Margaret Guroff's new book, The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life, will be published this month by the University of Texas Press. The book, according to the press, "reveals how the bicycle has transformed American society, from making us mobile to empowering people in all avenues of life." To read more about bicycling on OffCite, including Raj Mankad's analysis of the new Houston Bike Plan, click here.

Allyn West: The Mechanical Horse demonstrates what you call this county’s “on-again, off-again romance” with the bicycle, starting with the first exhibition in 1819 of a “draisine." Then the bicycle was dismissed as a fad and disappeared, only to reemerge in new forms throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ultimately, you argue that, just a generation after bike use fell off in the late 1960s to where 85 percent of bikes were ridden by children only, the U.S. is again in the midst of a “dewy-eyed affair.” You point to the rise of bike-share programs and a surge in bike commuting among urban adults. What else accounts for this resurgence of interest?

Guroff: After decades when U.S. cities were losing population, they've begun to grow, and that population density puts more Americans closer to their jobs, shopping, and schools. That makes commuting and doing errands by bike more realistic for those who want the exercise or who don't want to deal with traffic jams or parking hassles. A drop in urban crime is also a factor --- you're more likely to ride a bike if you're not seriously concerned about having it stolen, or about being mugged. Those crimes still happen, of course, but they're statistically less frequent than they were a decade or two ago, and that makes people more comfortable being out and exposed on a bike.

City planners know that getting more people on bikes reduces air pollution, gridlock, demand for parking, and wear and tear on asphalt, so city and regional governments have begun creating safer spaces for people to ride, including cycle tracks protected by curbs or parked cars. And the safer cycling gets, the more people ride ... and the more cyclists there are, the more lobbying they do for still more bike lanes.

But this is very much a phenomenon of prosperous city-dwellers. There are still lots of places in the country where it doesn't make sense to ride bikes for transportation, because the infrastructure is built to exclude them or because people can't live within cycling distance of where they work, shop, study, or worship.

West: You argue that a the bicycle has been a “catalyst for unimaginable social change” and point out that it was, notably, an early vehicle of feminism, for example, allowing women to pedal away from constraints on their personal mobility. (The design of the bike even accommodated the bulky dresses social norms required.) Does the bicycle still play the role of a catalyst for social change? What social change might the bicycle now be a part of?

Guroff: In the U.S., I don't see the bike acting right now as a spur for the sort of sweeping social change that it helped foster in the late nineteenth century, when it was a radical new technology. It freed women from some pretty oppressive expectations about their behavior, and it also contributed to big changes in the way people thought about their health, among other things. But certainly there are groups working now to enact change and empower people through cycling. In New York, there's a nonprofit called Recycle-a-Bicycle that teaches kids to refurbish bikes while they learn about healthy living and protecting the environment --- and then they can use the bikes to get around. The United Nations Foundation has a program called SchoolCycle that donates bikes to girls in Africa and South America so they can reach their distant schools and don't have to drop out. The bike still has the potential to be a life-changing technology.

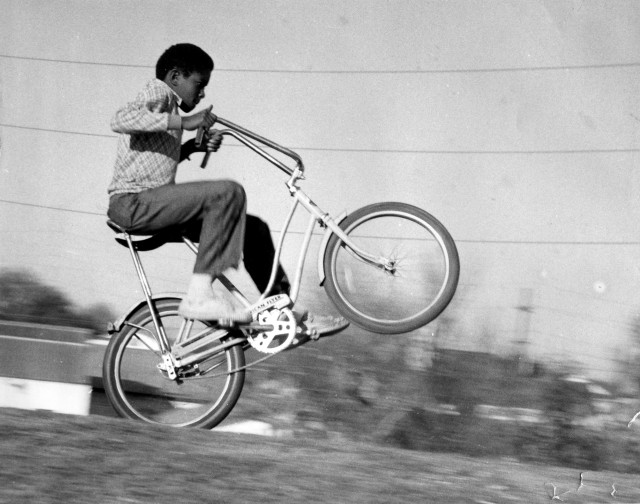

Phil Leon captured this image of a New Orleans or Texas neighbor performing a wheelie sometime in the 1970s. Photo: Kumar McMillan under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

Phil Leon captured this image of a New Orleans or Texas neighbor performing a wheelie sometime in the 1970s. Photo: Kumar McMillan under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

West: You also argue that cities are "the natural habitat” for bicycles. Can you elaborate on that point? And is that true only for dense, antique cities like New York and Washington, D.C., where you’re based, or for sprawling Sun Belt cities like Houston, as well?

Guroff: Cities are defined by density; they tend to be places where homes and jobs and schools and shops are close enough together to be reachable by bike. Also, stop-and-go urban traffic is slower than on suburban loops and collector roads, which makes it more a cyclist's speed. In a newer city like Houston, the distances might be greater than in the oldest parts of Boston, for example, but you may still find that some of your daily destinations are reachable by bike from home. Or it might be more of a multimodal thing, where you drive to a job in the central business district but then take a B-cycle to a midday meeting.

West: New roads are often built, at least in Houston, to move cars as efficiently as possible. Do we need a new kind of road for bicycles? Is it possible — and what might make it so --- for cars and bicycles to share the road?

Guroff: This is above my pay grade, as they say, since I'm not an urban planner, but you can look at places like Amsterdam and Copenhagen for examples of the kinds of infrastructure that move bikes and cars through a city in harmony. They have some roads just for bicycles, but also on-road bike lanes, and intersections designed to make cyclists and pedestrians more visible to drivers and help them clear the crossings faster. These are called "protected intersections," and they're being tried right now in at least four U.S. cities, including Austin. I do think it's possible for cars and bicycles to share the road, but the roads need to be built with that in mind.

West: As a cyclist, you must understand deeply the experience of riding in a city. What do you get out of bicycling in a city? And what about the experience might recommend it to others who have never tried bike commuting?

Guroff: The main thing I get out of bicycling is efficiency. If it weren't the fastest way to get around my town, I wouldn't do it nearly as often. It's also great cardiovascular exercise, which saves me yet more time, since I don't have to go to the gym for that. It's incredibly cheap compared to driving or even public transportation. And it is so much fun! That sensation of zooming and balancing just makes you feel invincible. Or it does me, anyway. By the time I get to work I feel like I'm ready for anything.

West: “The Mechanical Horse” begins with an anecdote of hostility between a cyclist and a motorist. Even though, as you argue, the bicycle was here first, and bicycles, you write, “made cars feasible,” as bicyclists advocated for better roads in the late 1800s. Still, this hostility between bicycle and car will be familiar to anyone who’s ridden in a city. What explains this hostility?

Guroff: I think it comes down to mindset. Driving in heavy traffic is a really annoying experience, so of course many drivers feel irritated and on edge. You're blocked in, you're late, you're bored. And you can't really get mad at the other drivers in the jam, because they're just doing what you're doing.

Meanwhile, the cyclists on the road are having a completely different experience: they're not trapped, they're not late, they're just zazzing along and feeling a bit of Schadenfreude towards the drivers stuck in traffic. And they're on high alert --- or they ought to be --- because any car door can open at any time, or any vehicle can veer into them, and they could literally die. When you're riding in traffic you feel exhilarated --- the exact opposite of bored.

So there are these two opposing states of mind interacting, and when they both want the same patch of asphalt, tempers can flare pretty quickly. But when there's no traffic it's a different story. I sometimes ride in the city very early in the morning or very late at night, and drivers just leave the right lane to me and pass in the left. No one ever yells at that hour --- there's nothing to yell about.