Good morning, Mr. Downey:

I did fill out the application for Harvey [Home] Connect. Although it looks like I am being redirected down the same road. I registered with [the first organization]. They said that everything was good but called back in three weeks and said they are no longer helping my zip code. So I was routed to SBP. It took three weeks to receive my paperwork from [the first organization]. SBP was asking for my income update but that was already submitted. I told them I was handicapped and my income had not changed in three weeks. Plus they wanted my deed. I have given them my tax statement already. Others [I have contacted]: JJ Watt [Foundation], City of Houston, Lone Star [Legal Aid, Harris County Agency on Aging, and] several more organizations. With all the above plus other places I tried, can you understand what state of mind I am in now.

Regards, Rosa Randle.

Rosa Randle, a senior, isn't the only Kashmere Gardens resident wandering through this labyrinth without a map. She remains in limbo. Lacking critical assistance a year after Hurricane Harvey landed, Ms. Randle’s story is all too common. Mr. Keith Downey, Kashmere Gardens Super Neighborhood President, says he receives calls and texts like hers daily. Nearly one year after reporting on Kashmere Gardens after Harvey, I found residents and community leaders remain occupied with short-term relief and recovery even as they pursue long-term planning.

“Posting a flyer just won’t do,” Mr. Downey quips when asked how residents – many of whom lack internet access – successfully connect with Harvey relief services. Handshakes. Hugging. Hearing. That is the gospel Mr. Downey preaches. Human connection helps build trust, he says, and that personal touch encourages residents to advocate for their own needs. He estimates at least 40 percent of Harvey-affected residents in his community are living in homes still needing remediation, are in various stages of repair, or remain displaced altogether and faults his community’s lack of political and economic influence for delays in receiving assistance. FEMA data analysis by non-profit Texas Housers confirms that the highest concentration of residents with unmet housing needs a year after Harvey are in low-income, minority neighborhoods like Kashmere Gardens, where the median household income hovers around $23,000.

Keith Downey at August 18, 2018 Community Design Charrette at University of Houston. Photo: Raj Mankad.

Keith Downey at August 18, 2018 Community Design Charrette at University of Houston. Photo: Raj Mankad.

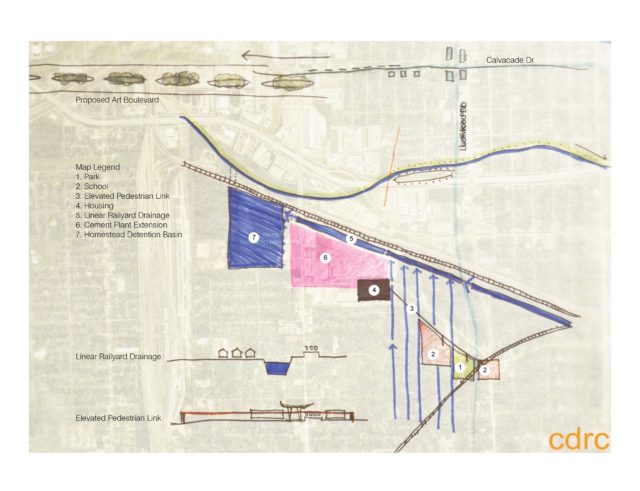

Sketch from Kashmere team showing comprehensive strategy for drainage, retention, and walking paths to parks and schools. Courtesy Community Design Resource Center, University of Houston.

Sketch from Kashmere team showing comprehensive strategy for drainage, retention, and walking paths to parks and schools. Courtesy Community Design Resource Center, University of Houston.

The Center for Disease Control ranks Kashmere Gardens among the nation's most socially vulnerable neighborhoods, as determined by “degree to which a community exhibits… high poverty, low percentage of vehicle access, [and] crowded households.” In short: Hurricane Harvey continues to complicate lives that were complicated enough already.

The canyons of flooded waste are gone making ongoing struggles less visible. It's hard to understate the extent of loss in this community of 10,000 residents. Based on City of Houston estimates, the Community Design Resource Center at the University of Houston found that a staggering 79 percent of all homes in the Kashmere Gardens Super Neighborhood flooded during Hurricane Harvey. Data from the 77028 zip code, which includes parts of Kashmere Gardens, show there were twice as many applicants with FEMA Verified Loss (FVL) as other Harris County zip codes. Just half of these FVL applicants received any level of FEMA assistance. Of those households “lucky” enough to get FEMA aid, four in ten still had thousands of dollars of unmet needs in that zip code. This substantial gap in assistance has been met in piecemeal fashion through an estimated 50 organizations and agencies servicing the area. But as Ms. Randle’s experience illustrates, securing help is a long and frustrating journey.

