With 15,000 homes on 4,000 acres built by Frank Sharp beginning in the 1950s, the Sharpstown neighborhood was at one time among the nation’s largest communities of single-family homes. The streets were lined with midcentury designs fitting of the era, with one-story sloping roofs and brick exteriors. As Randal Hall and Steven Thomson have written for Cite, the neighborhood transformed after the 1982 economic downturn from a White suburb to immigrant-rich density. Despite maintaining a mix of predominantly moderate-income families, the perception of Sharpstown has waned. The developer Seeds of Sharpstown has begun shifting that perception in recent years and the recently announced Sharpstown Prize for Architecture is its latest effort.

Founded in 2011 by Mike Prentice, Seeds of Sharpstown has developed roughly 70 residential properties in the area, including rental and resale. (A few have become art installations along the way, including “Remnants of the Past, Visions of the Future” and “Sharp.”)

Working in concert with the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design, Sharpstown Prize for Architecture competition requirements were set by Seeds of Sharpstown to reflect the needs of the neighborhood – single-family residence, between 1,000 to 1,200 square feet, three bedrooms and two bathrooms, no more than two stories in height. The most challenging of these requirements was the $140,000 construction budget.

Professor Rafael Longoria’s graduate level studio consisted of 10 students who approached the design problem by developing different solutions through different schemes – courtyards, shifting volumes, and two stories. The students interviewed nearly 60 current residents throughout the design process for their input and feedback. Pat Menville, president of the Sharpstown civic association at the time of the competition, said that the students “talked to countless residents of all ages and stages” and ultimately brought architecture to life “not just as a construct – but as a living space.”

Site plan and floor plan. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

Site plan and floor plan. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

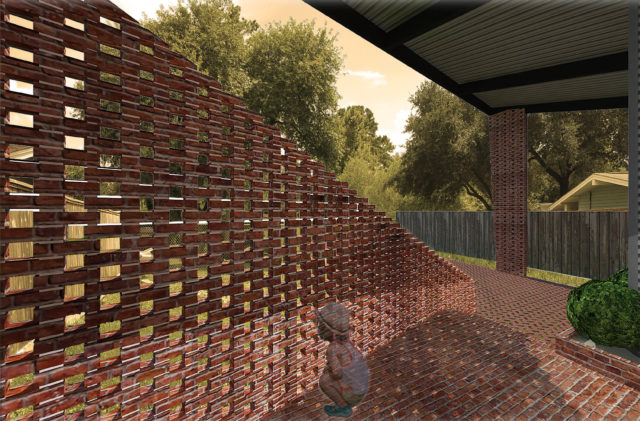

View from patio. Courtesy of Tanmay Thankker.

View from patio. Courtesy of Tanmay Thankker.

View from backyard. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

View from backyard. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

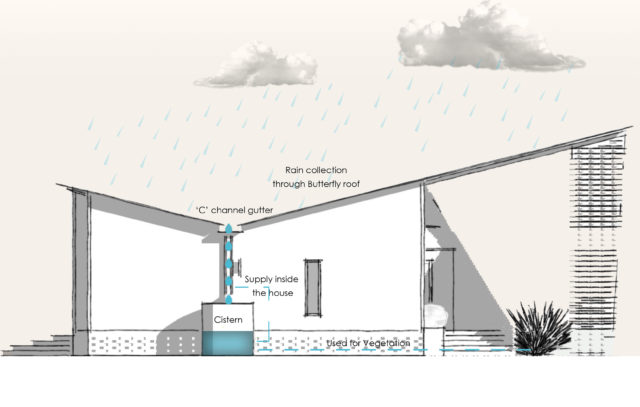

Rain Diagram. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

Rain Diagram. Courtesy of Tanmay Thakker.

Michael Prentice and David Robinson. Courtesy of Seeds of Sharpstown.

Michael Prentice and David Robinson. Courtesy of Seeds of Sharpstown.

The winning design by Tanmay Thakker blends contemporary amenities and approaches with midcentury features typical of the neighborhood. Set back roughly 50 feet from the property line, Thakker’s design matches the building line established by the neighboring homes. The front entrance is further set back from the street, under a slanted extension of the covered carport and behind a slanted brick rain screen that, together, form a somewhat exaggerated play on the “Sharp” art installation in Sharpstown. Approximately 90 percent of the predominantly midcentury buildings in Sharpstown have brick exteriors, on which brick rain screens are common. Thakker modernized the decades-old concept by integrating a gradient in the perforation of the brick – the perforated gradient skews closed as one nears the front door entrance.

Directly to the side of the front door entrance is the main living core. Living, dining, and kitchen are organized in a modern (sans midcentury) open floor plan. Midcentury floor plans, in contrast, have more compartmentalized programming, with clear walls to define the breaks in space. By breaking down the proverbial walls, Thakker’s design results in a more open, lit living core.

The floor plan is U-shaped, centered around a covered courtyard. The main living core forms the bottom half of the U, bridging the bedroom wings. The west wing incorporates two bedrooms that share a full bathroom with the main living core. The east wing contains the master bedroom suite, with a private bathroom and closet. Thakker blends midcentury cross ventilation strategies with the U-shaped floor plan. Each perimeter wall that opens onto the covered courtyard features a screen door and large windows, which can be used not only for ventilation but also to bring natural light into each wing of the home.

Professor Longoria described his student’s design as an update to “the ranch houses originally built in that neighborhood, accommodating current flooding concerns and energy-saving innovations.” With the property in the 500-year floodplain, Thakker raised the finished floor level to meet city requirements and covered the crawlspace with a perforated brick design. Apart from the brick on the crawlspace and on the front façade, the rest of the home’s exterior walls feature energy-saving metal siding. In addition to these material selections, energy-saving techniques are implemented in both the roof design and utility procurement. The butterfly roof design is designed to channel sloping rainwater into two rain barrels located on both the western and eastern walls, which can then be filtered and used within the home. South-facing solar panels on the roof connect to a battery pack and inverter that translates solar energy into electricity the homeowners can use.

Thakker is working with Seeds of Sharpstown in the next step of finalizing construction documents for permitting with the City of Houston. Following permitting, they will start construction in the coming months.

David Robinson, City Councilman At-Large, alluded to the vision of the Sharpstown Prize of Architecture translating to a citywide stage with the planned “Houston 2020 Visions” program. Five lots have been pre-selected per each of Mayor Turner’s Complete Communities in Acres Home, Second Ward, Near Northside, Gulfton, and Third Ward. Working with AIA Houston and with the support of Mayor Sylvester Turner, the program will be issuing a Request For Visions (RFV) to encourage submittals like those realized by Professor Longoria’s students during the Sharpstown Prize for Architecture competition. The program will be initiated on the second anniversary of Harvey this coming August.

Texas State representative Gene Wu lent his support to initiatives like Sharpstown Prize for Architecture, saying that “moderate-income neighborhoods still need good architecture.” The Sharpstown Prize for Architecture sets precedent of the public sector and the private sector working together to create community centric and responsive architecture as Houston meets Mayor Turner’s call and Houston’s need of creating complete communities.

Cheryl Joseph is an architectural designer at Titan Homes in Houston.