This article is part of a special series on Sharing, the theme of the Rice Design Alliance Fall 2018 Lecture Series organized in collaboration with PLAT Journal. The relationship between the sharing economy and the built environment is the subject of the latest issue of PLAT, an independent architecture journal produced by the students of Rice Architecture. Its content broadly explores the implications of an economic paradigm that is already at work and shaping our lives in major ways, from how buildings are designed to how the tools architects use impact how we share. The journal features contributions from designers across the planet, but what are the implications for a place like Houston with a culture that strongly values individual freedoms and property rights, and where owning your car and house signals success? Cite Editor Raj Mankad looks at how a global trend is taking root in Houston and already overturning long-held assumptions about the city.

Two men play ping pong next to the long bank of tenth-floor windows overlooking Main Street on a Wednesday at 3:30 in the afternoon. The vibe at WeWork is like a slice of Silicon Valley has been dropped into the middle of Houston’s ho-hum oil and gas industry. A group of men lounging in a couch — one of them wearing a bright red sport coat with a patterned handkerchief tucked in his pocket — talk about, among other things, using the light rail to commute from Midtown to this co-working space in Downtown Houston. A few steps away at the bar, a tall man in a beard pours himself a beer out of a tap while a woman grinds coffee beans in a cappuccino machine. At the other end of the floor, half a dozen people sit silently before their laptops at long tables. According to employees giving me a tour, the ten floors at the 708 Main location of WeWork opened in April are already at 80 percent capacity with more than 800 members, a sign that the "sharing economy” is expanding quickly in Houston.

Chances are you have participated in the sharing economy already by buying something used on EBay, donating to a crowdfunding campaign, hiring a car through Uber, staying in an Airbnb, riding a BCycle, or even having your dog walked through Rover. Cities have always been about sharing — when thousands of people live in the same area sharing is the only option — but this latest tech-infused iteration raises new questions about buildings, streets, regulations, labor rights, and more.

The new comes with old bones. For its Downtown location, WeWork chose a historic landmark redeveloped and rebranded by a partnership of Lionstone and Midway, the developers behind CityCentre, as The Jones on Main, “a historically hip Houston landmark.” The WeWork location is adjacent to the 1927 Gulf Building built by Jesse Jones and designed by Alfred Finn, Kenneth Franzheim, and J. E. R. Carpenter. While the WeWork entry lacks the grand lobby of the main entrance at 712 Main, the space takes on character from the old bricks, exposed ducts, and some Deco details. According to my tour guide, about 10 percent of the members pay $250 per month for access to the open common spaces which feature a profusion of seating possibilities — round tables, bar stools, rows of rectangular tables, booths, and couch after couch with no two alike. Some areas, like the glass-walled conference rooms, are rather bleak. For $350, you can share a small room with four desks, each with a tiny filing cabinet. On some floors, part or all of the space is dedicated to a single company.

“I pay to have access to the common areas at WeWork,” says Brad Snead, a lawyer who lives in the Heights and does not use a car. “My office is in the Galleria area, but I’m Downtown quite a bit for work, community, or social events. I use the Downtown WeWork more as a home base between or around events, not as my primary office. For example, sometimes I have morning hearings at the courthouse. Rather than come to the office first, I bus directly from the Heights to Downtown, work there, print things if needed, and then head over to the courthouse.”

The Downtown WeWork is just one of 40-plus co-working spaces in Houston, though other companies are decidedly more conventional. (No ping pong.) Some spaces are locally owned while others, like WeWork, are part of rapidly growing global corporations that have put pressure on traditional office developers to adapt. TxRx Labs is more of a maker space than an office environment. Network while learning to solder. The Station Houston is a strong local effort to "transform Houston into a world-leading hub for technology innovation and entrepreneurship" with a deep bench of mentors and other resources. Hines has announced its newest tower in Downtown Houston, designed by Pelli Clark Pelli, will incorporate 20,000-square-feet of co-working space.

With Houston attempting to establish an innovation corridor and with Rice University's project at the former Sears building as one node, the co-working spaces already in place give a hint of an emerging "ecosystem." At WeWork, for example, the Flatiron School holds its coding camps. For $14,000, become a data scientist in five months! Are you an innovator and entrepreneur, or a gig economy creative, but you need help managing your enterprise? WeWork links you to health insurance options through TriNet, payment processing through Chase, accounting through InDinero, and small business loans through Bond Street. Add to that stress relief with an occasional free chair massage and networking over pumpkin spice lattes.

