The Champs-Élysées, Broadway, the Passeig de Gràcia, and Post Oak Boulevard. One of these look out of place? Alex Garvin, renowned planner and Yale architecture professor, doesn't think so. He has said the new Post Oak Boulevard will be "the grandest boulevard in the United States" and wrote about the street in his book What Makes a Great City?. With recent progress on expanding sidewalks, planting 800 new live oak trees, and building dedicated bus lanes, and with the March 2018 opening of Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta's Post Oak Hotel quickly followed by Texans owner Robert McNair's announcement to bookend Post Oak Boulevard with a $500 million mixed-use development of his own, Garvin's praise does not seem quite as far-fetched. The infrastructure project, however, was met with organized opposition and a lawsuit that challenged the constitutionality of the key financing mechanism. The project is paid for in part by Uptown Houston, which was authorized by the Texas state legislature and city to levy a property tax increment. In this edited interview, Andrew Albers talks with Garvin about what makes great cities great, the benefits of quasi-governmental institutions, and the future of Houston's Uptown. Albers is a vice president with OJB Landscape Architecture, a lecturer at Rice Architecture, and recipient of the 2018 Ben Brewer Award from AIA Houston.

Andrew Albers: In your book, What Makes a Great City?, you describe six key elements of great cities. The elements that resonated with me were that it must be open to anyone, it has something for everybody, and it needs to nurture a civil society. You cited examples from the expected places in Europe, but you also drew on the Beltline in Atlanta and Uptown in Houston.

Alex Garvin: I was brought to Atlanta by the Trust for Public Land because they felt Atlanta had a deficit in parkland. Atlanta had three and a half percent [total land area set aside as public parks and open space]. The leading three cities, Boston, San Francisco, and New York, were in excess of 20 percent depending on how you counted it. I knew about [Ryan Gravel’s work on] the Beltline. I decided that was a way to proceed because you could create a system of trails. I hired Ryan to work for me. It was a really daunting problem to figure out if you could create a continuous trail system. I went up in a helicopter, which is what I do whenever I do these things. I identified the Bellwood Quarry and what is now the Historic Fourth Ward Park. I was inspired by Frederick Law Olmsted that this should be an Emerald Necklace. Bellwood Quarry will be the largest park in Atlanta.

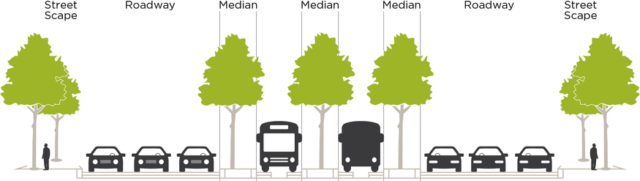

Your question about nurturing civil society … that really is at the crux of the book. You picked very well in doing that. The thing that I was really quite struck with Uptown Houston is that it also began with an automobile-oriented city. I don’t see Houston for the foreseeable future moving away from the automobile. I had been watching this street transform, you can see from the pictures I took, from a dusty arterial to a grand boulevard. They do something quite significant by putting in the bus line down the middle; that means people can come by bus, who don’t have automobiles because they are handicapped or don’t have money, can transfer to a bus that goes down Post Oak Boulevard. More important, it allows people to use all the things that are there. At lunch time, you can leave your office, go downstairs, get on the bus, and go to a restaurant or go to the Galleria or go to one of the other stores and buy something. At five o’clock, people, at so-called happy hour, can leave their offices and go to a bar and hang out. It opens opportunities. The bus line that goes down the center is a critical part of it.

Those capital improvements that open a dazzling street, or that will be a dazzling street ten years from now, those are very important characteristics. How does this nurture a civil society? Once you have people on the sidewalk that can’t avoid one another, you are going to have a mixing valve that is for everybody that goes up and down Post Oak Boulevard, the people who work there, the people who are going shopping there, the people who live there --- after all there are already several thousand condos on that axis -- tourists who are there for hotels, and that’s the very essence of a civil society, where you have to encounter people who are different than yourselves every day all the time.

