Tei Carpenter leads Agency—Agency. Based in New York City, the design studio is at work on a range of projects that engage ideas of public space and material lifecycles. She won a 2021 League Prize from the Architectural League under the program’s theme of Housekeeping. In an interview related to the award, Carpenter spoke to some of her influences.

To date, the studio's largest built work remains the Big Brothers Big Sisters headquarters on Washington Avenue in Houston, a project Carpenter began while at Rice Architecture as a Wortham Fellow. Via email, she connected the dots between this important early project and the efforts that have followed in the years since. Could you briefly share the story of how you came to design the Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) headquarters in Houston? For interested readers, a detailed account was shared via an interview with Matt Johnson in Cite 97.

I had been in Houston teaching at Rice Architecture for about eight months as a Wortham Fellow when Pierce Bush reached out. At the time he was the Executive VP of the Houston Big Brothers Big Sisters, and since then he has become the CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters Lone Star. He and the organization wanted to develop a concept design and images for fundraising purposes. After a summer of working through intensive research and concept design phases with the BBBS staff and community members, we put together a few key ideas and images for the project. Not too long after that I learned that they wanted to move forward with the design and needed to develop construction documents. I didn’t anticipate that the project would come to fruition, and so quickly. This unexpected sequence launched my practice Agency—Agency in many ways.

What was the core architectural idea/problem of the BBBS project?

The organization had a very urgent and growing need to expand its services and increase its visibility to attract new mentors and volunteers and establish its identity in the city. It was previously located in a doctor’s office outside of the 610 freeway to the southwest and was quite introverted, both for staff members in separate spaces with little opportunity for collaboration and for the public. There wasn’t good access. We wanted to turn the program inside out by incorporating a number of public programs—like the three-story atrium, the cafe on the first floor, and the rentable event space with views to downtown on the third floor—to give the general public more reasons to engage with BBBS. How did the project fare during construction? What feedback have you received from users about the project?

The organization is super happy with the space and the project has been used in ways that I couldn’t have imagined, which excites me. Between Great Day Houston, which was filmed on the third floor every morning, to art workshops to proms, it’s become a space that has gone beyond the office type.

You were a Wortham Fellow at Rice Architecture from 2013–15. What was that experience like for you? What did it unlock for your work? How did it inform your trajectory afterwards?

It was valuable to have the platform and the time and space to do research and work. It’s a rare opportunity. Coming to Houston after growing up and living in New York City was a complete shock, but the city really grew on me. There’s a sense of casualness and openness that I really appreciate about Houston. When I was living there, it felt as though things were unfinished, that there was opportunity for exploration and experimentation especially in the arts. I think that openness, the sense that one could pursue projects directly with other people just by reaching out, is something that has informed other projects of mine since then. This optimism has become a method.

A big question, but what’s the relationship between academia and practice for you? Are they reinforcing or divergent forces?

I always think about it like a feedback loop that’s continually expanding and growing. Research in a studio might be informed by a current project I’m working on or an area of interest I’m developing in a project in the office. There’s feedback between the two and a spontaneity as to where that research trajectory goes and how it might be developed. Often the studio work and the sharing of ideas with students ends up, even laterally, having an impact on the studio’s work. It’s a cycle, but one that grows with time.

Beyond the local conditions of individual projects, what animates your work as an architect? Broadly, what are interested in using your agency to achieve?

I’m interested in thinking about how architecture can be transformative, especially as it relates to everyday experiences.

I’m particularly committed to thinking through architecture’s role within issues of climate justice. For example, in the Hamilton Gears Reuse Park in Toronto, we’ve been rethinking waste in a way that tries to incorporate a material narrative around construction, demolition waste, and reuse into the project.

More recently, I’ve been thinking about the everyday aesthetics of infrastructures. In particular, about how our experiences can shift with even very small interventions into everyday life like a commute or walking down the sidewalk. How can acts of design have possibilities for civic engagement even at intimate individual scales? This inspired the New Public Hydrant project, which takes advantage of the high quality of drinking water in New York City and transforms the fire hydrant into a drinking fountain and bottle fill station to provide fresh water to the public.