A glance outside the car window is visual testimony to these facts. As the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Harvey approaches, while the canyons are gone, there are still piles of debris dotting the roadside. We park beside one and knock on a nearby door. Shirley Paley invites us into the modest two-bedroom home she has owned since the 1990s. Furniture sits in cellophane wrapping and a faint smell of paint hangs in the air. Ms. Paley is waiting for the contractor to finish final projects, but is praying hard that she will be able to finally move back in a few weeks’ time. “I’ve had to be my own cheerleader,” she says while mulling over the past year.

Bam, Bam, Bam. Ms. Paley weaves her post-Harvey story in a breathless stream, each tragic turn of events followed on its heels by yet another. She sat through the storm with her 11-year-old granddaughter and 17-year-old special-needs grandson. For the first time, her house took on floodwater. Finding no temporary housing, she moved her family into her car in the driveway for the first few weeks. Getting her home gutted and repaired has been an uphill battle from start to finish. Volunteers offered to muck her home, but threw all of her personal items in an indiscriminate jumble on the curb. She found her grandson’s Social Security card and other important paperwork lying in the driveway. She sent them away, deciding to salvage important belongings on her own and managed the cleanout herself. A state-hired contractor began more intensive rehabilitation work, but their work was so shoddy that she was forced to use her limited budget to fix their mistakes.

The cost of remediating her home was more than double the $11,000 FEMA provided. Without savings to cover the difference, her only alternative was to apply for a $25,000 Small Business Administration (SBA) loan. But SBA deducted the FEMA payment from the proceeds of that loan, effectively negating the FEMA award altogether. She will now need to repay the full $25,000 with interest, making her monthly loan payment higher than her existing mortgage and more than doubling her housing costs for years to come. All this will account for the lion’s share of her fixed income. Even with the SBA loan, she has needed to find help to cover other Harvey-related expenses. Like Ms. Randle, Ms. Paley has been navigating an alphabet soup of charities and non-governmental organizations, securing assistance from YES Prep charter school, a local church, Baker Ripley, Texas PREP, and Northeast Next Door Redevelopment Council.

All the while, Harvey’s emotional effects were becoming more serious for Ms. Paley’s grandchildren. Changes to their living routine were fraught for her autistic grandson, but an even more profound psychological change was seen in her granddaughter. The hurricane seemed to trigger a visceral trauma response: emotional rages and profound depression surfaced in a girl who was a cheerful, straight-A student only months before. Suicide attempts precipitated several in-patient hospitalizations in the months to follow. One day, Ms. Paley met with her granddaughter’s therapist. When Ms. Paley was asked how she was coping with multiple crises at once, she replied, “When the kids go to bed, I weep into a towel.” It is this simple. It is this hard.

The mental health effects of the Hurricane Harvey are currently being evaluated as part of a joint effort between Rice University, the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Houston Health Department. If Hurricane Katrina is any indication, their results may be sobering: post-Katrina studies show new mental health conditions were reported in half of respondents and these conditions often worsened over time, with suicidal thoughts doubling a year after the storm compared to the months immediately following it.

Down the road from Ms. Paley, I catch up with Urania Clark. She has moved four times since we met in the days following Hurricane Harvey. First, to a squalid hotel room, the only one she could find that accepted FEMA’s Transitional Shelter Assistance. Next, she found a two-bedroom apartment that the landlord vowed had not flooded. But soon after moving in, her daughter Uriah began to feel sick and had frequent nosebleeds while Ms. Clark and her husband experienced near-constant headaches. One day, she opened a utility closet to find the source of their illnesses: thick swaths of black mold were crawling up the walls. Texas law does not obligate owners to disclose whether a property flooded, but with a sick daughter, Ms. Clark had no time to fuss over legal fine print. The Clark family up and moved once again, losing their deposit in the process. They returned back to her old apartment complex. When the family moved to another unit in the same complex and ownership changed, their new landlord increased her rent by hundreds more than what she paid for exactly the same accommodations only a year ago. She is too exhausted to contemplate yet another move, at least for now.

