Parking at Whole Foods and Saturday traffic to Galveston would be exacerbated were the whole world to live in Texas, I imagine, but “this scenario . . . illustrates the vastness of our planet’s land area and the power of density to promote more efficient land use.” In A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America (Metropolis Books, 2014), Vishaan Chakrabarti doesn’t propose this “improbable scenario” for Texas literally. He does argue, however, that almost all of our problems are due to the country’s, and now the world’s, “suburbanization” and that denser cities everywhere, in which everyone could walk or ride a subway, would be better for all of us: ecologically more responsible, with a much more efficient use of energy, and greater happiness all around because, for instance, people in cities are --- he has statistics to show this --- less obese than people in the car-fraught suburbs.

A Country of Cities is a manifesto, not a dispassionate analysis. Its title alone implies a degree of reorganization that would realign the long historical opposition between the country and the city. Raymond Williams has exposed the problems in this kind of grand, binary thinking in his book The Country and the City, where he assesses the damage done by England’s long portrayal of itself as a pastoral paradise. In this myth, real rural poverty has no place. And in Chakrabarti’s new cities, poverty, crime, drug violence, and the indifference of individuals to the ideals of planning all seem nearly invisible.

Chakrabarti is a chaired professor at Columbia and a partner in the firm of SHoP Architects. His argument is supported by other professional studies, many statistics and graphs, and his own boundless optimism. But his optimism’s rhetoric makes his arguments seem less substantive, less convincing, and harder to hold onto than they should be to be entirely effective. Here is an example:

If we strengthened home rule in our cities so that they were free from state legislatures to govern and invest resources as they saw fit, we would likely see a tremendous and sustained surge in our national economy given the track record of prosperity that cities have already established. For this reason alone, the United States should adopt policies that unleash our thriving urban economies. But beyond our self-interest we should also do so to become an exemplar for other modernizing societies that have adopted sprawl in a manner that, like our own, could lead to disastrous environmental consequences.

“If,” “would likely see,” “should adopt,” “should . . . to become an exemplar” are subjunctive and hortatory verbs in sentences that are not in the declarative mood declaring facts. The effect is too moralizing.

And after the creation of all these new city-states that are magically free from their state legislature, cities such as New Orleans and Detroit, which have always resembled the city-states of the Medicis and the Sforzas, can also become models for Sao Paulo, Lagos, and Mumbai, cities that hang on our every word for leadership. Because American cities have both a great “track record of prosperity” as well as the sprawl “that could lead to disastrous consequences.” Isn’t he contradicting himself with the great track record that can lead to disaster?

Here is Chakrabarti in another optative mood with his definition of infrastructure --- by which he means much more than public transportation, communications, water and sewage systems, electricity, and data. (“Data” is infrastructure?) He means “fundamental social systems, such as schools, cultural centers, health-care facilities, and parks. This expanded definition represents an ‘Infrastructure of Opportunity’ --- the means by which people can attain their aspirations with increased access to employment, education, recreation, enjoyment, and health.” Cities can be planned for centers such as museums and concert halls, but I don’t think they can be planned for “culture.” “Access to employment” can be planned, too, but planning does not simply guarantee jobs to be accessed. And access to “enjoyment” is . . . what? Yards for gardening? Cheaper prices at Whole Foods? More bars on Westheimer, but without the parking issue, bad enough already, of the world’s entire population living here? In any case, “Infrastructure of Opportunity” is an awful phrase.

If a manifesto is a statement of principles and goals, and maybe a call to action, it’s not required to be the whole blueprint of practical strategies and the means to those ends. I don’t know if the whole plan Chakrabarti needs could be drawn anyhow, because it would have to be a total plan for reorganizing the politics of money, from fiscal policies and legislation at the national level to local taxes and allocations. At the moment, our governments, on almost every level, seem incapable of cooperation and incompetent of imagining any needs but their own in the next election. Our infrastructure everywhere needs rehabilitation, and neither the Gulf Coast, devastated by Hurricane Katrina, nor the vast damage done by Superstorm Sandy to the New Jersey Shore have been repaired. It makes America seem old and enfeebled.

Like most of us who read Cite, I already subscribe to the values of urbanism that Chakrabarti celebrates and believe, as he and Edward Glaeser do, that the city is our greatest invention: it has made us, in Glaeser’s phrase, “richer, smarter, greener, healthier, and happier.” It is the altitude of Chakrabarti’s sweeping claims, his certitude that all of us will respond in exactly the same correct way to the changes he wants to see, that bother me. There is in his argument a naivete or an even more discomfiting “totalism.”

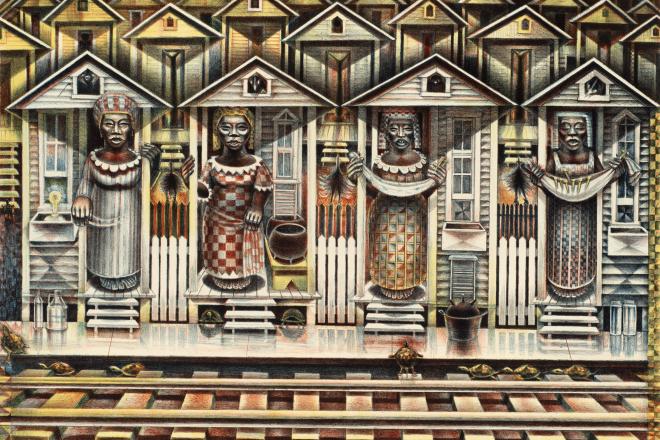

I often think of the city as an uncountable number of unimaginable strangers, all of them with a different characterization of the world that expresses the core of their individuality, their autonomy, their essential right to a democratic social order. It is hard to plan for them. This is what makes A Country of Cities hard for me to buy into, despite its high energy, impressive good faith, and its very cheery graphics. Every even-numbered page, it seems, pops up with high-quality photographs or with charts and graphs that feel like cartoons designed to make all the information more entertaining. The color green seems to dominate here and, in this context, it’s a very political color. Very hopeful too.

Terrence Doody is Professor of English at Rice University, and the author of Confession and Community in the Novel and Among Other Things: A Description of the Novel.

More >>>

"Building Hyperdensity and Civic Delight" by Vishaan Chakrabarti, Places, 6.13.13