“The City Houston is open for business,” Mayor Sylvester Turner announced eight days after Hurricane Harvey began its roughshod path through the city. Downtown’s office buildings are humming but a ten-minute drive northeast exists a parallel universe named Kashmere Gardens.

Kashmere Gardens is a historically African-American community with a growing Hispanic population and one of the poorest in Houston. The median household annual income in this community averages $22,000 with 43 percent of households having an income less than $14,000. Over 55 percent of the population are unemployed or out of the workforce.

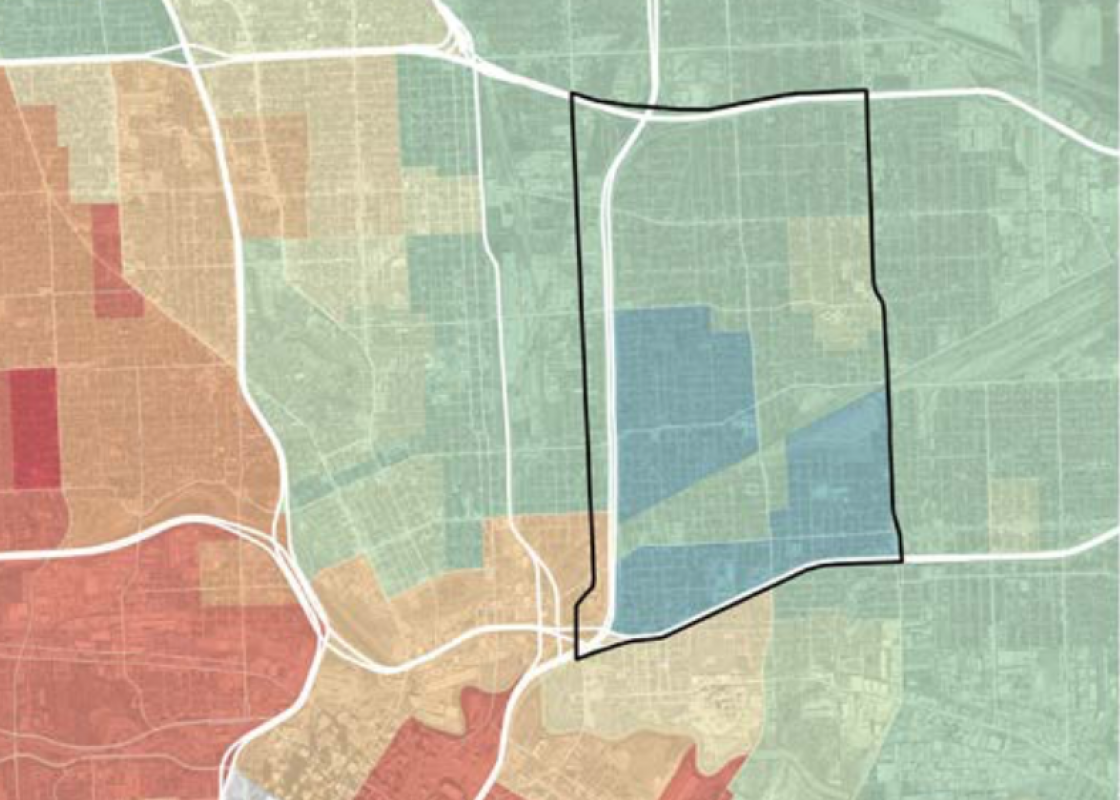

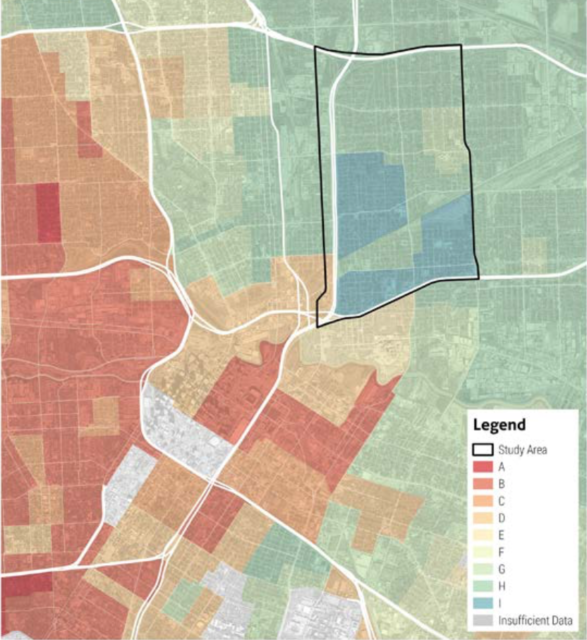

Market value analysis of Kashmere Gardens, outlined in black, and adjacent neighborhoods. Source: HGAC Kashmere Gardens Livable Centers Study.

