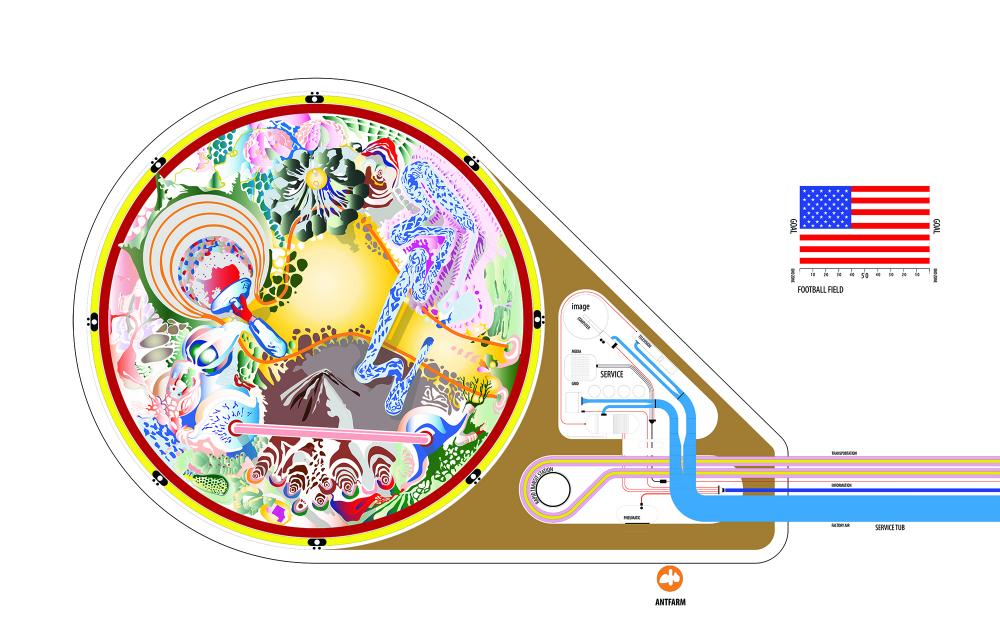

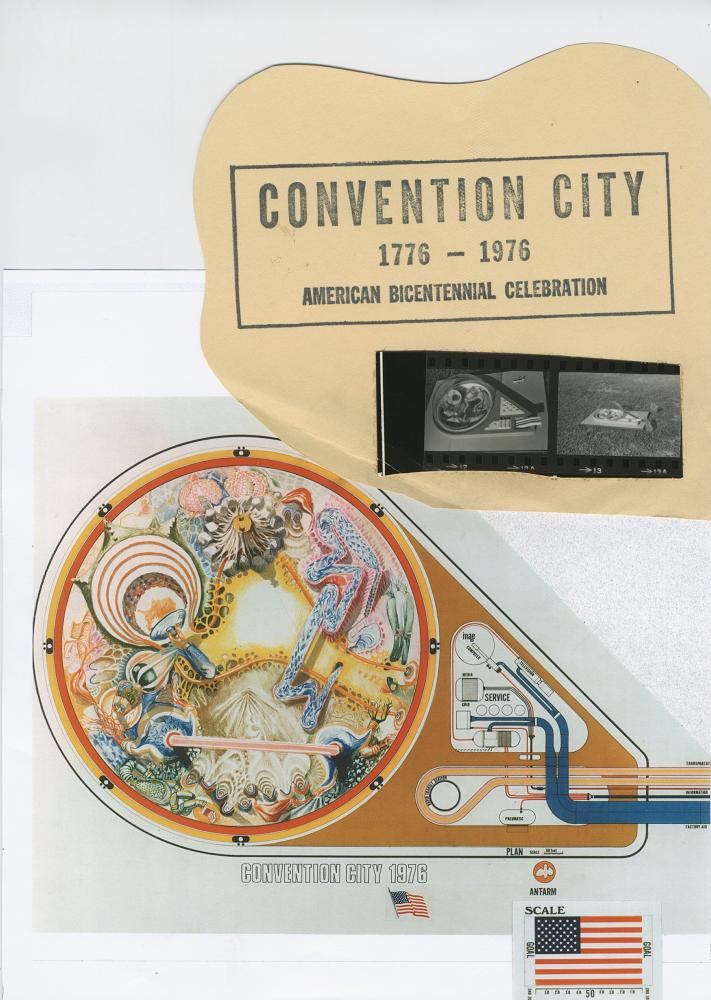

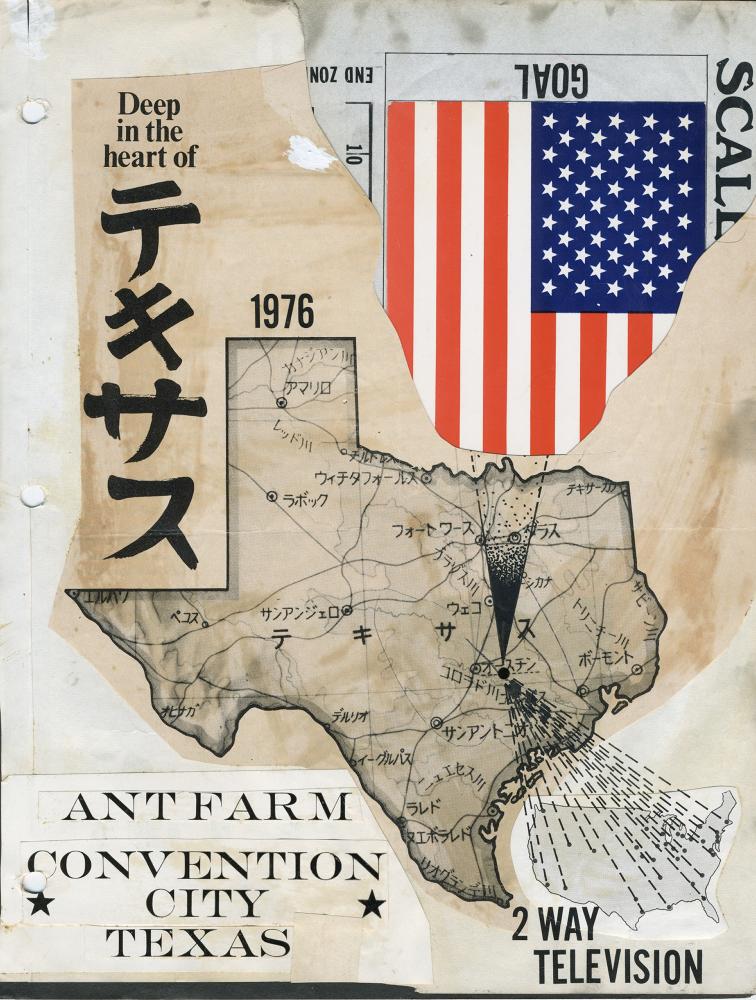

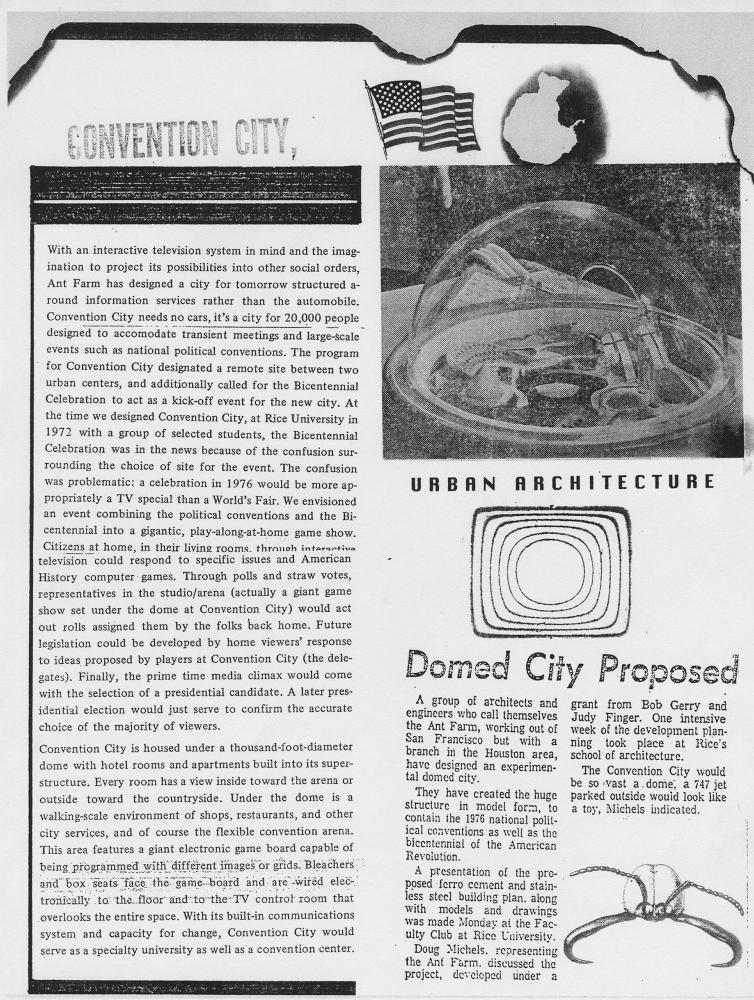

In 1972, Ant Farm developed a proposal for Convention City, a new domed city for televised political events. Led by Michels, it was realized with students at Rice through a weeklong workshop. After a staged press conference, the work then appeared on the pages of the Houston Post. Images of the project and discussion of its relevance are included below.

New York-based architecture office WORKac has productively engaged with both the creative legacy of Ant Farm and its surviving members. (They were also the architects for the renovation of the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston, completed in 2012.) In 3.C.City, their contribution to the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennale, the office redrew three of Ant Farm’s projects and transformed their explorations into a new design, a “vessel, a research lab, a conference center, and a vehicle of dreams—a floating city designed to facilitate dialogue and debate between people and other species.”

