This article by Raj Mankad was originally published by The Dirt on March 21, 2017. Follow Rice Design Alliance's publications and events about living in floodplains at #H2Ouston and #SyntheticNature.

San Antonio’s historic downtown is the main draw for a tourism industry with a $13 billion impact. The history is about as thick as it gets for a U.S. city, but its commodification has taken a toll. For example, just up the steps from the Rainforest Café on the Riverwalk, the Alamo faces off with Ripley’s Believe It or Not and Madame Toussaud’s Waxworks. Follow the San Antonio river downstream for eight miles, though, and you encounter modest, centuries-old missions in serene, almost rural settings. And if you follow the river three miles upstream, you find Brackenridge Park, a hard-working 343-acre city park packed with locals.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) held its third Leading with Landscape conference in San Antonio, and, unlike the first two iterations of the series in Toronto and Houston, the event focused on a single site — Brackenridge Park. Landscape architects and local leaders, including Mayor Ivy Taylor, focused on the park itself or presented examples relevant to the discussion of its past and future. More than 400 attendees were drawn to the Pearl Stable, a brick barn built in 1894 and converted to a theater.

Brackenridge Park planning process. Parks and Recreation San Antonio and City of San Antonio Transportation and Capital Improvements Workshop.

Brackenridge Park planning process. Parks and Recreation San Antonio and City of San Antonio Transportation and Capital Improvements Workshop.

Lynn Osborne Bobbit, executive director of the Brackenridge Park Conservancy, opened the conference by announcing the approval of a master plan for the park that was commissioned by the city and crafted by Rialto Studio. The first draft of the master plan faced stiff resistance around parking changes, the closing of interior roads, and fears that working-class people of color would lose access. This controversy was not discussed in detail during the conference, but was alluded to by City Council member Robert C. Treviño and others.

Charles Birnbaum, FASLA, president and founder of TCLF, framed the conversation at the conference start. He said Brackenridge Park has not received the national attention it merits because it was not designed by a master. Frederick Law Olmsted did visit the site in 1857 before it became a park and wrote that the clear springs there that give rise to the San Antonio River “may be classed as the first water among the gems of the natural world.” After Olmsted’s visit, in the late nineteenth century, a private company pumped water uphill and out to the burgeoning city. When this system became obsolete, the owner, George Washington Brackenridge, donated the site, which accumulated uses piecemeal, like the zoo and Witte Museum. Informal uses, like Easter weekend camping, developed along the riverbanks as well.

The history goes much deeper, at least 11,000 years, as several speakers noted. Visitors have had the opportunity to observe archaeological digs unveiling ancient artifacts in the vicinity of the bike trails, zoo, Japanese Garden, natural history museum, playgrounds, cafes, pavilions, picnic tables, and parking lots.

Leading landscape architects had visited the park prior to the conference and carefully situated Brackenridge in a national context. Chris Reed, FASLA, founder of Stoss Landscape Urbanism, gave an overview of major projects around the country showing the resurgence of landscape design not just in the making of parks but in the shaping of cities. Gina Ford, ASLA, a principal and landscape architect in Sasaki’s Urban Studio, talked about how park edges matter, citing examples in New York and Houston to both define park edges and make them more porous. Brackenridge’s edge comes in and out of focus, making its extent hard to understand.

Bob Harris, a partner at Lake|Flato Architects, spoke about plans for Confluence Park, where San Pedro Creek meets the San Antonio River near Mission Concepción. He noted the door-to-door outreach campaign that gained acceptance from an initially-skeptical neighboring community. A former industrial yard will be transformed into a park with a pavilion of massive concrete forms. In a similar vein, Kinder Baumgardner, ASLA, managing partner of SWA’s Houston office, gave an account of how difficult it can be to reconcile the varied demands of neighboring and regional park users.

