This literature review of discussions in Cite since 1982 around Houston’s modern planning history begins by defining the terms and then moves through different phases — the gridiron, rail, and ports of the nineteenth century; open space planning in the 1920s; automobile-driven planning from the 1940s onwards; public transit masterplanning beginning in the 1970s; incremental planning from the 1980s onwards; and current and emerging practices. The survey ends with a set of case studies.

Most of the Cite stories on planning have this common refrain: Do not blame the hodge-podge development practices in Houston on a presumed lack of zoning but rather on the lack of comprehensive planning.

Understanding Planning

Zoning can refer to formal zoning that separates incompatible uses such as factories and houses, or form-based zoning (discussed in Cite Spring 2008 by David Crossley) that defines the shape of a structure. Zoning can also limit building heights, unit density, and setbacks. Zoning has also been the instrument of racial segregation in many cities. Comprehensive planning is a broader effort to align investments in transportation, utilities, recreation, and housing with community goals.

The Cite Fall 1991 issue focused exclusively on planning. Its foreword, “Through the Zoning Glass,” asserts that “zoning works best when it is used to support and implement a plan created by community consensus.” Archie Henderson's “Here’s Looking at Euclid” is a useful history of planning in the US with a discussion of zoning’s pitfalls and an optimistic look at how a zoning ordinance could both be inclusionary and entice businesses to improve quality of life. The piece includes an excellent reading list, “The Intrepid Reader’s Guide to Zoning.”

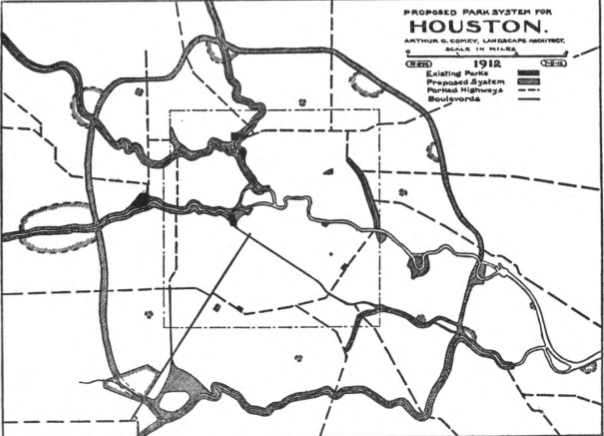

Plan for linear parks along bayous in 1912 plan by Arthur Comey.

Plan for linear parks along bayous in 1912 plan by Arthur Comey.

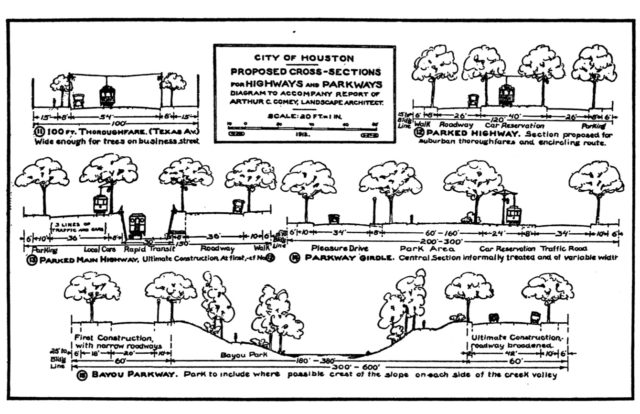

Park, transit, and street sections from 1912 Comey plan.

Park, transit, and street sections from 1912 Comey plan.

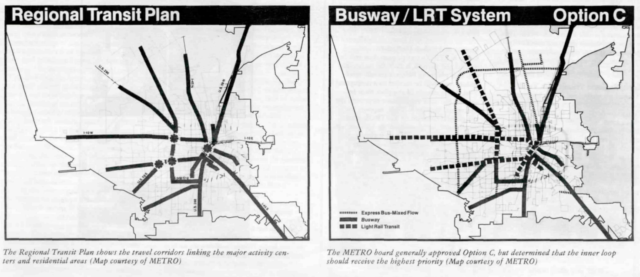

Options in 1985 METRO Regional Plan.

Options in 1985 METRO Regional Plan.

House on Beall Street, where Shady Acres meets Timbergrove. Photo: Adam Clay.

House on Beall Street, where Shady Acres meets Timbergrove. Photo: Adam Clay.