Market value analysis of Kashmere Gardens, outlined in black, and adjacent neighborhoods. Source: HGAC Kashmere Gardens Livable Centers Study.

Kashmere Gardens lies just beside Hunting Bayou and was one of the first areas to flood during Hurricane Harvey. It has been in a terrible waiting game ever since.

Residents watched as waters rushed into their one-story homes in the dark hours of August 26, with most waiting until daybreak to safely evacuate. Families waited for as many as eight hours. Some called 911 and waited. Others managed to wave down Houston Fire Department and garbage trucks. Many attempted to evacuate by foot. There were multiple accounts of flooding that reached residents’ necks as they moved towards higher ground. Small children and the elderly were carried or pulled on improvised flotation. Parents held tight to the arms of older children who were told to paddle their feet hard.

Keith Downey, incoming President of Kashmere Gardens Super Neighborhood #52, estimates over 60 percent of his constituents’ homes flooded. But this was no unprecedented “gee-whiz” event. Much of of Kashmere Gardens falls within Harris County Flood Control District’s (HCFCD) fundamentally-flawed “100-Year flood plain.” It is inexplicable to residents that so few rescue and recovery resources were positioned for stranded citizens in a known flood-prone area and how little government presence has been felt on their streets in the weeks since.

Though the waters have receded, the waiting in Kashmere Gardens continues. But waiting should not be confused with doing nothing. Cleanup has been backbreaking and slow. The FEMA process has been long and confusing. Provisioning basic necessities without transportation has been nearly impossible. Urania Clark has waited beside her flooded home and car on Hoffman Street for two weeks now. Her job as an HISD school crossing guard has been delayed due to school closures so she’s unsure when her first paycheck will bring money in for storm-related expenses. In the meanwhile, she keeps a grim vigil for a FEMA agent to arrive. She has meticulously documented the soggy remnants of the life she shared with her husband and eight year-old daughter: the recently purchased sofa, the flat-screen television, even the 23 year-old wedding gifts whose sentimental value cannot be monetized. She was proud of her tidy home and hoped the inspector would assess personal property loss in situ rather than as a tangled pile of debris at the curb. But this waiting is over. The landlord arrived before FEMA and has placed a lock on the front door, citing storm damage as cause to break her family’s lease.

“I can’t believe it,” as Ms. Clark lets out a tired, exasperated sigh. “FEMA hasn’t come but the management company is trying to put us out. They say if they don’t get our stuff out, they’re gonna trash it. Is it even legal? The least they can do is give us time so everyone can see FEMA. I saw it on TV… in Kingwood the army trucks were all lined up to help people. They were helping people: everyone, everywhere. I got none of that help, nowhere. They forget about the little people like us. But we work and we pay taxes. Just like the people in Kingwood. They forgot about us.”

Ms. Clark is, in many respects, correct. Houston is a high tax city for the poor. The poorest 20 percent pay more of their income in taxes than any other income group in the state and have the sixth highest state and local tax bill in the nation (12.6 percent of income). Despite the fact that Houston is home to 24 Fortune-500 companies and boasts a regional GDP approaching half a trillion dollars per year, Harris County’s $100 million annual spend on flood control is paltry compared to other flood prone areas of the country. For example, adjusted for population, Southern Florida outspends Harris County 3 to 1. More generally, infrastructure projects tend to first serve affluent and politically-connected communities and business interests, resulting in what some experts term “ecological gentrification.”

Kashmere Gardens residents who feel forgotten by their government depend on each other. They piled into each other’s trucks in search of higher ground during Harvey’s lashing rain. They help each other carry water-logged albums into the sun, hoping one or another photo can be saved. They pass FEMA paperwork between themselves, making twice-certain which form needs to be mailed and where. Pastors have opened their doors to feed many more than their congregation. Neighbors from surrounding areas of Houston are coming with bleach and masks and sandwiches.

Keith Downey, an architectural designer who worked as project manager for New York Parks and Recreation and incoming president of Kashmere Gardens Super Neighborhood #52, is helping coordinate these efforts. Driving his car down Minden Street, he stops to check in on an elderly woman. “Let’s talk to this resident and help get her heart changed.” Changing hearts and connecting them to one another is Mr. Downey’s simple, motivating mantra: “No matter where you live or where you lay your head, it’s about people caring about people. It’s not about religion, it’s not about creed, and it’s not about color, it’s about people helping people.”

Kashmere Heights is recovering through grass-roots organization. Mr. Downey has joined forces with Huey German-Wilson, president of Trinity Gardens Super Neighborhood, and Kenneth Williams, President of Kashmere High School Alumni Association to become a triumvirate connecting volunteers and donations to needy citizens within the communities of Northeast Houston. They use their deep connections to learn which congregation halls didn’t flood and call the pastor to see if it can be quickly repurposed into a donation center. They know which street corner might be the best location to serve up 200 Operation BBQ meals in eight hours' time. They learn which addresses need cleaning supplies and which need sheetrock demolition and match these needs with a myriad of larger citywide volunteer groups. They go door-to-door and use Facebook to connect with their social-media savvy constituents. Their phones erupt with calls and texts. Each one is answered.