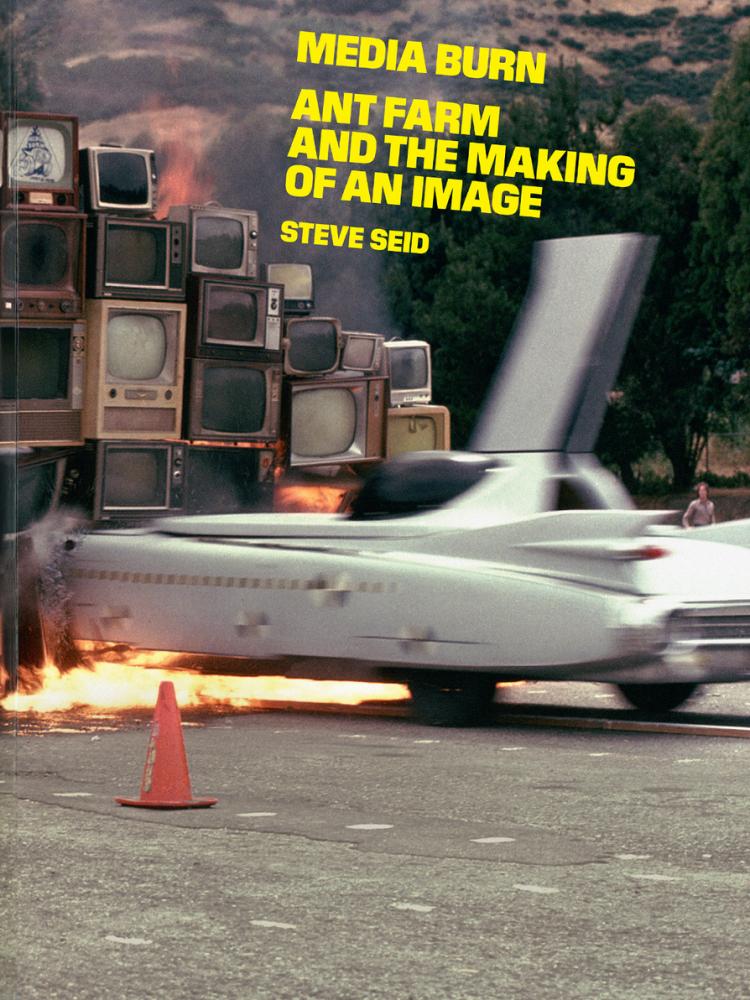

Interest in Ant Farm’s work grew even after the group ceased operations. Their media engagement foreshadowed many of the conditions of 21st century contemporary life. While the group focused in part on the effects of television, even greater intensity should be directed towards the impacts of social media today. As part of the exhibition “The Utopian Impulse: Buckminster Fuller and the Bay Area” at the SFMOMA in 2012, Lord and Schreier revisited Convention City and made an updated video. This spring, Ant Farm’s Media Burn is further documented through the recent release of Media Burn: Ant Farm and the Making of an Image by Steve Seid, co-published by Inventory Press and RITE Editions.

The text below is reproduced from the third edition of WORKac’s 49 Cities, published by Inventory Press. The book collects data about cities, real and proposed, and examines the form of settlements through an ecological lens. Lord and Schreier present Convention City and then Lord joins Amale Andraos and Dan Wood of WORKac in conversation. As Andraos noted in “Hacking Ant Farm,” a conversation with Lord related to