“Things may look the same as before the storm, but they just aren’t. Something still feels, I don’t know… missing,” Ms. Clark muses. The lost ground she has not recovered includes the sense of belonging she shared among her old neighbors, many of whom did not return. And rain still rubs her nerves raw. She wants to find a pier-and-beam home that sits at a comfortable distance above ground, but that dream lays somewhere in the hazy future.

Hazy or not, the future will come and preparing for the next storm rather than the last one is high on Mr. Keith Downey’s list of priorities. He is hopeful that the $2.5 billion Harris County Flood Control District’s bond will pass this month, which will allow completion of necessary drainage improvements to nearby Hunting Bayou. He is less pleased with the City of Houston’s recently released Draft Local Action Plan: Hurricane Harvey Housing Recovery that outlines a response strategy going forward. “One size does not fit all,” Mr. Downey says. He believes the City’s Draft Plan relies on top-down edicts that do not take into account the differing needs of Houston communities, especially ones that are the most at-risk. For example, Kashmere Gardens has half as many households owning a car as the rest of Houston but twice the number of disabled residents, as well as many seniors who live alone. This confluence of factors, in addition to high poverty and low access to food stores, makes the community especially vulnerable during a disaster. A differentiated city plan that recognizes low-income communities will need more assistance in the wake of devastating events like Hurricane Harvey would provide a more robust plan for Kashmere Garden’s future.

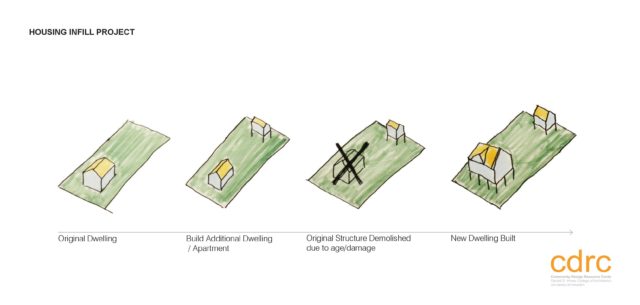

Creating a thriving community will rely on more than flood mitigation and resilient architecture, though. Reversing generations of disinvestment in the Kashmere Gardens community is a big first step. A forward-looking blueprint for Kashmere Gardens will rely on quality-of-life improvements, like affordable housing that does not displace longtime residents from their community, installing sidewalks that keep students safe from cars and train crossings on their way to school, and expanding retail presence that gives the neighborhood convenient access to critical purchases, like healthy food and medication.

Towards that end, this August, more than forty professionals and community stakeholders joined together at the University of Houston to envision what the future of Kashmere Gardens might look like. Under the direction of Susan Rogers, this Collaborative Community Design Initiative began in January, when students enrolled in the Community Design Workshop at the Hines College of Architecture and Design at UH and began researching, collaborating, and strategizing. The Kashmere Gardens student team included Reagan Cameron, Catalina Morales, Rafael Araujo, and Salil Kenny. Jose Solis, Cheryl Vazquez, and Preetal Shah participated in the charrette. UH’s Community Design Resource Center will take the ideas from the students, the charrette, and further collaborate with community stakeholders and partners to develop the ideas further, culminating in a publication and exhibit. The Community Design Resource Center is committed to honoring Kashmere Gardens’ strong social fabric and proud history while also addressing the neighborhood's fundamental resource and infrastructure challenges, which existed long before Hurricane Harvey blew into town as a means to support a more resilient community.