Volunteer work crews and food distributions will inevitably thin as volunteers return to work and humanitarian aid migrates to communities affected by Hurricane Irma. When that happens, the longer-run challenges for Kashmere Gardens are formidable. Positioned between an industrial area and a rail corridor, Kashmere Gardens has also been isolated from the neighborhoods that once bordered it. Decades of road infrastructure projects, many of which serve Houstonians’ unquenchable thirst for cheaper land on the city’s periphery, criss-cross their “drive-by” community. Mr. Downey remembers his childhood, when Kashmere Gardens boasted quality shopping and services. But as the community became more geographically isolated, the number of local businesses dwindled. Today, it is classified a food desert where transportation is impeded by lack of sidewalks, pedestrian crossings and inadequate public transportation service. Poor drainage due to illegal dumping, a dearth of quality affordable housing, and lack of sustained attention by the City of Houston to these longer-term problems remain obstacles. When asked where high quality, affordable housing might be made available for residents permanently displaced by Harvey, Mr. Downey was eager to point out long-empty tracts of land in the immediate area, some of which were owned by Houston I.S.D.

Mr. Downey’s community wish list is echoed and elaborated upon in the 2017 Kashmere Gardens Livable Centers Study undertaken by the Houston-Galveston Area Council in conjunction with the Northside Management District. He served on its advisory committee. The report recognizes that, in an era booming with urban infill development, Kashmere Gardens’ proximity to downtown Houston makes it prime for longer-term market appreciation. The study, created with community input, sets forth a ten-year vision for Kashmere Gardens that is aligned with city goals and compatible with residents’ identified needs. The report proposes attracting public-private funding to jump-start the housing market through a combination of new mixed-use and single family construction, and construction assistance and related funding for homes in disrepair, particularly those owned by senior citizens who lack the mobility and resources to do so otherwise. Other recommendations include upgrades to local infrastructure, including community gateways, railroad crossings, and increased public transportation options such as extending Community Connector Metro service that would provide user-generated “demand-response” service, as well as environmental mitigation of known soil and water contamination in the area.

Kashmere Gardens’ long-term revitalization will also depend on creating flood resilient housing and taming Hunting Bayou waters during extreme weather events, like Hurricane Harvey. Hunting Bayou exceeded its banks multiple times since 2000, despite improvements in past years, including widening and deepening of the flood channel and construction of the Homestead Basin, which was due to enter its third and final phased construction this August. Harris County Flood Control District’s (HCFCD) Hunting Project site work began in 2007 and is an estimated ten to fifteen percent finished with completion estimated in four to six years’ time.

Hunting Project includes plans to mitigate flood risk, in part, through the voluntary and involuntary relocation of 40 homes within Kashmere Gardens’ 100-year flood plain. This process has been a years-long effort with some, but certainly not all, residents amenable to relocation. Anxiety and resistance are keenly felt by residents with deep community attachments. Kevin A. Lynn’s 2017 study of Kashmere Gardens highlights these relocation hurdles:

Monetary compensation may not be suitable to address certain community and social effects. The social impacts are likely to be especially significant for communities of color. Political outsiders who make plans for relocation often have inaccurate impressions of their needs and priorities, overlooking attachment to neighborhoods, and strong social ties. - Kevin Lynn

As she cleaned out her 79 year-old mother’s flooded Kashmere Gardens home, Vera Matthews distilled Mr. Lynn’s research findings more bluntly: “We were raised right here until I got married. Someone has been right here, forever. [Relocation] is not always convenient for elderly people. She has her community that she is familiar with so why would she want to move all the way out to Spring or Cypress or somewhere else? Transportation is not there. You have to have a vehicle. ”

The resilience of the Kashmere Gardens community as it undertakes the hurricane recovery process stands in tension with the endemic economic vulnerabilities residents face while doing so. Amid uninsured losses, FEMA denials, and lost wages due to the storm, the financial and emotional stress of rebuilding is enormous. To a great extent, political and policy decisions will help shape the longer-term pace and direction of revitalization. With sufficient political will and funding, Kashmere Gardens Livable Centers Study offers one promising blueprint for its post-Harvey future.

Further Reading

Asakura Robinson with Golder & Associates. Kashmere Gardens Livable Centers Study, Houston-Galveston Area Council, 2017.

Lynn, Kevin A. Who defines 'whole': an urban political ecology of flood control and community relocation in Houston, Texas. Journal of Political Ecology. Vol.24, 2017.