AA: The funding for Uptown is coming from the TIRZ (Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone). At the end of Annise Parker's term, Memorial Park was brought into the Uptown TIRZ to create a mechanism for funding the park. One of the questions that we have is that the project at Buffalo Bayou and many of the great urban landscape projects that are happening here in Houston between Bayou Greenways 2020, Buffalo Bayou, Memorial Park, Hermann Park, the work in Uptown, these are all relatively central, with the exception of Bayou Greenways, and are funded by TIRZ or public-private partnerships. Growing up in the suburbs outside of these core portions of the city, looking at the most recent election, if you looked at the results, urban centers voted one way and beyond the urban centers voted a different way, is there a way creating great cities or nurturing civil society could unfold beyond the urban core?

AG: First thing, you need to separate suburban areas from exurban areas, that is to say the near suburbs are one situation and I don’t think they voted the same as rural areas. Gerrymandering, attitude. I don’t think you can lump the suburbs into either of the two categories. Having said that, we have a phenomenon in the US, really since the Second World War, and that is, government has been choosing to fund things that it never did before in increasing amounts, whether we are talking about welfare, social spending, and so on, and especially the inner ring suburbs wanted to have better services than they were getting. Garbage collection twice a week, not just once. Better police patrols and so on. Pretty soon governments were providing those services, that’s where the votes were. In order to do that, you have to do one of several things. Either you have to increase taxes, which no one wanted. Or you had to cut the budget, which nobody wanted. Or you had to transfer the services from areas that were being serviced to areas that were demanding improved service. This latter affected every part of the US. The first thing that they cut --- this goes to the heart of my profession --- was planning. They cut planning. The second thing they cut --- parks. None of these could be argued as essential when you have a budget crisis. If you cut spending on parks, the other thing you can cut, you don’t need garbage pickup every other day in the business districts.

The only people who could fight back were business owners and the property owners, and they formed business improvement districts or what you call TIRZ areas. The park enthusiasts followed suit immediately and started conservancies. The first, the model, was the Central Park Conservancy, which was formed around 1980 during the administration of Ed Koch. Now we have these conservancies everywhere because government has withdrawn those services. What we have effectively done in the country is dealing with the inadequate government services is creating new institutions to provide them. You call them public-private partnerships, that’s what everybody uses, it’s a quasi-government. And the people who benefit are choosing to tax themselves for it, whether by donation or by an actual tax surcharge. And it’s in that context that all of these park systems, whether it is Buffalo Bayou or Memorial Park are part of the same process, and the initial action of that sort was Uptown and the TIRZ. And I think not ironic, it is in fact brilliant that Memorial Park is grafted on to an existing system like this.

AA: Do you think that models involving quasi-governmental systems that require residents to opt in are effective? Do you think that these particular models in Houston fail at remaining completely democratic?

AG: In every place what you have, it’s being run by the people who pay the money, call it democratic or not. If you say the property owners in the TIRZ are voting for it, is that democratic? They are the property owners. They are voting for services they are paying for. The problem we have in the country is that we don’t want to pay for the services we are demanding. That’s the whole problem. I understand the democratic overlay you are talking about. I especially understand that persons of very low income are not using these facilities all the time. They have trouble getting there. They don’t have a car. That’s where a bus system comes in to help them. Democratic? I’m very practical. If it works, let’s do it. If it doesn’t work, let’s get rid of it. That’s my view. Government services weren’t working. Replacing them with a service institution makes sense to me. I know this isn’t politically correct, but that’s what I think.

AA: In addition to governmental and quasi-governmental means, private developers also want to create great places. Would you speak about your Tessera Project in Austin?

AG: That’s an interesting project. I was hired by the Gerald Hines Company. They had a plan for a 700-acre subdivision. They wanted what they called green design because they thought that that would get approval more quickly from local officials. And they asked me to come. I went out in a helicopter. I combed the site with the people working on it. I went back to my office in New York and we came up with a scheme that I thought achieved all of this. The idea was, the scheme they had was entirely made up of cul-de-sacs. The first thing I said was that we are not building on any steep slopes. That’s expensive. You don’t want to excavate. So wherever we have steep slopes, I want to turn that into public realm. That becomes a park framework. Second thing was, it was on the edge of Lake Travis, and I said the entire edge of Lake Travis should be for public recreation. For people who live there, so I wanted to have a roadway that went on the edge of that between the beach and where everyone lived. No cul-de-sacs.

