This planning series is written by NuNu Chang, co-owner and principal of Albers Chang Architects in Houston. She serves on the editorial committee of Cite.

Almost two decades ago, in 1999, the city of Houston adopted a radical set of development standards to densify housing stock within the 610 Loop. The changes would be twofold: 1) by reducing the minimum lot size from 5,000 square feet to 1,400 square feet, redevelopment of existing lots into much smaller lots would be allowed, and 2) when permission would be needed to redevelop such a property, it would be easily granted. The conspicuous result of these sweeping changes would be the rapid replacement of one-and two-story houses within the 610 Loop with three-, four-, and now five-story townhouses.

But which properties would be selected for redevelopment? Would they be lots containing condemned structures or those along transit corridors adjacent to commercial buildings? If the city’s development goal was to increase housing units per acre, would multi-family units be incentivized, or at minimum, be protected from replacement with single-family units?

Rather, the vast majority of housing stock to be replaced would be those in neighborhoods with good proximity to transit and amenities but lack deed restrictions or historical protections. Houses, and paradoxically duplexes and fourplexes would be replaced in piecemeal fashion as they became available — at times an entire block would be redeveloped as townhouses, but more often, on one or both sides of a house.

As estimated by Carson Lucarelli, a planner at the planning department, the city now processes 200 to 250 plats and replats per month, of which replats compose approximately 15 to 30 percent of the applications. To consider the impact of these policy changes, we can apply the lessons learned from neighborhoods within the 610 Loop that underwent a rapid rate of redevelopment in the past two decades to those neighborhoods exhibiting a similar pattern of development today. Outside the 610 Loop, redevelopment was similarly opened in 2007.

