Melanie Ford is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at Rice University where she is also a co-coordinator of the Ethnography Studio and fellow at the Center for Energy and Environmental Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities (CENHS).

Guatemalan architects tell me that the lungs, los pulmones, of Guatemala City are ravines, living and breathing, part and parcel of the urban life of la ciudad. Indeed, from a bird’s eye view, the ravines themselves evoke the arterial network of lungs, stretching far out into the city center and deep into the volcanic foundations of the country. Yet, if the ravines are the lungs of Guatemala City, architects tell me that there is cause for concern. At one scale, ravines, or los barrancos, are sites of Guatemala City’s most pressing environmental issues. Out of sight and out of mind, the ravine depths are landscapes once sculpted by water but now shaped by landfills and sewage infrastructures. At another scale, ravines host much of Guatemala City’s urban poor. After the thirty-year civil war and genocide, many sought refuge under ravine foliage, informally building communities that continue to grow more permanent each passing day.

Informal settlement known as “La Limonada” in a ravine of Guatemala City. It is estimated that at least 60,000 people reside here. Photo by author.

Informal settlement known as “La Limonada” in a ravine of Guatemala City. It is estimated that at least 60,000 people reside here. Photo by author.

The Guatemala City garbage dump, among the largest landfills in Latin America, located in a city ravine. Photo by author.

The Guatemala City garbage dump, among the largest landfills in Latin America, located in a city ravine. Photo by author.

In 2010, however, a local group of architects turned their attention to these ravines, alluding to them, on the one hand, as spaces of waste and, on the other, as wasted spaces. Architects I spoke with argued that rapid urban growth and the absence of action to properly plan for the influx of residents, and their subsequent use of resources, has led to a disconnect between Guatemala City residents and their surrounding natural environment. In what they have described as a grassroots movement, these architects have taken it upon themselves to research and argue why ravines are important sites for conservation and how to best do so. In a 2014 report from the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala architecture school coordinated by Jaurez Monterosso, they argued that a ravine’s vertical form further segregates communication and exchange between socioeconomic classes --- a physical and literal hierarchy --- and the lack of care to conserve ravine ecologies has led to an unorganized and contaminated city. Though more akin to Toronto’s deep ravines in depth, the Guatemala City ravines have some of the same opportunities and challenges around inequality that have been identified as part of Houston's Bayou Greenways initiative. The ravines are sites that deeply bind social experience and city development. To design the ravines is to curate and maintain a cultural inheritance that these architects view as fundamental to designing a Guatemala City more socially and materially equitable and interconnected. In what follows, I detail a small portion of my summer with these architects who seek to slowly transform Guatemala City’s ravines into sites that inspire a sustainable consciousness in city residents and rekindle a vanished and local identity.

History

While there is no written history specifically about ravines and their active relationship in the bounding and building of Guatemala City, traces of historical scholarship showcase ravines as actors in the making of a Guatemalan identity since colonial rule. In 1773, Guatemala remained an audiencia, or capital site, under the Spanish king. At this time, the capital of the region was located just west of Guatemala City in a town currently known as Antigua. Over the course of several decades, Antigua would be devastated by earthquakes and rebuilt time and time again (Martínez Paláez 2009). However, in 1776 by command of the Spanish King, and after a particularly devastating set of earthquakes in 1774, Charles III of Spain ordered the capital moved to a region that would be safe from territorial threats, noting that the ravines of Guatemala City were forms that could protect the city from foreign enemies and were sites unlikely to be devastated by earthquakes or volcanic eruptions (Muir-Wood 2016). This would eventually prove to be false, but the concentration of Guatemala City in the small area enclosed by ravines ultimately became the city’s informal boundaries. After gaining independence in 1821, the capital of the country remained in Guatemala City growing outward and sporadically on ravine plateaus.