And the next thing I said was that you want to maximize the views. This is a sloping site going down to Lake Travis, and there were wonderful views. So we found where all the views were and we tried to locate things there. We created a street system that respected the topography and essentially connected everything. When we laid everything out, we had a completely different kind of subdivision. I vividly remember going to my client’s office in Downtown Austin. They were dazzled. And their number person looked up and said, our current plan has 1,600 rooftops. How many rooftops have we lost? I looked at him and said, this plan has 2,300 rooftops. [Laughter from Andrew.] I think it is quite possible to do these things if you follow legitimate principles that have to do with topography, with drainage, with views. I was thrilled to be able to do this plan. I never thought in my life I would be doing a suburban subdivision.

AA: Speaking of housing, there have been questions about the Beltline in Atlanta. There is concern that it is so successful that people are going to be priced out of the neighborhoods along the boundaries. Some of the neighborhoods are historic African-American neighborhoods whose identity will be challenged by these changes. There has been talk of affordable housing associated with the Beltline, but has it been built into the project?

AA: If you are going to have affordable housing somebody has to pay for it because it requires a subsidy and nobody is ready to pay a subsidy. The federal government has withdrawn from this. We can’t get Congress to approve any subsidies in any reasonable number. I think we have got to look at the provision of affordable housing as an absolutely separate item. If you want affordable housing, you have to pay for it. You have to create adjacencies that build it. We should not be demanding that somehow that people who are building a house have to provide affordable housing on their property. I don’t think that will get us anywhere.

AA: Do you mean inclusionary zoning policies?

AG: Inclusionary zoning policies work in the following situations: First of all you have to have high enough market rents so you can have a cross-subsidy for the low income units. In order to have this you have to get the most expensive land in the territory, which means you are producing the least amount of affordable housing, and you are only doing it in particularly high income area. That leaves out the bulk of the US. I think if you want to have affordable housing, we have low-income housing tax credits. We have lots of other ways of doing it, but to assume you can do it as a cross-subsidy is a mistake because we will not get enough of it.

AA: Urban projects such as the High Line and the Beltline [among others] have proven transformational for cities, but it seems that cities are caught flat footed when the change in values cause affordability challenges. Why are we always behind the game when affordability becomes an issue at the end of the process? Can’t we build the subsidy for affordable housing into the increment?

AG: No you can’t. Because if it is going to be successful, it will be because the values are very high. If you want to get housing, use the tax funds to pay for it. That’s the fastest way you can do it. Then you can distribute it wherever you want, not just high-income areas.

AA: Outside of housing, some of the urban spaces that contribute to making great cities are being created by private development. Is there a way to incentivize plazas and public spaces to be truly public, within the public realm, instead being a privately held plaza that, in truth, only appears open to the public?

AG: We have a long history in New York City of privately-owned public space in the form of plazas, because in the 1961 zoning ordinance we provided in high-density areas a twenty percent bonus for buildings which set back from the street and increased the amount of sidewalk space. We called it a plaza. In some cases, they really are plazas. In many cases, it is leftover space. We now require a sign to be put up saying that these are the hours it must remain open to the public because it is a public benefit. But we are not very good stewards of this space. I’ll give you an example. Any number of them have bollards and huge planters that keep people from using the open space because allegedly there is a security problem. The insurance company wants to make sure the truck bomb isn’t going to destroy the building. None of them know exactly what they are protecting themselves from. But they are now taking away public space, which they got a bonus for. They got 20 percent of building inside that they can make revenue from in exchange for providing that. They have removed it. In my opinion, they should pay rent to the city because they have removed that space. I’ll tell you what will happen. Very quickly, they will either remove the planters and bollards or they will identify what the security problem really is and will pay for it. If you are going to pay bonuses for privately-owned allegedly-public open space you have to do it very cleverly because what you get is leftover space. We have over 80 acres of privately-owned public space in the most expensive areas of New York City. Eighty acres is a lot of land. Much of it is dreadful. Some of it is wonderful.

