Thomas McNeely's new novel, Ghost Horse (2014, Gival Press, 246 pages) is set in Houston in the 1970s. Not coincidentally, it's a difficult book to read. The characters lead difficult lives, some broken by divorce and others shadowed by fear, child abuse, domestic violence. The lines between race and class are sharply drawn and harshly spoken; the novel turns when the main character, Buddy, a young boy whose parents are separated, plays a cruel prank on a friend and spits a racial epithet at him.

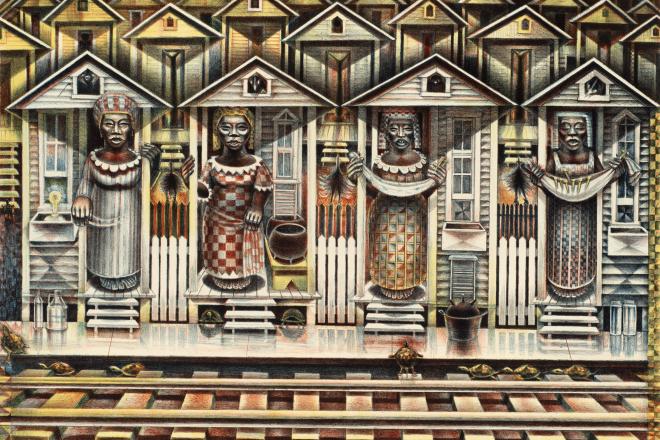

Much of the action takes place in the car, as Buddy, the novel's main character, is shuttled back and forth between a private school where he struggles to make friends and his mother's house near Telephone Road. As good as McNeely is at bringing Buddy's confusion and frustration to life, as the boy tries to figure out whether he ought to align himself with his father, or mother, or both, or neither, he is even better at capturing the ambiguity of Houston's built environment, especially in the neighborhoods near Telephone: "All the way back to his mother's house," McNeely writes, "past El Destino Club #2, where purple lights revolve, and Tellepsen Tool, where sparks shower night and day, and Andrew Jackson Grammar School's cement playground, enclosed in a barbed-wire fence; past the orange duplexes at the end of his mother's street, whose porch roofs sag like heavy-lidded eyes, where Mexican children stare at his father's car, then vanish into the houses, or around corners, or under gutted cars."

Descriptions like that, creating an unsettling setting that engulfs the characters, pop up every few pages. Or like this: "In the distance is the Astrodome, an ancient, enormous UFO, and between them and it, in the yellowish haze, endless blocks of apartment complexes, convenience stores, mini-malls."

Or like this: "They cross a wide, curving road that follows the curve of the bayou, where teenagers race cars. On the side of the road opposite the bayou is a shadowy park, where no one goes, even in daytime, and past it, the row of shacks where the poor whites lived. When they walked home [...], they stayed on the side of the road where they were now, away from the park and the whites' barking dogs."

Clearly, the novel doesn't glamorize Houston; it's represented as a divided city, where the distribution of wealth --- and, correspondingly, land use, is uneven, unpredictable. As McNeely explains in an interview with The Rumpus:

The Houston of the ['70s], at least as it exists in my memory, was a much wilder place than the Houston of today. There was a lot more country to it. The social divisions between whites and African-Americans were very rigid, as they still are. One factor that upset this rigid division was the emergence of a Latino middle class that started to move into white neighborhoods. The Joe Campos Torres case, which is referenced in the book, was an intersection of this country lawlessness and the growing economic and political power of the Latino middle class.

The novel is worth reading to get a sense of this history.

Recently, McNeely retraced his steps along Telephone Road, which remains a wild place, to borrow his phrase, at least in comparison with other close-in neighborhoods that are rapidly gentrifying, and which management districts and tax increment reinvestment zones haven't yet touched. This is what he saw:

More >>>

Read an interview with McNeely at Lone Star Literary Life

by Allyn West