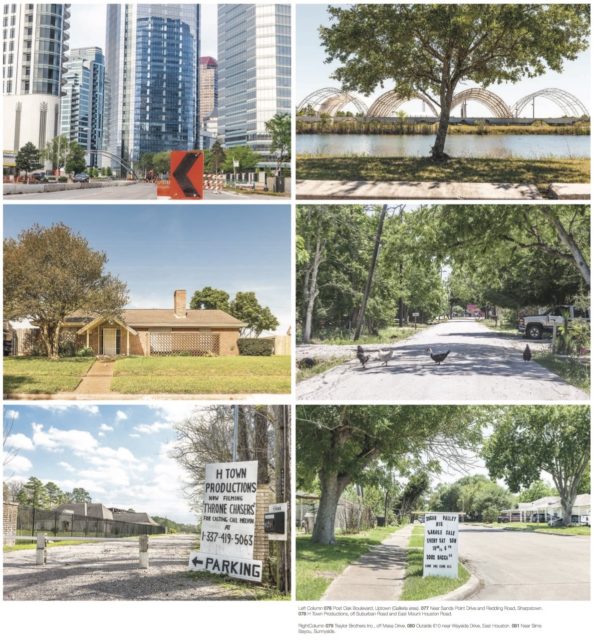

Images 76 through 81 from Cite 100. Photos: Paul Hester.

Images 76 through 81 from Cite 100. Photos: Paul Hester.

Illustration by Amir Kasem, from Cite 85, Summer 2011.

Illustration by Amir Kasem, from Cite 85, Summer 2011.

Illustration by Amir Kasem, from Cite 85, Summer 2011.

Illustration by Amir Kasem, from Cite 85, Summer 2011.

Houston’s Earliest Efforts at Planning: Port to Rail to Open Space to Automobile

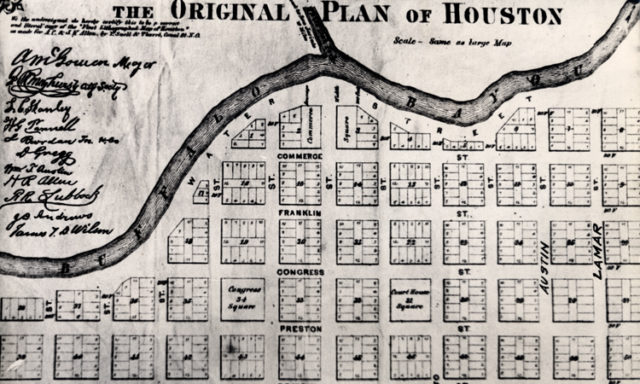

For commentary on and history of Houston's nineteenth-century planning, Monica Savino's chronicle of pre-1836 settlements in the Summer 2012 issue, Stephen Fox's "Downtown Houston: A Timeline" from 1995, and Jim Parson's lecture on the wards system in 2015 for Rice Design Alliance are good places to start. The Cite archives often refer to the original plat for Houston but do not consider it head on. Fox provided a brief synopsis for this review by email:

Houston was surveyed in the fall of 1836 by the newspaper publisher T. H. Borden, his brother Gail Borden, Jr. (the future inventor of condensed milk), and Moses Lapham. It was a nineteenth-century American speculators' gridiron plan of 62 blocks, most of them 250 feet square, wedged into a curve of Buffalo Bayou. The central thoroughfare, Main Street, bisected the town. It began opposite the confluence with White Oak Bayou. Flanking Main Street in the middle of the town site were two public squares, Court House Square and Market Square, named for the two most important institutions of local government and town life. At the south edge of the town site, two additional half-block site were reserved for a school and a church, facing away from, rather than at the heart of, the new capital city . . .

In 1839 the Congress of the Republic of Texas moved the capital inland to the city of Austin, which was planned nearer the center of the nation, in a more healthy climate, and on a broader, more generously ceremonial city plan than had been provided in Houston. Houston remained a center of importance, however, as a point of trans-shipment between Buffalo Bayou and the interior of Texas and, as A. Girard’s map of 1839 demonstrates, it began to expand as new blocks were platted to either side of Buffalo Bayou.