The “sharing economy” has upended assumptions not only about offices but bedrooms too. Houston has had a cooperative housing non-profit for several years, though the latest version --- less hippy and more dorm-like --- that is rapidly spreading in New York City has yet to arrive in Houston.

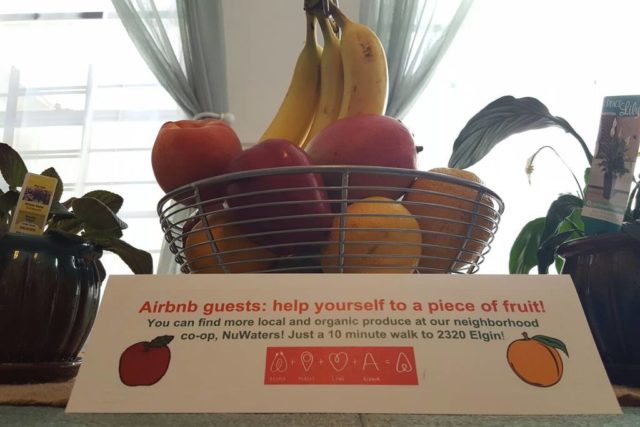

Ed Pettitt is a resident of Houston’s Third Ward who has shared his home with about 2,500 people since 2016 through Airbnb. He converted two spare bedrooms, a shed, his sunroom, and the loft space above his garage into Airbnb guest rooms while adapting the office and the garage itself into lounges with wifi. Some guests are students who stay for a semester, others stay overnight while trekking across the world. A young man from Botswana sits on a couch where a car once parked.

In many other cities, the rise of Airbnb and other sharing economy companies has generated a backlash. New Orleans has temporarily banned new permits for rentals through Airbnb because of concerns voiced by residents about affordability and the impact on communities when large numbers of whole houses are rented out on a short-term basis. Over the last year in Dallas, several companies launched dockless bike share options and then disappeared, and e-scooters have risen in their place. In 2016, Uber and Lyft withdrew from Austin when regulations, including a rule that drivers had to be fingerprinted by a third-party service, were upheld by voters. A local company sprung up called Rideshare Austin but when the state legislature passed a law that supersedes local regulations, Uber and Lyft returned.

Platform apps like Uber or Airbnb may enable entrepreneurial individuals to make money themselves, but the company is still one whose goal is to generate value for its investors. Sharing is friendly, but its beauty is at times only skin-deep, in economic terms. While most people are familiar with the obvious benefits of sharing, its difficulties are the subject matter for the three lectures of the Rice Design Alliance Fall 2018 Lecture Series, co-organized with PLAT. The three speakers are concerned with the labor rights of architects, architecture and the media, and large-scale urban development, respectively. The first of these lectures, featuring the work of architect Peggy Deamer, took place on October 10. In the lecture and this podcast interview, she discussed why addressing their own precarious working conditions will help architects to design democratic spaces and design in solidarity with other workers.

"These platforms bring about liberating possibilities for transnational networks to coalesce around food, shelter, transportation, communication, and talent," said Jack Murphy, current PLAT co-editor-in-chief, in his introductory remarks to Deamer's talk. He cautions, "Yet, for every emancipatory utopian path forward, an equally restrictive dystopian one exists."

Houston has avoided major upheaval so far --- the city and Uber tussled over background checks for drivers until the state preempted local ordinances --- but the sharing economy is having a transformative effect nonetheless. Even the defining force that shapes Houston’s built environment --- driving your own car and finding a place to park it --- is showing signs of giving way to the sharing economy. According to Pettitt, whose house is on a quiet neighborhood street, his guests use a combination of public transit, Uber, Lyft, and B-Cycle to get around Houston, and are now asking him about Toro (the Airbnb of car rental).