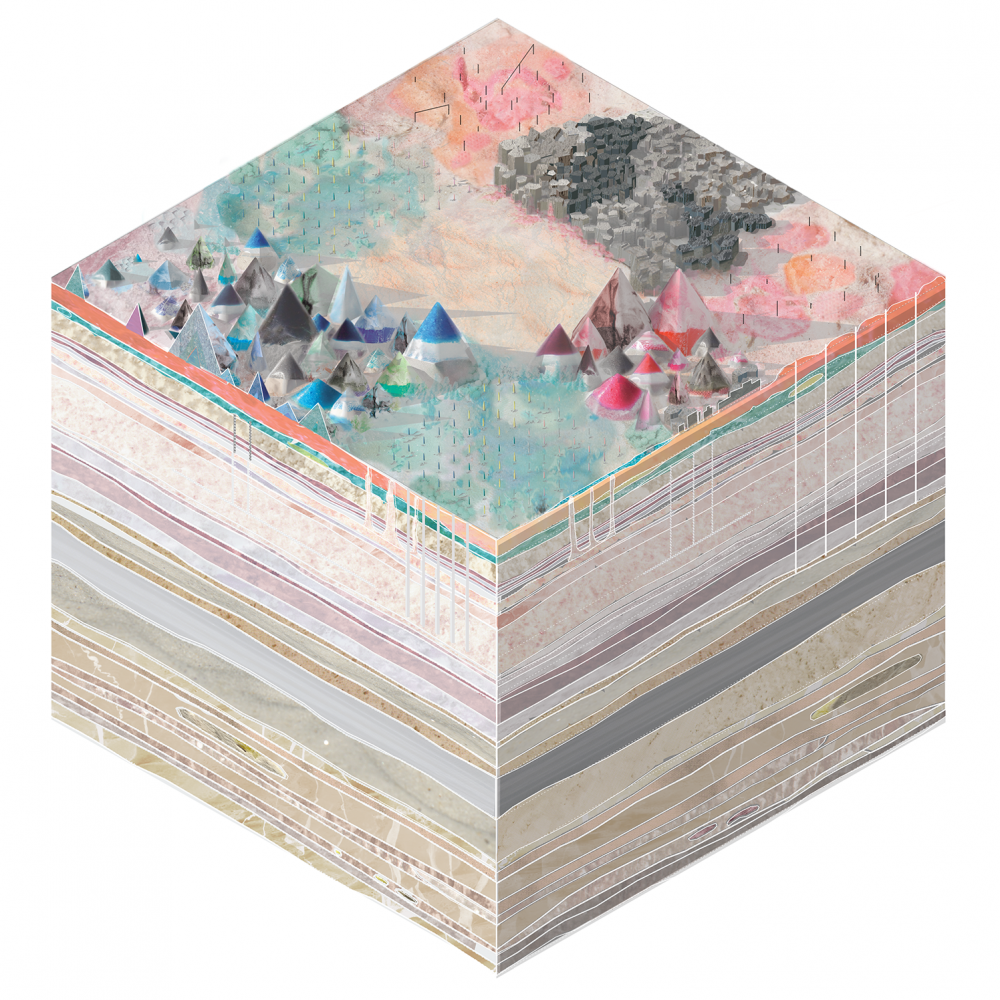

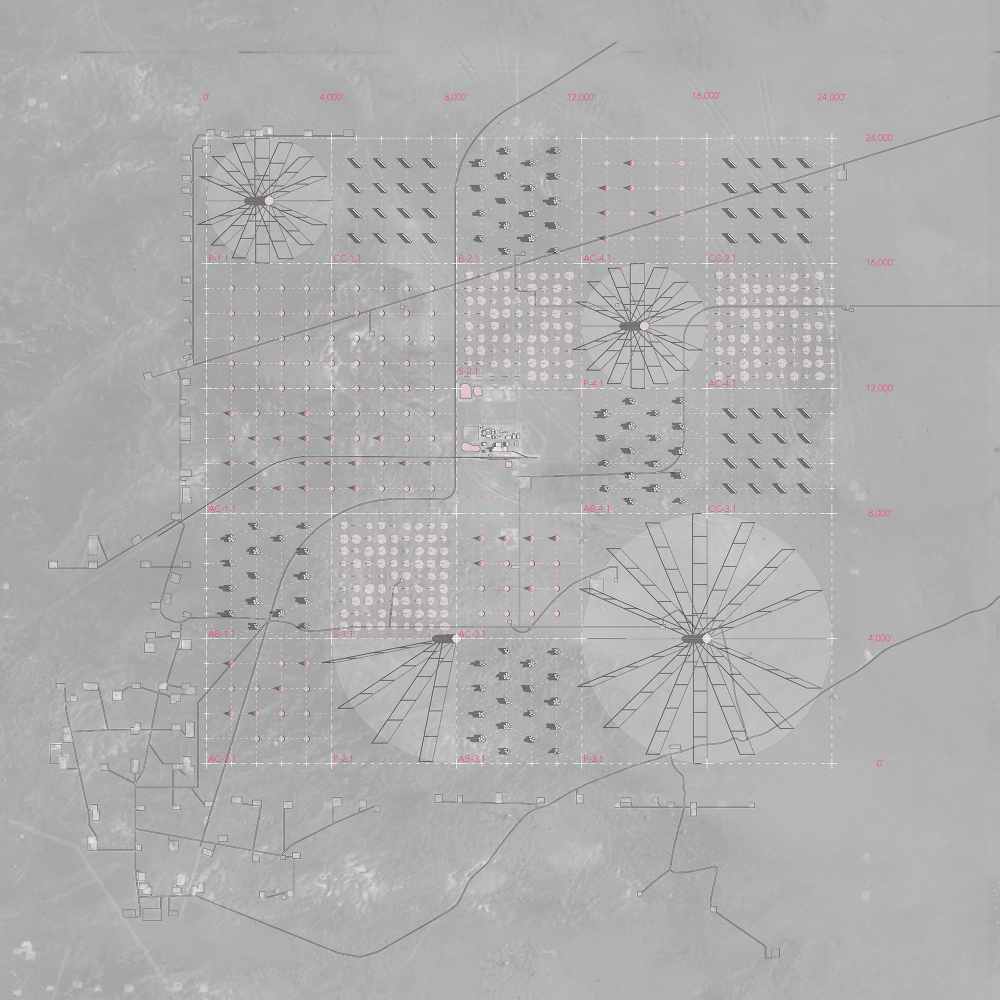

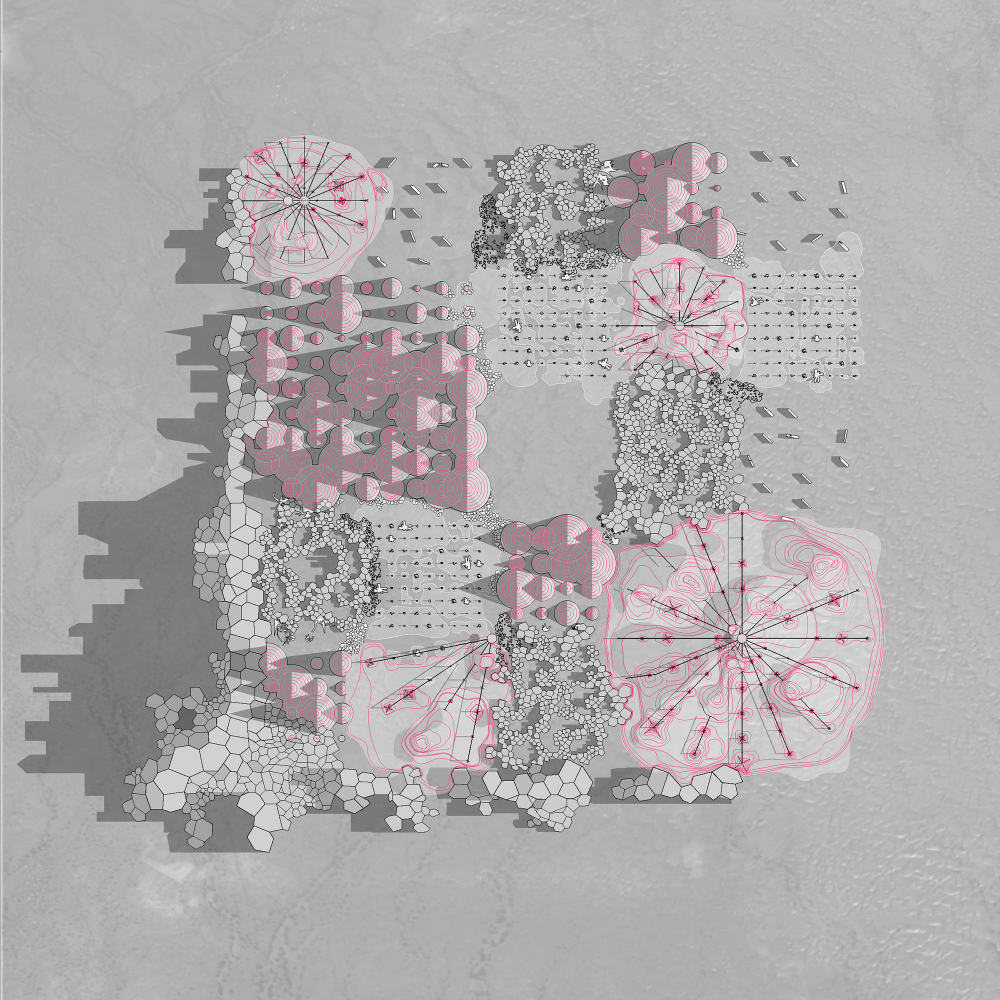

Some of your work, like Testbed or Pla-Kappa, investigates geologic or industrial processes. The imagery appears as these rainbow, mountainous shapes. Are you influenced by scientific/technical images? How do you relate forms of architectural image making to what is visually produced in the hard sciences?

I think it is less about the image itself and a style per se, but more about how to communicate processes tied to duration and geological time. For example, in both Testbed and Pla-Kappa, we looked towards at geological maps also core samples, with the goal of trying to describe the surface of the Earth together with the strata of Earth from the past and the future collapsed together. This also came out of a piece I wrote for Avery Shorts about looking at the moon. The idea that scientific/technical images are multidimensional is fascinating, yes, but at the same time we can’t always assume that scientific images are objective; they need to be read and understood in context.

Civic infrastructure is front and center in your work. The elements in projects like the New Public Hydrant or your Flatiron Crossings proposal are lively things; they have this dual existence between their expected safety functions and their deviations as accessible public services. How do you see the work of architects today as bound up in the topic of infrastructure?