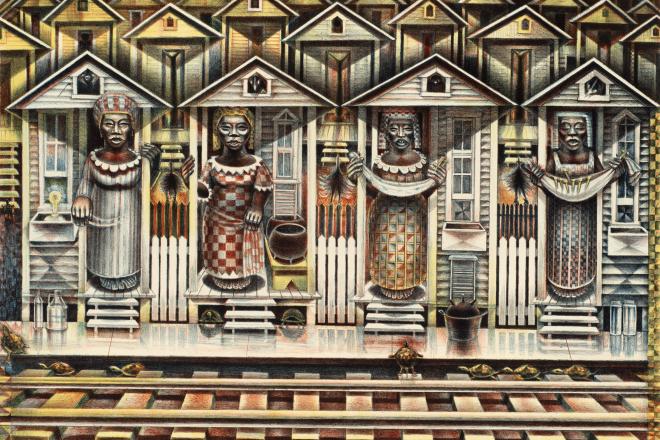

The development of Houston between 1870 and 1900 mirrored the architectural tendency to differentiate. Trade and transportation technologies were important determinants of differentiated land use. Most striking was the impact of railroads. Houston's major rail lines intersected north of the original town site --- close to the foot of the Main Street wharf, but opposite downtown. As these lines fanned out to the west (the First and Sixth wards), the north and northeast (the First and Fifth wards), and the southeast, they gave rise to working class neighborhoods, especially concentrated near the maintenance and repair shops of the Houston & Texas Central and Southern Pacific railways. Where they did not go --- downtown and the Third Ward neighborhoods to the south, along the axis of Main Street --- was where Houston's elite commercial, institutional, and residential precincts developed.

In Cite Fall 1985, Fox's “Planning in Houston: A Historic Overview” details the beginnings of the first modern citywide effort to create a plan based on a park and boulevard system, including the partially implemented Arthur Comey plan of 1912, which envisioned the bayous as linear parks. Houston attempted to pass a comprehensive zoning law by referendum and it failed five times (1929, 1937, 1948, 1962, and 1993). What is especially telling is the shift that took place in planning goals from an initial open space priority and streetcars in the twenties to a focus on automobiles in the 1940s. Fox explains, “the ‘Major Street and Thoroughfare Plan of 1943’ . . . became the city’s de facto comprehensive plan.” The freeways proposed during this period also served as a plan and engine for outward growth.

In 1978, METRO was created as the public transit agency through a one cent tax. After its formation, the agency was eager to make ambitious plans for creating a regional transit system. Perhaps most notable was that the planning effort included a robust public outreach and community engagement process through 250 meetings and consistent opportunities for public input on the 1985 Metro Regional Plan. What is significant about the plan itself, although very broad, was the way it defined transit corridors on a radial pattern emanating out from the city center to connect employment nodes.

A whole series of articles in Cite covered the dueling investments made in expanded highways, transit, hike-and-bike trails, and pedestrian infrastructure. One frequent contributor, Christof Spieler, wrote his way onto the METRO board.

1980s Onwards: Growth of Incremental Planning, Minimalist Zoning, Management Districts, TIRZs, and Empowered Neighborhood Groups

Without a comprehensive plan, Houston’s fragmented built form is shaped primarily by market forces (developer interests). In response, communities and city planners have adopted incremental but increasingly rapid changes in regulations that shape how buildings engage the public realm. These regulations include building setbacks, parking requirements, deed restrictions, minimum lot sizes, water detention rules, and others. In Cite Summer-Fall 1998, George Greanias' “Shadow Planning” describes this mix as de facto zoning implemented by the private sector instead of by the City. The salient point is that there is little accountability or transparency when the private sector acts as a “shadow planner” enabling development and land uses with huge impacts on the greater public.

Some key turning points hinted at in Fox's history are further enumerated in Cite articles of the 80s and 90s. The watershed moments occurred around ordinances and planning efforts that started to give form to the city as we understand it today. Among them are the 1982 Development Ordinance, the Metro Regional Plan 1985 (described in Cite Fall 1985 by Jeffrey Karl Ochsner), and the 1991 ordinance that established a Planning and Zoning Commission with regulatory authority. A city planning commission entity has had several starts and stops through the years. A full history of the prior planning advisory boards can be viewed on the timeline here.