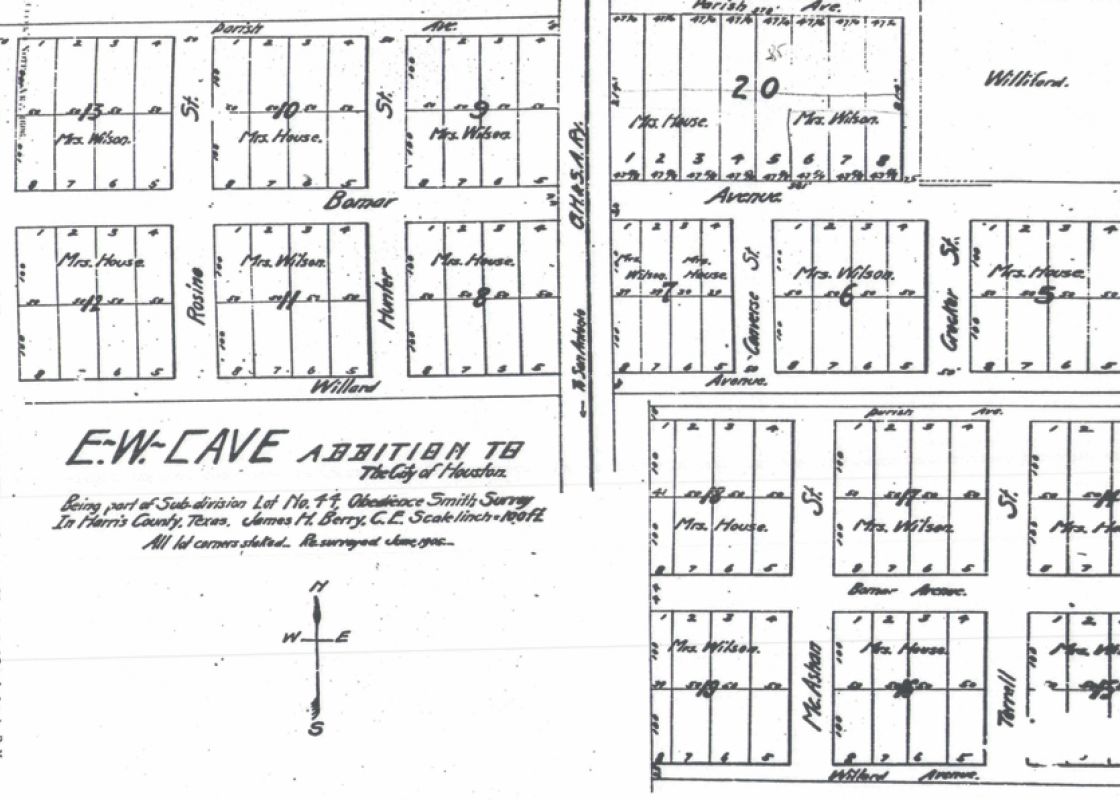

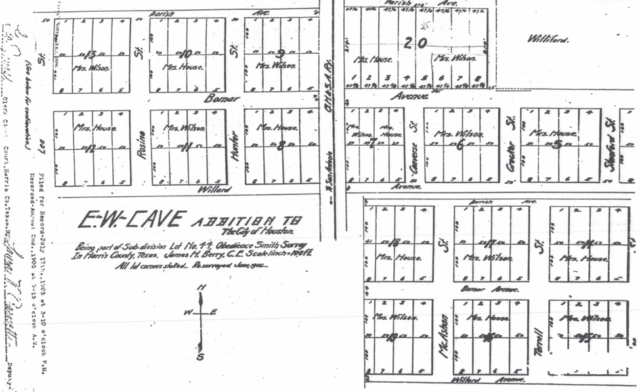

E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose. Photograph by NuNu Chang.

E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose. Photograph by NuNu Chang.

East Montrose presents such a case study. Approximately .3 miles west-east and .5 miles north-south, this section of the larger Montrose area is hailed for its walkability and proximity to restaurants, excellent public and private schools, and Buffalo Bayou Park. For residents, East Montrose has even greater appeal than a neighborhood modeled on the winding picturesque streets of the City Beautiful movement, in which the nearest grocery store or school may not be within walking distance. The 200-foot by 200-foot block size would likely have been planned for walkability, a feature shared by downtown Portland, Oregon. Walkability is stated to be a top priority for the city and mayor Turner, according to the planning department webpages.

For a developer, most of East Montrose lacks both deed restrictions and historical protection and its standard lot size is optimal for replatting for townhouses. Within a one- to three-month planning review process, a 50-foot-by-100-foot mid-block lot can be subdivided for two townhouses, and a corner lot subdivided for three townhouses. [1]

From the city’s plat maps, East Montrose is today composed of roughly 340 townhouse units, 230 houses, and 15 multi-family properties. Townhouses outnumber houses 1.5 to 1. Today, only six of the 80 blocks in East Montrose remain as platted in 1906 for eight houses per block.

The particular section of East Montrose where I live is a subdivision called E.W. Cave, bequeathed to his two surviving daughters by Eber Worthington Cave. An influential publisher from Philadelphia, Cave would eventually serve as secretary of state under Sam Houston. Like other titans of industry of his time, Cave was involved in rail and shipping, eventually as director of the Houston and Texas Central Railway. Most remarkably for the post-industrial development of Houston, Cave envisioned the possibility that by connecting Houston’s Buffalo Bayou to the Galveston ship channel, it could become a viable port.

Driveway for townhouses in E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose. Photograph by Raj Mankad.

Driveway for townhouses in E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose. Photograph by Raj Mankad.

"Shall Approve": Replats Made Easy

Houston’s distinct lack of formal zoning for land use, such as to designate areas for single-family, multi-family, commercial, or industrial, was born of intense opposition of the Houston Property Owners League to the city’s initial zoning proposal made in 1929. The coded zoning ideals of “health, safety, morals or general welfare of the community,” common to progressive City Beautiful planning of the 1920s was declared by opponents to be elitist and “an abrupt departure from individualism.” (For more history, read The Hogg Family and Houston: Philanthropy and the Civic Ideal by Kate Sayen Kirkland and "Planning in Houston" by Stephen Fox.)

The four-member planning commission of 1929, then an informal advisory board, was itself divided on the issue of zoning. The expiration of deed restrictions in Montrose in 1937 hastened the reorganizing of the planning commission in an effort to reopen the possibility of zoning. From 1929 to 1993, referendums for zoning would fail four more times. It is now nearly 90 years after Houston first embarked on the path of unhampered growth over civic and environmental concerns. These are the issues around which the Rice Design Alliance, publisher of Cite, was formed in 1972.