AA: Houston famously is a city without zoning, although we have found ways of having quasi-zoning in various forms.

AG: You have all kinds of regulations.

AA: What is your feeling about zoning in Houston? Is zoning in Houston zoning by a different term? Would rigorous zoning provide for a different urban environment, possibly a better one?

AG: If you compare downtown Houston, downtown Dallas, and downtown Austin, I don’t think you will find that they look particularly different from one another. If anything, Houston has more quality architecture than the other two cities. I don’t think it has anything to do with the presence or absence of zoning. I think the arts areas of Houston are much richer and much livelier than in many other cities in the US. I’m a real believer in zoning. It is a wonderful way of obtaining, I don’t know how to describe it, a better city than you would get if there were no regulation. I’m all for it. But I think that we’ve gone too far from the real reason for zoning, which is to provide a great public realm. The zoning in New York in 1916 when it was passed, the buildings had height limits based on multiples of the street they were on. All of the regulations were focused on what kind of public realm you were going to get as a result of the area and height requirements. In 1961 when we moved to a Floor to Area Ratio, it all became a discussion of what people can do with their own property. I think that that switched in the wrong direction. There are some wonderful aspects of the 1961 ordinance. One of the bad things is that it eliminated a category. It went from a pyramid that began with residential only, then went to commercial and residential only, and half the city was unlimited. We have no unlimited category any longer. We would call that mixed-use today. It’s the politically correct thing today. If you said “unlimited” people would be horrified.

Yes, I think Houston would be an even better city with zoning, but I would be very careful about how you wrote a zoning resolution that would actually improve things.

AA: Speaking of zoning, I understand that you give a zoning performance to your students?

AG: Every year when I teach zoning, it’s a two-hour lecture. I play three caricatures. The first is a New Yorker, who comes in with a long tie and a NYPD cap, and explains how zoning is the right way to plan cities. He presents some ridiculous ideas and some very profound ones about why you would want to regulate the use of property. I stop. I remove my jacket. I remove my tie. I put on a cowboy hat and I become a Houstonian. I argue zoning is unconstitutional. It also has some profound comments and ridiculous non-sequitors. I take off my cowboy hat and put on a bow-tie because that’s what Garvin would be wearing. I put on another jacket and proceed to comment on what the other two said, also with some ridiculous non-sequiturs and some very profound comments. I think that the conversation about zoning is not particularly profound most of the time. It’s slogans. The people who oppose zoning have good reasons. The people who are for it have good reasons.

AA: Are you hopeful about urbanization in cities?

AG: Absolutely. If Paris can do this for a place which now provides for demonstrations over Charlie Hebdo and everything else, and Houston can do it by putting a bus lane down the middle of Post Oak, and Dallas can cover up a highway, of course I am hopeful. These are very different cities doing wonderful things.

AA: We’ve seen a lot of hopeful urbanism, we’ve seen great transformation over the past decade. Where do you see the challenges of the next decade? Where would you focus the attention of urbanists and planners?

AG: Number one is to improve the existing public realm and make it more useable for everybody. The second thing I would say is provide a dramatic increase in the supply of housing so the overall price drops everywhere and appropriate money to provide housing for persons of low income. Remember I’m the former deputy housing commissioner of the housing authority of New York. We had a simple thing we did that I was involved with which was to provide a tax incentive if you fixed up your building. In 1955 the city passed a law called J51, you can read about it in The American City in several places, they said we will not increase your assessment because of improvements for a period of twelve years. To the degree that you are improving quality by providing new windows or plumbing or bathrooms, you can deduct 90 percent of the cost of the improvements from your tax bill for a period of 20 years up to 90 percent of the value of the investment. We had levels for what you could do for bathtubs, what wiring costs. I administered that law. I think there is a lot we can do with the existing housing stock, and that’s where we ought to be looking. Convert garages into apartments, convert basements into apartments. That’s the quickest, fastest, cheapest way to provide housing for people. And new construction. I’m for that too, but that’s different.