However, ravines were not just environmental forms that bounded the city to certain spaces for urbanization, but their depths were also sites of refuge for Guatemalans who were fleeing the rural countryside during the country’s civil war and genocide. A series of military dictators, stringent land reforms, and the eradication of rights of Maya and ladino peasants, forced an influx of the Guatemalan population to migrate to the capital city in search of stability (Grandin 2000). With no room to house the amount of people above on ravine plateaus, ravine depths became sites of hiding and concealment for both those fleeing violence and for those who had succumbed to it (Low 1988; Saunders-Hastings 2018). By 1996, the year of the official end to the civil war, ravine lands had been privatized by wealthy land owners or appropriated by an unstoppable force of informal settlements, rarely to be formally discussed at any municipal level until the late 2000s.

In the early 2010s, an independent group of architects banded together to create the initiative Barranco Invertido, literally meaning inverted ravine. Barranco Invertido became a working theory group, delivering a “No Manifesto” listing what ravines are not, and what ravines could be (Ciudad/Barranco 2015). Rather than advocating for typical conservation efforts, publications and research produced by Barranco Invertido have called for radical and sustainable redesign of Guatemala City’s urban future through individualizing and accessing the infrastructural, recreational, and developmental potential that each ravine possesses (Monterosso Juarez, et. al 2014). While some architects spoke to me of their imaginations for floating houses, or bridges that cross ravine’s great divides, an ecological park named Jungla Urbana (Urban Jungle) was the first project to be realized in any ravine. Their inspiration was to rekindle the once local pastime of barranquear.

Los Barrancos Nos Unen

The group Barranco Invertido defines barranquear as an “action verb that signifies the act of exploring and the spontaneous appropriation of residual space within ravines.” Ravines are not just abundant in Guatemala City, making up 42 percent of the city terrain, but, as I have argued, locate much of the city’s identity. When I spoke with architects regarding their reasoning to mobilize barranquear as the driving force for their designs, rather than say solely conserving ecological diversity, they spoke fondly to me of a pastime they remembered as children. For them, ravines were lush sites of unknowns, filled with greenery and adventure, a landscape where one could hike and play, an escape from the bustling industrialization taking place above. Other citizens I spoke with also recalled their memories of barranquear. One man smiled as he reflected upon the satisfaction of drinking the natural and clear water that trickled through the green foliage after he grew tired from playing with his friends — a stark contrast to the brown and odorous water that now runs along ravine banks. But now, even if one wanted to enjoy the ravines in a similar fashion, save for the inability to drink their water, there are seldom spaces to do so. Refurbishing ravines as sites for barranquear is not just important to these architects but vital to reclaiming sites that contain an inherently Guatemalan value. In other words, the ability to barranquear once again for these architects was to regain a sense of residency in Guatemala City that could no longer be granted. The ravines join us, they say, los barrancos nos unen.

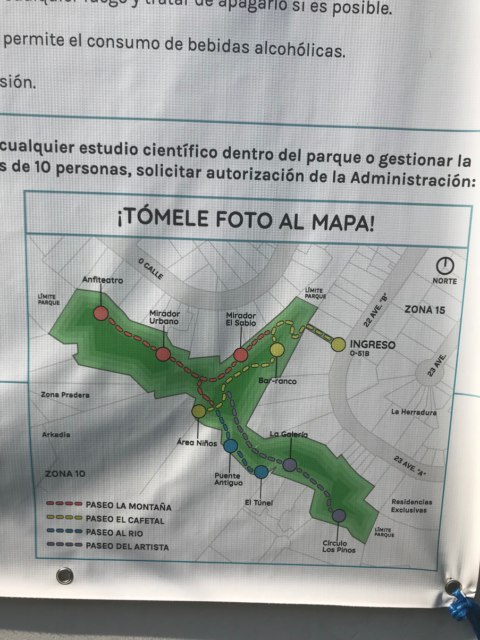

The first project of Barranco Invertido, Jungla Urbana, is now owned by the city municipality and nestled in a narrow ravine in a middle-class neighborhood of Guatemala City. A small door, separating two homes, opens to the public every day. While its entrance could be missed if not actively looked for, guarded and greeted by one municipal worker, Jungla Urbana avails itself to anyone curious enough to venture within the ravines. Signs demarcate paths for visitors to follow, but the vast greenery of the ravine supports exploration in order to instill one’s own relationship to barranquear. While there are landmarks within the park, such as a mural with local art and a stage for community gatherings, marked paths resemble natural desire lines that give a sensorial experience, evoking the history of ravines and offering imaginations of others who might have previously roamed the space.