In lieu of formal zoning or planning, neighborhood-based deed restrictions can limit a property to certain land uses. They may also define building setback lines, maximum building height, lot size and the number and orientation of structures per lot. Often, the deed restrictions are more stringent than Houston’s development ordinances for maximum building height and setback, and form the governing restrictions for a project. Not unique to Houston, deed restrictions throughout the US were drawn up in the 1940s and 50s, with racial segregation among the motivations.

For residents in many Houston neighborhoods, deed restrictions do not exist and the extent that the restrictions are enforced depends on the level of involvement of the homeowners’ association or civic club and the residents themselves. The burden of responsibility to comply with the deed restrictions is largely on the owner — when submitting for a building permit, the city requires a declaration to be signed by the owner, indicating that “The Project does not violate the Deed Restrictions, if any, that apply to the Land.”

As I documented in Planning the Houston Way: Part 1, the deed restrictions governing Southgate Section 3 was the neighborhood’s first defense against the development of townhouses in a neighborhood of almost exclusively single-family houses. In such a deed restricted neighborhood, additional steps must be taken by the developer in order to obtain a hearing for a property to be replatted for redevelopment. These requirements coupled with an active civic club and well-informed residents, often but not always, present a formidable impediment to incompatible redevelopment.

Conversely, the rapid rate of redevelopment in East Montrose, a neighborhood largely without deed restrictions, is aided not only by city ordinances but by state law. Under Texas state law 212, a public hearing for a replat is required only if the property has or had restrictions specifically limiting the use to single-family, even if the additional lots created are also single-family. But, if the deed restrictions do not limit the property to single-family and the replat complies with the deed restrictions and the development ordinances, the planning commission must approve the replat. These items are identified in the planning commission hearing minutes as “Shall Approve.”

Plat drawing for E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose, recorded in 1906. The 1906 plat created 200-foot-by-200-foot blocks, each containing eight 50-foot-by-100-foot single-family lots.

Plat drawing for E.W. Cave, a subdivision of East Montrose, recorded in 1906. The 1906 plat created 200-foot-by-200-foot blocks, each containing eight 50-foot-by-100-foot single-family lots.

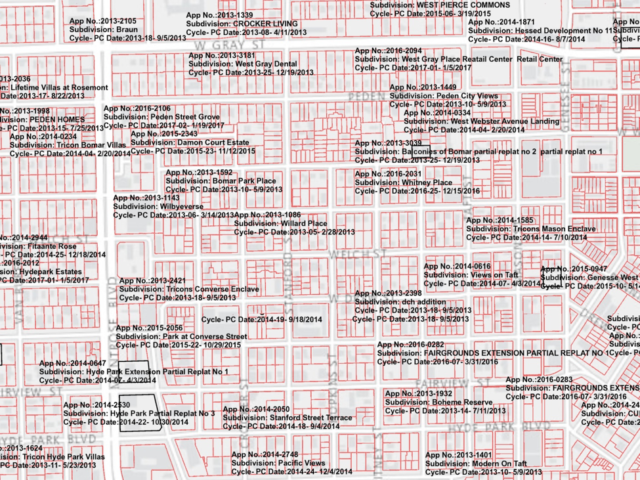

2017 cadastral of East Montrose, showing the subdivisions created with each replat for townhouses. http://mycity.houstontx.gov/houstonmapviewer/

2017 cadastral of East Montrose, showing the subdivisions created with each replat for townhouses. http://mycity.houstontx.gov/houstonmapviewer/

The frequency of “Shall Approve” items and their expedient approval at the planning commission hearings would indicate that a replat case marked “Shall Approve” is all but won, pending city council approval. For residents concerned with preserving the character of their neighborhood, it is crucial to avoid this classification. And, since 2001, residents have had such an option to prevent incompatible development.