This is a rich area for design thinking to expand the pragmatics and technical desires of infrastructure into both an aesthetic and social realm. It’s a powerful thought that that the design or redesign of infrastructure can also be an opportunity to speak to resource and material use or that infrastructure can even have an educational dimension. It’s also related to questions about climate that are so pressing.

Your presentation for The Architectural League’s League Prize this summer included a large model that brought together eight of your projects. There were a number of items set on the street in front of the façade of your Crown House. Could you share a bit about that residence in particular but also about the value of seeing these items in spatial dialogue with one another?

The Street Remodel 1:40 model was a way to collect a number of our projects into one scenographic streetscape—to see them all together, to imagine the city with both familiar and unfamiliar elements, and to build a relationship between our projects that had thus far existed separately. By doing this, we highlighted that they all have an urban expression and expand the idea that the street is a site of collectivity for both human and non-human actors.

By now we can see how systemic racism and climate change are related through the many struggles to realize environmental justice. How do you approach this topic in your teaching and in your work? How do you see the linkages between these two battles? How do you sort out what architects can do to meaningfully participate in these struggles?

I try to approach these topics head on as an educator. I just finished teaching an advanced design studio at Columbia GSAPP which collaborated with the Mastic Beach Conservancy and local stakeholders (including legislators and the former mayor of Mastic Beach, NY) to design an Ecology and Arts Center, which we referred to as a Beach Lab. The brief placed rising sea levels, climate migration, and spatial justice at the core of its concerns. It was important to remove the abstraction that can set in with these big topics and to make the issues real through a site and a specific community who directly worked with the students.

I think architects needs to start by questioning who is participating in the act of making architecture and asking who our work is for. I think sustained mentorship, which is something I learned from the Big Brothers Big Sisters project, helps to include more diverse voices and perspectives. This can help make change on the big issues you mentioned. In my own practice, I try to make space for mentorship, whether it’s through teaching or through platforms like Office Hours.

What’s upcoming for you and your work?

I’m busy with several projects. I’m wrapping up a few residential projects in upstate New York and just starting work on an exhibition design. It feels good to be doing research and jumping around in scale from the building to the body.

Tei Carpenter is Founder and Director of Agency—Agency, an award-winning design studio based in New York City. She was recently honored as a winner of the League Prize from the Architectural League of New York. Recently, she has taught at Columbia GSAPP, the University of Toronto, and Brown University.