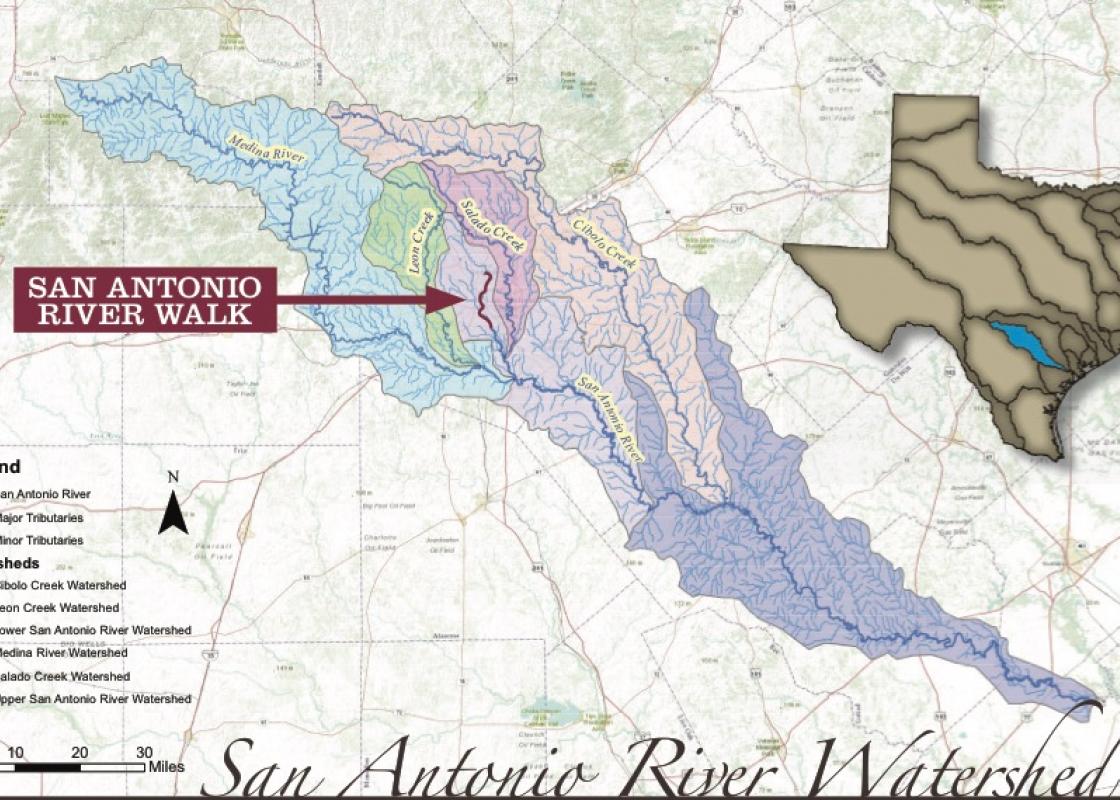

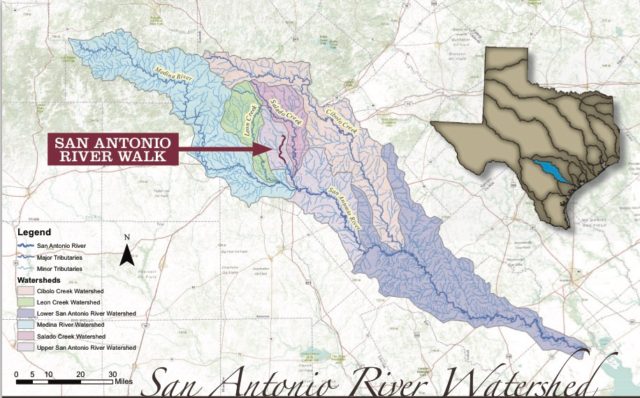

Suzanne B. Scott, general manager of the San Antonio River Authority, talked about the decades-long effort it took to piece together land, permits, funding, community buy-in, and political support to create a continuous trail system stretching from the “Mission Reach” in the south, through downtown, to the conference site in the “Museum Reach,” which, with an awkward dogleg at US 281, ends at Brackenridge Park. The authority has expanded its vision to include creeks and key streets like the Broadway Cultural Corridor. David Adjaye’s design for the Pace Foundation expresses this ambition beautifully along San Pedro Creek.

Christine Ten Eyck, FASLA, shared her firm’s designs for a new entry sequence — a lush canyon of dripping vines — for the San Antonio Botanical Gardens adjacent to Brackenridge.

Doug Reed, FASLA, spoke about connection to community and a yearning for permanence, about emotion and deep time. Using maps and diagrams, he showed how Brackenridge is fragmented now, but has the potential to bring all these elements we yearn for together. He said Brackenridge does not fit neatly into any one park model and it may in fact be more like a national park than any city park.

The comparison to a national park echoed a point Birnbaum made at the start of the conference: Brackenridge Park should be part of a national heritage area that includes the missions and is connected by a narrative around water. The recent designation of the missions as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, he argues, missed an opportunity to raise the profile of the broader landscape and tell a story around the river.

How, though, can Brackenridge Park be elevated as a national landmark without losing the authenticity that comes out of its “plop-and-drop” accumulation of uses? One recurring response from speakers was made very clearly by Vincent Michael, executive director of the San Antonio Conservation Society, who said the modern view of preservation is “process and community” more than restoring design integrity. The term “community,” as Baumgardner showed, is difficult to pin down. As for process, landscape architects often endure extended criticism as they try to resolve different demands by layering uses.

A May 6 bond vote that would provide $21.5 million for Brackenridge Park will be a critical test of whether the newly-adopted master plan and heightened ambitions engendered by TCLF’s conference have been enough to move the process forward.

Further Reading

Cook-Monroe. “Could Brackenridge Park Become a National Heritage Area?” Rivard Report. March 4, 2017.

Dimmick, Iris. “Brackenridge Park’s ‘Intervention’ Brings Hundreds of Minds to the Table.” Rivard Report. March 4, 2017.