Entrance to Jungla Urbana. Photo by author.

Entrance to Jungla Urbana. Photo by author.

Among many other landmarks and uses of the park, barranquear is designed into Jungla Urbana through the intentional arrangement of trodden paths and the remnants of construction and rubble from the ravine’s past. Alluding to cultural heritage becomes a method of conservation that, on the one hand, inspires a sustainable consciousness and support for sustainable city design, and, on the other hand, foregrounds ravines as specific ecological forms that offer possibilities of a coalition unique to Guatemala City’s locale. Architects offer ravines not only as ecological sites that should be engaged for the betterment of residents in Guatemala City (as the city’s lungs), but as an opportunity to inspire an appreciation of environmental forms that are uniquely Guatemalan (the hopeful recovery of barranquear).

Photos of Jungla Urbana by author.

Photos of Jungla Urbana by author.How do architects and their design of ravines work to curate a connection and unification amongst Guatemala City residents? How is design deeply entwined with the conservation of memory — historically, materially, and sensorially — of ravines as social actors in the making of a Guatemalan City identity? While the architects of Barranco Invertido and their project Jungla Urbana are efforts to conserve and care for the ravines as ecological sites in and of themselves, they are just as much an effort to conserve or reignite a piece of Guatemalan heritage, a shared space and proposition for coalition.

This work is part of the author’s ongoing dissertation research; any and all mistakes are entirely her own. The author would like to thank all the members of Guatemala City’s municipality, Barranco Invertido, Fundación Crecer, and everyone in between who took their time to graciously explain, invite, and inform her ongoing dissertation research. Melanie Ford is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at Rice University. Fascinated by the nexus of design and ecology, her research focuses on interventions in the ravines (los barrancos) that compose almost half of Guatemala City’s terrain. She is interested in how ravines — their vertical and negative forms — are spaces of and for collaboration in Guatemala City’s urbanized and ecologically-minded future. Her research adds to existing scholarship on class, democracy, public space, property, and security in postwar and peacetime Guatemala. At Rice she is also a co-coordinator of the Ethnography Studio and fellow at the Center for Energy and Environmental Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities (CENHS).

Works Cited

Grandin, Greg. The Blood of Guatemala: A History of Race and Ntion. Duke University Press, 2000.

Low, Setha M. “Housing, Organization, and Social Change: A Comparison of Programs for Urban Reconstruction in Guatemala.” Human Organization 47, no. 1 (1988): 15–24.

Monterroso Juarez, Raul Estuardo, et. al. “Ciudad/Barranco: Análisis estratégico de potencialidad y economía territorial de los barrancos del Municipio de Guatemala como herramienta para la sostenibilidad en los asentamientos humanos.” Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, 2014.

Muir-Wood, Robert. The Cure for Catastrophe: How We Can Stop Manufacturing Natural Disasters. Basic Books, 2016.

Nelson, Diane M. A Finger in the Wound: Body Politics in Quincentennial Guatemala. Duke University Press, 1999.

O'Neill, Kevin Lewis, and Kedron Thomas, eds. Securing the city: Neoliberalism, space, and insecurity in postwar Guatemala. Duke University Press, 2011.

Peláez, Severo Martínez. La Patria del Criollo: An Interpretation of Colonial Guatemala. Duke University Press, 2009.

Weld, Kirsten. Paper Cadavers: The Archives of Dictatorship in Guatemala. Duke University Press, 2014.