the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennale, Convention City is the smallest of the cities in the book and boils down “the city to its essence—the political arena of the Greek democracy.” Additional archival images were recently provided by Lord.

Cite is grateful to all involved for their generosity in making the text and images available for this revisitation. —Jack Murphy

Convention City

After the 1972 conventions, in the fall Ant Farm went out to Houston, where they were living, and proposed a workshop with students at Rice University, to design a Convention City that would be self-contained and would have the flexibility to house different types of conventions and that would also be a TV studio. The idea was that it would be both a permanent city and a temporary city of hotel rooms where people would come to the convention.

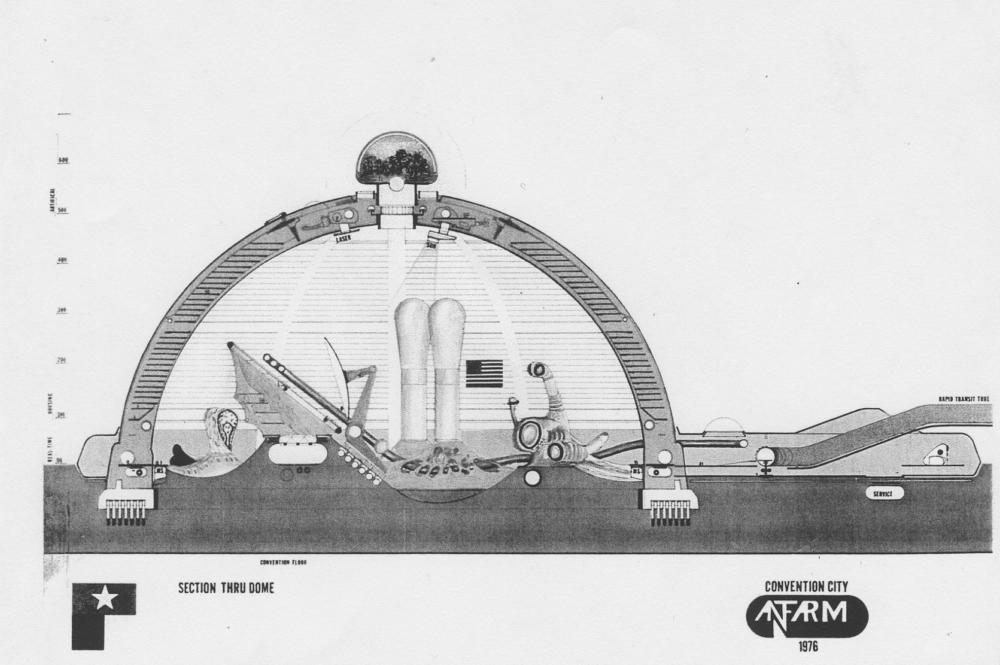

Curtis Schreier (CS): What people don't realize was the dome that we showed surrounding the city was actually the hotel rooms themselves. It shows in the section but does not show very well in the model. The 20,000 delegates were in the hotel rooms, and they were the citizens of the city.