Shortly after the 1999 changes to the development ordinances, a new legislation in 2001 allowed Houston residents to curtail incompatible development in their neighborhood on a per-block basis, using the Special Minimum Lot Size by Block (SMLSB) designation. The SMLSB application would establish a new minimum lot size for the lots on the block, calculated to prevent the subdivision (or replatting) of lots to be smaller than the prevalent lot size. If the lots on a particular block application were all already 5,000 square feet, the SMLSB would be 5,000 square feet, preventing any lots on the block application from being replatted to, for example, two 2,500-square-foot lots.

To clarify these terms, special minimum lot size (SMLS) can be obtained by residents by block (SMLSB) or by area (SMLSA). Similarly, a special minimum building line by block (SMBLB) [2] can be obtained by residents, typically to preserve their prevailing building line. Most of this installment refers to SMLSB — because it is submitted by block, rather than by area, it is significantly faster to obtain than SMLSA.

Planners such as Abraham Zorrilla, of the community sustainability division of the planning department, facilitate these applications on behalf of residents. While the interpretation of a set of deed restrictions could be challenged, SMLS establishes a new lot size calculated at a size to prevent replats in the application block or area and restricts the application block or area to single-family use for up to 40 years.

Parsing out Profit Margins and Other Motivations

Despite having had the SMLSB option since 2001, why would residents of East Montrose have only made a total of six applications, all in 2016 and 2017? In recent years, its residents have enjoyed some benefits of increased density, such as new commercial amenities and the replacement of some dilapidated structures.

Of the East Montrose residents who opposed SMLSB, the objection I came across more frequently than any other was that a developer would offer more, in cash, for a property than would a new homeowner. Cheryl Joseph, an architectural designer at Titan Homes familiar with the real estate market inside the 610 Loop, explains that there is in fact a purchase price of $90 to $100 per square above which a townhouse developer would not likely top.

The profit margin on a development is tied primarily to construction cost and the price of land. On a 3,400 square foot townhouse unit, a developer could expect to be profitable at a land cost of $40 to $50 per square foot. The same 3,400 square foot townhouse would no longer be profitable at a land cost of $90 — $100 per square foot. Here’s why:

Lot values in East Montrose have more than doubled from $40 per square foot in 2007 to $100 per square foot in 2018 — it now costs a developer $250,000 compared to $100,000 to purchase 2,500 square feet of land on which to build one townhouse unit. Townhouses in East Montrose built in the last two years have commonly sold for $750,000 to $775,000 for 3,400 square feet of livable area. Deducting the cost of the land, the sales price of only the structure is $525,000 or $154 per square foot. To compare, if one were to commission a house to be built in Montrose, the typical average cost of construction ranges from $150 to $200 per square foot.

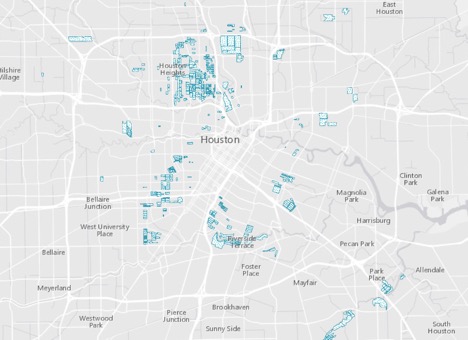

The map above shows the distribution of SMLS designations in the 610 Loop as of 2017. http://mycity.houstontx.gov/houstonmapviewer/

The map above shows the distribution of SMLS designations in the 610 Loop as of 2017. http://mycity.houstontx.gov/houstonmapviewer/

While sales price is of primary importance to a resident intending on moving out of the neighborhood or to a developer seeking profit, what of the majority of residents invested in their community? The wide range of concerns given by residents speaking in protest at replat hearings indicate underlying issues with the development approval process itself and a potential conflict with the city’s long-term development goals.

Four of six SMLSB applications in East Montrose were made largely in reaction to the development of four-story townhouses approved for replat on July 11, 2013. This is the site of the much-publicized illegal removal of a 100-year old live oak tree on the city’s right-of-way, for which the developer was ultimately assessed a fine of $125,000. Some residents objected to the incompatible height of these four-story structures, while others cited consistent ponding on the street post-development.