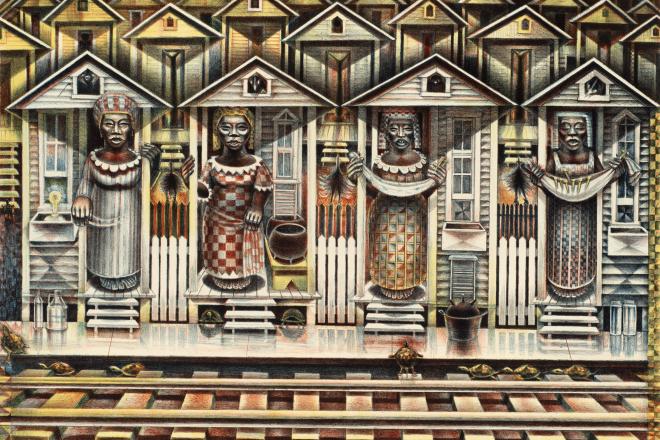

For young people saddled with debt, the sharing economy offers a way to afford living close to jobs, schools, and amenities inside Loop 610. To what extent, though, is the sharing economy about surviving? Is the free beer at WeWork a way to take the edge off the uncertainty of the gig economy? Are the little rooms packed with bunk beds in Pettitt’s Third Ward house no different than an old-school boarding house except that guests book their rooms by smartphone?

In the new issue of PLAT, a number of contributors explore whether the term "sharing economy" is a misnomer. In an interview with graduate student and PLAT 7.0 co-Editor-in-Chief Francis Aguillard, the London-based architect and architect Jack Self says, “Unfortunately, I think what has happened thus far is that it’s not really a sharing economy at all, it’s just the exploitation of latent value within existing commodities … [T]he rise of this fascination with sharing and with cooperative models of life is a highly pragmatic response when you have highly polarized wealth inequality in society.”

The tech sector is not only engaging in sharing at the scale of cars, houses, and office buildings but at the scale of whole cities. The highest-profile example at this urban scale is Amazon's process for locating its second headquarters. In a piece for PLAT, Ali Fard writes, "Cash-strapped cities wanting to compete with other global centers for jobs and development dollars give away billions in incentives just for the chance of having a tech giant land in their town."

Still, the sharing economy proceeds with fast-paced optimism. “I don’t think the sharing economy is just a response to inequality, it’s a better way of doing things,” says Pettitt.

Pettitt guides his guests to nearby businesses including Alchemy Candle Company, Doshi House, NuWaters Co-op, the Sunday Market on Navigation, and Crumbville, Texas. He participates in the Emancipation Economic Development Council, Third Ward is Home Civic Club, and the Greater Third Ward Super Neighborhood. He secured a small grant from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) to create maps of the Third Ward for the empty trailhead kiosks along the Columbia Tap trail.

“The money my guests are saving by not going to a big box hotel, they are spending it in the neighborhood,” says Pettitt. “Why extracting value? Why can’t the sharing economy not add value to a community?”

Pettitt’s questions are at the heart of this new issue of PLAT and the lecture series on Sharing organized by the editors in collaboration with Rice Design Alliance.

And what about rethinking the big box buildings themselves? Jack Self, while critical of the sharing economy, has also explored its positive potential. In his satirical and still optimistic proposal called the Ingot, a gold-coated highrise building for London would be built using the financing mechanisms developers use for luxury dwellings but would instead provide affordable housing designed from the ground up with shared facilities.

The new PLAT is packed with critical analyses of the sharing economy extracting value as well as earnest, real-life examples of sharing ownership as a way of adding value to communities instead. Amin Taha and Jason Coe of Groupwork talk with Sheila Mednick about the details of running an employee-owned architecture firm. Aron Chang and Alexandra Stokes recount how Dinner & Design at the Blue House, a shared work space and design collective in New Orleans, provides pro bono design services such as creating logos, posters, and websites.

All together, the issue and the lecture series respond to the new sharing economy by rethinking design from its economic underpinnings. In her foreword to PLAT, Rice Architecture Dean Sarah Whiting writes, "The time is ripe to return to a shared project --- a shared responsibility to channel Mister Rogers --- that can harness these changed economies and media toward a better collective future."

The new issue of PLAT is available for sale at platjournal.com. For more information on the Rice Design Alliance Fall 2018 lecture series, click here. The first lecture, featuring Yale professor Peggy Deamer, was Wednesday October 10, 7 pm at the MATCH. Jack Self, Director of the REAL Foundation, speaks Monday October 22, 7 pm, at the MATCH. John Alschuler, Chairman of HR&A Advisors Inc. will speak Monday October 29, 7 pm, at Farish Gallery, Anderson Hall, Rice University.