Chip Lord (CL): They'd have a balcony to look down from the dome to the floor of the convention, which we made into this psychedelic landscape. It's a very dichromatic model. You can assess the scale of the project from the 747 we included in the renderings.

CS: There were platforms for the delegates that were shaped like the states where everyone would stand. One person, representing the people behind them, would work their way to the front of the delegation and that person got to go down the escalator and stand and vote on the issue. The voting floor was supposed to be a sensitive floor.

CL: An illuminative, responsive, programmable floor.

CS: The delegates would ride on little electric bumper cars. That was the voting process. You would have collisions with others with different ideas and be able to push people into certain corners.

CL: This is at the core of the idea. The conventions are already like game shows; they build very temporary sets just to be seen on camera. Convention City presented an optimized platform for a new way of voting. We also thought it would be interactive with people at home, who could talk back to their TV. Maybe they could have input remotely.

CS: In Convention City, the public was also able to see what was going on, on the floor, from a people-mover that had viewing areas as it swirled around the top of the dome. There would be a certain amount of interaction, but not completely, with the delegates, there might be common lounges.

There'd be a lot of history. Partly world's fair and partly bicentennial celebration. The space program was really big. The lake we called Mercury Lake after the astronauts. We were going to actually make it so it looked like it was silver. We couldn't use real mercury but that would have been cool.

It was a celebration. There's also a section that looks like a giant tree trunk that was supposed to trace all the roots of American ancestry out as an exhibition. There were all kinds of things that were designed.

CL: It was a one-week workshop, and during that time the model was made as well as all the drawings. At the end of the workshop, we put the model on a stand covered in American Flag bunting and held a press conference.

CS: It was part of the performance to surround the model with the red, white, and blue bunting. We presented to the press as if it were an Americana thing, rather than a high art thing.

CL: This was one of Doug Michel's great abilities as a publicist. It was a matter of writing a press release and sending it out to every TV station and newspapers. It gives you an insight into how things like that turn up as news items. So, it was a crazy idea in one sense but then it was taken seriously because it was written up in the press. The paper wrote it up as “these guys are ready to go to the next stage of design as soon as they find a developer.”

And you know, in Houston, Texas a developer might well have come forward! We needed the newspaper for that and we had some calls I think, but nothing ideal, unfortunately.

Dan Wood and Amale Andraos in Discussion With Chip Lord

Dan Wood (DW): I love the contradictions in the project, which really stem very directly from your experiences at the conventions in 1972, and the idea of the political convention in general. On the one hand you have this very temporary, Potempkin-esque situation of something constructed very cheaply and quickly. On the other hand, through graphics and symbolism a very strong image of power and the political process is created. That's why your final presentation of the project with the bunting is so great, it transforms the project into something very American and something truly political.

Amale Andraos (AA): I was thinking of how you started your presentation by describing the modesty of interventions versus the scale of the ideas. This can be very strategic. A stealthy network of small nodes can produce big changes.

But you still go for the big scale: this amazing landscape under an enormous bubble of hotel rooms. And in the end, with the press conference and the bunting, there's still this visible, strategic intervention added. How do you see the two together?

CL: Well, if you contrast Convention City with the Truckstop Network, for example, one is completely conceptual and the other one is completely practical. For Ant Farm at the time, the two approaches don't necessarily ever come together, they're really different. I think today the question is really how do you make architecture for the virtual, or in the virtual? I don't know the answer. At the same time we have more capability to build large places and large spaces. It's probably important to try and consider how to integrate large public spaces with handheld capabilities to enhance a sense of social democracy. That seems kind of obvious but it's still good to state it.

AA: The fact is that, with the Arab Spring for example, we can see that with all the organizing done through social media, people still needed to consolidate in a public, physical space like Tahir Square. The virtual still hasn't replaced the physical, they complement each other. That's why Convention City is so interesting, and so visionary. It illustrates this notion that in the end the physical has not been entirely displaced but can be complimented or enhanced through interactivity and media.

It is interesting to compare Convention City with Fuller's Dome Over New York project, which encloses the urban to somehow make it more of a self-sustaining system. Convention City, on the other hand, encloses this amazing representation of landscape. Do you have sense as to why you felt that the idea of a landscape was so important to the project?

