Dazzling parks seem to open every few weeks in Houston, including the redesigned Levy and Emancipation parks, but by one important measure the city is failing to meet a basic standard of park access for about half of population.

As Gail Delaughter reports for Houston Public Media and Brian Reynolds writes for the Chronicle, Houston ranks 81st out of 100 major U.S. cities in the latest Parkscore report released by the Trust for Public Land (TPL).

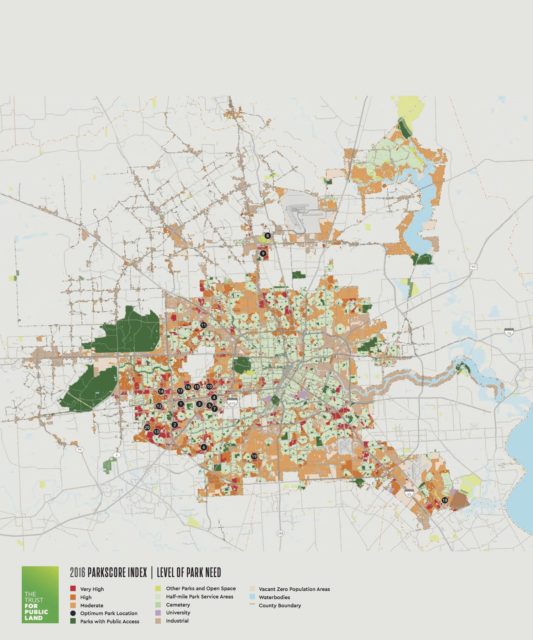

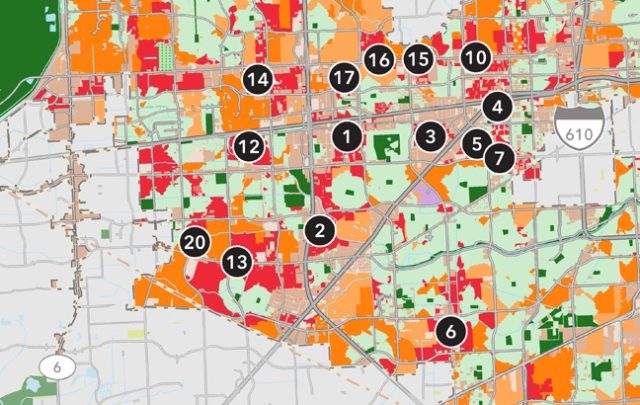

The Parkscore map for Houston shows parks and open spaces in dark green. Nearby areas within a 10-minute or half-mile walk are in light green. The orange and red spots are the park deserts — places where there is a density of people, especially children and low-income residents, but no park nearby.

“We based [our analysis] on actual walkability by working with park agencies to verify park access and calculate the 10-minute walk along streets,” says TPL data cruncher Bob Heuer. “If there is a railroad or highway that impedes access, you can have property adjacent to a park appear red because you cannot actually get to the park.”

Though this process of verification may seem obvious, so many interactive mapping tools do not take this step. “Most park equity studies measure distance as the crow flies,” notes Heuer.

Children across the bayou from Mason Park know the difference. Imagine the frustration of seeing that lush park barricaded by a set of railroad tracks, a four-lane thoroughfare with excessively spaced crosswalks, or even the bridgeless bayou itself. These park-adjacent park deserts show up on the map as kissing green and red blobs.

With funding from the Houston Endowment, the TPL piloted a tool that identifies where new park acquisition would have the greatest impact. Many are in the Gulfton, Sharpstown, and Alief neighborhoods where parks are limited and densities high. Public-private partnerships have vaulted Houston into the national spotlight by producing Discovery Green and Bayou Greenways, and remaking Buffalo Bayou Park, Hermann Park, Memorial Park, Levy Park, and others. Can this model address our park deserts?

With $5 million in grants from the Houston Endowment and Kinder Foundation, plus $450,000 from the city, an expansion of the SPARK School Parks program attempts to do just that. Founded in 1983 by Eleanor Tinsley, and led today by her daughter Kathleen Ownby, the SPARK program works with public schools to create publicly accessible parks. In exchange for financial investments to build on or upgrade their grounds, the schools agree to allow public access to the parks after hours and on weekends for neighborhood residents. SPARK has worked with over 200 schools in the Houston area. Today there are 150 active SPARK parks. The grants will fund 25 new SPARK parks and five “re-SPARKS” in designated park desert communities over the next three years.

In addition, the Powell Foundation has given $500,000 towards this initiative. To date 21 of the 25 new sites have been identified and schools are working on park designs. Three of the five re-SPARK projects have been identified and are in design. Clear Creek, Houston, Katy, Channelview, Alief, Fort Bend, Pasadena, and Aldine independent school districts, as well as several charter schools, are participating. In addition to the foundation support, funds are coming from individual schools, school districts, management districts, MUD districts, county commissioners, home owner’s associations, private sector, and City of Houston Community Development Block Grant funds.

In the past, the program has relied on the initiative and fundraising support of communities surrounding the schools, a method that works in well-off areas. For example, a lovely re-SPARK recently opened at Roberts Elementary near Rice University. The one at Travis Elementary in Woodland Heights features a dinosaur sculpture designed by Paul Kittelson. But the Houston Endowment and Kinder grants refocus the SPARK program on the park deserts identified in the TPL map. Plus, the City of Houston’s cash-starved Parks and Recreation Department pinned its 2015 master plan to the map. Cost-effective, bite-sized, and high-impact — the SPARK expansion is a smart idea that will produce quick results where it matters most.

Bush Elementary SPARK Park in Alief will be under construction this summer with a dedication planned for November 2017. Although the apartment complexes near the school are close to a massive detention basin and park along Brays Bayou, the Sam Houston Tollway blocks pedestrian access. The new SPARK at Bush Elementary will provide a walkable neighborhood park to everyone who lives nearby.

As the city puzzles through the broad directives of Plan Houston, perhaps the Planning, Parks, and Public Works department heads can also look at those kissing blobs and dream up safe infrastructure that connects more kids to parks and schools. A footbridge or tunnel here, a mid-block crossing or High-intensity Activated crossWalK (HAWK) signal there, could go a long way.

The TPL map suggests even more. It is perhaps our best metric of walkability. Again, the process of verifying on-the-ground conditions sets it apart. Tools like Walk Score and Google’s “Areas of Interest” are so focused on measurable densities of storefronts that they relegate much of Houston to the not-interesting dustbin. The TPL map steers clear of walkability-as-shopability. Park access is a more universalizable goal than trying to build four-story apartment blocks atop ground-floor retail all over the city.

The love of parks seems to cross all political and demographic boundaries in Houston. For example, the continued support for a bridge across the bayou in Mason Park in the face of a $1.4 million cost overrun demonstrates the political will to better connections within the bayou park system. The successful bond measure in 2012 to provide public funds to the Bayou Greenways effort also shows this broad base of support for parks.

Can that love cross the boundaries of the park itself? Is it possible for park-love to seep into the redesign of adjacent streets? The implementation of the new Bike Plan, if pursued as part of a comprehensive strategy that improves conditions for those walking, riding transit, and rolling in wheelchairs, could improve the Parkscore as well. Perhaps this park map can turn Houston’s attention, finally, to urban design.

Raj Mankad is editor of Cite, a publication of the Rice Design Alliance. An earlier version of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2016 issue.