In 1982, the first development ordinance (the foundation for the current set of development regulations, Chapter 42: Subdivisions, Developments, and Platting), championed by councilmember Eleanor Tinsley, created rules for building setbacks and block length, and eliminated dead end streets between neighborhoods and commercial development. The ordinance was criticized for applying a blanket approach to urban areas both inside the 610 Loop and suburban areas far outside of 610, although the “motive behind the ordinance was to keep the city a place with trees and grass” according to Joel Warren Barna's "The Development Ordinance and its Discontents" in Cite Winter 1984. Commissioner Keeland further describes a contradictory vision of Chapter 42’s intentions where, “…in 100 years the ordinance will have allowed for greater inner development, but it will make it look as if the density is still low.” Barna captures the frustration and bewilderment among developers struggling to comply with the new rules. The development ordinance came at a time when a no-zoning attitude still reigned. Planning Commission Director, Burdette Keeland, said, “ . . . I still don’t think zoning — where a bureaucrat makes decisions about what can go where in a city — can work in Houston. I don’t think there’s a planner in the world smart enough to figure out how to use land people live on. I think it’s important that we leave developers the freedom to make the choice of location for their projects.” Remarkably, this anti-zoning attitude comes up repeatedly in writings and remains pervasive among city planning officials.

“Incremental City Planning for Houston” by the late Peter Brown in Cite Fall 1985 describes the city’s efforts to create something similar to a comprehensive plan with a document called the Compendium of Plans. The idea was to gather the various neighborhood and area plans into a comprehensive set despite the attitude from then planning director Efraim Garcia who, as Brown states, “clearly stops short of seeing the plan as a normative ‘vision for the future’ for Houston, and thinks that urban design, although important, is not a critical issue.” Again, the presumptive head of planning for the city is skeptical of the value of urban design.

Although Houston itself does not have traditional zoning, several cities in the region, some of which are independent islands within Houston's boundaries, do have zoning. In “Zoning Test: Pass-Fail” in Cite Winter 1986, Rives Taylor looks at the City of West University Place’s zoning controls and shows the limitations of setbacks and buildable areas in preserving neighborhood character. Instead, he calls for a “comprehensive architectural and landscape plan” to be created as the basis for maintaining the “desirable scale and character” of West University Place. This sentiment is echoed by John Mixon in Cite Fall 1991 in “Zone First, Ask Questions Later,” indicating, “delicately formulated zoning regulations that identify and protect specific neighborhood character can enable homeowners and developers to preserve their valuable residential, commercial, and industrial investments and enable landowners and developers to reclaim Houston from its drift and decay.”

The last failed zoning referendum in 1992 took place within the publication history of Cite so you can trace the excitement and attempts to contribute to the process leading up to the vote, followed by disappoint. “5,000 Voters Can’t be Wrong” and “A Stranger Here Myself” detail the excitement and optimism in Cite Fall 1991 after the newly passed ordinance 91-63 mandated planning efforts with a “minimalist form of zoning” and the creation of the planning and zoning commission. The new planning director at the time, Donna Kristaponis, showed a more pro-planning attitude than her predecessors, stating, “The city needed a plan and that meant it needed zoning — because all previous plans since the 1920s had proved unenforceable without the sanctions that zoning provides.” In the Fall 92 / Winter 93 issue, Kelsey, Taylor, Webb, and Condon produced "Zoning Houston: A Guide," which gives a broad sketch of how zoning could work in Houston. By Fall 94 / Winter 95, Bruce Webb and William Stern come to terms with the "serious blow" of the failed referendum in "Houston-Style Planning: No Zoning but Many Zones." They note the proliferation of planning within the boundaries of special districts, the specifics of which are considered in the rest of that issue.

Mitchell Shields discusses the major revision process to the Chapter 42 Development Ordinance in Cite Winter 1999's “Revising Chapter 42” and again in Cite Summer 2000 in “Reviewing Chapter 42.” He notes that a “revelation to arise from the revision of Chapter 42 [in 1999] was the growing power of Houston’s neighborhood groups.” But the revisions, despite the fierce pushback from developers, did not ultimately satisfy homeowners and neighborhood groups because they merely set “the rules for how things get built, not what it looks like when it’s finished.”

In an attempt to make sense of who holds the power to shape Houston's built and natural environments, in the Cite Fall 2012 issue, Matt Johnson and Monica Savino compiled a "Guide to Power" that maps relevant governmental, pseudo-governmental, and non-profit entities. The profusion of Management Districts, Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones (TIRZs), and Public Improvement Districts is notable. As part of the introduction to the map, Savino and Johnson write, "Houston's vast and bewildering array of public and private partnerships can make understanding the city difficult ... The vacuum created by selective or no planning allows for myriad non-profit and public/private partnerships to resolve planning issues. In theory, this sounds like freedom, but is it?"