CL: I think it was a form of expressionism really. An expressive sculptural landscape seemed to best represent the sense of multiple permutations of what could happen, to emphasize it was a transformable and active space.

AA: The other thing that's interesting is the site plan drawing of Convention City. In contrast with many of the other projects in 49 Cities, Convention City is shown plugging into something with a kind of umbilical cord.

DW: There’s the city, the plug, and the idea that there's the rest of the world beyond, which you have to leave and enter into this new world, while still remaining connected.

CL: It's connected to a highway, a core that accommodates both physical mobility and telecommunications capability. That's why it can be positioned anywhere in the world. The idea that you can ignore what's around you, the environment, is obsolete. You can't really do that unless you make it a capsule that's also completely off-grid and self-sufficient and so on.

AA: We also asked this question in our conversation with Michael Webb. He admitted that at the time, the context and environment weren’t ever present in their cities, it was the pop appeal of disposability. So even though it was called the “plug in city,” the plug was never shown.

CL: Right. Plugged into what?

AA: Exactly. It simply wasn't a concern. I think that there's a shift in your work, just in that drawing it’s very clear that you're never unplugged, or if you are, you have to think about how you could be.

AA: I think this also relates to this notion of the disposable convention, the creation of a stage set that gets thrown away.

CL: These conventions are like instant sickness. It might be 30,000 or 40,000 people coming and inhabiting this area for a short period of time and then leaving.

DW: When we talked to Michael Webb, we were asking why cities? He said simply that everyone was doing it! You had to have your city. I was wondering whether that was part of that Ant Farm had done so much and at some point you thought, we have to do a city as well?

CL: It really came out of the experience of going to the convention in 1972. It was a simple leap to turn it into this project. Also, “Convention City” is a good name. The idea was essentially putting everybody in one big dome and having no cars. That was the organizing principle. It doesn't necessarily take on the full responsibility of what it means to these 20,000 people. I suppose everybody who lived there would be working in the service industry of the convention. Is that the kind of city you want to live in? We didn't answer those questions.

DW: I wanted to talk about the idea of the project as satire. I think Convention City can definitely be read as political commentary, and I think probably a lot of people do. But I get the feeling that Ant Farm did not.

CL: It's maybe not the most overt presentation of satire, or irony.

I feel that satire implies more of an “in your face” gesture. Of course there was a sense of satire simply by the idea of the world's largest TV studio. But we took that initial gesture and created this city with more than one energy, as we were saying. So would that be satire?

DW: You have described Ant Farm as hippies with lab coats. I think it is funny that in that picture of Doug Michels it's very hard to tell which one is the hippie and which is the CBS cameraman. I know the idea of the counterculture was very important to you. Did you always feel that the counterculture could eventually become the culture and therefore truck stops, and the internet would become less radical, but very real, versions of your proposals?

CL: It's probably apropos that the central tension of our practice was whether a true alternative culture could be created. That was a larger project, the larger goal.

We have different forms of realization. Tom Hayden who was a radical became a politician, radical food people have become restaurateurs. A number of others were handicapped by the desire and never could reenter into society.

There isn't such a thing as a true alternative culture. To create something that’s truly an alternative is very challenging. We have to at some point interface with the existing culture.

I think within Ant Farm there was a bad boy aspect—just do things that would make an impact or send a message as an affront to the mainstream culture. At the same time, at any moment a potential real client might show up and we always felt maybe we can make it work with this client, because they are actually interested in funding the ideas.

DW: It is something that always comes up when talking about 49 Cities—to what degree were these proposals meant to be realized? For us, in the end, it does not really matter. These are ideas that have helped shape reality, and vice versa. Paper Architecture can sometimes have a bigger impact on the broader culture than built architecture.

CL: When Ant Farm started out, we wanted to be Archigram architects. We wanted to be part of this underground culture that was opposed to the mainstream culture. There were underground newspapers and underground radio, underground art. An Ant Farm is “underground architecture”—a very literal reaction.

It was also a good metaphor for what we were engaged in because the ants work collaboratively and the shapes they make underground are pretty amazing. We didn't know this in1968 but there's been more recent research into the ant colonies. It describes a collective mind, a collective intelligence the ants have. There are billions of ants in the world. It's a species that's very adaptable, very enduring in terms of their habitats. They also make amazing architecture, huge structures.