Limitations of Special Minimum Lot Size Protection

SMLS can prevent potentially onerous aspects of development, but SMLS is in fact not a sufficient tool to shape development. Perhaps the most frequent complaint related to incompatible development is the height of three-, four- and five-story townhouse structures dwarfing the adjacent one- or two-story house. While SMLS prevents the replatting of a property without which a townhouse would not likely be developed, SMLS has no effect on limiting the height of a structure. In the city of Houston, the maximum height limit for a structure built adjacent to a single-family is 75-feet to the topmost finish floor — therefore no special exceptions are needed to build a 65-foot tall, five-story townhouse, or, for that matter, a house.

SMLS should be more judiciously implemented than merely as a band-aid — it too has long-term impacts on our built environment. SMLS not only establishes a new minimum lot size for the block or area, but also restricts the properties to single-family use, for up to 40 years. This form of spot zoning is implemented not at the city level or even by neighborhood, but block by block. Even SMLS can be circumvented — a developer needs only to purchase a few adjoining lots to create a new subdivision, to be governed by its own rules, limited only to the city’s loose ordinances, which even then can be modified with a variance.

The rapid rate of townhouse development that occurred in East Montrose from 1999 is now occurring in Second Ward, Shady Acres and Magnolia Park, among many other neighborhoods. Will a unique character develop in each of these communities? How will Plan Houston objectives of transportation, walkability and affordability be addressed? What is the actual role of planning and the extent of related infrastructure improvements in these areas?

Throughout this series, we invite readers to share your experience, questions, recommendations and photos related to development in Houston. Next up will be Part III: Design by Default, Form and the City Development Code.

Endnotes:

[1] Replat Rules

A replat of a 50-foot wide lot results in two 25-foot wide lots to accommodate the city requirement of two off-street parking spaces for a single-family dwelling, with just enough room for a 3-foot-wide walkway to the front door. A now common housing type, a townhouse is often sited much closer to the street and the side and rear property lines than the adjacent house.

These looser setback requirements are found in sections of the ordinance referred to as Optional Performance Standards, (Sec. 42-153 and 42-157), which allow a 10-foot front building line for the primary structure, a 17-foot garage door or carport setback and a maximum height of 75-feet to the topmost floor finish. To build to the zero lot line of the side and rear property lines, a variance is not required but a written agreement must be obtained from adjacent property owners.

Developments that can accommodate a shared driveway can even more dramatically reduce the front building line, significantly impacting the public realm. A mid-block development with a shared driveway can have a front building line of five-feet. A corner lot development with a shared driveway can reduce the front building line down to zero-feet, on both intersecting streets.

[2] Special Minimum Lot Size by Block (SMLSB) Application Process

There are two types of Special Minimum Lot Size (SMLS) applications—by area and by block. The Special Minimum Building Line (SMBL) application as well as applications to rescind such existing designations follows a similar procedure. According to planning and development staff, the process to obtain approval by area can sometimes take several years. In contrast, application by block typically takes an average of two months from receipt of the application to the planning commission’s recommendation to city council.

To submit the SMLSB (by block) application, the application must contain at least one entire blockface or opposing blockfaces, 60 percent of the lots must already be developed for or restricted to single-family use and contain at least one lot that does not already have a minimum lot size established by deed restrictions. While the form states that 51 percent of the homeowners in the application, weighted by the area of their property, must sign the petition for the application to be submitted, the planning commission has in the past encouraged residents to submit with fewer than 51 percent signed. Applications with fewer than 51 percent signed can still be approved if few or no protests are received.

Once the application is completed with the signatures attached, the residents of properties included in the application are notified by mail and have 30 days thereafter to contact the city with questions or concerns, or submit a protest. You may have come across the NOTICE OF SPECIAL MINIMUM LOT SIZE BY BLOCK APPLICATION yard signs in neighborhoods from time to time. The contact information for the Planning & Development Department and hearing date are given on the sign and in the notification letters.

If there are no protests, the SMLSB application is approved by the planning commission without a hearing. If the application receives one or more protests, the application is scheduled for a hearing, which is open to the public including residents and speakers. Upon recommendation by the planning commission, the application would then be submitted to city council for approval and recordation.

For complete instructions to apply for SMLS (or building line), visit: http://www.houstontx.gov/planning/Min-Lot_Size-Min_Bldg_Line.html