Current Practices

More recent plans include the General Plan, discussed in OffCite in February 2015 by Torie Ludwin, and the Bike Plan, explored in OffCite in February 2016 by Raj Mankad, but both still exist as stand-alone plans without regulated integration with formal zoning. Both were the result of public planning processes that lack enforceable mechanisms. The Bike Plan, for example, is being implemented vis-à-vis the advocacy work of BikeHouston, not as a form-based code of ordinances that require bicycle infrastructure. [Disclosure: the author is on the BikeHouston Board of Directors.] In OffCite August 2014, Jay Blazek Crossley discussed a similar caveat for street building that exists with the Complete Streets executive order of 2013. It is a suggestion that streets be built to accommodate all road users, not a mandate.

In OffCite September 2017, NuNu Chang gives an inside look at the Planning Commission in the first of a series of articles on current planning issues in Houston in Planning the Houston Way, Part I: A Tussle over Townhouses at the Planning Commission. It covers the conversation at a public hearing for a property re-plat within the Southgate neighborhood and discusses the process of approval in relation to deed restrictions and minimum lot sizes. In her March 2018 follow-up article, Planning the Houston Way, Part II: Special Minimum Lot Size, she looks at minimum lot sizes in East Montrose as a case study in how the designation restricts the subdividing of properties into smaller plats.

Post-Harvey, we are now faced with the floodplain as a potential de facto zoning mechanism that limits where and how development can occur (no new development within the 100-year floodplain and structures in the floodplains are to be significantly elevated). This is both urban form and architectural design being determined ad hoc instead of as a larger comprehensive plan — it is planning based on a single issue without integration with other systems of infrastructure and land-use.

Comprehensive planning makes common sense. Cities are multi-faceted and fluctuating entities that benefit from multivalent and holistic approaches to design. As noted at the start of this survey, most of the Cite stories on planning have this common refrain. So do the Cite articles discussed in the OffCite October 2017 flood management literature review. Yet, Houston maintains an exceptionally capitalist attitude toward planning in its constant cycle of building and rebuilding, while trivializing the benefit of a sustainable development strategy.

Refusing to be limited by Houston's bewildering array of regulatory frameworks, Albert Pope instead steps back to observe the many dispersed centers within the Houston region in his Summer 2015 article "WaterBorne: Finding the Next Houston in Bayou Greenways 2020" and abstracts to the two megaforms that do organize them, the highways and the bayous. He argues the bayous have already begun to serve as the spine for a new era of planning and we have a new opportunity to make it comprehensive.

Ashby Highrise and Other Case Studies

The heuristic nature of planning in Houston is perhaps more accurately captured not in overarching analysis but in specific case studies. John Mixon structures his discussion in Cite Spring 2011 “Zoning Around” around four vignettes of Houston’s ad hoc zoning practices. The developer’s lawsuit in response to successful neighborhood objection to the mixed-use Ashby Highrise, anthropomorphized as the claw-handed looming “Tower of Traffic,” shows the city acted arbitrarily because, “the city, operating without clear standards, used its formal power to withhold driveway permits as leverage to impose zoning-type limits on development.” Mixon calls the Ashby Highrise and other examples “inefficient and borderline illegal.” He also highlights the negative impacts of no zoning on poor communities of color.

The city is full of such examples. “Houston: A No-Zoning Zone” is a June 2015 NPR Here & Now report in which Cite editor Raj Mankad and KUHF reporter Gail Delaughter point out disjointed developments: a church that became a strip club before becoming a fancy restaurant; a duplex apartment that became an office and welding shop; and a seventeen-story high-rise tower adjacent to single-family houses. Paul Hester's photo essay in Cite Summer 2009 documents troubling examples along industrial fenceline communities, an issue further demonstrated in Mankad's June 2014 OffCite article on Grace Lane and his August 2017 Grist article on Manchester.

In Cite August 1982, William H. Anderson and William O. Neuhaus, III have a fascinating piece, “Trading Toilets: The Subterranean Zoning of Houston” — the cover story of the first issue of Cite — a discussion of how sewer capacity in the 70s and 80s became a limiting factor on development. Houston’s explosive growth after World War II outpaced its sewer treatment capacity, which resulted in a moratorium on new development inside of 610 (except Downtown). Anderson and Neuhaus state, “The sewer moratorium . . . controlled development within the 610 Loop while allowing Downtown Houston and the newly developed areas ringing the city outside the Loop to grow almost without restriction.”

