Buildering: Misbehaving the City looks into our shared spaces. With very few exceptions, the works are set in cities --- specifically, city streets. A wall text opening the show mentions "modernist architecture's mechanical segregation of work and play" (ref. Alison and Peter Smithson). A touchpoint for me in the show is Bernard Rudofsky's 1969 book, Streets For People. He critiques the American city for what it isn't: human-scaled, inhabitable. Rudofsky sees an American society, going back to the 1700s, in which "our streets have become roads." My medicine in childhood for the condition Rudofsky describes was Martha and the Vandellas' "Dancing in the Streets." The song took off with an ecstatic roar and promised freedom. Very meaningful in 1964, when the American city street was the scene of riot and fear. The song offered a big reconciliation.

A thread throughout Buildering is play. The tools are disruption, rearrangement of attention, and surprise. Creative play emerges as a way of re-entering our shared space on our own terms. The international artists of Buildering find the human form, the space one takes up, the finger's touch, in the vacant space around us. They repopulate our city world with relationships that we hunger for.

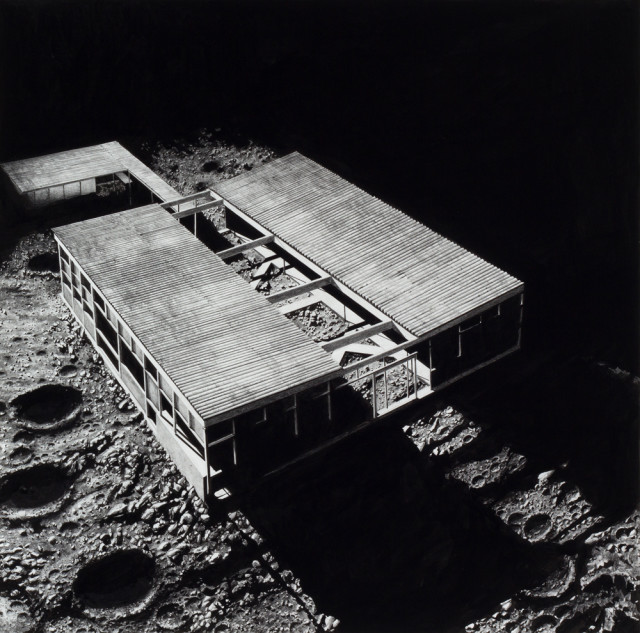

There is such an ache of longing in this show. Alex Hartley presents four C-type photos with highly crafted constructions crusted on their surfaces with fully illusionistic results. There are dwellings, a hut, and a beautiful observatory set in remote, depopulated landscapes. These are among the few works not in and of the city. I'll mention their titles:

Imagine there is a God

If only it could be this way

Outpost

Waiting for Daylight to End (Kaczynski's Cabin)

This last makes reference to the Unabomber. I am touched on the nape of my neck by the ghost of this maverick serial killer who advocated a nature-centered anarchy, here on a sunny day at the University of Houston campus.

For me, the most poetic work in the show is Shaun Gladwell's video projection Pataphysical Man. The image is projected far above the floor in the Blaffer's tall central space. An upside-down image of a fit guy doing a continuous spin on his bike-helmeted head. Inverted, we see him upright. He's picked one move out of the breakdancing repertory. I am moved into dream space by the image's elevated slow motion. Our "Pataphysical" subject is managing his spin so well, it appears effortless; he's free; counterbalancing his body weight and free to move. Pataphysical Man shifts me out of a practical mode. This is Tai Chi time, meditative and densely energetic.

Autocorrect doesn't like Gladwell's title, Pataphysical Man. Pataphysics is a truly absurd science, invented by a supreme prankster, the playwright Alfred Jarry. The literature of Pataphysics, in Latin, is as detailed and kooky as I'd wish. Its members have included Ionesco, Ernst, Miro, and Duchamp. The modern college's many branches are overseen by a crocodile. This Pataphysics motto is meaningful to this show: "Eadam mutate resurgo," or "I arise again, the same though changed".

Etienne Boulanger's photos voyeuristically record his brave and abject attempt to live in Berlin for two years "without an address." He documents himself occupying body-sized nooks in the city. That is all.

When we gather together in our efficient high-density settings, we lose all belonging. Boulanger's deadpan play brings his body's scale and experience back into the city. He takes a lively approach to a great loss of connection. His modest photos are healing for this viewer.

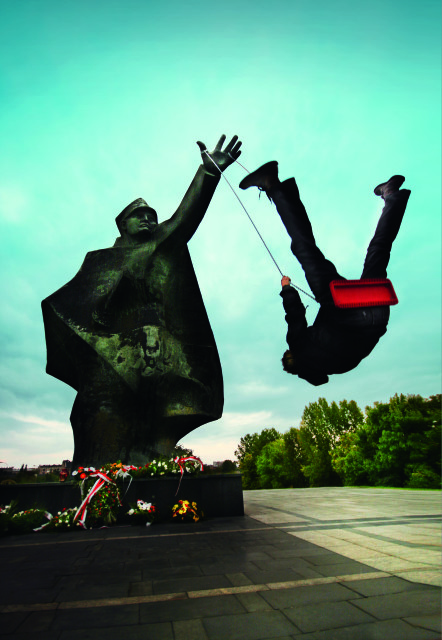

I'm describing many live-action videos and photos of performance actions here. There were digital animations on screen in the show, but I must have ignored them. I sighed gratefully for the lack of didactic works, which my prior image of the show had feared. Instead, here was the spirit of Yves Klein's Leap into the Void. I feel that the work in a variety of media in the show succeeded as sculpture. It rearranged my behavior and habitation in space, even if through the voyeur's mode of the screen. The halls of the Blaffer echoed with a complex soundscape. Not far from the door is UH faculty member Abinadi Meza's sound installation. He activates the window glass as speakers. The audio place he creates is subtle and invites me to walk and explore. I would dearly love this installed in a downtown office lobby.

One way we recover our senses is by making and viewing drawings. Alison Moffett does some lovely drawings in which she collides ghosts of minimal cubes with derelict and overgrown sheds. An artist of collision and opposition, Moffett, working with graphite, is eerily delicate.

As documents of secret or private performance, many works in the show also measure our separation from artist and event. Given the need for me to be a voyeur, how wonderful to happen on Ivan Argote tongue-kissing a subway handrail. He even gave a charged look at his stainless love before he engaged and after he separated. "Kissing this bar in such a passionate was a reconciliation gesture for me."

Reconciliation. Buildering is a playfully earnest and existential struggle to find our bodies' and spirits' habitation in the city's voids.

Buildering continues at the Blaffer Art Museum through December 6, 2014. David Miller is the proprietor and lead craftsman of Dungan Miller Design, Ltd.