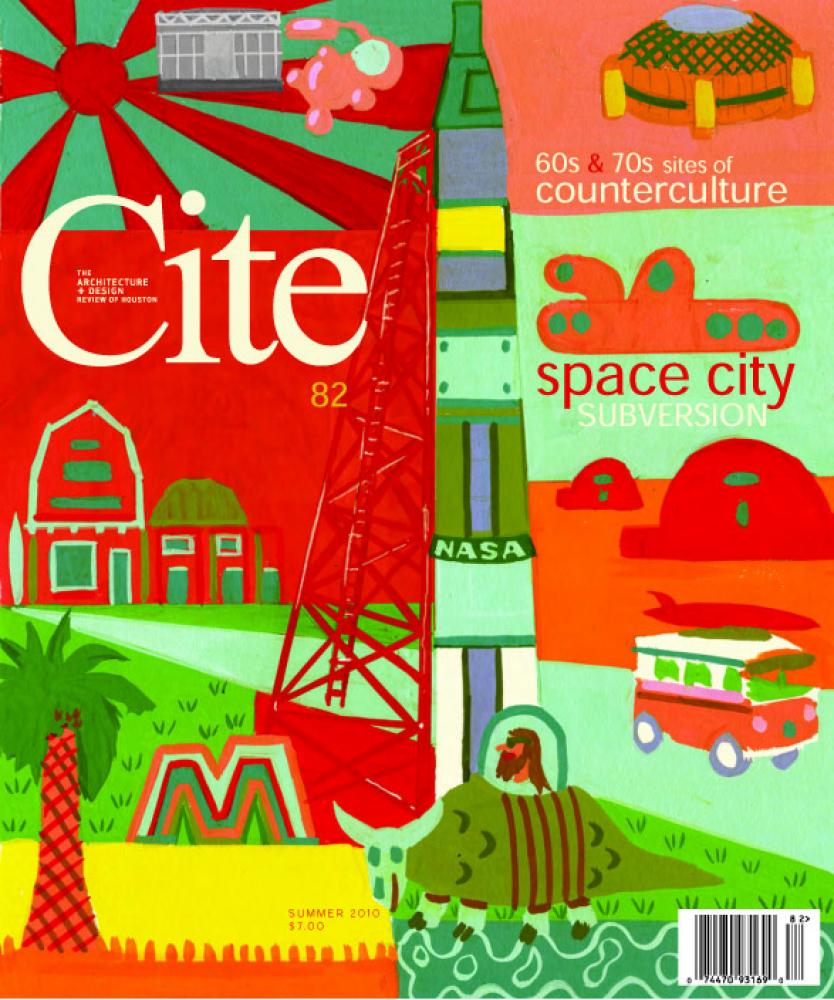

Cite 82: Counterculture

Summer 2010

Editor’s Note

By the time the Media Center at Rice University opened in February 1970 and Gunnar Birkerts silver-sided Contemporary Arts Museum hosted its first exhibit in 1972, the Aquarian generation had already gathered at Woodstock for a festival of peace and music. John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King were dead and the first public demonstrations against the Vietnam War had taken place in Washington. Both the center and the museum became prominent sites of Houston’s participation in the counterculture that was agitating America. They were the tip of the iceberg, temples for performing rituals of the avant-garde; but all around Houston there was a proliferation of places and activities that belonged to the “youthful opposition” that historian Theodore Roszak identified in “The Making of Counter Culture.”

Counterculture was never more than a small part of the total social-cultural scene, but it left an important legacy in Houston. Its vivid aberrancies stand out against a more uniform and grayish background of an America dominated by McCarthy-era investigations for “un-American activities” and Leave it to Beaver morality. In this issue of Cite we set out to examine not only the cultural implications of the counterculture itself but the sites in the city of Houston that it built, inhabited, or otherwise made use of.

America’s great countercultural era ran from the mid-1960s to the early ‘70s. It portrayed a society radically divided along generational lines, where youth openly rebelled against ingrained attitudes of the past, protesting the war in Vietnam and demanding equality for all races and genders as well as sexual liberation. It was not simply a political movement, but also created its own alternative subculture of wildly trippy music and art, graphic design, drugs, music, festivals, and communal living.

How did Houston participate in this new consciousness and lifestyle? Did the city have its own version of Haight-Ashbury, and was it Montrose or Market Square? Did the University of Houston–with its mandate to educate the working-class student provide alternative sites of learning that opened up new pedagogical opportunities? Did the university’s coexistence with the surrounding historically African-American Third Ward (and neighboring Texas Southern University) help shape a forum for radicalizing a disenchanted population of largely middle-class students? Did rethinking domestic architecture offer opportunities for designers and builders to subvert mainstream expectations of dwelling?

Houston in the 1960s and ’70s was a city of contradiction. The flower child generation and a group of homegrown social activists managed to proliferate within a culture of raw capitalism, conservative politics, and a deep belief in the myth of Houston as a “free enterprise city,” in Joe R. Feagin’s words. Profitable oil companies and nouveau riche entrepreneurs often shared a fascination with aspects of the counterculture and became its abetting angels, buying up the culture that mocked them. Increased reliance on the gas-guzzling automobile contributed significantly to shaping Houston’s future as the oil and gas capital of the country, and while the car brought freedom to many, it also went against the grain of the nascent environmentalist movement. The coming of NASA added a zap of futurism to the city’s culture, merging the astronaut with the cowboy—both captains of the frontier—in Houston’s psyche. A parade in Houston could often combine mounted trail riders with fl oats bearing rockets and astronauts, as well as (perhaps most metaphorical of all) a line of strange auto follies from the art car culture.

It didn’t always come together easily. Tensions were aggravated by a new attitude of cultural and social empowerment and aggressiveness. Reflecting confrontations that were sweeping across the country, young people in Houston led protests against the Vietnam war and supported social movements for civil, gay, and women’s rights. Normative society was bewildered and antagonized by the lifestyle, music, and stance of the counterculture with its rejection of Main Street values. Inevitably this free expression of beliefs and desires led to confrontations with authority and violent encounters between police and protesters.

Most of the sites discussed in this issue that put the Houston counterculture on the map in the 1960s and ’70s have either changed or been gentrified, but evidence of their character and influence can still be found throughout the city. While this era in American culture and society opened up new possibilities, it seems that today, with a few exceptions, the counterculture in Houston has been absorbed–or smothered–into the mainstream. With each step towards publication of this issue came another tip about a key counterculture site missed, and the realization that these sites were more ubiquitous than we had expected and had a major impact on aspects of Houston now taken for granted. We offer these scant pages, then, as a provocation to preserve records of, call attention to, celebrate, and critique the era.