This idea that the colony has a greater mind than the individual ant is pretty interesting, all of the individual actions function for the good of the colony. Ant Farm was a collective—a team, with a kind of collective mind. At a larger scale, I always felt that by acting as visionary architects, we might be part of an even larger intelligence, the collective cultural intelligence. That is what actability is about; you're participating in a larger building of knowledge that's both for your benefit and for the larger society.

WORKac creates architecture and strategic planning concepts at the intersection of the urban, the rural and the natural. Embracing reinvention and collaboration with other fields. The practice strives to develop intelligent and shared infrastructures and to achieve a more careful integration between architecture, landscape and ecological systems. WORKac holds unshakable lightness and polemical optimism as a means to move beyond the projected and towards the possible.

WORKac was the #1 design firm in Architect magazine’s 2017 Architect 50 and the 2015 AIA NYS Firm of the Year. The firm has achieved international acclaim for projects such as the Edible Schoolyard at P.S. 216 in Brooklyn, the Kew Gardens Hills Library in Queens, and the Stealth Building in New York. Current projects include a masterplan for 60 villas on a waterfront site in Lebanon, a public library in Boulder, CO and a new office building in San Francisco.

Amale Andraos FRAIC is a co-founder of WORKac and a principal of the firm. She is also Professor and Dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation. Andraos is committed to design research and her writings have focused on climate change and its impact on architecture as well as on the question of representation in the age of global practice. Her recent publications include Architecture and Representation: the Arab City, co-edited with Nora Akawi, as well as We’ll Get There When We Cross That Bridge, a duograph for the practice in conversation with Dan Wood. Andraos has taught at numerous institutions including the Princeton University School of Architecture, the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the American University in Beirut. She serves on the board of the Architectural League of New York and the AUB Faculty of Engineering and Architecture International Advisory Committee.

Dan Wood, FAIA, LEED AP, is a co-founder of WORKac and a principal of the firm with extensive experience leading large-scale and complex US and international projects. Wood was the 2017 Gehry Chair at the University of Toronto Daniels School of Architecture as well as the 2013-14 Louis I. Kahn Chair at the Yale School of Architecture. He is currently an adjunct associate professor at Columbia GSAPP and has taught at the Princeton University School of Architecture, Penn Design, and the UC Berkeley School of Environmental Design, where he was the Friedman Distinguished Chair. Wood is a licensed architect in the State of New York and Rhode Island. His publications include 49 Cities and Above the Pavement the Farm!, co-authored with Amale Andraos. He is currently the Vice President for Design Excellence on the board of the New York AIA chapter.

Chip Lord grew up in 1950’s America, a place that has been a sometimes source of inspiration in his work as an artist. Trained as an architect, he was a founding partner of Ant Farm, with whom he produced the video art classics Media Burn and The Eternal Frame as well as the public sculpture Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, Texas, and the House of the Century, outside Houston.

His work crosses documentary and experimental boundaries and moves between video, photography and installation. He often collaborates with other artists. Ant Farm Media Van v.08 [Time Capsule], a collaboration with Curtis Schreier and Bruce Tomb, revisits Ant Farm’s 1970 Media Van and brings it into the 21st Century. The installation posits a “post-internal combustion vehicle’ as a space for networking around a “Media Huqquh” and in the process creates a digital time capsule. An abiding interest in the complex culture of transportation systems inspired The Executive Air Traveler, 1980, a photo series; Airspaces, 2000 – 2011 and To & From LAX, a public video installation. Lord authored Automerica for E.P. Dutton (1976) and the car as subject also "drives" MOTORIST, Road Movie, and The New Cars, 2012. His lecture The Long Goodbye to the Automobile integrates seven projects and speaks to the future.

Chip Lord’s work has been exhibited and published widely and is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, The Tate Modern, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the FRAC Centre, the Pompidou Centre, and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. He is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Film & Digital Media, U.C. Santa Cruz, and has also taught in Architecture at CCA and Columbia University GSAPP. He lives in San Francisco.