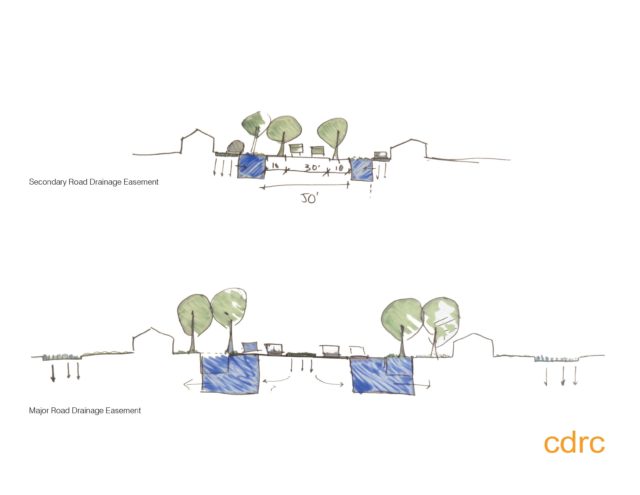

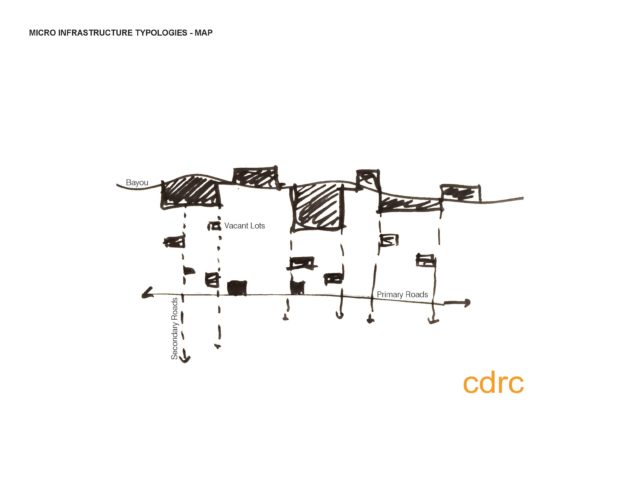

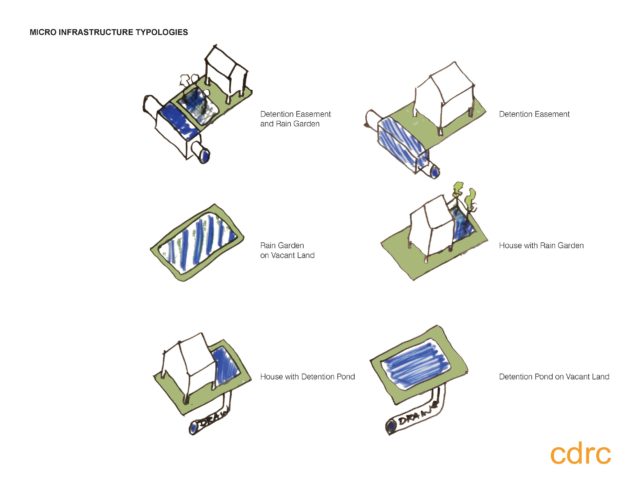

Giant maps pinned onto the walls of the meeting space provided powerful graphic confirmation that, over the past decades, Kashmere Gardens has been geographically isolated from neighboring Houston communities. Successive waves of infrastructure “improvements” like widened highways and railway lines have constrained movement of people into and out of the neighborhood. Railroad tracks, highways, and Hunting Bayou border all sides of the community, creating an island effect. Nearby rail yards have had a secondary result of altering drainage patterns and exacerbating flooding. The participants in the UH Community Design Resource Center charrette envision a plan whereby the right of way bordering these rail lines is repurposed to act as a greenway and linear retention basins during a flood event to facilitate drainage. Other ideas include building micro-infrastructures like rain gardens and easements on residential lands that experience flooding due to street runoff. Kashmere Gardens is dotted with vacant lots, many of which are used as illegal dumping sites that can also hinder street-level drainage. Creating public art zones on these vacant lots hold the promise of transforming visual blight into hubs for community events and civic pride.

If any of these ideas are to take root in Kashmere Gardens, a large web of interdependent levers --- including City and State agencies, public utilities, and private enterprise --- will need to be coordinated. Greater Houston’s Local Initiatives Support Corporation’s (LISC) Great Opportunities (GO) Neighborhoods initiative is stepping in to help activate Kashmere Gardens’ revitalization plans over this longer term. As the nation’s largest and oldest community development financial institution, LISC has earned its bona fides. Their GO Neighborhoods initiative is focused on revitalizing specific Houston communities by assisting residents in creating a long-term vision for growth. It will provide essential case management support and help to identify and secure additional funding opportunities.

The residents of Kashmere Gardens are not content to leave their future solely in the hands of City Hall, academics, or nonprofit groups. As the thermometer hovered at 95˚ on a recent Sunday afternoon, more than 85 Kashmere Garden residents packed into a temporary building at St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church on Dabney Street for a neighborhood civic meeting hosted by the church and The Metropolitan Organization (TMO). The turnout was four times greater than a year before. Hurricane Harvey caused heartbreak and emptied wallets, but has also have given residents a taste of empowerment. They have been advocating for their families all year, and if this meeting turnout is any indication, are keen to bring their attention and energy to the larger challenges in the community. Cleaned-up streets, repaired houses, and at least one planned repair of a collapsed drain have come about from collective action. Just turn your ear their direction: the citizens of Kashmere Gardens have ideas and are eager to make them real.