While sewer capacity is no longer the main constraint on infill development, the reliance on infrastructure as de facto planning over comprehensive planning has come full circle after the devastation of Hurricane Harvey. Although the latest regulations and proposed regulations around flood mitigation will have profound impacts on what is built and preserved, and how it looks, public discussion of the impact on the built environment and public realm is minimal. Though land-use regulations have proliferated in the last few decades in the attempt to balance order and chaos, these incremental solutions are inadequate to shape equitable and resilient development of the third largest city in the US.

Further Reading

Anderson, William H. and William O. Neuhaus, III. "Trading Toilets: The Subterranean Zoning of Houston." Cite 1. August 1982.

Barna, Joel Warren. “The Development Ordinance and Its Discontents.” Cite 5. Winter 1984. Offcite.org. Jan. 1, 1984.

Brown, Peter. “Incremental City Planning for Houston.” Cite 11. Fall 1985.

Chang, NuNu. "Planning the Houston Way, Part 1: A Tussle over Townhouses at the Planning Commission." OffCite.org. Sept. 1, 2017.

Chang, NuNu. "Planning the Houston Way, Part II: Special Minimum Lot Size by NuNu Chang." OffCite.org. Mar. 21, 2018.

City of Houston. “Timeline Of Key Houston Planning Dates, 1913 - Present.” City of Houston. Updated May 30, 2018.

Crossley, David. “The City Beautiful? Form-Based Development Code in Houston.” Cite 74. Spring 2008. .

Crossley, Jay Blazek. "Complete Streets Are Coming to Your Neighborhood Soon. We Hope." OffCite.org. Aug. 27, 2014.

Curtis, John. "5,000 Voters Can't Be Wrong: How Zoning Came to Houston." Cite 27. Fall 1991.

Delaughter, Gail. "Houston: A 'No-Zoning' Zone." NPR, Here & Now. wbur.org. June 23, 2015.

Fox, Stephen. "Downtown Houston: A Timeline." Cite 32. Fall 1994 - Winter 1995.

Fox, Stephen. “Planning in Houston: An Overview.” Cite 11. Fall 1985.

Greanias, George. “Shadow Planning.” Cite 42. Summer-Fall 1998.

Henderson, Archie. “Here’s Looking at Euclid.” Cite 27. Fall 1991.

Hester, Paul. "Edge Conditions." Cite 79. Summer 2009.

Johnson, Matt and Monica Savino. "A Guide to Power." Cite 90. Fall 2012.

Kelsey, Virgina, Rives Taylor, Joe Douglass Webb, and Patrick Condon. "Zoning Houston: A Guide." Cite 29. Fall 1992 - Winter 1993.

Kristaponis, Donnas, William Stern, Rives Taylor. "A Stranger Here Myself." Cite 27. Fall 1991.

Ludwin, Torie. "Opening Conversations on Houston’s General Plan." OffCite.org. Feb. 6, 2015.

Mankad, Raj. "As Houston plots a sustainable path forward, it’s leaving this neighborhood behind." Grist.org. Aug. 15, 2017.

Mankad, Raj. "Saving Grace: A Small Experiment by Two Architecture Students Led to a Big Struggle for Their Neighborhood." OffCite.org. June 20, 2014.

Mankad, Raj. "Houston’s Draft Bike Plan Lays Out Ambitious Vision for City’s Future." OffCite.org. Feb. 18, 2016.

Mihalic, Falon. "Houston Flood Management, A Literature Review: What We Know and Where We Go from Here." OffCite.org. Oct. 17, 2017.

Mixon, John. "Zone First, Ask Questions Later." Cite 27. Fall 1991. OffCite.org. Sept. 1, 1991.

Mixon, John. "Zoning Around." Cite 85. Spring 2011. OffCite.org. Apr. 27, 2011

Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl. “The Metro Regional Plan 1985.” Cite 11. Fall 1985.

Parsons, Jim. "Houston of Houston's Wards." Vimeo.com. Rice Design Alliance Civic Forum. March 24, 2015.

Savino, Monica. "The Fourth Choice: Paper Cities on the Bayou." Cite 89. Summer 2012.

Shields, Mitchell J. "Reviewing Chapter 42." Cite 48. Summer 2000.

Shields, Mitchell J. "Revising Chapter 42." Cite 43. Winter 1999. OffCite.org. Jan. 1, 1999.

Taylor, Rives. “Zoning Test: Pass-Fail?." Cite 16. Winter 1986.

Webb, Bruce. “Through the Zoning Glass.” Cite 27. Fall 1991.

Webb, Bruce and William Stern. "No Zoning But Many Zones." Cite 32. Fall 1994 - Winter 1995.